Political Training in Four Generations of Activists in Argentina and Brazil*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

55 130516 Informe Especial El Congreso Argentino.Indd

SPECIAL REPORT The Argentinian Congress: political outlook in an election year Buenos Aires, May 2013 BARCELONA BOGOTÁ BUENOS AIRES LIMA LISBOA MADRID MÉXICO PANAMÁ QUITO RIO J SÃO PAULO SANTIAGO STO DOMINGO THE ARGENTINIAN CONGRESS: POLITICAL OUTLOOK IN AN ELECTION YEAR 1. INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION 2. WHAT HAPPENED IN 2012? 3. 2013 OUTLOOK On 1st March 2013, the president of Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, opened a new regular sessions’ period in the Argentinian 4. JUSTICE REFORM AND ITS Congress. POLITICAL CONSEQUENCES 5. 2013 LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS In her message, broadcasted on national radio and television, the 6. CONCLUSIONS head of state summarized the main economic indicators of Argentina AUTHORS and how they had developed over the last 10 years of Kirchner’s LLORENTE & CUENCA administration, a timeframe she called “a won decade”. National deputies and senators, in Legislative Assembly, attended the Presidential speech after having taken part in 23 sessions in each House, which strongly contrasts with the fi gure registered in 2011, when approximately a dozen sessions were held. The central point of her speech was the announcement of the outlines of what she called “the democratization of justice”. The modifi cation of the Judicial Council, the creation of three new Courts of Cassation and the regulation of the use of precautionary measures in lawsuits against the state were, among others, the initiatives that the president promised to send to Congress for discussion. Therefore, the judicial system reform became the main political issue in the 2013 public agenda and had a noteworthy impact on all areas of Argentinian society. -

The Politics of Patronage Appointments in Argentina's And

www.ssoar.info Unpacking Patronage: the Politics of Patronage Appointments in Argentina's and Uruguay's Central Public Administrations Larraburu, Conrado Ricardo Ramos; Panizza, Francisco; Scherlis, Gerardo Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Larraburu, C. R. R., Panizza, F., & Scherlis, G. (2018). Unpacking Patronage: the Politics of Patronage Appointments in Argentina's and Uruguay's Central Public Administrations. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 10(3), 59-98. https:// nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-11421 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-ND Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-ND Licence Keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NoDerivatives). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/deed.de Journal of Politics in Latin America Panizza, Francisco, Conrado Ricardo Ramos Larraburu, and Gerardo Scherlis (2018), Unpacking Patronage: The Politics of Patronage Appointments in Argentina’s and Uruguay’s Central Public Administrations, in: Journal of Politics in Latin America, 10, 3, 59–98. URN: http://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-4-11421 ISSN: 1868-4890 (online), ISSN: 1866-802X (print) The online version of this article can be found at: <www.jpla.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of Latin American Studies and Hamburg University Press. The Journal of Politics in Latin America is an Open Access publication. -

Vol. 24 3/2018 Revista Gaceta Laboral Vol

ppi 201502ZU4639 Esta publicación científica en formato digital es continuidad de la revista impresa Depósito Legal: pp 199102ZU43 / ISSN:1315-8597 Vol. 24 3/2018 Revista Gaceta Laboral Vol. 24, No. 3 (2018): 232-253 Universidad del Zulia (LUZ) • ISSN 1315-8597 Organizaciones sindicales y movimientos sociales del mundo del trabajo durante el gobierno de Mauricio Macri (Argentina 2015-2017)1 Esteban Iglesias Mg. en Sociología y Ciencia Política. Dr. en Ciencia Política. Profesor Titular de Sociología Política de la Facultad de Ciencia Política y Director del Centro de Estudios Comparados de la Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Argentina. Investigador de Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología. Correo Electrónico: [email protected] Resumen Desde la restauración democrática en Argentina es posible determinar un nue- vo punto de inflexión histórica caracterizado por la asunción al gobierno na- cional de una fuerza política de derecha -liderada por Propuesta Republicana, PRO- con un proyecto socio-cultural que irradia transformaciones en el modo de gestionar el estado y, a su vez, en el funcionamiento de la sociedad. Esto ubica a las organizaciones del mundo del trabajo en un espacio privilegiado de análisis, el que se ve atravesado por los rasgos distintivos con que los miem- bros del gobierno gestionan el Estado y la dinámica del conflicto social. En este marco de preocupaciones, este trabajo tiene como objetivo principal describir el conjunto de relaciones que establecieron determinadas organizaciones sin- dicales y movimientos sociales con una fuerza política de derecha que asumió el gobierno, PRO. En este sentido, fue posible observar diferentes tipos de in- teracciones: 1. -

En Torno a Los Modos Actuales De Organización Y Participación Política Juvenil: El Caso De La Tosco En El Movimiento Evita Trabajo Y Sociedad, Núm

Trabajo y Sociedad E-ISSN: 1514-6871 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Argentina Bard Wigdor, Gabriela; Rasftopolo, Alexis En torno a los modos actuales de organización y participación política juvenil: el caso de La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita Trabajo y Sociedad, núm. 23, 2014, pp. 307-323 Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Santiago del Estero, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=387334695017 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Trabajo y Sociedad Sociología del trabajo – Estudios culturales – Narrativas sociológicas y literarias NB - Núcleo Básico de Revistas Científicas Argentinas (Caicyt-Conicet) Nº 23, Invierno 2014, Santiago del Estero, Argentina ISSN 1514-6871 - www.unse.edu.ar/trabajoysociedad En torno a los modos actuales de organización y participación política juvenil: el caso de La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita On current modes of organization and youth political participation: the case of The Tosco in Evita Movement Cerca atuais modos de organização e participação política dos jovens: o caso da La Tosco em Movimento Evita Gabriela Bard Wigdor y Alexis Rasftopolo* Recibido 15-6-13 Recibido con modificaciones: 29-8-13 Aceptado: 2-9-13 RESUMEN Luego de años de hegemonía neoliberal en la Argentina, a partir del 2003, se ha producido un cambio de modelo de gobierno que propone un Estado con fuerte intervención en la economía y producción de políticas públicas de carácter social. -

English Military Review November-December 2018 Allgeyer

THE PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL OF THE U.S. ARMY NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2018 Partnerships and Complexities in Africa Kuhlman, p6 Hidden Paterns of Tought in War Schwandt, p18 Using “Stryker” in Doctrine Allgeyer, p30 Space-Land Batle Brown, p120 THE PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL OF THE U.S. ARMY November-December 2018, Vol. 98, No. 6 Professional Bulletin 100-18-11/12 Authentication no.1829106 Commander, USACAC; Commandant, CGSC; DCG for Combined Arms, TRADOC: Lt. Gen. Michael D. Lundy, U.S. Army Provost, Army University, CGSC: Brig. Gen. Scot L. Efandt, U.S. Army Director and Editor in Chief: Col. Katherine P. Gutormsen, U.S. Army Managing Editor: William M. Darley, Col., U.S. Army (Ret.) Editorial Assistant: Linda Darnell Operations Ofcer: Maj. David B. Rousseau, U.S. Army Senior Editor: Jefrey Buczkowski, Lt. Col., U.S. Army (Ret.) Writing and Editing: Beth Warrington; Crystal Bradshaw-Gonzalez, contractor Graphic Design: Arin Burgess Cover photo: Soldiers from the 1st Batalion, 124th Infantry Regi- Webmasters: Michael Serravo; James Crandell, contractor Editorial Board Members: Command Sgt. Maj. Eric C. Dostie—Army University; ment, assigned to Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa, make Col. Rich Creed—Director, Combined Arms Doctrine Directorate; Dr. Robert their way across a portion of the mountain obstacle course 10 Octo- Baumann—Director, CGSC Graduate Program; Dr. Lester W. Grau—Director of ber 2016 as part of the fnal day of the French Marines Desert Surviv- Research, Foreign Military Studies Ofce; John Pennington—Chief, Publishing al Course at Arta Plage, Djibouti. As part of the course, the soldiers Division, Center for Army Lessons Learned; Col. -

“Bringing Militancy to Management”: an Approach to the Relationship

“Bringing Militancy to Management”: An Approach to the Relationship between Activism 67 “Bringing Militancy to Management”: An Approach to the Relationship between Activism and Government Employment during the Cristina Fernández de Kirchner Administration in Argentina Melina Vázquez* Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET); Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani; Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Abstract This article explores the relationship between employment in public administration and militant commitment, which is understood as that which the actors themselves define as “militant management.” To this end, an analysis is presented of three groups created within three Argentine ministries that adopted “Kirchnerist” ideology: La graN maKro (The Great Makro), the Juventud de Obras Públicas, and the Corriente de Libertación Nacional. The article explores the conditions of possibility and principal characteristics of this activism as well as the guidelines for admission, continuing membership, and promotion – both within the groups and within government entities – and the way that this type of militancy is articulated with expert, professional and academic capital as well as the capital constituted by the militants themselves. Keywords: Activism, expert knowledge, militant careers, state. * Article received on November 22, 2013; final version approved on March 26, 2014. This article is part of a series of studies that the author is working on as a researcher at CONICET and is part of the project “Activism and the Political Commitment of Youth: A Socio-Historical Study of their Political and Activist Experiences (1969-2011)” sponsored by the National Agency for Scientific and Technological Promotion, Argentine Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation (2012-2015), of which the author is the director. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Protest or Politics? Varieties of Teacher Representation in Latin America Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4rc371rp Author Chambers-Ju, Christopher Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Protest or Politics? Varieties of Teacher Representation in Latin America By Christopher Chambers-Ju A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonah Levy, Co-Chair Professor Ruth Berins Collier, Co-Chair Professor David Collier Professor Laura Stoker Professor Kim Voss Summer 2017 Abstract Protest or Politics? Varieties of Teacher Representation in Latin America by Christopher Chambers-Ju Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonah Levy, Co-Chair Professor Ruth Berins Collier, Co-Chair Scholars of Latin American politics have made contrasting predictions about the prospects for contemporary group-based interest representation. Some argue that democratization creates an opportunity for societal groups to intensify their participation in politics. The expansion of political rights, alongside free and fair elections, creates space for all major groups to take part in politics, crucially those excluded under authoritarian rule. Other scholars, by contrast, maintain that neoliberal economic reforms fragment and demobilize major groups. Changes in the economic model, they suggest, have severe consequences for labor organizations, which now have a limited political repertoire. My research challenges both of these claims, showing how the consequences of democracy and neoliberalism, rather than being uniform, have been uneven. -

The Challenges of Women's Participation In

International IDEA, 2002, Women in Parliament, Stockholm (http://www.idea.int). This is an English translation of Elisa María Carrio, “Los retos de la participacíon de las mujeres en el Parlamento. Una nueva Mirada al caso argentine,” in International IDEA Mujeres en el Parlamento. Más allá de los números, Stockholm, Sweden, 2002. (This translation may vary slightly from the original text. If there are discrepancies in the meaning, the original Spanish version is the definitive text). CASE STUDY The Challenges of Women’s Participation in the Legislature: A New Look at Argentina ELISA MARÍA CARRIO In Argentina, mass-based political parties included a degree of the participation of women going back to their early days, from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, but it was only in the 1980s that we saw the massive emergence of women in party politics. This led to changes in attitude in the search for points of agreement and common objectives. Many women understood that the struggle against women’s oppression should not be subordinated to other struggles, as it was actually compatible with them, and should be waged simultaneously. It was an historic opportunity, as Argentina was emerging from a lengthy dictatorship in which women had the precedent of the mobilizations of the grandmothers and mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, in their white scarves. While women in Argentina have had the right to “vote and be elected” since 1947, women’s systematic exclusion from the real spheres of public power posed one of the most crucial challenges to, and criticisms of, Argentina’s democracy. -

Biocell 2019

XXXVII Reunión Científica Anual de la Sociedad de Biología de Cuyo, San Luis, Argentina. e 0 XXXVII Reunión Científica Anual de la Sociedad de Biología de Cuyo, San Luis, Argentina. Libro de Resúmenes XXXVII Reunión Científica Anual Sociedad de Biología de Cuyo 5 y 6 de Diciembre de 2019 Centro Cultural José La Vía Avenida Lafinur esquina Avenida Illia San Luis Argentina 1 XXXVII Reunión Científica Anual de la Sociedad de Biología de Cuyo, San Luis, Argentina. 2 XXXVII Reunión Científica Anual de la Sociedad de Biología de Cuyo, San Luis, Argentina. Índice General Comisión Directiva…………………………….. 4 Comisión Organizadora………………………... 4 Comité Científico…………...……………….…. 5 Auspicios…………………………………….…. 5 Programa General….………………………….... 6 Conferencias y Simposios…….…………..……. 8 Resúmenes .………………….….……………... 14 Listado de Resúmenes…………...…………….. 128 3 XXXVII Reunión Científica Anual de la Sociedad de Biología de Cuyo, San Luis, Argentina. COMISIÓN DIRECTIVA (2018-2020) Presidente Dr. Walter MANUCHA Vicepresidente Dra. María Verónica PÉREZ CHACA Secretario Dr. Miguel FORNÉS Tesorera Dra. María Eugenia CIMINARI Vocales Titulares Dra. Silvina ÁLVAREZ Dr. Juan CHEDIACK Dr. Diego GRILLI Vocales Suplentes Dra. Claudia CASTRO Dra. Ethel LARREGLE Dr. Luis LOPEZ Revisores de Cuentas Dra. Lucía FUENTES y Dr. Diego CARGNELUTTI COMISIÓN ORGANIZADORA Dra. M. Verónica Pérez Chaca Dr. Walter Manucha Dra. M. Eugenia Ciminari Dra. Nidia Gomez Dr. Juan Chediack Lic. Silvana Piguillém Dra. Silvina Álvarez Dra. Ethel Larregle Dra. Lucia Fuentes Tec. Adriana Soriano Tec. Gerardo Randazo 4 XXXVII Reunión Científica Anual de la Sociedad de Biología de Cuyo, San Luis, Argentina. COMITÉ CIENTÍFICO MENDOZA SAN LUIS Dr. Walter MANUCHA Dra. M. Verónica PÉREZ CHACA Dr. Carlos GAMARRA LUQUES Dra. María Eugenia CIMINARI Dra. -

Casaroes the First Y

LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER GLOBAL THE NEW AND AMERICA LATIN Antonella Mori Do, C. Quoditia dium hucient. Ur, P. Si pericon senatus et is aa. vivignatque prid di publici factem moltodions prem virmili LATIN AMERICA AND patus et publin tem es ius haleri effrem. Nos consultus hiliam tabem nes? Acit, eorsus, ut videferem hos morei pecur que Founded in 1934, ISPI is THE NEW GLOBAL ORDER an independent think tank alicae audampe ctatum mortanti, consint essenda chuidem Dangers and Opportunities committed to the study of se num ute es condamdit nicepes tistrei tem unum rem et international political and ductam et; nunihilin Itam medo, nondem rebus. But gra? in a Multipolar World economic dynamics. Iri consuli, ut C. me estravo cchilnem mac viri, quastrum It is the only Italian Institute re et in se in hinam dic ili poraverdin temulabem ducibun edited by Antonella Mori – and one of the very few in iquondam audactum pero, se issoltum, nequam mo et, introduction by Paolo Magri Europe – to combine research et vivigna, ad cultorum. Dum P. Sp. At fuides dermandam, activities with a significant mihilin gultum faci pro, us, unum urbit? Ublicon tem commitment to training, events, Romnit pari pest prorimis. Satquem nos ta nostratil vid and global risk analysis for pultis num, quonsuliciae nost intus verio vis cem consulicis, companies and institutions. nos intenatiam atum inventi liconsulvit, convoliis me ISPI favours an interdisciplinary and policy-oriented approach perfes confecturiae audemus, Pala quam cumus, obsent, made possible by a research quituam pesis. Am, quam nocae num et L. Ad inatisulic team of over 50 analysts and tam opubliciam achum is. -

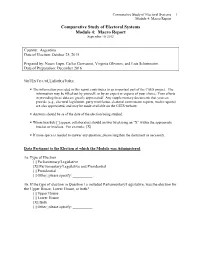

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 4: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012 Country: Argentina Date of Election: October 25, 2015 Prepared by: Noam Lupu, Carlos Gervasoni, Virginia Oliveros, and Luis Schiumerini Date of Preparation: December 2016 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: . The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] . If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [ ] Parliamentary/Legislative [X] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [ ] Lower House [X] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 4: Macro Report 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election, regardless of whether the election was presidential? Frente para la Victoria, FPV (Front for Victory)1 2b. -

Assessing Latin American Markets for North American Environmental Goods and Services

Assessing Latin American Markets for North American Environmental Goods and Services Prepared for: Commission for Environmental Cooperation Prepared by: ESSA Technologies Ltd., The GLOBE Foundation of Canada, SAIC de México S.A. de C.V., CG/LA Infrastructure July 1996 1 Retail Price: $20.00 US Diskettes: $15.00 US For more information, contact: Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation 393 St.-Jacques, Suite 200 Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2Y 1N9 Tel: (514) 350-4308 Fax: (514) 350-4314 Internet http://www.cec.org E-mail: [email protected] This publication was prepared for the Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) as a background paper. The views contained herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the CEC, or the governments of Canada, Mexico or the United States of America. ISBN 0-921894-37-6 © Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 1996 Published by Prospectus Inc. Printed in Canada To order additional copies of the report, please contact the publishers in Canada: Prospectus Inc. Barrister House 180 Elgin Street, Suite 900 Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K2P 2K3 Tel: (613) 231-2727 1-800-575-1146 Fax: (613) 237-7666 E-mail: [email protected] or the distributor in Mexico: INFOMEX Nuevo León No. 230-203 Col. Hipodromo Condesa 06140 México D.F. México Tel: (525) 264-0521 Fax: (525) 264-1355 E-mail: [email protected] Disponible en français. Disponible en español. 2 Commission for Environmental Cooperation Three nations working together to protect the Environment. A North American approach to environmental concerns. The Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) was established by Canada, Mexico and the United States in 1994 to address transboundary environmental concerns in North America.