From Presidio to Post: Recent Archaeological Discoveries Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encountering Nicaragua

Encountering Nicaragua United States Marines Occupying Nicaragua, 1927-1933 Christian Laupsa MA Thesis in History Department of Archeology, Conservation, and History UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2011 ii Encountering Nicaragua United States Marines Occupying Nicaragua, 1927-1933 Christian Laupsa MA Thesis in History Department of Archeology, Conservation, and History University of Oslo Spring 2011 iii iv Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................... v Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... viii 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Topic .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Research Questions ............................................................................................................................. 3 Delimitations ....................................................................................................................................... 3 The United States Marine Corps: a very brief history ......................................................................... 4 Historiography .................................................................................................................................... -

Alaska Beyond Magazine

The Past is Present Standing atop a sandstone hill in Cabrillo National Monument on the Point Loma Peninsula, west of downtown San Diego, I breathe in salty ocean air. I watch frothy waves roaring onto shore, and look down at tide pool areas harboring creatures such as tan-and- white owl limpets, green sea anemones and pink nudi- branchs. Perhaps these same species were viewed by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542 when, as an explorer for Spain, he came ashore on the peninsula, making him the first person from a European ocean expedition to step onto what became the state of California. Cabrillo’s landing set the stage for additional Span- ish exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries, followed in the 18th century by Spanish settlement. When I gaze inland from Cabrillo National Monument, I can see a vast range of traditional Native Kumeyaay lands, in- cluding the hilly area above the San Diego River where, in 1769, an expedition from New Spain (Mexico), led by Franciscan priest Junípero Serra and military officer Gaspar de Portolá, founded a fort and mission. Their establishment of the settlement 250 years ago has been called the moment that modern San Diego was born. It also is believed to represent the first permanent European settlement in the part of North America that is now California. As San Diego commemorates the 250th anniversary of the Spanish settlement, this is an opportune time 122 ALASKA BEYOND APRIL 2019 THE 250TH ANNIVERSARY OF EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT IN SAN DIEGO IS A GREAT TIME TO EXPLORE SITES THAT HELP TELL THE STORY OF THE AREA’S DEVELOPMENT by MATTHEW J. -

COURSE LEGEND L M T T G a N a a a a N H M a W Dr Ct H W a V 274 N R O E U Tol V I V O a P a a a D Ac E H If E Y I V V Ca E D D R E Ur St G Beadnell Way Armo a R F E

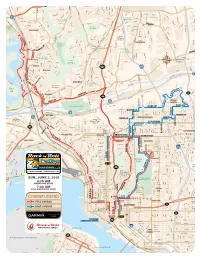

C a r d y a e Ca n n W n S o o in g n t r D i to D n S r n L c t o i u D e n c S n ate K n o r e g R a G i e l ow d l c g s A e C e id r v e w S v l e Co R e e f n mplex Dr d v a e a v l h B e l l ld t s A h o C J Triana S B a a A e t A e S J y d nt a s i a e t m v e gu e L r S h a s e e e R Ave b e t Lightwave d A A v L t z v a e M v D l A sa Ruffin Ct M j e n o r t SUN., JUNE 2, 2013 B r n e d n o Mt L e u a a M n r P b r D m s l a p l D re e a A y V i r r h r la tt r i C a t n Printwood Way i M e y r e d D D S C t r M v n a w I n C a d o C k Vickers St e 6:15 AM a o l l e Berwick Dr O r g c n t w m a e h i K i n u ir L i d r e i l a Engineer Rd J opi Pl d Cl a n H W r b c g a t i Olive Spectrum Center MARATHON STy ART m y e e Blvd r r e Ariane Dr a y o u o D u D l S A n L St Cardin Buckingham Dr s e a D h a y v s r a Grove R Soledad Rd P e n e R d r t P Mt Harris Dr d Opportunity Rd t W a Dr Castleton Dr t K r d V o e R b S i F a l a c 7:00 AM e l m Park e m e l w a Mt Gaywas Dr l P o a f l h a e D S l C o e o n HALF-MARATHON START t o t P r o r n u R n D p i i Te ta r ch Way o A s P B r Dagget St e alb B d v A MT oa t D o e v Mt Frissell Dr Arm rs 163 e u TIERRASANTA BLVD R e e s D h v v r n A A Etna r ser t t a our Av S y r B A AVE LBO C e i r e A r lla Dr r n o M b B i a J Q e e r Park C C L e h C o u S H a o te G M r Orleck St lga a t i C t r a t H n l t g B a p i S t E A S o COURSE LEGEND l M t t g a n a a a a n H a w M Dr Ct h w A v 274 n r o e u Tol v i v o a P A A a D ac e h if e y ica v v e D D r e ur St g Beadnell Way Armo -

Colonial Spanish Terms Compilation

COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS COMPILATION Of COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS And DOCUMENT RELATED PHRASES COMPILATION Of COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS file:///C|/...20Grant%202013/Articles%20&%20Publications/Spanish%20Colonial%20Glossary/COLONIAL%20SPANISH%20TERMS.htm[5/15/2013 6:54:54 PM] COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS And DOCUMENT RELATED PHRASES Second edition, 1998 Compiled and edited by: Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Navarro Wold Copyright, 1998 Published by: SHHAR PRESS, 1998 (Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research) P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 1-714-894-8161 Cover: Census Bookcover was provided by Ophelia Marquez . In 1791, and again in 1792, a census was ordered throughout the viceroyalty by Viceroy Conde de Revillagigedo. The actual returns came in during 1791 - 1794. PREFACE This pamphlet has been compiled in response to the need for a handy, lightweight dictionary of Colonial terms to use while reading documents. This is a supplement to the first edition with additional words and phrases included. Refer to pages 57 and 58 for the most commonly used phrases in baptismal, marriage, burial and testament documents. Acknowledgement Ophelia and Lillian want to record their gratitude to Nadine M. Vasquez for her encouraging suggestions and for sharing her expertise with us. Muy EstimadoS PrimoS, In your hands you hold the results of an exhaustive search and compilation of historical terms of Hispanic researchers. Sensing the need, Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Wold scanned hundreds of books and glossaries looking for the most correct interpretation of words, titles, and phrases which they encountered in their researching activities. Many times words had several meanings. -

Presidio Visitor

THE PRESIDIO presidio.gov TRANSPORTATION Golden Gate Bridge PRESIDIGO SHUTTLE PUBLIC TRANSITDigital Terrian Mode Hillshadel (DTM_3FT.tif) - The DTM represents Fort Point he free PresidiGo Shuttle Three Muni busground routes currentlyelevations. serve This DTM is not National Historic Site Shuttle Routes Tis a great way to get to and the Presidio (withhydroflattened more coming soon): or hydroenforced. PACIFIC 2 PRESIDIO HILLS Route, Stop ID, + Direction stops at the Golden Gate 101 around the park. It has two routes. OCEAN SAN FRANCISCO BAY 28 DOWNTOWN Route + Stop ID PresidiGo Downtown provides Bridge Welcome Center 1 Torpedo Wharf Muni+ Golden Gate Transit service to and from key transit 29 stops at Baker Beach Golden Gate Bridge connections in San Francisco. N Welcome Center 30 Muni Lines and ID Numbers stops at Sports Basement 0 500 FT 1,000 FT Warming Hut Muni Stops Presidio Hills connects to 25 30 28 at Crissy Field 0 250 M Transfer Point for Muni or Golden Gate Transit Battery destinations within the park. East Vista Nearby Muni service: West Bluff West Bluff Picnic Area DOWNTOWN Route A Trail for Everyone (see reverse for information) East Beach 1 33 43 44 45 Coast Guard Pier Transit Center, the Letterman Length: 2.7 miles (4.3 km) Digital Arts Center, Van Ness Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail 28 Coastal Greater Farallones National Avenue and Union Street, Length: 2.7 miles (4.3 km) Batteries Marine Sanctuary BICYCLING Golden Gate Promenade / Bay Trail Length: 4.3 miles (6.9 km) Marina Embarcadero BART, and the Gate Marina District, Golden Crissy Marsh 30 Fort Mason, California Coastal Trail Gate 28 Crissy Field Salesforce Transit Center. -

Presidio Coastal Trail Cultural Resource Survey

Presidio Coastal Trail Cultural Resource Survey Background This survey was prepared at the request of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy to provide information on known and possible cultural resources along the Fort Scott bluffs in preparation for the design of the Presidio Coastal Trail. This trail will be a link in the statewide California Coastal Trail. The California Coastal Conservancy oversees the statewide implementation efforts for developing the Coastal Trail, and provides this definition of the trail: “A continuous public right-of-way along the California Coastline; a trail designated to foster appreciation and stewardship of the scenic and natural resources of the coast through hiking and other complementary modes of non-motorized transportation.” (California Coastal Conservancy, 2001.) A “Presidio Trails and Bikeways Master Plan and Environmental Assessment” (aka “Trails Master Plan”) was developed jointly by the National Park Service and the Presidio Trust for that section of the Coastal Trail running through the Presidio of San Francisco, and was adopted through a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) in July 2003. The Trails Master Plan identified improvements needed to the California Coastal Trail in order to upgrade the existing route to a multi-use trail with associated bicycle lanes on Lincoln Boulevard and supporting components, such as trailheads and overlooks. This 3 mile Presidio trail section travels generally along the coastal bluffs, following Lincoln Boulevard. 1 The areas west and south of the Golden Gate Bridge/Highway 101 are known to have been the sites of important cultural activities over the past 200 years associated with the military and civilian histories of the Presidio of San Francisco. -

Presidio and Pueblo: Material Evidence of Women in the Pimería

Presidio and Pueblo: Material Evidence of Women in the Pimeria Alta, 1750-1800 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Waugh, Rebecca Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 10:54:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195118 PRESIDIO AND PUEBLO: MATERIAL EVIDENCE OF WOMEN IN THE PIMERÍA ALTA, 1750–1800 by Rebecca Jo Waugh Copyright © Rebecca Jo Waugh 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2005 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Rebecca Jo Waugh entitled Presidio and Pueblo: Material Evidence of Women in the Pimería Alta, 1750– 1800 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4 May 2005 Dr. J. Jefferson Reid, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4 May 2005 Dr. Teresita Majewski, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4 May 2005 Dr. Thomas E. Sheridan, Ph.D. Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Chapter 2: Exploring the Americas, 1400-1625

Exploring the Americas 1400–1625 Why It Matters Although the English have been the major influence on United States history, they are only part of the story. Beginning with Native Americans and continuing through time, people from many cultures came to the Americas. The Impact Today The Americas today consist of people from cultures around the globe. Native Americans, Spanish, Africans, and others discussed in Chapter 2 have all played key roles in shaping the culture we now call American. The American Republic to 1877 Video The chapter 2 video, “Exploring the Americas,” presents the challenges faced by European explorers, and discusses the reasons they came to the Americas. 1513 • Balboa crosses the Isthmus of Panama 1492 1497 • Christopher Columbus • John Cabot sails to reaches America Newfoundland 1400 1450 1500 1429 c. 1456 • Joan of Arc defeats c. 1500 • Johannes Gutenberg the English at French • Songhai Empire rises in Africa uses movable metal town of Orléans • Rome becomes a major center type in printing of Renaissance culture 36 CHAPTER 2 Exploring the Americas Evaluating Information Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you learn about European exploration of the Americas. Step 1 Fold the paper from the top right corner down so the edges line up. Cut off the leftover piece. Fold a triangle. Cut off the extra edge. Step 2 Fold the triangle in half. Unfold. The folds will form an X dividing four equal sections. Step 3 Cut up one fold line and stop at the middle. Draw an X on one tab and label the other three. -

Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas

Volume 1997 Article 6 1997 Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas Anne A. Fox Center for Archaeological Research Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Fox, Anne A. (1997) "Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 1997, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.21112/ita.1997.1.6 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1997/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1997/iss1/6 Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas Anne A. Fox with a contribution by Barbara A. -

POINTS of SCENIC INTEREST Been the Headquarters for American M Ilitary Commands Defending the Territory W Est of the Rocky Mountains S I Nce 1857

T hroughout the Presidio are marke r s indicating points of histori cal interest, such as the one l ocating the Old Indian B urial Ground~, situat ed in front of Buildi ng 103 on Montgomery Street, and another a t the j unction of Ruger Street and Lincoln Boulevard near the Lombard Street entrance, which reads , "On the hillside south of this point and in the area i mmediately t o the north was loc.ated Camp M e rriam. The 1st and 7th California, 5 lst Iowa, 1st Idaho, 20th Kansas , 1st New York and 1s t South Dakot a Volunteer Regiments of Infantry and other unit s which partic ipated in the war w ith Spain were quartered in this camp. 11 Standing on the high hills of the Presidio, one gets a spectacular OF SAN view in every direction. T o the southeast, one can look down on the City of San Francisco; t o the west, the flag flying above F ort Miley ca:i be s een, and beyond, the Pacifi c Ocean with 'the Farallo n Islands fa r Ul the distance; t o the nor thwest across the Golden Gate are F o rt Barry a....! F ort Cronkhite, where batte ries of fast-firing missiles a r e pois ed and ready to repel a sudde n a ir attack by an en e my. To the north is F ort Baker, h o m e of the 6th Region, U. S. Army Air Defens e Command; to t he northeast across the bay is Angel Island; slightly t o the east of ~I I s land is Alcatr a z I sland, formerly a U. -

Presidio Interpretive Plan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Presidio of San Francisco Golden Gate National Recreation Area Interpretive Plan Presidio of San Francisco EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA™ 1 1 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Presidio of San Francisco Golden Gate National Recreation Area Interpretive Plan Presidio of San Francisco EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA™ 1 1 Appendix D: Authors Photo Courtesy • Kirke Wrench • Alison Taggart-Barone • Frank Schmidt • Tung Chee • Ingrid Bellack • George “Doc” Miles • Mel Mashman • Dan Ng “The Presidio of San Francisco! The name itself bespeaks unusual scenery and atmosphere. And it has all of that…On the very tip of the peninsula there sits the ‘god of war’ with his mailed feet astride the Golden Gate. He is not an angry god, however, because he has his being in one of the most wonderful settings of a benignant nature that can be found anywhere. An emerald clothed land and sapphire sea warm and sparkling in a golden sun conspire to make the frowning ‘Lord of Battles’ lay aside his grim weapons and joyfully revel in all the beauty about him.” —San Francisco Chronicle January 16, 1927 621 Appendix D: Authors Photo Courtesy • Kirke Wrench • Alison Taggart-Barone • Frank Schmidt • Tung Chee • Ingrid Bellack • George “Doc” Miles • Mel Mashman • Dan Ng 62 1 Appendix C: List of Contributing Documents & Contributors Appendix D: Authors THE PRESIDIO contains a multi-layered story of people, culture, and landscape. Situated in a dynamicBackground and diverse documents region, it reflectsand contributions millennia toof thishuman interpretive activity from plan pre-European Special thanks to the Presidio Trust and Golden Gate Parks peoples to include:the present occupants. -

Obras De Don Pio Bolaños. Introducción Y Notas De Franco Cerutti

OBRAS DE DON PIO BOLAÑOS INTRODUCCION Y NOTAS DE FRANCO CERUTTI PIS% couccsotcueruim SERIE CIENCIAS HUMANAS NQ 2 DERECHOS RESERVADOS POR EL FONDO DE PROMOCION CULTURAL — RAMO DE AMERICA — 1976 Impresos ea les talleres de Papelera Industrial de Nicaragua, S. A. — (MUY. FONDO DE PROMOCION CULTURAL BANCO DE AMERICA La Junta Directiva del Banco de América, consciente de la impor- tancia de impulsar los valores de la cultura nicaragüense, aprobó la creación de un Fondo de Promoción Cultural que funcionará de acuer- do a los siguientes lineamientos. 1.— El Fondo tendrá como objetivo mediato la promoción y desarrollo de los valores culturales de Nicaragua; y 2.— El Fondo tendrá como objetivo inmediato la formación de una colección de obras de carácter histórico, litera- rio, arqueológico y de cualquier naturaleza, siempre que contribuyan a enriquecer el patrimonio cultural de la nación. La colección patrocinada por el Fondo se denominará oficialmente como "Colección Cultural- Banco de América". El Fondo de Promoción Cultural, para desempeñar sus funciones, estará formado por un Consejo Asesor y por un Secretario. El Con- sejo Asesor se dedicará a establecer y a vigilar el cumplimiento de las políticas directivas y operativas del Fondo. El Secretario llevará al campo de las realizaciones las decisiones emanadas del Consejo Asesor. El Consejo Asesor del Fondo de Promoción Cultural está integrado por: Dr. Alejandro Bolaños Geyer Don José Coronel Urtecho Dr. Ernesto Cruz Don Pablo Antonio Cuadra Dr. Ernesto Fernández Holmann Dr. Jaime Incer Barquero Don Orlando Cuadra Downing, Secretario OBRAS PUBLICADAS POR EL FONDO DE PROMOCION CULTURAL DEL BANCO DE AMERICA: SERIE: ESTUDIOS AROUEOLOGICOS 1 Nicaraguan Antiquities por Carl Bovallius (Edición ,Bilingüe) 2 Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Nicaragua por J.