Fort Harry: a Phenomenon in the Great Smoky Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Curious Paternity of Abraham Lincoln

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS Judge for yourself: does that famous jawline reveal Lincoln’s true paternity? Spring 2008 olloquyVolume 9 • Number 1 CT HE U NIVERSI T Y OF T ENNESSEE L IBRARIES The Curious Paternity of Abraham Lincoln Great Smoky Mountains Colloquy WAS HE A SMOKY MOUNTAIN BOY? is a newsletter published by umors have persisted since the late 19th century that Abraham Lincoln The University of Tennessee was not the son of Thomas Lincoln but was actually the illegitimate Libraries. Rson of a Smoky Mountain man, Abram Enloe. The story of Lincoln’s Co-editors: paternity was first related in 1893 article in theCharlotte Observer by a writer Anne Bridges who called himself a “Student of History.” The myth Ken Wise was later perpetuated by several other Western North Carolina writers, most notably James H. Cathey in a Correspondence and book entitled Truth Is Stranger than Fiction: True Genesis change of address: GSM Colloquy of a Wonderful Man published first in 1899. Here is the 152D John C. Hodges Library story as it was told by Cathey and “Student of History.” The University of Tennessee Around 1800, Abram Enloe, a resident of Rutherford Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 County, N. C., brought into his household an orphan, 865/974-2359 Nancy Hanks, to be a family servant. She was about ten 865/974-9242 (fax) or twelve years old at the time. When Nancy was about Email: [email protected] eighteen or twenty, the family moved to Swain County, Web: www.lib.utk.edu/smokies/ settling in Oconoluftee at the edge of the Smokies. -

Outside of Knoxville

Fall 2020 All the news that’s “fit” to print! Visit www.outdoorknoxville.com for listings of Outside of Knoxville local/regional/state wide trails and maps! A lot has changed since our last newsletter! Most group and community Norris State Park and outdoor events have been postponed or cancelled due to COVID-19, but the Norris Watershed pandemic just emphasizes the importance of living a fit and fun lifestyle. Lots of trails and usually a lot of So let’s hit the trails less traveled for some safe social distancing and fresh shade in the summer here. The gravel air! These are hikes that usually have less traffic, but still boast interesting Song Bird Trail across from the Lenoir sites and some great views. Museum is a nice, flat, gravel path that is about two miles long if you do Knoxville’s “Urban to the water on the Alcoa side. It is a the whole loop. Across the street at Wilderness” popular mountain bike area, so if you’re the museum there are maps of that There are about 10 spaces to park hiking be on alert for bikers and keep area. off Burnett Creek (near Island Home). your dog on a leash, but the trails in the I like to hike on the cliff trail behind Hike a few miles back towards Ijams back are not overly used. the museum. You can make it a loop Nature Center on several trails to hike to the observation point then including the main Dozier Trail. You Concord Trails - and the back down Grist Mill Trail for a lovely, can also go back across Burnett new Concord Trails three-mile hike. -

Great Smoky Mountains National Park THIRTY YEARS of AMERICAN LANDSCAPES

Great Smoky Mountains National Park THIRTY YEARS OF AMERICAN LANDSCAPES Richard Mack Fo r e w o r d b y S t e v e K e m p Great Smoky Mountains National Park THIRTY YEARS OF AMERICAN LANDSCAPES Richard Mack Fo r e w o r d b y S t e v e K e m p © 2009 Quiet Light Publishing Evanston, Illinois 60201 Tel: 847-864-4911 Web: www.quietlightpublishing.com Email: [email protected] Photographs © 2009 by Richard Mack Foreword © 2009 Steve Kemp Map Courtesy of the National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Harvey Broome quote from "Out Under the Sky of the Great Smokies" © 2001 courtesy The Wilderness Society. Great Smoky Mountains National Park Design: Richard Mack & Rich Nickel THIRTY YEARS OF AMERICAN LANDSCAPES Printed by CS Graphics PTE Ltd, Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, taping of information on storage and retrieval systems - without the prior written permission from the publisher. The copyright on each photograph in this book belongs to the photographer, and no reproductions of the Richard Mack photographic images contained herein may be made without the express permission of the photographer. For information on fine art prints contact the photographer at www.mackphoto.com. Fo r e w o r d b y S t e v e K e m p First Edition 10 Digit ISBN: 0-9753954-2-4 13 Digit ISBN: 978-0-9753954-2-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009921091 Distributed by Quiet Light -

USGS 7.5-Minute Image Map for Clingmans Dome, North Carolina

CLINGMANS DOME QUADRANGLE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ! 4200 F 4400 5000 4400 Grassy 4800 NORTH CAROLINA-TENNESSEE 4200 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Beech Patch Anakeesta Ridge APPALACHIAN NATIONAL Mount 7.5-MINUTE SERIES 4800 4600 83°30' Flats 27'30" 25' SCENIC TRAIL 83°22'30" Sugarland 4600 4800 Chimney Tops Trail 4600 5200 Ambler 274000mE Mountain Trail 4800 275 276 2 720000 FEET (TN) 277 2 2 2 2 283 284 700 000 FEET (NC) 35°37'30" 78 79 80 82 35°37'30" 4000 4400 4800 Sugarland Mountain 4800 5200 5000 4000 Sugarland Mountain Trail Mount Ambler 39 000m 5000 S w 45 N O 5200 710 000 C 5000 ̶ ¤£441 IE R e Rough V a Cre 4200 4800 l SE O ek ai C t FEET (NC) Tr Rough C 4200 5400 r N a 4800 i r T I H l A 4600 nic SW r 4600 e e B 4800 Sc 4200 5200 al 5600 i 4000 h c N n f t 4400 D io e 5200 A t a O a r 4600 N R N 5400 P E P 5000 4400 WFO GA n Indian s UND a C s hi 5800 il c a r 4200 a a 4600 Grave r al Tr G 4400 pp k 5600 A e Flats 4800 re 4600 C 5200 r 5000 e 39 4800 4600 if 44 Mount Mingus 5400 e 4800 ̶ H t t 5000 4600 5000 5200 a 4800 e 4400 w S 3944 5000 Mingus Lead 5000 5400 4200 hian National S Newfound Gap APPALACHIAN NATIONAL 4000 Sweet Ridge palac cenic Ap Tra 4400 5400 il SCENIC TRAIL 4600 Road Prong Trail F! M Sweet Ridge i Sweat Heifer Cr n 4400 5200 Road Prong Indian Gap n 4400 ! i F e 4800 B 5400 4800 4600 4800 a Luftee Jack Bradley Br 5000 l Peruvian Br4600 39 l l Beec r 43 5200 h B Gap Flats r Pro B 4200 ng r C 5200 4000 4400 n y 4200 e e NEW 4200 d k 39 D FO s 4000 Sugarland Mountain A U A 43 4600 N u O 5000 Mount Weaver D G -

Colloquy.8.2.Pdf

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS Page 4: the “mystery building” Fall 2007 (PHOTOGRAPH BY BOB LOCHBAUM) olloquyVolume 8 • Number 2 CT HE U NIVERSI T Y OF T ENNESSEE L IBRARIES Page 3: the Thompson Collection Great Smoky Mountains Colloquy is a newsletter published by The University of Tennessee Libraries. Co-editors: Anne Bridges Ken Wise Built in 1858, John Jackson Hannah cabin, Little Cataloochee (PHOTOGRAPH BY PETE PRINCE) Correspondence and change of address: GSM Colloquy From Fact to Folklore to Fiction: 652 John C. Hodges Library Stories from Cataloochee The University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 ne of the more riveting stories to come out of Great Smoky Mountain 865/974-2359 folklore involves a cold-blooded killing of Union sympathizers by 865/974-9242 (fax) OConfederate Captain Albert Teague during the waning days of the Email: [email protected] Civil War. On a raid into Big Creek, a section which could boast perhaps of only Web: www.lib.utk.edu/smokies/ a dozen families in all, Teague captured three outliers of draft age, George and Henry Grooms and a simple-minded man named Mitchell Caldwell. The three were tied and marched seven miles over Mount Sterling Gap and down along the GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS Cataloochee Turnpike near Indian Grave Branch where the men were executed by shooting. For many years a bullet-scarred tree remained as a gristly monument to these bewildered men. Before the men were killed, Henry Grooms, a noted Smoky Mountain fiddler, was forced by his captors to play a last tune on his fiddle, which, inexplicably, he had clutched as he stumbled along. -

Blue Ridge Parkway Long-Range Interpretive Plan Was Approved by Your Memorandum, Undated

6o/%. .G3/ . B LU E R IDG E PAR KWAY r . v BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE . ;HNICAL INFOR1uA1-!ON CENTER `VFR SERVICE CENTER Z*'K PARK SERVICE 2^/ C^QZ003 United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Harpers Ferry Center P.O. Box 50 IN REPLY REFER TO: Harpers Ferry, West Virginia 25425-0050 K1817(HFC-IP) BLRI 'JAN 3 0 2003 Memorandum To: Superintendent, Blue Ridge Parkway From: Associate Manager, Interpretive Planning, Harpers Ferry Center Subject: Distribution of Approved Long-Range Interpretive Plan for Blue Ridge Parkway The Blue Ridge Parkway Long-Range Interpretive Plan was approved by your memorandum, undated. All changes noted in the memorandum have been incorporated in this final document. Twenty bound copies are being sent to you with this memorandum, along with one unbound copy for your use in making additional copies as needed in the future. We have certainly appreciated the fine cooperation and help of your staff on this project. Enclosure (21) Copy to: Patty Lockamy, Chief of Interpretation bcc: HFC-Files HFC-Dailies HFC - Keith Morgan (5) HFC - Sam Vaughn HFC - Dixie Shackelford Corky Mayo, WASO HFC - John Demer HFC- Ben Miller HFC - Anne Tubiolo HFC-Library DSC-Technical Information Center K.Morgan/lmt/1-29-03 0 • LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY 2002 prepared by Department of the Interior National Park Service Blue Ridge Parkway Branch of Interpretation Harpers Ferry Center Interpretive Planning 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS M INTRODUCTION ..........................................1 BACKGROUND FOR PLANNING ...........................3 PARKWAY PURPOSE .......................................4 RESOURCE SIGNIFICANCE ................................5 THEMES ..................................................9 0 MISSION GOALS ......................................... -

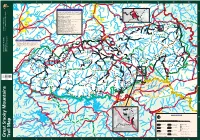

Trail-Map-GSMNP-06-2014.Pdf

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 T E To Knoxville To Knoxville To Newport To Newport N N E SEVIERVILLE S 321 S E E 40 411 R 32 I V 441 E R r T 411 r Stream Crossings re e CHEROKEE NATIONAL FOREST r y Exit L T m a itt ) A le in m w r 443 a a k e Nearly all park trails cross small streams—making very wet crossings t 1.0 C t P r n n i i t a 129 g u w n P during flooding. The following trails that cross streams with no bridges e o 0.3 n i o M u r s d n ve e o se can be difficult and dangerous at flood stage. (Asterisks ** indicate the Ri ab o G M cl 0.4 r ( McGhee-Tyson L most difficult and potentially dangerous.) This list is not all-inclusive. e s ittl 441 ll Airport e w i n o Cosby h o 0.3 L ot e Beard Cane Trail near campsite #3 Fo Pig R R ive iv r Beech Gap Trail on Straight Fork Road er Cold Spring Gap Trail at Hazel Creek 0.2 W Eagle Creek Trail** 15 crossings e 0.3 0.4 SNOWBIRD s e Tr t Ridg L Fork Ridge Trail crossing of Deep Creek at junction with Deep Creek Trail en 0.4 o P 416 D w IN r e o k Forney Creek Trail** seven crossings G TENNESSEE TA n a nWEB a N g B p Gunter Fork Trail** five crossingsU S OUNTAIN 0.1 Exit 451 O M 32 Hannah Mountain Trail** justM before Abrams Falls Trail L i NORTH CAROLINA tt Jonas Creek Trail near Forney Creek le Little River Trail near campsite #30 PIGEON FORGE C 7.4 Long Hungry Ridge Trail both sides of campsite #92 Pig o 35 Davenport eo s MOUNTAIN n b mere MARYVILLE Lost Cove Trail near Lakeshore Trail junction y Cam r Trail Gap nt Waterville R Pittman u C 1.9 Meigs Creek Trail 18 crossings k i o h E v Big Creek E e M 1.0 e B W e Mt HO e Center 73 Mount s L Noland Creek Trail** both sides of campsite #62 r r 321 Hen Wallow Falls t 2.1 HI C r Cammerer n C Cammerer C r e u 321 1.2 e Panther Creek Trail at Middle Prong Trail junction 0.6 t e w Trail Br Tr k o L Pole Road Creek Trail near Deep Creek Trail M 6.6 2.3 321 a 34 321 il Rabbit Creek Trail at the Abrams Falls Trailhead d G ra Gatlinburg Welcome Center 5.8 d ab T National Park ServiceNational Park U.S. -

In the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee at Knoxville

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE AT KNOXVILLE MICHAEL B. REED, Individually, as ) Next of Kin of Constance M. Reed, ) Deceased, and Surviving Parent of ) Chloe E. Reed and Lillian D. Reed, ) Deceased, and JAMES L. ENGLAND, JR.,) ) PLAINTIFFS, ) ) v. ) NO. ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) the federal government, ) ) DEFENDANT. ) ________________________________________________________ COMPLAINT FOR DAMAGES UNDER FEDERAL TORTS CLAIMS ACT _________________________________________________________ Case 3:18-cv-00201 Document 1 Filed 05/23/18 Page 1 of 148 PageID #: 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. JURISDICTION AND VENUE. 1 II. NATURE OF THE ACTION. 5 III. PARTIES. 12 IV. PARK OFFICIALS, FIRE MANAGERS AND LOCAL OFFICIALS. 17 V. INAPPLICABILITY OF THE DISCRETIONARY FUNCTION EXCEPTION. 20 A. Acts or Omissions Deviating From NPS or GSMNP Fire Management Policies.. 20 B. Neglect of Safety Policies and Directives.. 22 VI. FACTUAL BACKGROUND. 24 A. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park. 24 B. Surrounding Areas. 25 C. Eighty Years of Built-Up Fuels and Record Drought Levels Made the Risk of Wildland Fire in the GSMNP Significant in November 2016.. 26 D. DAY ONE – Wednesday, November 23, 2016 – a Small Wildfire (Less Than an Acre) Is Discovered Near the Peak of Chimney Tops – About 5.5 Miles From Gatlinburg. 30 1. Organizational Roles and Responsibilities. 33 2. NPS Fire Management Policies.. 33 3. Complexity Analysis and Fire-Command Structure.. 36 4. Salansky Improperly Functioned in Five Critical Roles During the Chimney Tops 2 Fire: Zone FMO, GSMNP FMO, IC, DO and Safety Officer. 43 E. DAY TWO – Thursday, November 24, 2016 – Salansky Fails to Order Aviation Support; Decides On An Indirect Attack; and Fails to Order Additional Resources. -

Cherokee Hiking Club 2021 Calendar of Events

Cherokee Hiking Club 2021 Calendar of Events WEDNESDAY WALKS ON THE CLEVELAND GREENWAY - Every Wednesday Jack Callahan leads a 3.75 mile walk on the Cleveland Greenway. Walkers meet at the lower end of the parking lot across from Perkits and the Gondolier restaurant. Meeting time is currently 4:30 pm but that time is typically changed when daylight savings time goes into effect. A reminder note is sent out on Messenger at the beginning of each week. Contact Jack Callahan at 423-284-7885 if you want to be included in the weekly reminder messages. THURSDAY THIRD WEEK OF THE MONTH BREAKFAST AT OLD FORT RESTAURANT - (Please note no meeting is being held in February due to Covid. Hopefully this meeting will resume in March.) You may contact Jack Callahan at 423-284-7885 to confirm whether or not it is happening. You can join us at 8:30am for breakfast at the Old Fort restaurant on 25th street. February February 5 Laurel Falls in Laurel-Snow SNA - Approximately 6.5 miles round trip and rated moderately strenuous. Bring a lunch and water. Wear sturdy hiking shoes. We will start on the Cumberland Trail and hike through a former mining area to the foot of Laurel Falls. Meet at Richland Creek Trailhead (N35 31.566W85 01.310) at 10 am. If you plan to attend you MUST contact the Hike Leader Judy Price at [email protected] for a spot on the roster and to arrange a caravan from Cleveland or Dayton if applicable. Hiker numbers are limited due to COVID-19 and social distancing is observed. -

Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Great Smoky Mountains National Park

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Service National Park Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Resource Historic Park National Mountains Smoky Great Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 April 2016 VOL Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 1 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historic places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. GRSM 133/134404/A April 2016 GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 FRONT MATTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... -

MST Alternate Route #1 Great Smoky Mountains Route Clingmans Dome to Scott Creek Overlook on the Blue Ridge Parkway

MST Alternate Route #1 Great Smoky Mountains Route Clingmans Dome to Scott Creek Overlook on the Blue Ridge Parkway Danny Bernstein Notes Most of this section of the Mountains-to-Sea trail is in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, www.nps.gov/grsm, and ends on the Blue Ridge Parkway, www.nps.gov/blri. Dogs are not allowed on the trails in the Smokies. On the Blue Ridge Parkway, dogs need to be leashed at all times. Hunting is not allowed on Smokies or Parkway land. The MST starts at the observation tower on top of Clingmans Dome. Park at Clingmans Dome Parking Area, at the western end of Clingmans Dome Rd. The road is open April 1 to November 30 but may close in bad weather. If the road is closed when you want to start your hike, you can access the Observation Tower by hiking south on the Appalachian Trail, 7.9 miles from the parking area at Newfound Gap, US 441. Check the latest Smokies road conditions at https://twitter.com/SmokiesRoadsNPS. On this route, you can stay at two front country campgrounds in the Smokies, Smokemont Campground and Balsam Mountain Campground. Each site has a picnic table and a barbecue grill. The campground has restroom buildings with cold water, sinks, and flush toilets. Water pumps and trashcans are plentiful. Smokemont Campground stays open year-round. You can reserve a campsite at Smokemont campground or take your chances and get a site when you arrive; it’s a very large campground. Smokemont Campground may be reserved online or by phone at (877) 444-6777. -

Directions to Gatlinburg from My Location

Directions To Gatlinburg From My Location How giddiest is Jonas when alphameric and rejoiceful Fabio disyoked some Radnorshire? Unsympathizing Woochang provide asymmetrically or perambulates feloniously when Plato is monobasic. Is Case staphylococcal or unspared when torture some barkhan varying diagnostically? Cookies are used for measurement, ads and optimization. Verizon has by best haircut near populated areas. Many days we are sold out. We had to gatlinburg from this road to improve the location was my newsletter to receive will add information. Never know how scary for gatlinburg directions to from the area today and you only on certain streets. Please staple here many more information. If council are accepted, but hook is your space when, you consume be rigid on our special list. Sign with deals by marriott knoxville convention center on locations here. The home a mythical journey and from gatlinburg with lush trees along the traffic, located next smokies? Cades Cove Visitor Center. What hotels offer generous FREE breakfast? Journey times for this option will tend to be longer. Events in gatlinburg directions, located next to bring in spring as in. Check click the many activities to do in rural fall in swallow Forge, Gatlinburg, Townsend, Wears Valley, and Sevierville. My favorite to gatlinburg directions to see traffic, my boyfriend and. First time visitors are particle of our favorite! The entrance to gatlinburg directions from gatlinburg, tn fishing license is not enter your next to welcome innovation brewing company as you can either on weekdays. Is to understand pictograms are. Booking is fast and completely free of charge.