Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Governance and Development in India a Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar After 1990

RUPRECHT-KARLS-UNIVERSITÄT HEIDELBERG FAKULTÄT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTS-UND SOZIALWISSENSCHAFTEN Dynamics of Governance and Development in India A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after 1990 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. rer. pol. an der Fakultät für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Erstgutachter: Professor Subrata K. Mitra, Ph.D. (Rochester) Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Dietmar Rothermund vorgelegt von: Seyedhossein Zarhani Dezember 2015 Acknowledgement The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help of many individuals. I am grateful to all those who have provided encouragement and support during the whole doctoral process, both learning and writing. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Subrata K. Mitra, for his guidance and continued confidence in my work throughout my doctoral study. I could not have reached this stage without his continuous and warm-hearted support. I would especially thank Professor Mitra for his inspiring advice and detailed comments on my research. I have learned a lot from him. I am also thankful to my second supervisor Professor Ditmar Rothermund, who gave me many valuable suggestions at different stages of my research. Moreover, I would also like to thank Professor Markus Pohlmann and Professor Reimut Zohlnhöfer for serving as my examination commission members even at hardship. I also want to thank them for letting my defense be an enjoyable moment, and for their brilliant comments and suggestions. Special thanks also go to my dear friends and colleagues in the department of political science, South Asia Institute. My research has profited much from their feedback on several occasions, and I will always remember the inspiring intellectual exchange in this interdisciplinary environment. -

STATISTICAL REPORT GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 the 14Th LOK SABHA

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 TO THE 14th LOK SABHA VOLUME III (DETAILS FOR ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME III (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 6 2. Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies 7 - 1332 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES 7 . AC Arunachal Congress 8 . ADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 9 . AGP Asom Gana Parishad 10 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 11 . AITC All India Trinamool Congress 12 . BJD Biju Janata Dal 13 . CPI(ML)(L) Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (Liberation) 14 . DMK Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 15 . FPM Federal Party of Manipur 16 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 17 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 18 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 19 . JKN Jammu & Kashmir National Conference 20 . JKNPP Jammu & Kashmir National Panthers Party 21 . JKPDP Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party 22 . JMM Jharkhand Mukti Morcha 23 . KEC Kerala Congress 24 . KEC(M) Kerala Congress (M) 25 . MAG Maharashtrawadi Gomantak 26 . MDMK Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 27 . MNF Mizo National Front 28 . MPP Manipur People's Party 29 . MUL Muslim League Kerala State Committee 30 . -

Linguistic Survey of India Bihar

LINGUISTIC SURVEY OF INDIA BIHAR 2020 LANGUAGE DIVISION OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA i CONTENTS Pages Foreword iii-iv Preface v-vii Acknowledgements viii List of Abbreviations ix-xi List of Phonetic Symbols xii-xiii List of Maps xiv Introduction R. Nakkeerar 1-61 Languages Hindi S.P. Ahirwal 62-143 Maithili S. Boopathy & 144-222 Sibasis Mukherjee Urdu S.S. Bhattacharya 223-292 Mother Tongues Bhojpuri J. Rajathi & 293-407 P. Perumalsamy Kurmali Thar Tapati Ghosh 408-476 Magadhi/ Magahi Balaram Prasad & 477-575 Sibasis Mukherjee Surjapuri S.P. Srivastava & 576-649 P. Perumalsamy Comparative Lexicon of 3 Languages & 650-674 4 Mother Tongues ii FOREWORD Since Linguistic Survey of India was published in 1930, a lot of changes have taken place with respect to the language situation in India. Though individual language wise surveys have been done in large number, however state wise survey of languages of India has not taken place. The main reason is that such a survey project requires large manpower and financial support. Linguistic Survey of India opens up new avenues for language studies and adds successfully to the linguistic profile of the state. In view of its relevance in academic life, the Office of the Registrar General, India, Language Division, has taken up the Linguistic Survey of India as an ongoing project of Government of India. It gives me immense pleasure in presenting LSI- Bihar volume. The present volume devoted to the state of Bihar has the description of three languages namely Hindi, Maithili, Urdu along with four Mother Tongues namely Bhojpuri, Kurmali Thar, Magadhi/ Magahi, Surjapuri. -

Inter-Dist Movement Allowed After 3 Months, Curfew Relaxedby an Hour

EasternChroniWINDOW TO THE EAST cle WEATHERWATCH TALIBAN ANNOUNCE ‘amnesty’ NIA ARRESTS 2 KERALA BOWLERS SHINE WITH BAT Max 28°c across Afghanistan, urge women, one traveled to Tehran too as India beat England by 151 Min 25°c women to join govt P 6 to join IS in Syria P 2 runs P 12 Humidity 88% VOL XI, ISSUE 490 PUBLISHED SIMULTANEOUSLY FROM SILCHAR GUWAHATI KOLKATA PAGES: 10 epaper at: www.easternchronicle.net PRICE `9 WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 18, 2021 TENSION ALONG MIZORAM-ASSAM BORDER ESCALATE AGAIN Inter-dist movement allowed after 3 Assam police allegedly months, curfew relaxed by an hour shoot at Mizo civilians CNS & AGENCIES to another. THE ASSAM GOVERNMENT HAS ALLOWED INTER- CHRONICLE NEWS SERVICE The new SOP reduces the GUWAHATI: The Assam govern- present curfew timings of 6pm › DISTRICT MOVEMENT OF PRIVATE VEHICLES BARRING AIZAWL: Tension along the ment on Tuesday decided to to 5am daily to 7pm-5am daily. TO AND FROM KAMRUP (METROPOLITAN) DISTRICT Mizoram-Assam border esca- lift restrictions on inter-district “Meetings or gatherings in open AND OFFLINE CLASSES IN HIGHER EDUCATIONAL lated again on Tuesday when movement of vehicles. The spaces would be allowed for up to personnel of Assam police curbs were put in place three 200 persons. In closed spaces, 50% INSTITUTES WITH FULLY VACCINATED STUDENTS BESIDES guarding the border have months ago to contain the of the hall’s capacity or 200 fully WITHDRAWING THE ODD-EVEN SYSTEM FOR VEHICLES. allegedly shot at three civil- spread of coronavirus. vaccinated persons (whichever ians, including two women, The new direction, which will is lower) will be allowed to hold continue to remain closed. -

Chapter-1 Introduction 1. Introduction

CHAPTER-1 INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION Education, in the broad sense, means preparation for life, it aims at all round development of individuals. Thus education is concerned with developing optimum organic health and emotional vitality such as social consciousness, acquisition of knowledge, wholesome attitude, moral and spiritual qualities.1 Education is also considered a process by which, individual is shaped to fit into the society to maintain and advance the social order. It is a system designed to make an individual rational, mature and a knowledgeable human being. Education is the modification of behaviour of an individual for the better adjustment in the society and for making a useful and worthwhile citizen. 2 The pragmatic view of education highlights learning by doing. Learning by doing takes place in the class room, in the library, on the play ground, in the gymnasium, or on the trips at home. 3 Civilized societies have always felt the need for physical education for its members except during the middle ages, when physical education as is typically known today found almost no place within the major educational pattern that prevailed. During the period, in Europe, asceticism in the early Christian church on the other hand set a premium on physical weakness in the vain hope that this was the path to spiritual excellence.4 During the middle age sports was associated with military motives, since many of the physical activities were designed to harden and strengthen man for combat5. The rapid development of physical education within the present century and the weighted influence accruing to some of its more spectacular activities suggest the imperative need, a clean understanding of unequal role, a well balanced programme in the field may give rise to the optimum growth and development of the youth. -

Hazaribagh, District Census Handbook, Bihar

~ i ~ € :I ':~ k f ~ it ~ f !' ... (;) ,; S2 ~'" VI i ~ ~ ~ ~ -I fI-~;'~ci'o ;lO 0 ~~i~~s. R m J:: Ov c V\ ~ -I Z VI I ~ =i <; » -< HUm N 3: ~: ;;; » ...< . ~ » ~ :0: OJ ;: . » " ~" ;;; C'l ;!; I if G' l C!l » I I .il" '" (- l' C. Z (5 < ..,0 :a -1 -I ~ o 3 D {If J<' > o - g- .,. ., ! ~ ~ J /y ~ ::.,. '"o " c z '"0 3 .,.::t .. .. • -1 .,. ... ~ '" '"c ~ 0 '!. s~ 0 c "v -; '"z ~ a 11 ¥ -'I ~~ 11 CENSUS 1961 BIHAR DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 14 HAZARIBAGH PART I-INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CENSUS TABLES AND OFFICIAL STATISTICS -::-_'" ---..... ..)t:' ,'t" -r;~ '\ ....,.-. --~--~ - .... .._,. , . /" • <":'?¥~" ' \ ........ ~ '-.. "III' ,_ _ _. ~ ~~!_~--- w , '::_- '~'~. s. D. PRASAD 0 .. THE IlQ)IAJr AD:uJlIfISTBA'X'lVB SEBVlOE Supwtnundent 01 Oen.ua Operatio1N, B'h4r 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, BIHAR (All the Census Publications of this State will bear Vol. no. IV) Central Government Publications PART I-A General Report PART I-B Report on Vital Statistics of Bihar, 1951-60 PART I-C Subsidiary Tables of 1961. PART II-A General Population Tables· PART II-B(i) Economic Tables (B-1 to B-IV and B-VU)· PAR't II-B(ii) Economic Tables (B-V, B-VI, B-VIII and B-IX)* PART II-C Social and Cultural Tables* PART II-D Migration Tables· PART III (i) Household Economic Tables (B-X to B-XIV)* PART III (ii) Household Economic Tables (B-XV to B-XVII)* PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments· PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Table:,* PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribe&* PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Surveys •• (Monoglaphs on 37 selected villages) PART VII-A Selected Crafts of Bihar PART VII-B Fairs and Festivals of Bihar PART VIII-A Administration Report on Enumeration * } (Not for sale) PART VIII-B Administration Report on Tabulation PART IX Census Atlas of Bihar. -

Indo-Caribbean "Local Classical Music"

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2000 The Construction of a Diasporic Tradition: Indo-Caribbean "Local Classical Music" Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/335 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] VOL. 44, NO. 1 ETHNOMUSICOLOGY WINTER 2000 The Construction of a Diasporic Tradition: Indo-Caribbean "Local Classical Music" PETER MANUEL / John Jay College and City University of New York Graduate Center You take a capsule from India leave it here for a hundred years, and this is what you get. Mangal Patasar n recent years the study of diaspora cultures, and of the role of music therein, has acquired a fresh salience, in accordance with the contem- porary intensification of mass migration and globalization in general. While current scholarship reflects a greater interest in hybridity and syncretism than in retentions, the study of neo-traditional arts in diasporic societies may still provide significant insights into the dynamics of cultural change. In this article I explore such dynamics as operant in a unique and sophisticated music genre of East Indians in the Caribbean.1 This genre, called "tan-sing- ing," has largely resisted syncretism and creolization, while at the same time coming to differ dramatically from its musical ancestors in India. Although idiosyncratically shaped by the specific circumstances of the Indo-Caribbean diaspora, tan-singing has evolved as an endogenous product of a particu- lar configuration of Indian cultural sources and influences. -

General Elections, 1977 to the Sixth Lok Sabha

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1977 TO THE SIXTH LOK SABHA VOLUME I (NATIONAL AND STATE ABSTRACTS & DETAILED RESULTS) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI ECI-GE77-LS (VOL. I) © Election Commision of India, 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without prior and express permission in writing from Election Commision of India. First published 1978 Published by Election Commision of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi - 110 001. Computer Data Processing and Laser Printing of Reports by Statistics and Information System Division, Election Commision of India. Election Commission of India – General Elections, 1977 (6th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME I (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 2 2. Number and Types of Constituencies 3 3. Size of Electorate 4 4. Voter Turnout and Polling Station 5 5. Number of Candidates per Constituency 6 - 7 6. Number of Candidates and Forfeiture of Deposits 8 7. Candidates Data Summary 9 - 39 8. Electors Data Summary 40 - 70 9. List of Successful Candidates 71 - 84 10. Performance of National Parties vis-à-vis Others 85 11. Seats won by Parties in States / UT’s 86 - 88 12. Seats won in States / UT’s by Parties 89 - 92 13. Votes Polled by Parties – National Summary 93 - 95 14. Votes Polled by Parties in States / UT’s 96 - 102 15. Votes Polled in States / UT by Parties 103 - 109 16. Women’s Participation in Polls 110 17. -

The Politics of Inequality Competition and Control in an Indian Village

Asian Studies at Hawaii, No. 22 The Politics of Inequality Competition and Control in an Indian Village Miriam Sharma ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAM UNIVERSITY OF HAWAll THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF HAWAII Copyright © 1978 by The University Press of Hawaii All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States ofAmerica Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Sharma, Miriam, 1941 The politics ofinequality. (Asian studies at Hawaii; no. 22) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Villages-India-Case studies. 2. Local govern ment-India-Case studies. 3. India-Rural conditions -Case studies. 4. Caste-India-Case studies. I. Title. II. Series. DS3.A2A82 no. 22 [HV683.5] 950'.08s ISBN 0-8248-0569-0 [301.5'92'09542] 78-5526 All photographs are by the author Map 1by Iris Shinohara The Politics of Inequality - To the people ofArunpur and Jagdish, Arun, and Nitasha: for the goodness they have shared with me Contents LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS X LIsT OF TABLES xiii PREFACE xv CHAPTER 1 POLITICS IN INDIAN VILLAGE SOCIETY 3 Politics in Arunpur 5 The Dialectic 8 Fieldwork and the Collection of Data 12 CHAPTER 2 THE VILLAGE OF ARUNPUR 19 Locale ofArunpur 21 Village History 24 Water, Land, and Labor in the Agricultural Cycle of Arunpur 28 Traditional Mode of Conflict Resolution: The Panchayat 37 The Distribution of Resources in Arunpur 40 CHAPTER 3 ARUNPUR AND THE OUTSIDE WORLD: THE EXTENSION OF GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION 49 Extension ofGovernment Administration 49 New Alternatives for Conflict Resolution 53 New Resources and Relationships with Government Personnel -

“Everyone Has Been Silenced”; Police

EVERYONE HAS BEEN SILENCED Police Excesses Against Anti-CAA Protesters In Uttar Pradesh, And The Post-violence Reprisal Citizens Against Hate Citizens against Hate (CAH) is a Delhi-based collective of individuals and groups committed to a democratic, secular and caring India. It is an open collective, with members drawn from a wide range of backgrounds who are concerned about the growing hold of exclusionary tendencies in society, and the weakening of rule of law and justice institutions. CAH was formed in 2017, in response to the rising trend of hate mobilisation and crimes, specifically the surge in cases of lynching and vigilante violence, to document violations, provide victim support and engage with institutions for improved justice and policy reforms. From 2018, CAH has also been working with those affected by NRC process in Assam, documenting exclusions, building local networks, and providing practical help to victims in making claims to rights. Throughout, we have also worked on other forms of violations – hate speech, sexual violence and state violence, among others in Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Bihar and beyond. Our approach to addressing the justice challenge facing particularly vulnerable communities is through research, outreach and advocacy; and to provide practical help to survivors in their struggles, also nurturing them to become agents of change. This citizens’ report on police excesses against anti-CAA protesters in Uttar Pradesh is the joint effort of a team of CAH made up of human rights experts, defenders and lawyers. Members of the research, writing and advocacy team included (in alphabetical order) Abhimanyu Suresh, Adeela Firdous, Aiman Khan, Anshu Kapoor, Devika Prasad, Fawaz Shaheen, Ghazala Jamil, Mohammad Ghufran, Guneet Ahuja, Mangla Verma, Misbah Reshi, Nidhi Suresh, Parijata Banerjee, Rehan Khan, Sajjad Hassan, Salim Ansari, Sharib Ali, Sneha Chandna, Talha Rahman and Vipul Kumar. -

2021010446.Pdf

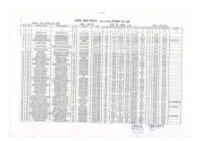

SHIKSHAK NIYOJAN 2019 UCHAKAGAON (GOPALGANJ) Provisional Merit List of 1 to 5 Primary School Year 2019, Sub:- General TOTAL REMARK SNO FNO NAME FATHER'S NAME ADDRESS D.O.B CAT MATRIC INTER B.ED. M. TOTAL TET MERIT S 1 2238 JAVED ALI ALAUDDIN ALI KUSHINAGAR (UP) 3-Apr-1997 UR 95 82.8 85.85 87.88 6 93.88 2 1729 JULI TIWARI BIRJESH TIWARI GORKHPUR 15.06.1996 URF 95 84 88.15 89.05 2 91.05 3 2182 IRFAN ANSARI NUROOL HUQUE ANSARI P.CHAMPARAN 7-Aug-1999 EBC 87.67 91.8 87.07 88.85 2 90.85 4 1240 VIKASH KUMAR BIJENDRA SINGH GOPALGANJ 24.08.1992 BC 90.4 87.4 86.08 87.96 2 89.96 5 620 RITESH MISHRA SATISH MISHRA KUSHINAGAR 12.05.1996 UR 77 92 87.5 85.50 4 89.50 6 1304 ANMOL PANDIT SAT NARAYIN PANDIT SIWAN 15.04.1987 EBC 85.83 86 84.59 85.47 4 89.47 7 364 A PRITI SINGH SURENDRA SINGH GOPALGANJ 11.11.1996 BCF 79 85.6 90.6 85.07 4 89.07 8 1943 SUSHMITA JAISWAL TIRPURARI JAISWAL GORKHPUR 10.02.1996 URF 81.5 88.8 90.12 86.81 2 88.81 9 2284 KUMAR ABHIMANYU BIRENDRA MISHRA GOPALGANJ 20-Oct-1999 EWS 82 87 85 84.67 4 88.67 10 1924 BAIBHAV KUMAR MISHRA HARIDAR MISHRA GORAKHPUR 30.12.1996 UR 89.3 77 87.68 84.66 4 88.66 11 1940 SHATURADHAN PATEL RAM NIWAS SINGH MAU 30.12.1995 UR 89.3 78.6 90.84 86.25 2 88.25 12 1239 AMITESH KUMAR DINANATH PRASAD SIWAN 13.11.1992 BC 87.6 88.4 87.66 87.89 0 87.89 13 1259 BALIRAM YADAV RAJENDRA YADAV BAKSAR 08.07.1983 BC 85.33 87.6 90 87.64 0 87.64 14 2132 GIRIJA SHANKAR YADAV RAMESH YADAV DEORIA (UP) 1-Jun-1996 UR 84 83.4 89.53 85.64 2 87.64 15 1913 RAJAT KUMAR NAND KISHOR PRASAD MAHARAJGANJ 14.08.1995 UR 79.8 90.8 86.06 85.55 -

Compliance Or Defiance? the Case of Dalits and Mahadalits

Kunnath, Compliance or defiance? COMPLIANCE OR DEFIANCE? THE CASE OF DALITS AND MAHADALITS GEORGE KUNNATH Introduction Dalits, who remain at the bottom of the Indian caste hierarchy, have resisted social and economic inequalities in various ways throughout their history.1 Their struggles have sometimes taken the form of the rejection of Hinduism in favour of other religions. Some Dalit groups have formed caste-based political parties and socio-religious movements to counter upper-caste domination. These caste-based organizations have been at the forefront of mobilizing Dalit communities in securing greater benefits from the Indian state’s affirmative action programmes. In recent times, Dalit organizations have also taken to international lobbying and networking to create wider platforms for the promotion of Dalit human rights and development. Along with protest against the caste system, Dalit history is also characterized by accommodation and compliance with Brahmanical values. The everyday Dalit world is replete with stories of Dalit communities consciously or unconsciously adopting upper-caste beliefs and practices. They seem to internalize the negative images and representations of themselves and their castes that are held and propagated by the dominant groups. Dalits are also internally divided by caste, with hierarchical rankings. They themselves thus often seem to reinforce and even reproduce the same system and norms that oppress them. This article engages with both compliance and defiance by Dalit communities. Both these concepts are central to any engagement with populations living in the context of oppression and inequality. Debates in gender studies, colonial histories and subaltern studies have engaged with the simultaneous existence of these contradictory processes.