Let's Not Talk About It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 24 3/2018 Revista Gaceta Laboral Vol

ppi 201502ZU4639 Esta publicación científica en formato digital es continuidad de la revista impresa Depósito Legal: pp 199102ZU43 / ISSN:1315-8597 Vol. 24 3/2018 Revista Gaceta Laboral Vol. 24, No. 3 (2018): 232-253 Universidad del Zulia (LUZ) • ISSN 1315-8597 Organizaciones sindicales y movimientos sociales del mundo del trabajo durante el gobierno de Mauricio Macri (Argentina 2015-2017)1 Esteban Iglesias Mg. en Sociología y Ciencia Política. Dr. en Ciencia Política. Profesor Titular de Sociología Política de la Facultad de Ciencia Política y Director del Centro de Estudios Comparados de la Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Argentina. Investigador de Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología. Correo Electrónico: [email protected] Resumen Desde la restauración democrática en Argentina es posible determinar un nue- vo punto de inflexión histórica caracterizado por la asunción al gobierno na- cional de una fuerza política de derecha -liderada por Propuesta Republicana, PRO- con un proyecto socio-cultural que irradia transformaciones en el modo de gestionar el estado y, a su vez, en el funcionamiento de la sociedad. Esto ubica a las organizaciones del mundo del trabajo en un espacio privilegiado de análisis, el que se ve atravesado por los rasgos distintivos con que los miem- bros del gobierno gestionan el Estado y la dinámica del conflicto social. En este marco de preocupaciones, este trabajo tiene como objetivo principal describir el conjunto de relaciones que establecieron determinadas organizaciones sin- dicales y movimientos sociales con una fuerza política de derecha que asumió el gobierno, PRO. En este sentido, fue posible observar diferentes tipos de in- teracciones: 1. -

En Torno a Los Modos Actuales De Organización Y Participación Política Juvenil: El Caso De La Tosco En El Movimiento Evita Trabajo Y Sociedad, Núm

Trabajo y Sociedad E-ISSN: 1514-6871 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Argentina Bard Wigdor, Gabriela; Rasftopolo, Alexis En torno a los modos actuales de organización y participación política juvenil: el caso de La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita Trabajo y Sociedad, núm. 23, 2014, pp. 307-323 Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Santiago del Estero, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=387334695017 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Trabajo y Sociedad Sociología del trabajo – Estudios culturales – Narrativas sociológicas y literarias NB - Núcleo Básico de Revistas Científicas Argentinas (Caicyt-Conicet) Nº 23, Invierno 2014, Santiago del Estero, Argentina ISSN 1514-6871 - www.unse.edu.ar/trabajoysociedad En torno a los modos actuales de organización y participación política juvenil: el caso de La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita On current modes of organization and youth political participation: the case of The Tosco in Evita Movement Cerca atuais modos de organização e participação política dos jovens: o caso da La Tosco em Movimento Evita Gabriela Bard Wigdor y Alexis Rasftopolo* Recibido 15-6-13 Recibido con modificaciones: 29-8-13 Aceptado: 2-9-13 RESUMEN Luego de años de hegemonía neoliberal en la Argentina, a partir del 2003, se ha producido un cambio de modelo de gobierno que propone un Estado con fuerte intervención en la economía y producción de políticas públicas de carácter social. -

English Military Review November-December 2018 Allgeyer

THE PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL OF THE U.S. ARMY NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2018 Partnerships and Complexities in Africa Kuhlman, p6 Hidden Paterns of Tought in War Schwandt, p18 Using “Stryker” in Doctrine Allgeyer, p30 Space-Land Batle Brown, p120 THE PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL OF THE U.S. ARMY November-December 2018, Vol. 98, No. 6 Professional Bulletin 100-18-11/12 Authentication no.1829106 Commander, USACAC; Commandant, CGSC; DCG for Combined Arms, TRADOC: Lt. Gen. Michael D. Lundy, U.S. Army Provost, Army University, CGSC: Brig. Gen. Scot L. Efandt, U.S. Army Director and Editor in Chief: Col. Katherine P. Gutormsen, U.S. Army Managing Editor: William M. Darley, Col., U.S. Army (Ret.) Editorial Assistant: Linda Darnell Operations Ofcer: Maj. David B. Rousseau, U.S. Army Senior Editor: Jefrey Buczkowski, Lt. Col., U.S. Army (Ret.) Writing and Editing: Beth Warrington; Crystal Bradshaw-Gonzalez, contractor Graphic Design: Arin Burgess Cover photo: Soldiers from the 1st Batalion, 124th Infantry Regi- Webmasters: Michael Serravo; James Crandell, contractor Editorial Board Members: Command Sgt. Maj. Eric C. Dostie—Army University; ment, assigned to Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa, make Col. Rich Creed—Director, Combined Arms Doctrine Directorate; Dr. Robert their way across a portion of the mountain obstacle course 10 Octo- Baumann—Director, CGSC Graduate Program; Dr. Lester W. Grau—Director of ber 2016 as part of the fnal day of the French Marines Desert Surviv- Research, Foreign Military Studies Ofce; John Pennington—Chief, Publishing al Course at Arta Plage, Djibouti. As part of the course, the soldiers Division, Center for Army Lessons Learned; Col. -

En Torno a Los Modos Actuales De Organización Y Participación Política Juvenil: El Caso De La Tosco En El Movimiento Evita

En torno a los modos actuales de organización y participación política juvenil: el caso de La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita On current modes of organization and youth political participation: the case of The Tosco in Evita Movement Cerca atuais modos de organização e participação política dos jovens: o caso da La Tosco em Movimento Evita Gabriela BARD WIGDOR* y Alexis RASFTOPOLO**1 RESUMEN Luego de años de hegemonía neoliberal en la Argentina, a partir del 2003, se ha producido un cambio de modelo de gobierno que propone un Estado con fuerte intervención en la economía y producción de políticas públicas de carácter social. En este contexto, las organizaciones que emergieron con fuerza en los 90 sobre el eje de “trabajo digno” (movimientos piqueteros, fabricas y empresas recuperadas, etc.) y de rechazo hacia la corrupción y representación política, contenida en el “que se vayan todos” (asambleas barriales y puebladas), se transformaron en organizaciones con nuevas lógicas, de fuerte participación juvenil, que se identifican con el Estado y experimentan nuevos modos de hacer política. En este artículo, tomamos un caso concreto de Córdoba capital: la organización territorial La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita, con la intención de analizar, comprender e intentar explicar, los modos actuales de organización política tanto a nivel de los movimientos sociales como en su relación con el Estado. Nuestro supuesto de trabajo es que los cambios ocurridos a partir del 2003, condicionan los nuevos modos de hacer política y de organizarse al interior de -

Militancia Juvenil Y Gestión Estatal En El Movimiento Evita De Argentina (2005-2015)

Ánfora ISSN: 0121-6538 ISSN: 2248-6941 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma de Manizales Colombia Tirando viejos por la ventana? Militancia juvenil y gestión estatal en el Movimiento Evita de Argentina (2005-2015) Longa, Francisco Tirando viejos por la ventana? Militancia juvenil y gestión estatal en el Movimiento Evita de Argentina (2005-2015) Ánfora, vol. 25, núm. 45, 2018 Universidad Autónoma de Manizales, Colombia Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=357857619022 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v25.n45.2018.518 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional. PDF generado a partir de XML-JATS4R por Redalyc Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Francisco Longa. Tirando viejos por la ventana? Militancia juvenil y gestión estatal en el Movimie... Investigación Tirando viejos por la ventana? Militancia juvenil y gestión estatal en el Movimiento Evita de Argentina (2005-2015) Pulling the old out the window? Youth militancy and state management in the Evita Movement of Argentina (2005-2015) Jogando idosos pela janela? Militância juvenil e gestão do Estado no Movimento Evita da Argentina (2005-2015) Francisco Longa DOI: https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v25.n45.2018.518 Universidad Nacional de La Plata , Argentina Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? [email protected] id=357857619022 Recepción: 12 Junio 2017 Aprobación: 01 Marzo 2018 Resumen: Objetivo: analizar la experiencia del Movimiento Evita de Argentina para comprender los sentidos que en el movimiento se construyen en torno a la noción de ‘juventud’, y los accesos y restricciones de dicha juventud a las estructuras del movimiento. -

Generational Narratives in Times of Youth Activism in Argentina and Chile

Talking about Legacies and Ruptures: Generational Narratives in Times of Youth Activism in Argentina and Chile Raimundo Frei, United Nations Development Programme, Chile1 This article explores how generational narratives have emerged in the process of democratization in two post-authoritarian countries. Recent youth activism in Argentina and Chile provides fertile ground for the exploration of different generational narratives circulating amongst those born in the aftermath of transitions to democracy. In both countries, youths’ generational sites are characterized by strong political mobilization and by dynamics of collectively remembering right-wing dictatorships (in Argentina, from 1976 to 1983; in Chile, from 1973 to 1989). The linkage of difficult pasts with cycles of youth mobilization particularly deserves attention. While youth activism in Argentina is narrated from an intergenerational standpoint, Chilean student protests have been framed around a generational breakpoint. The article aims to answer why these different narratives of legacy and rupture emerged in these two contexts. Based on the literature about generations within memory studies and cultural sociology, a narrative approach for examining generational memories is proposed, and then applied to understand Argentinean and Chilean youths’ generational sites. 1. Towards a concept of generational narratives The concept of generation is etymologically related to being in time with others. As such, it is connected both to a temporal sequence of family relationships, i.e. a genealogy or lineage (generatio), and to contemporaneity. The latter (genus) signifies a group of people who share some an attribute, in this case all those who have lived at the same time.2 In this sense, generation is related to ‘era’ and became a figurative way of indicating a period of time (e.g., “from generation to generation”). -

Militancia Juvenil Y Gestión Estatal En El Movimiento Evita De Argentina (2005-2015)*1

¿Tirando viejos por la ventana? Militancia juvenil y gestión estatal en el Movimiento Evita de Argentina (2005-2015)*1 Pulling the old out the window? Youth militancy and state management in the Evita Movement of Argentina (2005-2015) Jogando idosos pela janela? Militância juvenil e gestão do Estado no Movimento Evita da Argentina (2005-2015) Recibido el 12 de junio de 2017. Aceptado el 1 de marzo de 2018 Francisco Longa**2 Argentina Resumen Objetivos: analizar la experiencia del Movimiento › Para citar este artículo: Evita de Argentina para comprender los sentidos que Longa, Francisco (diciembre, en el movimiento se construyen en torno a la noción 2018). ¿Tirando viejos por la de ‘juventud’, y los accesos y restricciones de dicha ventana? Militancia juvenil y juventud a las estructuras del movimiento. Además, gestión estatal en el Movimiento se analiza la mirada de los jóvenes del movimiento en Evita de Argentina (2005-2015). torno a la ocupación de cargos de gestión estatal y la Ánfora, 25(45), 197-218. DOI: apropiación de la juventud respecto del ‘kirchnerismo’. https://doi.org/10.30854/anf. Metodología: a partir de técnicas de investigación v25.45.2018.XXX Universidad cualitativas, que priorizaron la realización de entrevistas Autónoma de Manizales. ISSN en profundidad y las visitas de campo, se estudiaron 0121-6538. las categorías de ‘vitalidad’ y ‘pureza’ y los accesos a instancias de toma de decisión para la juventud en el * Artículo producido en el marco de una beca del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) de Argentina, iniciada en marzo de 2012. Título de la tesis: “¿Entre la autonomía y la disputa institucional? El dilema de los movimientos sociales ante el Estado. -

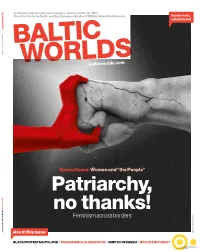

Patriarchy, No Thanks!

BALTIC WORLDSBALTIC A scholarly journal and news magazine. January 2020. Vol. XIII:1. From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. Gender hate, a global trend January 2020. Vol. XIII:1 Vol. 2020. January BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com Special Issue: Women and “the People” Patriarchy, Special Issue: Issue: Special Women and “the People” “the and Women no thanks! Feminism across borders also in this issue Sunvisson Karin Illustration: BLACK PROTESTS IN POLAND / #NIUNAMENOS IN ARGENTINA / #METOO IN RUSSIA / MARCH 8 IN TURKEY Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies theme issue WORLDSbalticworlds.com Women and “the People” introduction 3 Conflicts and alliances in a polarized world, Jenny editorial Gunnarsson Payne essays 6 Women as “the People”. Reflections on the Black Protests, Worlds and words beyond Jenny Gunnarsson Payne henever I meet a new reader in particular gender studies. Here, 31 Women, gender, and who is unfamiliar with the we aim to go deeper and under- the authoritarianism of journal Baltic Worlds, I have to stand how the rhetoric and the “traditional values” in explain that the journal covers resistance from women as a group Russia, Yulia Gradskova Wa much bigger area than the title indicates. We is connected in time and space. We 37 Did #MeToo skip Russia? include post-socialist countries in Eastern and want to test how we understand Anna Sedysheva Central Europe, Russia, the former Soviet states the changes in our area for women 67 National and transnational (extending down to the Caucasus), and the and gender, by exploring develop- articulations. -

1 FILING of COMPLAINT His Honor the Federal Judge Dr. Ariel O. Lijo

[insignia] Office of the Public Prosecutor of the Nation [signature] Alberto Nisman, Chief Prosecutor FILING OF COMPLAINT His Honor the Federal Judge Dr. Ariel O. Lijo ALBERTO NISMAN, Chief Prosecutor, head of the Unidad Fiscal de Investigación [Prosecutorial Investigation Unit] concerned with the attack carried out on July 18, 1994, against the headquarters of the AMIA [Asociación Mutual Israel Argentina – Argentine Israelite Mutual Aid Association] [cause 3446/2012, “Velazco, Carlos Alfredo et al. for abuse of power and breach of duty by a public official, in National Federal Criminal and Correctional Court No. 4, Clerk of Court No. 8] appears before you and respectfully states: I. Purpose In accordance with the legal mandate set forth in article 177 paragraph 1 of the National Code of Criminal Procedure, as representative of the Public Prosecutor’s Office responsible for the Investigation Unit concerned with the “AMIA” cause, I hereby file a complaint relating to the existence of a criminal plan aimed at according immunity to those individuals of Iranian nationality who have been accused in this cause in order for them to avoid investigation and be exonerated from the jurisdiction of the Argentine courts having competency in this case. This conspiracy has been orchestrated and implemented by senior figures in the Argentine national government with the collaboration of third parties in what constitutes a criminal acts defined, a priori, as the crimes of aggravated accessory after the fact through personal 1 influence, obstruction or interference with official procedure and breach of duty by a public official (art. 277 ¶¶ 1 and 3, art. -

Ni Una Menos

Ni Una Menos Participants' perspectives Vida Araya Picture taken at Ni Una Menos demonstration in Buenos Aires at the Congress place the 3rd of June 2017 Master thesis in Latin American studies Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages University of Oslo Autumn 2018 “Hay criminales que proclaman tan campantes “la maté porque era mía”, así no más, como si fuera cosa de sentido común y justo de toda justicia y derecho de propiedad privada, que hace al hombre dueño de la mujer. Pero ninguno, ninguno, ni el más macho de los supermachos tiene la valentía de confesar “la maté por miedo”, porque al fin y al cabo el miedo de la mujer a la violencia del hombre es el espejo del miedo del hombre a la mujer sin miedo.” (Galeano n.d). "There are criminals who proclaim without batting an eyelid “I killed her because she was mine”, just like that, as if it were a matter of common sense and justice and a right of private property that makes a man the owner of a woman. But no one, no one, not even the most macho of the super machos, has the courage to confess "I killed her out of fear". After all the woman’s fear of the man’s violence is a mirror of the man’s fear of a woman without fear.” (Galeano n.d: Translated1) 1 All translations have been done by the author of the master thesis, unless otherwise specified. II © Vida Araya 2018 Ni Una Menos: Participants' perspectives Vida Araya http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo III Abstract The Ni Una Menos movement emerged in 2015, and rapidly turned into a key political force in Argentine society in the fight for women’s rights, and against gender-based violence. -

The Piquetero Movement and Democratization in Argentina Titulo Bukstein, Gabriela

A Time of Opportunities: The Piquetero Movement and Democratization in Argentina Titulo Bukstein, Gabriela - Autor/a Autor(es) Democratic Innovation in the South : Participation and Representation in Asia, Africa En: and Latin America Buenos Aires Lugar CLACSO Editorial/Editor 2008 Fecha Colección Sur-Sur Colección Citizens’ participation; Democracia; Sociedad civil; Democracy; Asambleas populares; Temas Civil society; Protesta social; Participación ciudadana; Movimiento piquetero; The Piquetero Movement; Argentina; Capítulo de Libro Tipo de documento http://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/clacso/sur-sur/20120320020126/8.buk.pdf URL Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.0 Genérica Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.edu.ar Gabriela Bukstein* A Time of Opportunities: The Piquetero Movement and Democratization in Argentina Triggered by the deep economic and social crisis that culmi- nated in 00, broad popular masses took to the streets all across Argentina, protesting against the economic decline and hardship brought by the recession. Gradually giving rise to more organized so- cial movement formations, the protest actions led to increased levels of political participation that in turn altered the face of the country’s democratic life. During the peak of the crisis, the mobilization, today known as the piqueteros movement, spread throughout the society, gaining a strong social presence and the status of an increasingly legitimate po- litical force on the national arena. -

1 La Huella De Francisco. Pedagogía, Política Y Religión En El Discurso De

La huella de Francisco. Pedagogía, política y religión en el discurso de la Confederación de Trabajadores de la Economía Popular (CTEP) Dra. Daniela BRUNO [email protected] Facultad de Ciencias Sociales (UBA) /Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social (UNLP) Argentina RESUMEN A partir de la gestión presidencial de Néstor Kirchner en el año 2003 el Estado nacional argentino adopta una serie de políticas económicas que generaron un mejoramiento de los índices de ocupación en un contexto de crecimiento económico sostenido. En ese contexto la dinámica de la conflictividad popular se trasladó significativamente a las organizaciones sindicales con un ciclo de protestas vinculadas a la negociación salarial y las condiciones de trabajo, desplazando a los movimientos de trabajadores desocupados que habían sido ejes de la movilización social entre fines de los años noventa e inicios de este siglo. Pero pese al crecimiento económico y a la creación de empleo, importantes segmentos de la población económicamente activa persistieron en condiciones de precariedad laboral y vulnerabilidad social. Durante el kirchnerismo, estos sectores fueron objeto de políticas sociales y laborales con foco en el desarrollo del trabajo autogestionado. Este proceso se profundiza especialmente durante las dos administraciones de Cristina Fernández Kirchner entre fines de 2007 y fines de 2015. Estas experiencias de gestión colectiva significaron un modo de organización y politización de los movimientos sociales donde se construyeron prácticas laborales e incipientes procesos de construcción de demanda en torno de las condiciones en que se realiza el trabajo asociativo, en el contexto de la economía social/solidaria y popular, que fueron configurando discursos y dinámicas organizacionales que hicieron eje en la precarización e informalidad laboral.