The Impact of Car Share Services in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United-2016-2021.Pdf

27010_Contract_JCBA-FA_v10-cover.pdf 1 4/5/17 7:41 AM 2016 – 2021 Flight Attendant Agreement Association of Flight Attendants – CWA 27010_Contract_JCBA-FA_v10-cover.indd170326_L01_CRV.indd 1 1 3/31/174/5/17 7:533:59 AMPM TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 Recognition, Successorship and Mergers . 1 Section 2 Definitions . 4 Section 3 General . 10 Section 4 Compensation . 28 Section 5 Expenses, Transportation and Lodging . 36 Section 6 Minimum Pay and Credit, Hours of Service, and Contractual Legalities . 42 Section 7 Scheduling . 56 Section 8 Reserve Scheduling Procedures . 88 Section 9 Special Qualification Flight Attendants . 107 Section 10 AMC Operation . .116 Section 11 Training & General Meetings . 120 Section 12 Vacations . 125 Section 13 Sick Leave . 136 Section 14 Seniority . 143 Section 15 Leaves of Absence . 146 Section 16 Job Share and Partnership Flying Programs . 158 Section 17 Filling of Vacancies . 164 Section 18 Reduction in Personnel . .171 Section 19 Safety, Health and Security . .176 Section 20 Medical Examinations . 180 Section 21 Alcohol and Drug Testing . 183 Section 22 Personnel Files . 190 Section 23 Investigations & Grievances . 193 Section 24 System Board of Adjustment . 206 Section 25 Uniforms . 211 Section 26 Moving Expenses . 215 Section 27 Missing, Interned, Hostage or Prisoner of War . 217 Section 28 Commuter Program . 219 Section 29 Benefits . 223 Section 30 Union Activities . 265 Section 31 Union Security and Check-Off . 273 Section 32 Duration . 278 i LETTERS OF AGREEMENT LOA 1 20 Year Passes . 280 LOA 2 767 Crew Rest . 283 LOA 3 787 – 777 Aircraft Exchange . 285 LOA 4 AFA PAC Letter . 287 LOA 5 AFA Staff Travel . -

Volume I Restoration of Historic Streetcar Service

VOLUME I ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT RESTORATION OF HISTORIC STREETCAR SERVICE IN DOWNTOWN LOS ANGELES J U LY 2 0 1 8 City of Los Angeles Department of Public Works, Bureau of Engineering Table of Contents Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................. ES-1 ES.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... ES-1 ES.2 Purpose and Need ............................................................................................................................................... ES-1 ES.3 Background ............................................................................................................................................................ ES-2 ES.4 7th Street Alignment Alternative ................................................................................................................... ES-3 ES.5 Safety ........................................................................................................................................................................ ES-7 ES.6 Construction .......................................................................................................................................................... ES-7 ES.7 Operations and Ridership ............................................................................................................................... -

Télécharger La Synthèse De L'enquête Nationale Sur L'autopartage 2019

Enquête nationale sur l’autopartage - Edition 2019 Actualisation et étude de l’impact des services d’autopartage sur l’équipement des ménages et sur les kilomètres parcourus en voiture UNE ÉTUDE RÉALISÉE PAR 6T-BUREAU DE RECHERCHE SUR UN COFINANCEMENT 6T ET ADEME Contexte Enjeux Publiées en 2012 et 2016, les deux premières Tout comme en 2012 et 2016, l’édition 2019 porte éditions de l’Enquête Nationale sur l’Autopartage1 principalement sur l’autopartage en boucle. Elle vise constituaient les premières études d’envergure sur deux objectifs : les usagers, usages et impacts de l’autopartage en France. mettre à jour les résultats de la précédente édition : les usagers, usages et impacts de l’autopartage ont- Menées auprès d’au moins 2 000 usagers abonnés ils évolué entre 2016 et 2019 ? d’une vingtaine de services d’autopartage différents, ces enquêtes ont mis en évidence l’effet « déclencheur affiner la compréhension des usagers, usages et de multimodalité » de l’autopartage en boucle : impacts de l’autopartage : notamment, qui sont les l’autopartage permet aux habitants des villes de usagers de l’autopartage ? Une fois abonnés à s’affranchir de la voiture individuelle, de découvrir l’autopartage, leurs pratiques de déplacements et de s’approprier d’autres modes de déplacement. évoluent-elles de la même manière ? Quels sont les usages et les impacts de l’autopartage entre Trois ans après la dernière enquête, l’autopartage particuliers et de l’autopartage en contexte joue-t-il encore le même rôle dans la mobilité professionnel ? urbaine ? Ses usagers sont-ils restés les mêmes ? Ses usages, ses impacts ont-ils évolué ? Le rapport d’étude complet est disponible sur notre blog : Lien Autopartage B2C en boucle : (fr Autopartage B2C en trace Autopartage entre l’objet principal de l’étude directe particuliers ou P2P Le véhicule est rendu dans la Avec stations : le véhicule peut Réalisée entre particuliers station de départ. -

Monday Through Friday Mt

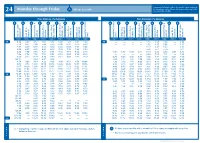

New printed schedules will not be issued if trips are adjusted Monday through Friday All trips accessible by five minutes or less. Please visit www.go-metro.com for the go smart... go METRO 24 most up-to-date schedule. 24 Mt. Lookout–Uptown–Anderson Riding Metro From Anderson / To Downtown From Downtown / To Anderson . 1 No food, beverages or smoking on Metro. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 2. Offer front seats to older adults and people with disabilities. METRO* PLUS 3. All Metro buses are 100% accessible for people 38X with disabilities. 46 UNIVERSITY OF 4. Use headphones with all audio equipment 51 CINCINNATI GOODMAN DANA MEDICAL CENTER HIGHLAND including cell phones. Anderson Center Station P&R Salem Rd. & Beacon St. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Liberty St. & Sycamore St. Square Government Area B Square Government Area B Liberty St. & Sycamore St. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly Salem Rd. & Beacon St. Anderson Center Station P&R 11 ZONE 2 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 2 43 5. Fold strollers and carts. BURNET MT. LOOKOUT AM AM 38X 4:38 4:49 4:57 5:05 5:11 5:20 5:29 5:35 5:40 — — — — 4:10 4:15 4:23 — 4:35 OBSERVATORY READING O’BRYONVILLE LINWOOD 6. -

Evolution of E-Mobility in Carsharing Business Models

Evolution of E-Mobility in Carsharing Business Models Susan A. Shaheen1 and Nelson D. Chan2 Transportation Sustainability Research Center, University of California, Berkeley, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Carsharing continues to grow worldwide as a powerful strategy to provide an alternative to solo driving. The viability of electric vehicles, or EVs, has been examined in various carsharing business models. Moreover, new technologies have given rise to electromobility, or e-mobility, systems. This paper discusses the evolution of e-mobility in carsharing business models and the challenges and opportunities that EVs present to carsharing operators around the world. Operators are now anticipating increased EV proliferation into vehicle fleets over the next 5- 10 years as technology, infrastructure, and public policy shift toward support of e- mobility systems. Thus, research is still needed to quantify impacts of EVs in changing travel behavior toward more sustainable transport. 1 Introduction Carsharing enables a group of members to share a vehicle fleet that is maintained, managed, and insured by a third-party organization. Primarily used for short-term trips, carsharing can provide affordable, self-service vehicle access 24-h per day for those who do not have a car, want to reduce the number of vehicles in their household, or do not use their vehicle during the day for long periods of time. Rates include fuel, insurance, and maintenance. Ideally, carsharing works best in a neighborhood, business, or campus setting where users could walk, bike, share rides, or take public transit to access the shared-use vehicles. Carsharing has evolved through several phases since the first carsharing system began in Europe in 1948. -

Sharing and Tourism: the Rise of New Markets in Transport

SHARING AND TOURISM: THE RISE OF NEW MARKEts IN TRANSPORT Documents de travail GREDEG GREDEG Working Papers Series Christian Longhi Marcello M. Mariani Sylvie Rochhia GREDEG WP No. 2016-01 http://www.gredeg.cnrs.fr/working-papers.html Les opinions exprimées dans la série des Documents de travail GREDEG sont celles des auteurs et ne reflèlent pas nécessairement celles de l’institution. Les documents n’ont pas été soumis à un rapport formel et sont donc inclus dans cette série pour obtenir des commentaires et encourager la discussion. Les droits sur les documents appartiennent aux auteurs. The views expressed in the GREDEG Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the institution. The Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Sharing and Tourism: The Rise of New Markets in Transport Christian Longhi1, Marcello M. Mariani2 and Sylvie Rochhia1 1University Nice Sophia Antipolis, GREDEG, CNRS, 250 rue A. Einstein, 06560 Valbonne France [email protected], [email protected] 2University of Bologna, Via Capo di Lucca, 34 – 40126, Bologna, Italy [email protected] GREDEG Working Paper No. 2016-01 Abstract. This paper analyses the implications of sharing on tourists and tourism focusing on the transportation sector. The shifts from ownership to access, from products to services have induced dramatic changes triggered by the emergence of innovative marketplaces. The services offered by Knowledge Innovative Service Suppliers, start-ups at the origin of innovative marketplaces run through platforms allow the tourists to find solutions to run themselves their activities, bypassing the traditional tourism industry. -

Balancing Passenger Preferences and Operational Efficiency in Network

Risk Averseness Regarding Short Connections in Airline Itinerary Choice AV020 Annual Meeting 2006 Submission Date: 01 April 2006, Word Count: 6902 By: Georg Theis Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Room 35-217 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Tel.: (617) 253-3507 Fax: (270) 968-5529 Email: [email protected] Thomas Adler Resource Systems Group 55 Railroad Row White River Junction, VT 05001 Tel.: (802) 295-4999 Fax: (802) 295-1006 Email: [email protected] John-Paul Clarke School of Aerospace Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0150 Tel: (404) 385-7206 Fax: (404) 894-2760 Email: [email protected] Moshe Ben-Akiva Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Room 1-181 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Tel.: (617) 253-5324 Fax: (617) 253-0082 Email: [email protected] Theis et al. 2 ABSTRACT Network airlines traditionally attempt to minimize passenger connecting times at hub airports based on the assumption that passengers prefer minimum scheduled elapsed times for their trips. Minimizing connecting times, however, creates peaks in hub airports’ schedules. These peaks are extremely cost intensive in terms of additional personnel, resources, runway capacity and schedule recovery. Consequently, passenger connecting times should only be minimized if the anticipated revenue gain of minimizing passenger connecting times is larger than the increase in operating cost, i.e. if this policy increases overall operating profit. This research analyzes to what extent a change in elapsed time impacts passenger itinerary choice and thus an airline’s market share. We extend an existing airline itinerary choice survey to test the assumption that passenger demand is affected by the length of connecting times. -

A Collaborative Design Process to Support Sustainable

SCENARIODEVELOPMENTINPRODUCTSERVICESYSTEMS: ACOLLABORATIVEDESIGNPROCESSTOSUPPORT SUSTAINABLECONSUMPTION CatharinaB.Nawangpalupi Athesissubmittedforthedegreeof DoctorofPhilosophy FACULTYOFTHEBUILTENVIRONMENT THEUNIVERSITYOFNEWSOUTHWALES COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). I have either used no substantial portions of copyright material in my thesis or I have obtained permission to use copyright material; where permission has not been granted I have applied/will apply for a partial restriction of the digital copy of my thesis or dissertation.' Signed Date 2 August 2010 AUTHENTICITY STATEMENT ‘I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. No emendation of content has occurred and if there are any minor variations in formatting, they are the result of the conversion to digital format.’ Signed Date 2 August 2010 i ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. -

Benchmarking of Existing Business / Operating Models & Best Practices

SHared automation Operating models for Worldwide adoption SHOW Grant Agreement Number: 875530 D2.1.: Benchmarking of existing business / operating models & best practices This report is part of a project that has received funding by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement number 875530 Legal Disclaimer The information in this document is provided “as is”, and no guarantee or warranty is given that the information is fit for any particular purpose. The above-referenced consortium members shall have no liability to third parties for damages of any kind including without limitation direct, special, indirect, or consequential damages that may result from the use of these materials subject to any liability which is mandatory due to applicable law. © 2020 by SHOW Consortium. This report is subject to a disclaimer and copyright. This report has been carried out under a contract awarded by the European Commission, contract number: 875530. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the SHOW project. D2.1: Benchmarking of existing business / operating models & best practices 2 Executive Summary D2.1 provides the state-of-the-art for business and operating roles in the field of mobility services (MaaS, LaaS and DRT containing the mobility services canvas as description of the selected representative mobility services, the business and operating models describing relevant business factors and operation environment, the user and role analysis representing the involved user and roles for the mobility services (providing, operating and using the service) as well as identifying the success and failure models of the analysed mobility services and finally a KPI-Analysis (business- driven) to give a structured economical evaluation as base for the benchmarking. -

Matching the Speed of Technology with the Speed of Local Government: Developing Codes and Policies Related to the Possible Impacts of New Mobility on Cities

Final Report 1216 June 2020 Photo by Cait McCusker Matching the Speed of Technology with the Speed of Local Government: Developing Codes and Policies Related to the Possible Impacts of New Mobility on Cities Marc Schlossberg, Ph.D. Heather Brinton NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNITIES nitc-utc.net MATCHING THE SPEED OF TECHNOLOGY WITH THE SPEED OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT Developing Codes and Policies Related to the Possible Impacts of New Mobility on Cities Final Report NITC-RR-1216 by Marc Schlossberg, Professor Department of Planning, Public Policy and Management University of Oregon Heather Brinton, Director Environment and Natural Resources Law Center University of Oregon for National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) P.O. Box 751 Portland, OR 97207 June 2020 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. NITC-RR-1216 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date June 2020 Matching the Speed of Technology with the Speed of Local Government: Developing Codes and Policies Related to the Possible Impacts of New Mobility on Cities 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Marc Schlossberg Report No. Heather Brinton 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) University of Oregon 1209 University of Oregon 11. Contract or Grant No. Eugene, OR 97403 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) P.O. Box 751 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Portland, Oregon 97207 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract Advances in transportation technology such as the advent of scooter and bikeshare systems (micromobility), ridehailing, and autonomous vehicles (AV’s) are beginning to have profound effects not only on how we live, move, and spend our time in cities, but also on urban form and development itself. -

The Future of Car Ownership August 2017 About the NRMA

Future mobility series The future of car ownership August 2017 About the NRMA Better road and transport infrastructure has been a core focus of the NRMA since 1920 when our founders lobbied for improvements to the condition of Parramatta Road in Sydney. Independent advocacy was our foundation activity, and it remains critical to who we are as we approach our first centenary. We’ve grown to represent over 2.4 million Australians, principally from New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. We provide motoring, mobility and tourism services to our Members and the community. Today, we work with policy makers and industry leaders, advocating for increased investment in road infrastructure and transport solutions to make mobility safer, provide access for all, and deliver sustainable communities. By working together with all levels of government to deliver integrated transport options, we give motorists real choice about how they get around. We firmly believe that integrated transport networks, including efficient roads, high-quality public transport and improved facilities for cyclists and pedestrians, are essential in addressing the challenge of growing congestion and providing for the future growth of our communities. The NRMA acknowledges the work of Sam Rutherford on this report. Comments and queries Ms Carlita Warren Senior Manager – Public Policy and Research NRMA PO Box 1026, Strathfield NSW 2135 Email: [email protected] Web: mynrma.com.au Cover Image: nadla – Getty Images Contents Executive summary 2 Challenges -

Memo Relevant to Item

Item 9.2 At Council 21 November 2016 RELEVANT INFORMATION FOR COUNCIL FILE: S116884.008 DATE: 21 November 2016 TO: Lord Mayor and Councillors FROM: Graham Jahn, Director City Planning, Development and Transport SUBJECT: Information Relevant To Item 9.2 – Post Exhibition - Draft Car Sharing Policy 2016 - At Council - 21 November 2016 Alternative Recommendation It is resolved that: (A) the draft Car Sharing Policy 2016, as shown at Attachment A to the subject report, be adopted, subject to the amendment of clause 5.2 such that it read as follows (with additions shown in bold italics and deletions shown in strikethrough): 5.2 Preferential Allocation In precincts where more than 75% of potential on-street spaces in a precinct are held by a single operator, the City may choose to will issue remaining spaces preferentially to another eligible operator in order to facilitate competition and user choice. (B) a revised car sharing permit fee be publicly advertised in accordance with the requirements of the Local Government Act 1993. Background At the meeting of the Planning and Development Committee (Transport, Heritage and Planning Sub-Committee) on 14 November 2016, further information was sought. 1. Preferential allocation of on-street spaces The draft Policy 2016 proposes that, in precincts where more than 75% of the total potential on-street car share spaces are held by a single operator, the City may choose to issue remaining spaces preferentially to another eligible operator in order to facilitate competition and user choice within precincts. After discussion in Committee, further examination of potential mechanisms to operationalise this has identified some potential implementation and probity issues.