Planning for Age-Friendly Cities: Towards a New Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborative Planning for Megacities in Developing Countries: Reinventing Urban Democracy

COLLABORATIVE PLANNING FOR MEGACITIES IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: REINVENTING URBAN DEMOCRACY Soyun Leem 5884518 April 2, 2012 Public and International Affairs Faculty of Graduates and Postdoctoral Studies University of Ottawa TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………...... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………. 2 1.1 Research Question …………………………………………………………… 3 1.2 Rationales for Research …………………………………………………........ 3 1.3 Review of Concepts ………………………………………………………….. 4 1.4 Research Paper Layout ………………………………………………………. 7 2. URBANIZATION IN THE DEVELOPING COUNTRIES …………………......... 8 2.1 Urbanization Trends and Megacities in Developing Countries ……………… 8 2.2 Challenges of Megacities in Developing Countries ………………………….. 11 3. CHALLENGES OF TRADITIONAL PLANNING PROCESS …………………. 15 3.1 Planning Challenges Facing Megacities in Developing Countries …………. 16 3.2 Nature of the Traditional Planning Process ………………………………….. 18 4. NEGATIVE CONSEQUENCES OF THE TRADITIONAL PLANNING APPROACH IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES ………………………...…….……. 21 4.1 Deficient Flow of Information and Knowledge Exchange …………………... 21 4.2 Poor Ownership, Legitimacy and Enforcement Power ……………………. 22 4.3 Lack of Social Cohesion and Sense of Community ………………….……… 23 4.4 Lack of Accountability and Transparency …………………………….……... 23 4.5 Failure of the Traditional Master Planning Approach .…….………………. 24 5. COLLABORATIVE MODEL OF PLANNING – PUBLIC PARTICIPATION … 25 5.1 Benefits of Participatory Planning for Megacities in Developing Countries … 26 6. CASE STUDIES………………………………………………………………..……… -

Liste Des Finalistes En Télévision

Liste des finalistes en télévision MONTRÉAL | TORONTO, 19 janvier 2016 Best Dramatic Series Sponsor | Innovate By Day 19-2 Bravo! (Bell Media) (Sphere Media Plus, Echo Media) Jocelyn Deschenes, Virginia Rankin, Bruce M. Smith, Luc Chatelain, Greg Phillips, Saralo MacGregor, Jesse McKeown Blackstone APTN (Aboriginal Peoples Television Network) (Prairie Dog Film + Television) Ron E. Scott, Jesse Szymanski, Damon Vignale Motive CTV (Bell Media) (Motive Productions III Inc., Lark Productions, Foundation Features) Daniel Cerone, Dennis Heaton, Louise Clark, Rob Merilees, Erin Haskett, Rob LaBelle, Lindsay Macadam, Brad Van Arragon, Kristin Lehman, Sarah Dodd Saving Hope CTV (Bell Media) (Entertainment One, ICF Films) Ilana Frank, David Wellington, Adam Pettle, Morwyn Brebner, John Morayniss, Margaret O'Brien, Lesley Harrison X Company CBC (CBC) (Temple Street Productions) Ivan Schneeberg, David Fortier, Andrea Boyd, Mark Ellis, Stephanie Morgenstern, Bill Haber, Denis McGrath, Rosalie Carew, John Calvert Best Comedy Series Mr. D CBC/City (CBC / Rogers Media) (Mr. D S4 Productions Ltd., Mr. D S4 Ontario Productions Ltd.) Michael Volpe, Gerry Dee PRIX ÉCRANS CANADIENS 2016 | Liste des finalistes en télévision | 1 Mohawk Girls APTN (APTN) (Rezolution Pictures Inc.) Catherine Bainbridge, Christina Fon, Linda Ludwick, Ernest Webb, Tracey Deer, Cynthia Knight Schitt's Creek CBC (CBC) (Not A Real Company Productions Inc.) Eugene Levy, Daniel Levy, Andrew Barnsley, Fred Levy, Ben Feigin, Mike Short, Kevin White, Colin Brunton Tiny Plastic Men Super -

Popular Education for Racial and Environmental

PA 5262 Neighborhood Revitalization Theories and Strategies CREATE Initiative Popular Education for Environmental and Racial Justice in Minneapolis Prepared By Stefan Hankerson, Kelsey Poljacik, Rebecca Walker, Alexander Webb, Aaron Westling Acknowledgements This report was prepared by Stefan Hankerson, Kelsey Poljacik, Rebecca Walker, Alexander Webb, and Aaron Westling for the University of Minnesota’s CREATE Initiative. This report is a semester-long project for the Fall 2019 PA 5262 Neighborhood Revitalization Theories and Strategies class at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota. Listed below are the people who guided and instructed us through this process, and gave us the opportunity to work on this project. Course Instructors Shannon Smith Jones, Hope Community, Inc., Executive Director Will Delaney, Hope Community, Inc., Associate Director Project Client Dr. Kate Derickson, CREATE Initiative, University of Minnesota, Co-Director Technical Assistance Mira Klein, CREATE Initiative, University of Minnesota, Research Associate Kevin Ehrman-Solberg, CREATE Initiative and Mapping Prejudice, University of Minnesota, Research Associate 2 Table of Contents Prepared By 1 Acknowledgements 2 Course Instructors 2 Project Client 2 Technical Assistance 2 Table of Contents 3 Executive Summary 4 Popular Education for Environmental and Racial Justice in Minneapolis 5 Client: The CREATE Initiative 5 Our Project Goals 5 Background 6 How We Got Here 6 Minneapolis-Specific Context 7 Environmental Justice and Green Gentrification -

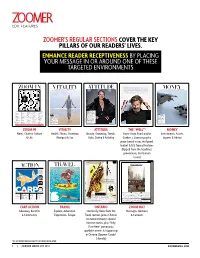

Enhance Reader Receptiveness by Placing Your Message in Or Around One of These Targeted Environments ZOOMER's REGULAR SECTIONS

edit feaTURES ZOOMER’S REGULAR SECTIONS COVER THE KEY PILLARS OF OUR READERS’ LIVES. ENHANCE READER RECEPTIVENESS BY PLACING YOUR MESSAGE IN OR AROUND ONE OF THESE TARGETED ENVIRONMENTS AS AN ACTOR, I’VE REALLY GONE ABOUT NEWS CHATTER CULTURE LIFE EDITOR KIM IZZO BEAUTy grooming trends sTyle EDITor kim ZZOI TRYING TO AS MUCH AS I ZOOM IN VITALITYHEALth fitneSs nutrition sex EDITor vivian vASSOS ATTITUDE MIX UP MY ROLES INVESTMENTsMONEY aSSETs experTs advice EDITor peter muggeridge CAN. IT KEEPS IT INTERESTING FOR ME AND ALSO, HOPEFULLY, PLEASANTLY CONFUSES THE AUDIENCE SO THEY CAN LET ME “BECOME DIFFERENT CHARACTERS” —Je Bridges I’m FIERCELY TKTKTK MAINLY ABOUT MONEY NOT ALL, BUT MOST, OF THE CLUES REFER TO TKTKTKTKTK PROTECTIVE OF ACROSS 40 For each 64 Universal Time 7 Nickel, the element 50 Russian monetary unit EVERY INCH OF THIS 1 European currency 41 US postal code 65 Entice 8 Money 53 Office of 4 Original sum invested 42 Tall rounded vase 66 “On the other hand” in text 9 List deductions on tax EconomicOpportunity THING AND CREATING 12 The root of all evil 43 Greek speak return 55 Profit 16 Gain in value 44 A tax paid in Canada 69 Suffix for forming verbs 10 Of money 57 Chimp SOMETHING THAT HAS ____ THERE IS 17 America 45 Each 70 Each 11 Entice 58 Writer Cummings SEX AND SIZZLE” ONLY ONE SIDE OF 19 Anguish 46 Ancestor of Saul according 71 Symbol for the chemical 12 Time for repayment 62 Movemvf cash HEALTH IS —Robin Kay, president of the 20 Tenant’s payment to I Samuel antimony 13 Northwest 67 A type of rock containing THE MARKET, AND 21 Frozen water 48 Body of water 72 Driving Under the Influence 14 Geologic time minerals om Fashion Design Council of THE THING THAT C 22 Asset deposited to ensure 50 Color of ink indicating a 74 A county in Kentucky or 15 Annual (report) 68 Opposite of she Canada, about LG Fashion IT IS NOT THE repayment deficit the surname of well-known 18 Social Insurance Number 71 The tax on items MAKES YOU FEEL Is BULL SIDE OR THE 24 Not applicable 51 Hernando ____ Soto American militia activist. -

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING in CANADA Thursday, June 1, 2006 Volume 14, Number 2 Page One of Three

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING IN CANADA Thursday, June 1, 2006 Volume 14, Number 2 Page One of Three DO NOT RETRANSMIT THIS ADIO: MOJO Sports Radio (CHMJ) Vancouver, owned by Corus, PUBLICATION BEYOND YOUR will see 14 people out of a job come this weekend. On Monday, June RECEPTION POINT R5, CHMJ begins airing continuous traffic reports during the day and the best of talk from sister station CKNW Vancouver at other times. Howard Christensen, Publisher Broadcast Dialogue New ID is AM730 Continuous Drive Time Traffic and the Best of Talk and 18 Turtle Path will also feature the Vancouver Whitecaps and Giants and Seattle Lagoon City ON L0K 1B0 Seahawks games. Among those out of work are CKNW Sports Director JP (705) 484-0752 [email protected] McConnell and MOJO personalities John McKeachie, Bob Marjanovich, www.broadcastdialogue.com Jeff Paterson and Blake Price. Seen as the 100% CANADIAN As dagger to MOJO’s heart Canada’s public was CHUM-owned Team 1040 Vancouver’s acquisition of broadcaster, CBC offers all Canadians Vancouver Canucks radio rights, owned for decades by broadcasting services CKNW. And earlier, Team 1040 took play-by-play rights to that reflect and celebrate our country’s diverse the BC Lions away from Corus... Y101 (CKBY-FM) Ottawa heritage, culture and stories. is in the midst of a three-day Radiothon – May 31 to June 2 SENIOR BROADCAST TECHNOLOGIST – for the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO). th This is the 8 annual Y101 Country Cares Challenge for Your primary role will be to ensure the CHEO and organizers say they expect to break the $1- maintenance of broadcasting equipment and million dollar mark at this year’s event.. -

A Discursive Project of Low-Carbon City in Shenzhen, China

Anti-Carbonism or Carbon Exceptionalism: A Discursive Project of Low-Carbon City in Shenzhen, China Yunjing Li Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 2019 Yunjing Li All rights reserved ABSTRACT Anti-Carbonism or Carbon Exceptionalism: A Discursive Project of Low-Carbon City in Shenzhen, China Yunjing Li As the role of cities in addressing climate change has been increasingly recognized over the past two decades, the idea of a low-carbon city becomes a dominant framework to organize urban governance and envision a sustainable urban future. It also becomes a development discourse in the less developed world to guide the ongoing urbanization process. China’s efforts toward building low-carbon cities have been inspiring at first and then obscured by the halt or total failure of famous mega-projects, leading to a conclusion that Chinese low-carbon cities compose merely a strategy of green branding for promoting local economy. This conclusion, however, largely neglects the profound implications of the decarbonization discourse for the dynamics between the central and local governments, which together determine the rules and resources for development practices. The conclusion also hinders the progressive potentials of the decarbonization discourse in terms of introducing new values and norms to urban governance. This dissertation approaches “low-carbon cities” as a part of the decarbonization -

The Sustainability of a City

THE SUSTAINABILITY OF A CITY A case study over sustainable urban planning in Örebro municipality, Sweden Vincent Mossberg Supervisor: Erik Hysing Date for seminar: 2018-06-01 Master’s thesis in political science Independent work, 15 credits Master’s thesis Vincent Mossberg Master’s thesis Vincent Mossberg Abstract The trend of urbanization has been going on for more than a century and city planning has always been a big part of planning theory. In the debate of how urban planning should be conducted there is a long history of what makes up a sustainable city, which started as early as in the end of the nineteenth century. There are many theories and debates about what is the most sustainable urban form and there are also diverse opinions about the different conflicts surrounding sustainability and how to deal with these conflicts. The purpose of this thesis is to research what urban form is promoted in Örebro municipality and what sustainability conflicts are connected to the municipality’s urban form. The purpose is also to research how these conflicts are dealt with. The research questions for this thesis are 1) What urban form is primarily promoted in Örebro municipality? 2) What sustainability conflicts are connected to this urban form in Örebro municipality? and 3) How are these sustainability conflicts dealt with? The research design in this thesis is a case study and there are two methods used in this thesis. First, a qualitative text analysis to answer the first and second question. The text analysis is complemented by interviews on the first and the second question, and on the third question the method used was only interviews. -

Shifting Approaches to Planning Theory: Global North and South

Urban Planning (ISSN: 2183–7635) 2016, Volume 1, Issue 4, Pages 32–41 DOI: 10.17645/up.v1i4.727 Article Shifting Approaches to Planning Theory: Global North and South Vanessa Watson School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics, University of Cape Town, 7701 Rondebosch, South Africa; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 23 August 2016 | Accepted: 29 November 2016 | Published: 6 December 2016 Abstract Planning theory has shifted over time in response to changes in broader social and philosophical theory as well as changes in the material world. Postmodernism and poststructuralism dislodged modernist, rational and technical approaches to planning. Consensualist decision-making theories of the 1980s took forms of communicative and collaborative planning, drawing on Habermasian concepts of power and society. These positions, along with refinements and critiques within the field, have been hegemonic in planning theory ever since. They are, in most cases, presented at a high level of abstraction, make little reference to the political and social contexts in which they are based, and hold an unspoken assumption that they are of universal value, i.e. valid everywhere. Not only does this suggest important research methodology errors but it also renders these theories of little use in those parts of the world which are contextually very different from theory origin—in most cases, the global North. A more recent ‘southern turn’ across a range of social science disciplines, and in planning theory, suggests the possibility of a foundational shift toward theories which acknowledge their situatedness in time and place, and which recognize that extensive global difference in cities and regions renders universalized theorising and narrow conceptual models (especially in planning theory, given its relevance for practice) as invalid. -

Rationality and Portability: Case Study Research in Practice

Rationality and portability: Case study research in practice Bo Bengtsson & Nils Hertting What general lessons can be learned from the study of single cases? This is one of the most controversial methodological issues in the social sciences. Elsewhere, we have proposed a logic of generalization from case studies using thinly rationalistic ideal-type social mechanisms (cf. Elster 1983) as a conceptual bridge to make the ndings from one case (to some extent) portable to other contexts (Bengtsson & Hertting 2014; cf. also Bengtsson & Ruonavaara 2011; 2017). In this chapter, we recapitulate the general logic behind such `rationalistic generalizations' and apply it to one exemplary and well- known case study: Bent Flyvbjerg's thorough investigation of planning processes in the Danish city of Aalborg, as presented in his book Rationality and Power. Democracy in Practice (1998). Flyvbjerg implies some generalizing ambition when he interprets the object of his study, the so-called Aalborg Project, as `a metaphor of modern politics, modern administration and planning, and modernity itself'. It is, however, unclear what logic of generalization Flyvbjerg has in mind more precisely, and in Bengtsson & Hertting 2014, we actually suggest that it may be in line with our model of generalization based on thinly rationalistic social mechanisms. In this chapter, we attempt to translate Flyvbjerg's argument into such terms. Purpose and outline The main purpose of the chapter is to test the fruitfulness of a logic of generalization based on thinly rationalistic ideal-type social mechanisms by applying it to the analysis of a case study that is largely actor-based but where the generalizing ambitions are not explicitly based on thin rationality. -

Press Release Contains "Forward-Looking Statements"

Tuesday, August 18, 2020 ZoomerMedia Limited Announces Close of Sale of Assets of Darwin CX Inc. (Toronto, Canada – August 18, 2020) Further to its media release dated May 18, 2020, ZoomerMedia Limited (“ZoomerMedia”) (TSXV: ZUM) is pleased to announce that it has closed the agreement (“Purchase Agreement”) for the sale of substantially all of the assets (“Darwin Assets”) of ZoomerMedia’s wholly-owned subsidiary Darwin CX Inc. (“Darwin”), ZoomerMedia’s proprietary subscription and membership management platform, to New York–based Irish Studio LLC (“Irish Studio”). The purchase price was $7,465,000 (CAD), consisting of $700,000 (CAD) received concurrently on signing of the Purchase Agreement, and $5,386,000 (CAD) in cash and a $1,280,000 promissory note of Irish Studio, subject to customary post-closing adjustments, which were received by ZoomerMedia on the closing date. “ZoomerMedia committed significant resources to creating Darwin in a space that hasn’t seen innovation in decades, so it’s not surprising that it developed into a competitive software platform in a short period of time. Darwin naturally complements Irish Studio's core business and they are better positioned to invest the additional resources necessary for long-term growth. The sale price is in line with our expectations, fetches good value for ZML shareholders, strengthens ZML's financial position, and allows us to focus our energy on growing our core media businesses focused on Canada’s 45plus demographic,” said ZoomerMedia Founder and CEO Moses Znaimer. The Special Relationship between ZoomerMedia and Darwin will not end with the sale. ZoomerMedia Chief Digital Officer and Darwin co-founder Omri Tintpulver will sit on Darwin’s Advisory Board, and the company’s operations will continue to be based at ZoomerMedia’s headquarters in Toronto’s Liberty Village for now. -

IJPHCS International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences Open Access: E-Journal E-ISSN : 2289-7577

IJPHCS International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences Open Access: e-Journal e-ISSN : 2289-7577. Vol. 5:No. 4 July/August 2018 PLANNING THEORIES IN PRIMARY HEALTH CARE PLANNING Zaahirah M.1, Puvanese Rebecca S.1, Faridah J.1, Fikri R.1, Saba A.1 Muhamad Hanafiah Juni2, Rosliza A.M.2* 1 MPH Candidates, Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia. 2 Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia. *Corresponding author: Dr Rosliza Abdul Manaf; email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Background: Primary care planning is part of national health plan. Literatures indicate that rationalism, incrementalism and mixed scanning planning theories were widely used in health planning. This paper aims to compare the three type of planning theories and its’ applications in Primary Health Care planning. Materials and Method: A scoping review was used in this study. Articles were identified using four databases namely Scopus, Google Scholar, PubMed and Science Direct. Three commonly used planning theories which include rational planning theory, incrementalism planning theory and mixed scanning theory and relevant countries Primary Health Care planning with the application of the theories were selected. Five countries from five articles were reviewed that were relevant and related to the above theories and its application in primary care. Only articles written in English within the last 15 years were included. Results: Rational planning is the most commonly practiced and the basis of all public planning. It enables list of alternatives or options and the best option is chosen based on the options that maximizes the optimum output. -

2011 AICP Review Course HISTORY and THEORY

2011 AICP Review Course HISTORY AND THEORY February 2011 Kelly O’Brien, AICP, PP, LEED AP Professional Development Officer of Exam Prep American Planning Association – New Jersey Chapter MAY 2011 AICP EXAM REVIEW HISTORY AND THEORY History and Theory (and Law) 15% • History of planning • Planning law • Theory of planning • Patterns of human settlement MAY 2011 AICP EXAM REVIEW HISTORY AND THEORY Primary functions of planning • improve efficiency of outcomes • counterbalance market failures - balance public and private interests • widen the range of choice - enhance consciousness of decision making • civic engagement - expand opportunity and understanding in community MAY 2011 AICP EXAM REVIEW HISTORY AND THEORY Professionalization of Planning 1901 NYC: “New Law” regulates tenement housing 1907 Hartford: first official & permanent local planning board 1909 – Washington DC: first planning association – National Conference on City Planning – Wisconsin: first state enabling legislation permitting cities to plan – Chicago Plan: Burnham creates first regional plan – Los Angeles: first land use zoning ordinance – Harvard School of Landscape Architecture: first course in city planning MAY 2011 AICP EXAM REVIEW HISTORY AND THEORY Pre-modern to New Urban Form 1682 Philadelphia plan Grid system & William Penn neighborhood parks Thomas Holme 1695 Annapolis plan Radiocentric Francis Nicholson 1733 Savannah Ward park system Oglethorpe 1790 Washington Grand, whole city plan Pierre L’Enfant 1852-1870 Paris Model for “City Beautiful” Napoleon III; Haussmann 1856 Central Park First major purchase of F L Olmsted Sr parkland 1869 Riverside, IL Model curved street FL Olmsted Sr “suburb” Calvert Vaux 1880 Pullman, IL Model industrial town George Pullman MAY 2011 AICP EXAM REVIEW HISTORY AND THEORY Philosophies and Movements Agrarian Philosophy 1800’S – Belief that a life rooted in agriculture is the most humanly valuable.