My First Innings at Patna : Part-I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

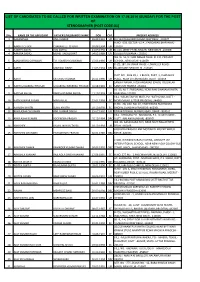

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

JMSCR Vol||07||Issue||08||Page 09-13||August 2019

JMSCR Vol||07||Issue||08||Page 09-13||August 2019 http://jmscr.igmpublication.org/home/ ISSN (e)-2347-176x ISSN (p) 2455-0450 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.18535/jmscr/v7i8.02 Skeletal Metastasis in Carcinoma Gallbladder Authors Dr Satyendra Narayan Sinha1*, Dr Madhulika2, Dr Manisha Singh3 1Radiation Oncology Department, Paras HMRI Hospital, Patna (India) 2Medical Oncology Department, Mahavir Cancer Sansthan, Phulwarisharif, Patna (India) 3Head, Medical Oncology Department, Mahavir Cancer Sansthan, Phulwarisharif, Patna (India) *Corresponding Author Dr Satyendra Narayan Sinha Radiation Oncology Department, Paras HMRI Hospital, Patna (India) Abstract Gallbladder carcinoma is the 5th most common gastrointestinal tract cancers and is an aggressive malignancy with varied presentation. The predominant sites of mestatasis being liver and regional lymph nodes. Skeletal metastasis in gallbladder carcinoma is very rare and only 15 cases have been reported in English literature so far. In this manuscript, we describe our experience of two cases of skeletal metastasis in carcinoma gallbladder. Keywords: Gallbladder Cancer, Skeletal Metastasis in Gallbladder Cancer, Bony Metastasis. Introduction Case Report – 1 Gallbladder cancer is the most common of all the A normotensive and nondiabetic male patient of biliary tract cancers and is fifth most common of age 30 year from Patna (India) presented to the gastrointestinal tract. Gallbladder cancer Mahavir Cancer Sansthan on 8th January 2018 preferentially metastasizes to regional lymph with complain of right hypochondrial pain and nodes and liver parenchyma. Bone metastasis severe back pain for last 3 months. There is past from gallbladder carcinoma are rare presentation. history of lap cholecystectomy and In a study by Sameer G et al.[1] 2.5% patients have appendicectomy on 26th September 2017 outside cytologically proven skeletal metastasis. -

District Health Plan 2010-2011

District Health Plan 2010-2011 District Health Society, Gaya 1 Foreword NRHM was launched in April 2005. The State Health Society (Bihar) and the District Health Societies (Gaya) were formed by end of 2005. The recruitment of Block level managers and other staff were completed by May 2007. The data centre was established by 2006, which worked on outsourced mode. However, a new system replaced the out sourced mode and the data centres were put in place by 2008. Public health system has witnessed an increased utilization of services in 2009 reflected by an increased number of persons being provided every type of service that is available- be it outpatient care, inpatient care, institutional delivery services or emergency services, or surgical services, or laboratory services. The strategy of revitalizing the BPHC and District hospital has shown results. Human resources and Quality of services remains an issue that needs to be addressed. The District Health Planning in Gaya used a situational analysis form focusing on areas in health covered by NRHM viz; RCH, NRHM Additionalities, Immunization, Disease control, and Convergence. This DHAP has been evolved through a participatory and consultative process, wherein community, NGO and other stakeholders have participated and deliberated on the specific health needs. I need to congratulate the SHS Bihar for its dynamic leadership and enthusiasm provided to district level so that the plan is made. We also acknowledge PHRN (NGO partner) for organizing the capacity building programme for the preparation of District Health Action Plan. This District Health Action Plan (DHAP) is one of the key instruments to achieve NRHM goals. -

BIHAR and ORISS ~. Iii

I ll III BIHAR AND ORISS ~. iii IN UY C. R. B. MlTRRAY, Indian Puiice. SliPF.RI. 'ITI\OE'IT. C(J\ ER \ ,'1 F.:\T I 'I·T, I I 'IG, Ulll \R A'ID ORIS-; ..\ . P \T\' \ I!. 1930. I' , I hIt t' - f: I . 1 ] BIHAR AND ORISSA IN 1928-29 BY C. R. B. MURRAY. Indian Police. SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BIHAR AND ORISSA, PATNA 1930, Priced Publications of the Government of Bihar and Orissa can be had from- IN INDIA The Superintendent, Government Printing, Bihar and Orissa, Gulzarbagh P. 0. (1) Mlssu. TRAcJWI. SPOOl: & Co., Calcutta. (2) Ml:sSB.s, W. N&WM.AN & Co., Calcutta. (3) Missu. S. K. L.uo:m & Co., College Street, Calcutta. (4) Missll.s. R. CAlllli.B.AY & Co.,. 6 and 8-2, Hastings Street, Calcutta. (5) MzsSB.s. Tno.I4PsoN & Co., Madraa. (6) MisSB.s. D. B. TAJW>O:UVALA SoNs & Co., 103, Meadow Street, Fort, Poat Box No. 18, B,ombay. (7) MissBs. M. C. Slll.IUll. & SoNs, 75, Harrison Road, Calcutta, (8) P:a.oPlUITO:B. or ru:& NxwAL KlsnoBB Puss, Luclmow. (9) Missu. M. N. BU1WAN & Co., Bankipore. (10) Buu R.ul DAYAL AaAB.WALA, 184, Katra Road, Allo.habad. (U) To Sr.uro.um L.rmurmlll Co., Lrn., 13-1, Old Court House Street, Calcutta. (12) M.uuau OJ' TH.I INDIAN Scnoot. SUPPLY Dll'Or, 309, Bow Bazar Streei, Calcutta. (13) MESS.Il.'l. BtJ'.I'Tili.WOBm & Co., Lrn., 6, Hastings Street, Calcutta. (14) Mxssns. RAll KmsHNA & SoNs, Anarkali Street, Lahore. (15) TH.I Ouoli.D BooK Al!D S:urroNERY CoMPANY, Delhi, (16) MESSRS. -

Spotlaw 2014

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Krishna Ballabh Sahay Vs. Commission of Inquiry C.A.No.150 of 1968 (M. Hidayatullah, C.J.I., J. C. Shah, V. Ramaswami, V. Bhargava and C. A. Vaidialingam, JJ.) 18.07.1968 ORDER:- 1. The Appeal shall stand dismissed, but there shall be no order as to costs. Reasons for our judgment will follow. Stay order is vacated. 2. The following Judgment of the Court was delivered by HIDAYATULLAH, C.J.: This appeal is brought against an order of the High Court at Patna, November 4, 1967, dismissing a petition under Arts. 226 and 227 of the Constitution. By that petition the appellants sought a declaration that a notification of the Governor of Bihar appointing a Commission of Inquiry under the Commissions of Inquiry Act, 1952, was 'ultra vires' illegal and inoperative' and for restraining the Commission from proceeding with the Inquiry. The High Court dismissed the petition without issuing a rule but gave detailed reasons in its orders. The appellants now appeal by special leave granted by this Court. After the hearing of the appeal concluded we ordered the dismissal of the appeal but reserved the reasons which we now proceed to give. 3. As is common knowledge there was for a time no stable Government in Bihar. The Congress Ministry continued in office for some time under Mr. Binodanand Jha and then under the first appellant, Mr. K. B. Sahay. When the Congress Ministry was voted out of office, a Ministry was formed by the United Front Party headed by Mr. Mahamaya Prasad Sinha. -

The Banaras Hindu University (Amendment) Bill, 195 8

C.B. (II) No. -p. LOK SABHA THE BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY (AMENDMENT) BILL, 195 8 (Report of the SeleCt Committee) PREsENTED ON lliB" 27TH AUGUST, 1958 T4.2,dN15:(Z).N58t JB 060192 .. LOlt SABRA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Aagast, 19S8 CONTE NTis PAGES 1, Composition of the Select Committee i-ii 2. Report of the Select Commi~tee .. iili-v 3· Minutes of Dissent Vi-xvili 4· Bill as amended by the Select Committee APPENDIX I Motion in Lok Sabha for reference of the Bill to Select Committee 9-10 APPENDIX II Minutes of the sittings of the Select Committee • • APPENDIX III Documents circulated to the Select Committee and approved b y them for presentation to Lok Sabha 26-58 838 LS-1. THE BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY (AMENDMENT) BILL, 1958. Composition of the Select Committee 1. Sardar Hukam Singh-Chairman. 2. Shri Banarasi Prasad Jhunjhunwala 3. Shri Satyendra Narayan Sinha 4. Shrimati Jayaben Vajubhai Shah 5. Shri Radha Charan Sharma 6. Shri C. R. Narasimhan 7. Shri R. Govindarajulu Naidu 8. Shri T. R. Neswi 9. Shri Hiralal Shastri 10. Shri Tribhuan Narayan Singh 11. Shri Sinhasan Singh 12. Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee 13. Pandit Munishwar Dutt Upadhyay 14. Shri Birbal Singh 15. Pandit Krishna Chandra Sharma 16. Shri Nardeo Snatak 17. Shri Mahavir Tyagi 18. Shri N. G. Ranga 19. Shri N. R. Ghosh 20. Shri Nibaran Chandra Laskar 21. Shri T. Sanganna 22. Shri Prakash Vir Shastri 23. Shri Prabhat Kar 24. Shri T. Nagi Reddy 25. Shri Braj Raj Singh 26. Shri J. M. Mohamed Imam 27. -

1 AIMS MEMBER INSTITUTIONS North Zone CHANDIGARH Prof

AIMS MEMBER INSTITUTIONS North Zone CHANDIGARH Prof Deepak Kapoor Dean AIMS/AN/CH/NZ/1001 University Business School Punjab University, Chandigarh - 160014 Tel: 0172 - 2541591, 2534701, Mob: 9417006837, Fax: 0172 - 2541591 Email: [email protected], [email protected], Web: http://ubs.puchd.ac.in/ Prof Bhagat Ram Dean AIMS/LF/CH/NZ/2123 ICFAI Business School B 101, Industrial Area, SAS Nagar Phase - 8, Mohali - 160059 Chandigarh Tel: 0172 - 5063547-49 Fax: 0172 - 50635444 Email: [email protected], Website: www.ibsindia.org DELHI Mr Gautam Thapar President AIMS/LF/DLI/NZ/2197 All India Management Association Centre for Management Education "Management House", 14 Institutional Area, Lodhi Road, New Delhi - 110 003 Tel: 011-24645100, 24617354, 43128100, Fax: 011-24626689, Email: [email protected], Website: www.aima-ind.org Mr Raj Kumar Jain Chairman AIMS/AN/DL/NZ/1368 APAR Indian College of Management and Technology Apar Campus, 6 Community Centre, Sector – 8, Rohini 1 Delhi – 110 085 Tel: 011 – 45044000 Email: [email protected] Website: www.aparindiacollege.com Dr Alok Saklani Director AIMS/LF/DLI/NZ/2001 Apeejay School of Management Sector - 8, Dwarka Institutional Area, New Delhi - 110 077 Tel: 011- 25363979/80/83/86/88, 25364523 Fax: 011-25363985 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.apeejay.edu Dr A N Sarkar Director AIMS/AN/DLI/NZ/1003 Asia-Pacific Institute of Management Plot No: 3 & 4, Institutional Area, Jasola (Opp Sarita Vihar), New Delhi - 110025 Tel: 011 - 42094800 (30 Lines), 011-26950549, 25363978 Fax: 011 - 26951541 E-Mail: -

English Version

htb Series, Vol. V!!. No.1 Tuesday, July 23, 1985 SravanB 1, 1907 (Saka) LOK SABHA DEBA1L.. (English Version) Third Session (Eighth Lok Sabba) (Vol. VII contains Nos. 1 to 10) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price: Rs. 4.00 [ORIGINAL ENGLISH PROCEEDINGS INClUDFD IN ENGLISh VEIlSION AND OR.IGINAL HINDI PllOcBEDINOS INDCLUDED IN HINDI VI1\SION WILL BB TUATID AS AUTHOlUTATIVE AND NOT THE TIlANSLAnON TJIIUOP.] CONTENTS No.1, Tuelday, July 23, 1985/Sravana 1, 1907 (Saka) CoLUMNS Mcmberswom I Obituary References 1-7 Oral Answer to Questions ·Starred Questions Nos. 1 to 5 7-26 Written Answers to Questions: Starred Questions Nos. 6 to 20 26-38 Unstarred Questions Nos. 1 to 10, 12 to 72, 38-230 74 to 159 and 161 to 214. Re : Adjournment Motion on Proclaiming Eemergency 231-253 Papers Laid on the Table 252-253 Statement Re : (i) Collision of 138 UP Amritsar-Bilaspu.r Chhatis garh Express with Down Tugblalcabad goods train at Raja-Ki Mandi station of Central Railway on 13.6.1985; and (ii) Collision of a private bus with a goods train at' a manned level crossing gate between Dr. Radhakrishnan Nagar and Morwani Stations of Western Railway on 16.6.1985 Shri Bansi Lal 253-256 ~tatement Re: Crash of Air India Jumbo Jet 'KANISHKA' on 23rd June, 1985 Shri Asbok Gehlot 256-258 The Sign+marked above the name of a Member indicates the Question was a«ually asked on the floor of the House b)' that Member. (U) CoLUMNS Statement Re : Report of rthe National Institute of Public Finance and Policy on "Aspects of black Economy in India" Shri Vish wanath Pratap Singh 258-259 Calling Attention to Matter of Urgent Public Importance- 259-285 Armed clashes on Assam-Nagaland border between Assam Police and NagaJand Police Shri Lalit Maken 259-260 263-268 Shri S.B. -

District Health Plan 2010-2011

District Health Plan 2010-2011 District Health Society, Gaya 1 Foreword NRHM was launched in April 2005. The State Health Society (Bihar) and the District Health Societies (Gaya) were formed by end of 2005. The recruitment of Block level managers and other staff were completed by May 2007. The data centre was established by 2006, which worked on outsourced mode. However, a new system replaced the out sourced mode and the data centres were put in place by 2008. Public health system has witnessed an increased utilization of services in 2009 reflected by an increased number of persons being provided every type of service that is available- be it outpatient care, inpatient care, institutional delivery services or emergency services, or surgical services, or laboratory services. The strategy of revitalizing the BPHC and District hospital has shown results. Human resources and Quality of services remains an issue that needs to be addressed. The District Health Planning in Gaya used a situational analysis form focusing on areas in health covered by NRHM viz; RCH, NRHM Additionalities, Immunization, Disease control, and Convergence. This DHAP has been evolved through a participatory and consultative process, wherein community, NGO and other stakeholders have participated and deliberated on the specific health needs. I need to congratulate the SHS Bihar for its dynamic leadership and enthusiasm provided to district level so that the plan is made. We also acknowledge PHRN (NGO partner) for organizing the capacity building programme for the preparation of District Health Action Plan. This District Health Action Plan (DHAP) is one of the key instruments to achieve NRHM goals. -

Request for Proposal(Rfp)For Selection of Agency for Advertisement Rights

(A Constituent Unit of Patliputra University, Patna) Grade - 'A' Accredited by NAAC C.P.E. Status by U.G.C. REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL(RFP) FOR SELECTION OF AGENCY FOR ADVERTISEMENT RIGHTS ON HOARDINGS AT COLLEGE CAMPUS , PATNA At Principal , A.N College Boring Road ,Patna Email : [email protected] Website : www.ancpatna.ac.in Selection of Agency for advertisement rights on hoardings at College Campus, Patna Disclaimer 1. Though adequate care has been taken while preparing the RFP document, the Bidders/Applicants shall satisfy them that the document is complete in all respects. Intimation of any discrepancy shall be given to this office immediately. If no intimation is received from any Bidder within fifteen (15) days from the date of notification of RFP /Issue of the RFP documents, it shall be considered that the RFP document is complete in all respects and has been received by the Bidder. 2. Authority reserves the right to modify, amend or supplement this RFP document including all formats and Annexure. Any such change would be communicated to the applicants by posting it on the website www.ancpatna.ac.in. 3. The information provided in this RFP not intended to be an exhaustive on account of statutory requirements and should not be regarded as a complete or authoritative statement of law. The Authority accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or otherwise for any interpretation or opinion on the law expressed herein. 4. The Authority, its employees and advisers make no representation or warranty and shall have no liability to any person including any Applicant under any law, statute, rules or regulations or tort, principles of restitution or unjust enrichment or otherwise for any loss, damages, cost or expense which may arise from or be incurred or suffered on account of anything contained in this RFP or otherwise, including the accuracy, adequacy, correctness, reliability or completeness of the RFP and any assessment, assumption, statement or information contained therein or deemed to form part of this RFP or arising in anyway in this subject. -

Bihar Muslims' Response to Two Nation Theory 1940-47

BIHAR MUSLIMS' RESPONSE TO TWO NATION THEORY 1940-47 ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bortor of IN HISTORY BY MOHAMMAD SAJJAD UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. RAJ KUNAR TRIVEDI CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTOFflC AUGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2003 ABSTRACT Bihar Muslims' Response to Two Nation Theory 1940-47: The Lahore session (1940) of the Muslim League adopted a resolution in which Muslim majority areas were sought to be grouped as "autonomous and sovereign" , 'independent states". This vaguely worded resolution came to be known as Pakistan resolution. The Muslim League, from its days of foundation (in 1906) to the provincial elections of 1937, underwent many changes. However, after the elections of 1937 its desperation had increased manifold. During the period of the Congress ministry (1937-39), the League succeeded in winning over a sizeable section of the Muslims, more particularly the landed elites and educated middle class Muslims of Muslim minority provinces like U.P. and Bihar. From 1937 onwards, the divide between the two communities went on widening. Through a massive propaganda and tactful mobilizations, the League expanded its base, adopted a divisive resolution at Lahore (1940) and then on kept pushing its agenda which culminated into the partition of India. Nevertheless, the role of imperialism, the role of Hindu majoritarian organizations like the Hindu Mahasabha and tactical failure on the part of the Congress combined with communalization of the lower units of the Congress (notwithstanding the unifying ideals of the Congress working Committee) can not be denied in the partition of the country. -

Hon' Ble Dy Chief Minister of Bihar- Shri Shushil Kumar Modi

Hon' ble Dy Chief Minister of Bihar- Shri Shushil Kumar Modi Profile of the Dy CM Sushil Kumar Modi was born on the 5th of January, 1952 to Late Shri Moti Lal Modi and Late Smt. Ratna Devi. He started his schooling with Mount Caramel School, Patna where he did his Upper and Lower KG and also Class 1. In St Michaels’ High School, Patna he completed Class 2 and 3 and then joined St Severin’s High School for Class 4th to 6th. He then joined Ram Mohan Roy Seminary for his final schooling i.e. 8th to 10th. It is noteworthy that Mr Modi was a bright student from the start and throughout his school life he secured 1st division. He did his pre-university from Commerce College, Patna and B.Sc. from B.N.College, Patna with a 1st Division. He graduated from the state’s premier institution Patna Science College, Patna University and did his Botany Hons in 1973 securing 2nd position in the whole University. He was a proud scholar and holder of the National Merit Scholarship for Academic Excellence. To pursue his academic career further he enrolled himself in the M.Sc Botany Course in Patna University, but elsewhere lay his calling and as Shri Jai Prakash Narayan called on the young, zealous students from Bihar to make a change in society, he decided to participate in the movement and left College for a year. But who knew that it was the last of his College days and his first of steps into the world of public welfare and politics.