Historical Evolution of the Bow: Longbow Vs. Crossbow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARROWS SUPREME, by American

CROSSBOWS FOR VIETNAM! VOLCANOLAND HUNTING PROFESSIONAL PERFORMANCE GUARANTEED OR YOUR MONEY BACK! the atomic bow The bold techniques of nuclear impregnated with a plastic mon chemistry have created the first omer and then atomically hard major chang,e in bowmaking ma ened. Wing's PRESENTATION II terials since the introduction of is a good example of the startling fiberglas. For years, archery results! The Lockwood riser in people have been looking for this bow is five times stronger improved woods. We've wanted than ordinary wood. It has 60% more beautiful types. Stronger more mass weight to keep you 1 woods. Woods with more mass on target. It has greater resist weight. We've searched for ways ance to abrasion and moisture. to protect wood against mois~ And the natural grain beauty of ture. What we were really after the wood is brought out to the turned out to be something bet fullest extent by the Lockwood COMING APRIL 1 &2 ter than the real thing. Wing found process. The PRESENTATION II 9th Annual International it in new Lockwood. An out PRESENTATION II. .. ......... •• $150.00 is one of several atomic bows Fair enough! I'm Interested In PROFESSIONAL PERFORMANCE growth of studies conducted by PRESENTATION I . ••• . •.• . •• •• $115.00 Indoor Archery Tournament waiting for you at your Wing the Atomic Energy Commission, WHITE WING • . • • • • • • . • . • • . • • $89.95 dealer. Ask him to show you our World's Largest SWIFT WING ..• ••••. ••••• •• $59.95 Lockwood is ordinary fine wood FALCON ••.••• •••• • . ••••. •• $29.95 new designs for 1967. Participating Sports Event Cobo Hall, Detroit Sponsored by Ben Pearson, Inc. -

Arrow Company Profile

Fact Sheet Executive Officers Arrow Company Michael J. Long Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer Profile Paul J. Reilly Arrow is a global provider of products, services, and solutions to industrial Executive Vice President, Finance and Operations, and Chief Financial Officer and commercial users of electronic components and enterprise computing solutions, with 2012 sales of $20.4 billion. Arrow serves as a supply channel Peter S. Brown partner for over 100,000 original equipment manufacturers, contract Senior Vice President, General Counsel manufacturers, and commercial customers through a global network of more and Secretary than 470 locations in 55 countries. A Fortune 150 company with 16,500 Andrew S. Bryant employees worldwide, Arrow brings the technology solutions of its suppliers President, Global Enterprise to a breadth of markets, including industrial equipment, information systems, Computing Solutions automotive and transportation, aerospace and defense, medical and life Vincent P. Melvin sciences, telecommunications and consumer electronics, and helps customers Vice President and Chief Information Officer introduce innovative products, reduce their time to market, and enhance their M. Catherine Morris overall competiveness. Senior Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer FAST FACTS Eric J. Schuck President, Global Components > Ticker Symbol: ARW (NYSE) > Fortune 500 Ranking1: 141 Gretchen K. Zech > 2012 Sales: $20.4 billion > Employees Worldwide: 16,500 Senior Vice President, Global Human - Global Components: $13.4 > Customers Worldwide: 100,000 Resources billion - Global Enterprise Computing > Industry: Electronic Solutions: $7 billion Components and Computer Products Distribution 20122012 Sales Sales by Geographic by Geographic Region Region > 2012 Net Income: $506.3 million > Founded: 1935 19% ASIA/PACIFIC > 2012 Operating Income: > Incorporated: 1946 52% AMERICAS $804.1 million > Public: 1961 > 2012 EPS: $4.56 > Website: www.arrow.com > Locations: more than 470 worldwide 29% 1 Ranking of the largest U.S. -

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1 B.W. Kooi Groningen, The Netherlands 1983 1B.W. Kooi, On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow PhD-thesis, Mathematisch Instituut, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, The Netherlands (1983), Supported by ”Netherlands organization for the advancement of pure research” (Z.W.O.), project (63-57) 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Prefaceandsummary.............................. 5 1.2 Definitionsandclassifications . .. 7 1.3 Constructionofbowsandarrows . .. 11 1.4 Mathematicalmodelling . 14 1.5 Formermathematicalmodels . 17 1.6 Ourmathematicalmodel. 20 1.7 Unitsofmeasurement.............................. 22 1.8 Varietyinarchery................................ 23 1.9 Qualitycoefficients ............................... 25 1.10 Comparison of different mathematical models . ...... 26 1.11 Comparison of the mechanical performance . ....... 28 2 Static deformation of the bow 33 2.1 Summary .................................... 33 2.2 Introduction................................... 33 2.3 Formulationoftheproblem . 34 2.4 Numerical solution of the equation of equilibrium . ......... 37 2.5 Somenumericalresults . 40 2.6 A model of a bow with 100% shooting efficiency . .. 50 2.7 Acknowledgement................................ 52 3 Mechanics of the bow and arrow 55 3.1 Summary .................................... 55 3.2 Introduction................................... 55 3.3 Equationsofmotion .............................. 57 3.4 Finitedifferenceequations . .. 62 3.5 Somenumericalresults . 68 3.6 On the behaviour of the normal force -

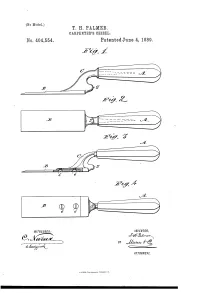

T. H. Palmer. Oarpentbb’S Chisel

(No Model.) T. H. PALMER. OARPENTBB’S CHISEL. _ No. 404,554. I PatentedJune 4, 1889. J , J WITNESSES : 4 ' l/VIg/VTOR ATTOHIVEYJ, UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. THE'RON H. PALMER, OF SAN BERNARDINO, CALIFORNIA. CARPENTER’S CHISEL._ SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 404,554, dated June 4, 1889. I Application ?led May 22, 1888.‘ Serial No. 274,724. (No model.) To all whom it may concern; 2, or it may be of a separate piece of mallea Be it known that I, THERON H. PALMER, of ble cast~ir0n or other suitable material and 40 the city and county of San Bernardino, and be joined to the blade B by screws 1) b or oth State of California, have invented a new and erwise. The shank may be secured in the. useful Improvement in Carpenters’ Chisels, handle by a simple tang or in any other de of which the following is a full, clear, and ex sired manner. The trowel-like shape of the act description. ~ > tool provides for cutting gains across a wide 45 This invention consists in a chisel or gouge surface without risk of obstruction by the ' _ for carpenters’ use which has its shank and handle, or the tool may be used as a paring handle portion bent out of line with its blade chisel or for cutting and ?tting in butts or or cutting portion and which is provided with hinges. The crooked shank O is provided at an anvil or hammer-block in rear of the blade its back, as nearly in the same plane as the to form a striking-surface when usingahani cu ttin g-blade as practicable, with aknob-like mer or mallet to force the cutting-tool up to projection S, forming a special anvil or ham its work, instead of striking on the end of mer-block to receive the blows of a hammer the handle direct, which is liable to split or bruise the handle. -

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon William J. Hamblin The distinctive characteristic of missile weapons used in combat is that a warrior throws or propels them to injure enemies at a distance.1 The great variety of missiles invented during the thousands of years of recorded warfare can be divided into four major technological categories, according to the means of propulsion. The simplest, including javelins and stones, is propelled by unaided human muscles. The second technological category — which uses mechanical devices to multiply, store, and transfer limited human energy, giving missiles greater range and power — includes bows and slings. Beginning in China in the late twelfth century and reaching Western Europe by the fourteenth century, the development of gunpowder as a missile propellant created the third category. In the twentieth century, liquid fuels and engines have led to the development of aircraft and modern ballistic missiles, the fourth category. Before gunpowder weapons, all missiles had fundamental limitations on range and effectiveness due to the lack of energy sources other than human muscles and simple mechanical power. The Book of Mormon mentions only early forms of pregunpowder missile weapons. The major military advantage of missile weapons is that they allow a soldier to injure his enemy from a distance, thereby leaving the soldier relatively safe from counterattacks with melee weapons. But missile weapons also have some signicant disadvantages. First, a missile weapon can be used only once: when a javelin or arrow has been cast, it generally cannot be used again. (Of course, a soldier may carry more than one javelin or arrow.) Second, control over a missile weapon tends to be limited; once a soldier casts a missile, he has no further control over the direction it will take. -

Shooting the Longbow

Shooting the Longbow Some coaching tips Steve Purkiss (Fox Archers) Equipment Bows Longbows, being made from wood, need to be protected from the elements. Even a “varnished” bow can let in moisture due to marks and scratches from regular use. Polish the bows with a wax polish, Danish Oil or even a smear of vaseline to help keep out the wet which can ruin your bow. Pay special attention to the area where the arrow “passes” the bow as obvious wear will take it down to exposed wood. Also keep the string waxed, most modern strings are fairly waterproof but as the string is twisted and the strands rub against each other under tension waxing helps cut down wear. Apply wax to the string and then rub with a small piece of leather this warms the wax and string and helps the wax to move between the strands. If you are used to shooting a recurve bow then you will find that the draw weight of a longbow feels different to a recurve simply due to the nature of the beast and therefore if you are used to a 30lb recurve you might find a 35lb longbow comfortable. The bracing height of the bow is the distance from the string to the belly of the bow (the part of the bow facing you when you hold it to shoot). This is often written on the bow (normally 5.5” to 6.5”) set your bow up to this height for optimum performance. Always “warm up” your bow before you shoot, this is done by rubbing the bow with a cloth and then repeatedly drawing the bow to half draw and gradually increasing to full draw either in the normal manner of by putting your foot against the grip and holding the string then you can use you foot and hand to extend the bow. -

Making Arrows Ronald A

Fact Sheet 6 Making Arrows Ronald A. Howard Jr.* Many archers enjoy making increase arrow mass. Wooden been exposed to the graphite their own arrows because it shafts must be lacquered or fibers. Those fibers are hard, allows them to exercise painted full length to protect stiff and fine. They survive personal quality control, add them from moisture. cooking well and can cause injury if swallowed. Many special features, personalize the Fiberglass shafts are lighter than target archers, particularly arrows in other ways or add to wooden shafts of the same spine those shooting bows equipped their shooting enjoyment. weight. They remain relatively with overdraws, prefer graphite Making arrows involves straight, and they can be matched shafts. several steps, but it is not in spine and arrow mass much difficult. High quality arrows better than wooden shafts. Aluminum shafts have been the can be made with care and Although fiberglass is a tough standard of both target archers attention to detail. material, these shafts are subject and bowhunters for many Shaft Selection to splitting on impact. They also years. The shafts can be made tend to shatter or splinter if to very close tolerances in a The first step is selecting the variety of alloys, offering easy shaft type and size desired. struck along their length. Shafts with internal damage may even matching in spine and weight. Arrow shafts are available in Aluminum shaft materials may wood, fiberglass, graphite, shatter during a release. Fiberglass has been an excellent be obtained in inexpensive soft aluminum and graphite- alloys that are easily bent or aluminum combinations. -

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Klopsteg, Turkish Archery & the Composite

FfootJiptecc: Sketch of a Turkish archcr at full draw, ready to loose a flight arrow. [Based on a photoK'aph by Dr. Stocklcin published in llalıl I.them “U Palai* Dc Topkapou (Vicux Scrail)”. Mitnm. <k U Ltbratic Kanaat 1931 page 17. Information supplied by Society of Archcr-Antiquaries member Jamcr. H. Wiggins. | TURKISH ARCHERY AND THE COMPOSITE BOW by Paul E. Klopsteg F ormer D irector of R esearch N orthwestern T echnological I nstitute A Review of an old Chapter in the Chronicles of Archery and a Modern Interpretation Enlarged Third Edition Simon Archery Foundation The Manchester Museum, The University Manchester M139PL, Kngland Also published by the Simon Archcry Foundation: A Bibliography of Arthtry by Fred Lake and HaJ W right 1974 ISBN 0 9503199 0 2 Brazilian India» Arcbeiy bv E. G. Heath and Vilma Chiara 1977 ISBN 0 9503199 1 0 Toxopbilns by Roger Ascham 1985 ISBN 0 9503199 0 9 @ Paul E. Klopsteg, 1934, 1947 and 1987 First published by rhe author in the U.S.A. in 1934 Second edition, Revised published by the author in the U.S.A. in 1947 This enlarged edition published in 1987 JSBN 0 9503199 3 7 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London c^ pur TABLE 0F CONTENTS Pa& In troduction ....................... ............................... ................................. Y|J Dr. Paul E. Klopsteg. Excerpts about him from articles written by him ...................................... ; .............................................................. IX Preface to the Second E d itio a ............................................................... xiii Preface to the First E dition........................................................ I The Background of Turkish Archery..................................... 1 II The Distance Records of the Turkish Bow......................... -

Ohio Archaeologist Volume 43 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 43 NO. 2 SPRING 1993 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first TERM of January as follows: Regular membership $17.50; husband and wife EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS (one copy of publication) $18.50; Life membership $300.00. Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included in the member 1994 President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East ship dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an incorporated non Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 profit organization. 1994 Vice President Stephen J. Parker, 1859 Frank Drive, Lancaster, OH 43130, (614)653-6642 BACK ISSUES 1994 Exec. Sect. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43130,(614)653-9477 Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 add $1.50 P-H SE. East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse .$20.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, 1980's & 1990's $ 6.00 add $1.50 P-H OH 43068, (614)861-0673 1970's $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH 1960's $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are gener ally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

World Crossbow Shooting Association - TARGET, STANDARD, FREESTYLE & MEDIEVAL CROSSBOW RULES

World Crossbow Shooting Association - TARGET, STANDARD, FREESTYLE & MEDIEVAL CROSSBOW RULES WORLD CROSSBOW SHOOTING ASSOCIATION SHOOTING RULES FOR TARGET, MEDIEVAL, STANDARD, FREESTYLE CROSSBOWS AND GENERAL SHOOTING RULES. EFFECTIVE 1st January 2019 Effective, 1st January 2019 Page: 1 World Crossbow Shooting Association - TARGET, STANDARD, FREESTYLE & MEDIEVAL CROSSBOW RULES INDEX Clause Item Page No INDEX ................................................................................................................................................................................. .................. 2 DEFINITIONS ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 SECTION 1. WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS, REGINAL CHAMPIONSHIP, JUDGING, RECORDS, ASSISTED SHOOTERS 1 PRECEDENCE, INTERPRETATION AND AMENDMENTS ..................................................................................................... 9 2 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Outdoor Target ................................................................................................................................................................ 2.2 3D ................................................................................................................................................................................... -

BRITISH Mingclbut and BRITISH Crvil POLICIES CTNDER the EARLY STUARTS

THE SOVEREIGN OF ALL THESE ISLES: BRITISH MINGClbUT AND BRITISH CrVIL POLICIES CTNDER THE EARLY STUARTS A Thesis Presented to The Factg of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by ANDREW D. NICHOLLS In partial falfilment of reqoirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Jnne, 1997 O Andrew D. Nicholls, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Lhrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distnibute or sell reproduire, prêter, &strri.uer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownefship of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT THE SOVEREIGN OF ALL THESE ISLES: BRITISH KINGCRAFT AND BRITISH CML POLICIES UNDER THE EARLY STUARTS Andrew D. Nichoiis Advisors: University of Guelph, 1997 Dr. J.D. Alsop Dr. Donna Andrew This thesis is concemed with the challenge of multiple rule in the British Isles and extent to which the early Stuart monarchs, James VI and 1, and Charles 1, identified issues which were common to England, Scotland, and Lreland.