Documento De Trabajo Opex 99-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chiba University Overview Brochure (PDF)

CHIBA UNIVERSITY 2020 2021 21 0 2 - 20 0 2 20 0 2 Contents 01 Introduction 01-1 A Message from the President ................................................................................................. 3 01-2 Chiba University Charter ........................................................................................................... 4 01-3 Chiba University Vision ............................................................................................................... 6 01-4 Chiba University Facts at a Glance .......................................................................................... 8 01-5 Organization Chart ....................................................................................................................... 10 02 Topic 02-1 Enhanced Network for Global Innovative Education —ENGINE— ................................. 12 02-2 Academic Research & Innovation Management Organization (IMO) .......................... 14 02-3 WISE Program (Doctoral Program for World-leading Innovative & Smart Education) ........................................................................................................................ 15 02-4 Creating Innovation through Collaboration with Companies ......................................... 16 02-5 Institute for Global Prominent Research .............................................................................. 17 02-6 Inter-University Exchange Project .......................................................................................... 18 02-7 Frontier -

Vol. 24 3/2018 Revista Gaceta Laboral Vol

ppi 201502ZU4639 Esta publicación científica en formato digital es continuidad de la revista impresa Depósito Legal: pp 199102ZU43 / ISSN:1315-8597 Vol. 24 3/2018 Revista Gaceta Laboral Vol. 24, No. 3 (2018): 232-253 Universidad del Zulia (LUZ) • ISSN 1315-8597 Organizaciones sindicales y movimientos sociales del mundo del trabajo durante el gobierno de Mauricio Macri (Argentina 2015-2017)1 Esteban Iglesias Mg. en Sociología y Ciencia Política. Dr. en Ciencia Política. Profesor Titular de Sociología Política de la Facultad de Ciencia Política y Director del Centro de Estudios Comparados de la Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Argentina. Investigador de Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología. Correo Electrónico: [email protected] Resumen Desde la restauración democrática en Argentina es posible determinar un nue- vo punto de inflexión histórica caracterizado por la asunción al gobierno na- cional de una fuerza política de derecha -liderada por Propuesta Republicana, PRO- con un proyecto socio-cultural que irradia transformaciones en el modo de gestionar el estado y, a su vez, en el funcionamiento de la sociedad. Esto ubica a las organizaciones del mundo del trabajo en un espacio privilegiado de análisis, el que se ve atravesado por los rasgos distintivos con que los miem- bros del gobierno gestionan el Estado y la dinámica del conflicto social. En este marco de preocupaciones, este trabajo tiene como objetivo principal describir el conjunto de relaciones que establecieron determinadas organizaciones sin- dicales y movimientos sociales con una fuerza política de derecha que asumió el gobierno, PRO. En este sentido, fue posible observar diferentes tipos de in- teracciones: 1. -

En Torno a Los Modos Actuales De Organización Y Participación Política Juvenil: El Caso De La Tosco En El Movimiento Evita Trabajo Y Sociedad, Núm

Trabajo y Sociedad E-ISSN: 1514-6871 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Argentina Bard Wigdor, Gabriela; Rasftopolo, Alexis En torno a los modos actuales de organización y participación política juvenil: el caso de La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita Trabajo y Sociedad, núm. 23, 2014, pp. 307-323 Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Santiago del Estero, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=387334695017 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Trabajo y Sociedad Sociología del trabajo – Estudios culturales – Narrativas sociológicas y literarias NB - Núcleo Básico de Revistas Científicas Argentinas (Caicyt-Conicet) Nº 23, Invierno 2014, Santiago del Estero, Argentina ISSN 1514-6871 - www.unse.edu.ar/trabajoysociedad En torno a los modos actuales de organización y participación política juvenil: el caso de La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita On current modes of organization and youth political participation: the case of The Tosco in Evita Movement Cerca atuais modos de organização e participação política dos jovens: o caso da La Tosco em Movimento Evita Gabriela Bard Wigdor y Alexis Rasftopolo* Recibido 15-6-13 Recibido con modificaciones: 29-8-13 Aceptado: 2-9-13 RESUMEN Luego de años de hegemonía neoliberal en la Argentina, a partir del 2003, se ha producido un cambio de modelo de gobierno que propone un Estado con fuerte intervención en la economía y producción de políticas públicas de carácter social. -

English Military Review November-December 2018 Allgeyer

THE PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL OF THE U.S. ARMY NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2018 Partnerships and Complexities in Africa Kuhlman, p6 Hidden Paterns of Tought in War Schwandt, p18 Using “Stryker” in Doctrine Allgeyer, p30 Space-Land Batle Brown, p120 THE PROFESSIONAL JOURNAL OF THE U.S. ARMY November-December 2018, Vol. 98, No. 6 Professional Bulletin 100-18-11/12 Authentication no.1829106 Commander, USACAC; Commandant, CGSC; DCG for Combined Arms, TRADOC: Lt. Gen. Michael D. Lundy, U.S. Army Provost, Army University, CGSC: Brig. Gen. Scot L. Efandt, U.S. Army Director and Editor in Chief: Col. Katherine P. Gutormsen, U.S. Army Managing Editor: William M. Darley, Col., U.S. Army (Ret.) Editorial Assistant: Linda Darnell Operations Ofcer: Maj. David B. Rousseau, U.S. Army Senior Editor: Jefrey Buczkowski, Lt. Col., U.S. Army (Ret.) Writing and Editing: Beth Warrington; Crystal Bradshaw-Gonzalez, contractor Graphic Design: Arin Burgess Cover photo: Soldiers from the 1st Batalion, 124th Infantry Regi- Webmasters: Michael Serravo; James Crandell, contractor Editorial Board Members: Command Sgt. Maj. Eric C. Dostie—Army University; ment, assigned to Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa, make Col. Rich Creed—Director, Combined Arms Doctrine Directorate; Dr. Robert their way across a portion of the mountain obstacle course 10 Octo- Baumann—Director, CGSC Graduate Program; Dr. Lester W. Grau—Director of ber 2016 as part of the fnal day of the French Marines Desert Surviv- Research, Foreign Military Studies Ofce; John Pennington—Chief, Publishing al Course at Arta Plage, Djibouti. As part of the course, the soldiers Division, Center for Army Lessons Learned; Col. -

En Torno a Los Modos Actuales De Organización Y Participación Política Juvenil: El Caso De La Tosco En El Movimiento Evita

En torno a los modos actuales de organización y participación política juvenil: el caso de La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita On current modes of organization and youth political participation: the case of The Tosco in Evita Movement Cerca atuais modos de organização e participação política dos jovens: o caso da La Tosco em Movimento Evita Gabriela BARD WIGDOR* y Alexis RASFTOPOLO**1 RESUMEN Luego de años de hegemonía neoliberal en la Argentina, a partir del 2003, se ha producido un cambio de modelo de gobierno que propone un Estado con fuerte intervención en la economía y producción de políticas públicas de carácter social. En este contexto, las organizaciones que emergieron con fuerza en los 90 sobre el eje de “trabajo digno” (movimientos piqueteros, fabricas y empresas recuperadas, etc.) y de rechazo hacia la corrupción y representación política, contenida en el “que se vayan todos” (asambleas barriales y puebladas), se transformaron en organizaciones con nuevas lógicas, de fuerte participación juvenil, que se identifican con el Estado y experimentan nuevos modos de hacer política. En este artículo, tomamos un caso concreto de Córdoba capital: la organización territorial La Tosco en el Movimiento Evita, con la intención de analizar, comprender e intentar explicar, los modos actuales de organización política tanto a nivel de los movimientos sociales como en su relación con el Estado. Nuestro supuesto de trabajo es que los cambios ocurridos a partir del 2003, condicionan los nuevos modos de hacer política y de organizarse al interior de -

Instructional Technology Distance Learning

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INSTRUCTIONAL TECHNOLOGY AND DISTANCE LEARNING March 2012 Volume 9 Number 3 Editorial Board Donald G. Perrin Ph.D. Executive Editor Elizabeth Perrin Ph.D. Editor-in-Chief Brent Muirhead Ph.D. Senior Editor Muhammad Betz, Ph.D. Editor ISSN 1550-6908 International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning PUBLISHER'S DECLARATION Research and innovation in teaching and learning are prime topics for the Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning (ISSN 1550-6908). The Journal was initiated in January 2004 to facilitate communication and collaboration among researchers, innovators, practitioners, and administrators of education and training involving innovative technologies and/or distance learning. The Journal is monthly, refereed, and global. Intellectual property rights are retained by the author(s) and a Creative Commons Copyright permits replication of articles and eBooks for education related purposes. Publication is managed by DonEl Learning Inc. supported by a host of volunteer editors, referees and production staff that cross national boundaries. IJITDL is committed to publish significant writings of high academic stature for worldwide distribution to stakeholders in distance learning and technology. In its first six years, the Journal logged over six million page views and more than one million downloads of Acrobat files of monthly journals and eBooks. Donald G. Perrin, Executive Editor Elizabeth Perrin, Editor in Chief Brent Muirhead, Senior Editor Muhammad Betz, Editor March -

Let's Not Talk About It

PolandArgentina essay 77 by Mercedes Barros LET’S NOT and Natalia Martínez TALK ABOUT IT Feminism and populism in Argentina ince the emergence of #NiUnaMenos [Not One Less] in marking our differences — we will go on to explain the conditions 2015, feminism has become widespread in Argentina.1 that from our perspective enabled feminism to become popular. Nowadays, actions such as to identify oneself as a Firstly, we will point to the relationship that feminist groups feminist, to cite her slogans, to use her handkerchiefs, have established with human rights activism since the early 80s. to hold her flags, are no longer conceived as minority, elitist or Later, we will direct attention to the effects of displacement re- radicalized practices. Feminisms are becoming more common. sulting from the political articulation that took place in the new They slip into every day and ordinary experiences, and advo- millennium between human rights groups and the political force cates and allies of their causes appear in the most unlikely places that was in government for almost a decade, Kirchnerism. As we and contexts. There are feminists in political parties, in the state, will show, this political process decisively affected the feminist in unions, in universities, in secondary schools, in companies, movements and the positions they hold in the social and politi- in religious groups, among housewives and among the Madres cal arena at the present time. y Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo [Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo].2 As one of its flags usually holds, there are “femi- Dress for success: nists everywhere”. -

CURRICULUM VITAE H. W. Perry, Jr. the University of Texas School Of

CURRICULUM VITAE H. W. Perry, Jr. The University of Texas School of Law 727 East Dean Keeton St. Austin, TX 78705 [email protected] (512) 232-1852 Education Ph.D., The University of Michigan, Political Science, 1987 Legal Coursework at The University of Michigan Law School M.A., The University of Michigan, Political Science B.A., with honors, Southern Methodist University, Political Science, Social Sciences, 1974 Academic Appointments University Distinguished Teaching Professor Associate Professor of Law, School of Law, 2000-present Associate Professor of Government, College of Liberal Arts, 1994-present The University of Texas at Austin Interdisciplinary professor, School of Law, The University of Texas at Austin, 1997-2000 Associate Professor, Department of Government, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University, 1990-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University, 1986-1990 Instructor, Department of Political Science, College of Arts and Sciences, Washington University, 1983-1986 Lecturer, Department of Political Science, The University of Michigan, Spring/Summer 1981; Summer 1982 Visiting Appointments Distinguished Visiting Professor, LaTrobe Law School, Melbourne, Australia, June 2017, 2018 Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Centre for Law, Governance and Public Policy, Bond University, Queensland, Australia, June, 2010 Astor Visiting Lecturer, Centre for Socio-legal Studies, Oxford University, June 2000 H. W. Perry, Jr. 2 Non-academic Director of Development, S.M.U. School of Law, 1975-1977 Employment Assistant Director of Development, S.M.U., 1974-1975 Selected Administrative Founding and current Director, Combined JD/Ph.D. program in law and Responsibilites, U.T. politics . Co-Principal Investigator, Ford Foundation Grant for Difficult Dialogs Director, Texas-Oxford Law Faculty interchange 2000-2007 Chair, Public Law subfield 1994-2005 Director, Democracy in the Third Millennium Program 1997-2000 Research Areas U. -

Education and Technology in Mexico and Latin America: Outlook and Challenges

http://rusc.uoc.edu doSSIEr Education and Technology in Mexico and Latin America: Outlook and Challenges. Introduction Submitted in: May 2013 Accepted in: May 2013 Published in: July 2013 Recommended citation ONTIVEROS, Margarita; CANAY, José Raúl (2013). “Education and Technology in Mexico and Latin Ame- rica: Outlook and Challenges. Introduction”. In: “Education and Technology in Mexico and Latin Ameri- ca: Outlook and Challenges” [online dossier]. Universities and Knowledge Society Journal (RUSC). Vol. 10, No 2. pp. 407-413. UOC. [Accessed: dd/mm/yy]. <http://rusc.uoc.edu/ojs/index.php/rusc/article/view/v10n2-ontiveros-canay/v10n2-ontiveros-ca- nay-en> <http://dx.doi.org/10.7238/rusc.v10i2.1848> ISSN 1698-580X Abstract With an increasing number of young people reaching university entrance age, the demographic reality of Latin American countries is changing the face of their traditional higher education spaces. The impact is driving institutions to seek effective solutions, and technology has been identified as a ‘way forward’ in terms of offering education to the growing population of young people who want it. Technology- mediated education must therefore help to improve Latin American citizens’ quality of life. In Mexico, and since 2010, the National System of Distance Education (SINED) – an initiative led by universities interested in strengthening education mediated by information and communication technologies (ICTs) – has been exploring ways to incorporate these tools into the evolution of Mexi- can and, by extension, Latin American universities. This monographic Dossier, produced in conjunction with RUSC. Universities and Knowledge So- ciety Journal, is part of the SINED’s effort to progress towards generating information, documentation and materials to support the academic community involved in ICTs and innovation from a number of angles, including use, learning and research. -

The Miciina Hairriccibie Registration Shows 2 Guys for Each

Registration Shows 2 Guys For Each Girl University College coeds should Juniors 665 1205 uomen. For the 283 senior busi- Of the 221 students in the tcring the School of Medicine, classes, but receive no credit, Seniors 392 801 <lo well this semester in "The Unclassified 981 663 ness majors, there are only 27 School of Engineering, only 5 only 20 are women. number 75. Auditors 36 39 women. are women. Picken' and Chosen' of Males" B> March 10 there «err Specie] non-credit courses, Reason-there Total 3,566 5,681 Illl through 202. The School of Music has the In addition to these under- I.L'.Vi graduate students enrol- programs and institutes contain arc men to 1.750 graduates, 3,375 women. The School of Arts and lowest enrollment with 28 men there ere 994 students led Hut linal figures have not 1,328 evening students The en- report Registrar The released by Seeinces has 1,157 day students and 20 women. classified as new freshmen, trans- set been released. I'nlike any rollment m this area is still open. George Smith shows the follow- in; fers, and re-admitted students. Other school, the evening grad- iitul evening students. Of Only in the School of Educa- Summary totals for Srnnj enrollment are: ing for lioth daytime and eve- ii ile students these 775 .'ire males. tion do men have the advantage The Law School enrollment outnumber the Undergraduates 9247 ning undergraduate students: davtimcrs 702 to 184, with al- Graduates and professional students 1872 I Ii.-i .- .m 488 junior in with 478 males to 1,199 females reached 320 this semester. -

Militancia Juvenil Y Gestión Estatal En El Movimiento Evita De Argentina (2005-2015)

Ánfora ISSN: 0121-6538 ISSN: 2248-6941 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma de Manizales Colombia Tirando viejos por la ventana? Militancia juvenil y gestión estatal en el Movimiento Evita de Argentina (2005-2015) Longa, Francisco Tirando viejos por la ventana? Militancia juvenil y gestión estatal en el Movimiento Evita de Argentina (2005-2015) Ánfora, vol. 25, núm. 45, 2018 Universidad Autónoma de Manizales, Colombia Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=357857619022 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v25.n45.2018.518 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional. PDF generado a partir de XML-JATS4R por Redalyc Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Francisco Longa. Tirando viejos por la ventana? Militancia juvenil y gestión estatal en el Movimie... Investigación Tirando viejos por la ventana? Militancia juvenil y gestión estatal en el Movimiento Evita de Argentina (2005-2015) Pulling the old out the window? Youth militancy and state management in the Evita Movement of Argentina (2005-2015) Jogando idosos pela janela? Militância juvenil e gestão do Estado no Movimento Evita da Argentina (2005-2015) Francisco Longa DOI: https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v25.n45.2018.518 Universidad Nacional de La Plata , Argentina Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? [email protected] id=357857619022 Recepción: 12 Junio 2017 Aprobación: 01 Marzo 2018 Resumen: Objetivo: analizar la experiencia del Movimiento Evita de Argentina para comprender los sentidos que en el movimiento se construyen en torno a la noción de ‘juventud’, y los accesos y restricciones de dicha juventud a las estructuras del movimiento. -

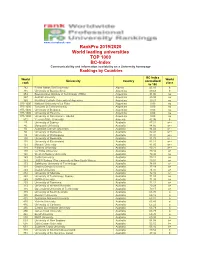

Rankpro 2019/2020 World Leading Universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and Information Availability on a University Homepage Rankings by Countries

www.cicerobook.com RankPro 2019/2020 World leading universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and information availability on a University homepage Rankings by Countries BC-Index World World University Country normalized rank class to 100 782 Ferhat Abbas Sétif University Algeria 45.16 b 715 University of Buenos Aires Argentina 49.68 b 953 Buenos Aires Institute of Technology (ITBA) Argentina 31.00 no 957 Austral University Argentina 29.38 no 969 Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina Argentina 20.21 no 975-1000 National University of La Plata Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 Torcuato Di Tella University Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Belgrano Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Palermo Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of San Andrés - UdeSA Argentina 0.00 no 812 Yerevan State University Armenia 42.96 b 27 University of Sydney Australia 87.31 a++ 46 Macquarie University Australia 84.66 a++ 56 Australian Catholic University Australia 84.02 a++ 80 University of Melbourne Australia 82.41 a++ 93 University of Wollongong Australia 81.97 a++ 100 University of Newcastle Australia 81.78 a++ 118 University of Queensland Australia 81.11 a++ 121 Monash University Australia 81.05 a++ 128 Flinders University Australia 80.21 a++ 140 La Trobe University Australia 79.42 a+ 140 Western Sydney University Australia 79.42 a+ 149 Curtin University Australia 79.11 a+ 149 UNSW Sydney (The University of New South Wales) Australia 79.01 a+ 173 Swinburne University of Technology Australia 78.03 a+ 191 Charles Darwin University Australia 77.19