Breeding Birds of the Unicoi Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hiking 34 Mountain Biking 37 Bird Watching 38 Hunting 38 Horseback Riding 38 Rock Climbing 40 Gliding 40 Watersports 41 Shopping 44 Antiquing 45 Craft Hunting 45

dventure Guide to the Great Smoky Mountains 2nd Edition Blair Howard HUNTER HUNTER PUBLISHING, INC. 130 Campus Drive Edison, NJ 08818-7816 % 732-225-1900 / 800-255-0343 / fax 732-417-1744 Web site: www.hunterpublishing.com E-mail: [email protected] IN CANADA: Ulysses Travel Publications 4176 Saint-Denis, Montréal, Québec Canada H2W 2M5 % 514-843-9882 ext. 2232 / fax 514-843-9448 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: Windsor Books International The Boundary, Wheatley Road, Garsington Oxford, OX44 9EJ England % 01865-361122 / fax 01865-361133 ISBN 1-55650-905-7 © 2001 Blair Howard All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, elec- tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. This guide focuses on recreational activities. As all such activities contain elements of risk, the publisher, author, affiliated individuals and compa- nies disclaim any responsibility for any injury, harm, or illness that may occur to anyone through, or by use of, the information in this book. Every effort was made to insure the accuracy of information in this book, but the publisher and author do not assume, and hereby disclaim, any liability or any loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misleading information or potential travel problems caused by this guide, even if such errors or omis- sions result from negligence, accident or any other cause. Cover photo by Michael H. Francis Maps by Kim André, © 2001 Hunter -

Biological Evaluation

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service March 2018 Biological Evaluation Prospect Hamby Project Tusquitee Ranger District, Nantahala National Forest Cherokee County, North Carolina For Additional Information Contact: Tusquitee Ranger District 123 Woodland Drive Murphy, North Carolina 28906 (828) 837-5152 2-1 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Proposed Action ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Species Considered ..................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 PROPOSED, ENDANGERED, and THREATENED SPECIES ................................................... 3 2.1 Aquatic Resources ...................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Botanical Resources ................................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Wildlife Resources ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.4 Effects Determinations for Proposed, Endangered, and Threatened Species ........................... 14 3.0 SENSITIVE SPECIES ................................................................................................................. 14 3.1 Aquatic -

Public Law 88-577, September 3, 1964) and Related Acts, the U.S

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MISCELLANEOUS FIELD STUDIES UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP MF-1587-C PAMPHLET MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF THE SNOWBIRD ROADLESS AREA GRAHAM COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA By Frank G. Lesure, U.S. Geological Survey and Mark L. Chatman, U.S. Bureau of Mines 1983 Studies Related to Wilderness Under the provisions of the Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577, September 3, 1964) and related acts, the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines have been conducting mineral surveys of wilderness and primitive areas. Areas officially designated as "wilderness," "wild," or "canoe" when the act was passed were incorporated into the National Wilderness Preservation System, and some of them are presently being studied. The act provided that areas under consideration for wilderness designation should be studied for suitability for incorporation into the Wilderness System. The mineral surveys constitute one aspect of the suitability studies. The act directs that the results of such surveys are to be made available to the public and be submitted to the President and the Congress. This report discusses the results of a mineral survey of the Snowbird Roadless Area (08-061), Nantahala National Forest, Graham County, North Carolina. The area was classified as a further planning area during the Second Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE II) by the U.S. Forest Service, January 1979. MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL SUMMARY STATEMENT The Snowbird Roadless Area includes 8490 acres of rugged wooded terrain in the Nantahala National Forest, Graham County, N. C. The area is underlain by folded metasedimentary rocks of the Great Smoky Group of Late Proterozoic age, and has a low potential for mineral resources. -

Fort Harry: a Phenomenon in the Great Smoky Mountains

The Blount Journal, Fall 2003 FORT HARRY: A PHENOMENON IN THE GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK Submitted By Pete Prince, author of ©Ghost Towns in the Great Smokies Seasoned hikers in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park claim echoes of the Cherokee Indians are still heard at the site of the old Civil War fortification within the Park, yet ten million tourists annually drive through the site of Fort Harry unaware such a place ever existed. The site of this historical fort is unmarked and unnoticed on a main highway in the nation's most visited park. Fort Harry, a Confederate fort, was built in 1862 by Cherokee Confederate troops and white Highlanders. The fort was to prevent Federal forces from Knoxville and East Tennessee from destroying the Alum Cave Mines on the side of Mount LeConte which provided gunpowder and chemicals for the Confederacy. Built on a bluff. Fort Harry looked straight down on the Old Indian Road leading to Indian Gap, the Oconaluftee Turnpike and Western North Carolina. The Federal troops did raid Western North Carolina but it was by way of Newport, Asbury Trail, Mount Sterling, Cataloochee, Waynesville and Oconalufree. Fort Harry was at the 3300-foot elevation of the Great Smoky Mountains eight miles south of Gatlinburg, TN. The Confederate army confiscated the Sugarlands farm of Steve Cole for Fort Harry. Cole Creek is nearby. Fort Harry was on a ridge on West Prong Little Pigeon River .03 mile south of today's intersection of Road Prong and Walker Camp Prong. The fort site is on ^ewfound Gap Road 6.0 miles south of the Sugarlands Visitor Center at Gatlinburg dnd 0.5 miles north of the first tunnel at the Chimney Tops parking area on Newfound Gap Road. -

Comments on the U.S. Forest Service's Nantahala and Pisgah

Comments on the U.S. Forest Service’s Nantahala and Pisgah National Forest Proposed Land Management Plan By Donald W. Hyatt - Potomac Valley Chapter ARS http://www.arspvc.org/newsletter.html Introduction The U.S. Forest Service has proposed a Land Management Plan for the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests that will guide their actions for the next 15 years. Having studied this 283-page document carefully the past few weeks and having read other related research, I do have concerns. In this article, I will share my thoughts about preserving the beauty and diversity of this spectacular region. These two National Forests cover over a million acres of forest land and some of the best displays of rhododendrons, azaleas, kalmia, and wildflowers in the Southern Appalachians. It includes Roan Mountain, Mount Mitchell, Grandfather Mountain, the Linville Gorge, and Hooper Bald just to name a few. The plan does not include Gregory Bald since it is in the nearby Great Smoky Mountains National Park and not part of the National Forests. Overview The following four headings summarize my main points but I will explain those assertions in greater detail later in the discussion portion of this document. 1. Biodiversity and Endangered Species Although the plan claims to be addressing biodiversity and rare species, I feel that some of the assumptions are simplistic. The Southern Appalachians have an extremely rich ecosystem. Besides the eighteen Federally endangered species referenced by the document, there are many other unique plant and animal communities in those forest lands that seem to be ignored. Many are quite rare and could be threatened even though they may not have made the endangered species list. -

Introduction to the Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan

SOUTHERN BLUE RIDGE ECOREGIONAL CONSERVATION PLAN Summary and Implementation Document March 2000 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY and the SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN FOREST COALITION Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan Summary and Implementation Document Citation: The Nature Conservancy and Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition. 2000. Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan: Summary and Implementation Document. The Nature Conservancy: Durham, North Carolina. This document was produced in partnership by the following three conservation organizations: The Nature Conservancy is a nonprofit conservation organization with the mission to preserve plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition is a nonprofit organization that works to preserve, protect, and pass on the irreplaceable heritage of the region’s National Forests and mountain landscapes. The Association for Biodiversity Information is an organization dedicated to providing information for protecting the diversity of life on Earth. ABI is an independent nonprofit organization created in collaboration with the Network of Natural Heritage Programs and Conservation Data Centers and The Nature Conservancy, and is a leading source of reliable information on species and ecosystems for use in conservation and land use planning. Photocredits: Robert D. Sutter, The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This first iteration of an ecoregional plan for the Southern Blue Ridge is a compendium of hypotheses on how to conserve species nearest extinction, rare and common natural communities and the rich and diverse biodiversity in the ecoregion. The plan identifies a portfolio of sites that is a vision for conservation action, enabling practitioners to set priorities among sites and develop site-specific and multi-site conservation strategies. -

Blue Ridge Parkway Long-Range Interpretive Plan Was Approved by Your Memorandum, Undated

6o/%. .G3/ . B LU E R IDG E PAR KWAY r . v BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE . ;HNICAL INFOR1uA1-!ON CENTER `VFR SERVICE CENTER Z*'K PARK SERVICE 2^/ C^QZ003 United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Harpers Ferry Center P.O. Box 50 IN REPLY REFER TO: Harpers Ferry, West Virginia 25425-0050 K1817(HFC-IP) BLRI 'JAN 3 0 2003 Memorandum To: Superintendent, Blue Ridge Parkway From: Associate Manager, Interpretive Planning, Harpers Ferry Center Subject: Distribution of Approved Long-Range Interpretive Plan for Blue Ridge Parkway The Blue Ridge Parkway Long-Range Interpretive Plan was approved by your memorandum, undated. All changes noted in the memorandum have been incorporated in this final document. Twenty bound copies are being sent to you with this memorandum, along with one unbound copy for your use in making additional copies as needed in the future. We have certainly appreciated the fine cooperation and help of your staff on this project. Enclosure (21) Copy to: Patty Lockamy, Chief of Interpretation bcc: HFC-Files HFC-Dailies HFC - Keith Morgan (5) HFC - Sam Vaughn HFC - Dixie Shackelford Corky Mayo, WASO HFC - John Demer HFC- Ben Miller HFC - Anne Tubiolo HFC-Library DSC-Technical Information Center K.Morgan/lmt/1-29-03 0 • LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY 2002 prepared by Department of the Interior National Park Service Blue Ridge Parkway Branch of Interpretation Harpers Ferry Center Interpretive Planning 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS M INTRODUCTION ..........................................1 BACKGROUND FOR PLANNING ...........................3 PARKWAY PURPOSE .......................................4 RESOURCE SIGNIFICANCE ................................5 THEMES ..................................................9 0 MISSION GOALS ......................................... -

Trail-Map-GSMNP-06-2014.Pdf

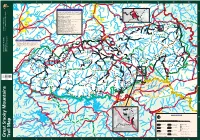

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 T E To Knoxville To Knoxville To Newport To Newport N N E SEVIERVILLE S 321 S E E 40 411 R 32 I V 441 E R r T 411 r Stream Crossings re e CHEROKEE NATIONAL FOREST r y Exit L T m a itt ) A le in m w r 443 a a k e Nearly all park trails cross small streams—making very wet crossings t 1.0 C t P r n n i i t a 129 g u w n P during flooding. The following trails that cross streams with no bridges e o 0.3 n i o M u r s d n ve e o se can be difficult and dangerous at flood stage. (Asterisks ** indicate the Ri ab o G M cl 0.4 r ( McGhee-Tyson L most difficult and potentially dangerous.) This list is not all-inclusive. e s ittl 441 ll Airport e w i n o Cosby h o 0.3 L ot e Beard Cane Trail near campsite #3 Fo Pig R R ive iv r Beech Gap Trail on Straight Fork Road er Cold Spring Gap Trail at Hazel Creek 0.2 W Eagle Creek Trail** 15 crossings e 0.3 0.4 SNOWBIRD s e Tr t Ridg L Fork Ridge Trail crossing of Deep Creek at junction with Deep Creek Trail en 0.4 o P 416 D w IN r e o k Forney Creek Trail** seven crossings G TENNESSEE TA n a nWEB a N g B p Gunter Fork Trail** five crossingsU S OUNTAIN 0.1 Exit 451 O M 32 Hannah Mountain Trail** justM before Abrams Falls Trail L i NORTH CAROLINA tt Jonas Creek Trail near Forney Creek le Little River Trail near campsite #30 PIGEON FORGE C 7.4 Long Hungry Ridge Trail both sides of campsite #92 Pig o 35 Davenport eo s MOUNTAIN n b mere MARYVILLE Lost Cove Trail near Lakeshore Trail junction y Cam r Trail Gap nt Waterville R Pittman u C 1.9 Meigs Creek Trail 18 crossings k i o h E v Big Creek E e M 1.0 e B W e Mt HO e Center 73 Mount s L Noland Creek Trail** both sides of campsite #62 r r 321 Hen Wallow Falls t 2.1 HI C r Cammerer n C Cammerer C r e u 321 1.2 e Panther Creek Trail at Middle Prong Trail junction 0.6 t e w Trail Br Tr k o L Pole Road Creek Trail near Deep Creek Trail M 6.6 2.3 321 a 34 321 il Rabbit Creek Trail at the Abrams Falls Trailhead d G ra Gatlinburg Welcome Center 5.8 d ab T National Park ServiceNational Park U.S. -

Tell-E-G Ra M Midw Eek March 8, 2016

POA Meetings and Events (red denotes irregularity of time, day, and/or location): Chat with the Public Relations Manager, 10 a.m.-2 p.m. Thursday, March 10, Welcome Center Golf Advisory Committee, 3 p.m. Thursday, March 10, POA Conference Room Finance Advisory Committee, 9 a.m. Friday, March 11, POA Conference Room Dock Captains, 3 p.m. Monday, March 14, POA Conference Room Public Works prepares Village for spring By Jeff Gagley, Director of Public Works If you have gone by the southern entrance lately, you may be curious what the crew is doing. We are adding a water feature to add interest. Meanwhile, we are also preparing the family beach for use as the weather warms. Gram - E - Tell Midweek MarchMidweek 8, 2016 TELLICO VILLAGE POA TELLICO VILLAGE POA TELL -E-GRAM Page 2 MIDWEEK MARCH 8, 2016 Internal Trails Committee members sought Are you interested in serving on the Internal Trails Committee? The Internal Trails Committee will be tasked with: Renovation of Existing Internal Trails Map current trails Create comprehensive publication identifying trails Create long-term marketing resource for existing trails Identify Improvement needs Create Trail Beautification Committee to spearhead the long term care for existing neighborhood trails Work with Public Works, Lions Club, and/or Boy Scouts to im- plement low cost improvements to existing trails Possibility for New Internal Trails Identify most desired location for additional trails and/or connecting trails Holly Bryant Possibly create a trails survey Review Greenway blueprints and identify most cost effective trail addi- tions based on their work Applications can be picked up at the Wellness Center or emailed beginning March 1 and must be returned to the Wellness Center by March 31. -

NATIONAL FORESTS /// the Southern Appalachians

NATIONAL FORESTS /// the Southern Appalachians NORTH CAROLINA SOUTH CAROLINA, TENNESSEE » » « « « GEORGIA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE National Forests in the Southern Appalachians UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE SOUTHERN REGION ATLANTA, GEORGIA MF-42 R.8 COVER PHOTO.—Lovely Lake Santeetlah in the iXantahala National Forest. In the misty Unicoi Mountains beyond the lake is located the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest. F-286647 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OEEICE WASHINGTON : 1940 F 386645 Power from national-forest waters: Streams whose watersheds are protected have a more even flow. I! Where Rivers Are Born Two GREAT ranges of mountains sweep southwestward through Ten nessee, the Carolinas, and Georgia. Centering largely in these mountains in the area where the boundaries of the four States converge are five national forests — the Cherokee, Pisgah, Nantahala, Chattahoochee, and Sumter. The more eastern of the ranges on the slopes of which thesefo rests lie is the Blue Ridge which rises abruptly out of the Piedmont country and forms the divide between waters flowing southeast and south into the Atlantic Ocean and northwest to the Tennessee River en route to the Gulf of Mexico. The southeastern slope of the ridge is cut deeply by the rivers which rush toward the plains, the top is rounded, and the northwestern slopes are gentle. Only a few of its peaks rise as much as a mile above the sea. The western range, roughly paralleling the Blue Ridge and connected to it by transverse ranges, is divided into segments by rivers born high on the slopes between the transverse ranges. -

Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Great Smoky Mountains National Park

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Service National Park Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Resource Historic Park National Mountains Smoky Great Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 April 2016 VOL Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 1 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historic places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. GRSM 133/134404/A April 2016 GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 FRONT MATTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... -

Huckleberry Knob Hike

Huckleberry Knob – Nantahala National Forest, NC Length Difficulty Streams Views Solitude Camping 1.8 mls N/A Hiking Time: 1 hour and 10 minutes with 30 minutes of breaks Elev. Gain: 370 ft Parking: There is space for only a few cars at the Huckleberry Knob Trailhead. 35.31391, -83.99098 If this lot is full, overflow parking is available on the grassy shoulder of the Cherohala Skyway west of the entrance. By Trail Contributor: Zach Robbins Huckleberry Knob, at 5,580 feet, is the highest peak in the remote Unicoi Mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee. The bald summit is reached by an easy hike from the Cherohala Skyway. Suitable for all levels of hiking experience, the grassy bald provides fantastic 360° views of the Unicoi, Great Smoky, Cheoah, Snowbird, Nantahala, Valley River, Tusquitee, and Cohutta Mountain ranges of southwestern North Carolina, northeastern Georgia, and southeastern Tennessee. This is one of the finest viewpoints in the region, only rivaled by Gregory Bald, Rocky Top, and lookout towers on Shuckstack and Wesser Bald. This is a wonderful spot for a picnic or lazy backcountry camping. While in the area, consider including other nearby trails along the Cherohala Skyway for a full day of short hikes. Mile 0.0 – There is space for only a few cars at the Huckleberry Knob Trailhead. If this lot is full, overflow parking is available on the grassy shoulder of the Cherohala Skyway west of the entrance. The Huckleberry Knob Trail [419] follows a forest road track through beech and maple forests. Mile 0.4 – Follow the shoulder of Oak Knob through wide open grassy fields.