Choosing Among Beliefs and Reasoning About Choices Integrative Thinking Through the Prism of Theories of Rational Choice And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Des Finalistes En Télévision

Liste des finalistes en télévision MONTRÉAL | TORONTO, 19 janvier 2016 Best Dramatic Series Sponsor | Innovate By Day 19-2 Bravo! (Bell Media) (Sphere Media Plus, Echo Media) Jocelyn Deschenes, Virginia Rankin, Bruce M. Smith, Luc Chatelain, Greg Phillips, Saralo MacGregor, Jesse McKeown Blackstone APTN (Aboriginal Peoples Television Network) (Prairie Dog Film + Television) Ron E. Scott, Jesse Szymanski, Damon Vignale Motive CTV (Bell Media) (Motive Productions III Inc., Lark Productions, Foundation Features) Daniel Cerone, Dennis Heaton, Louise Clark, Rob Merilees, Erin Haskett, Rob LaBelle, Lindsay Macadam, Brad Van Arragon, Kristin Lehman, Sarah Dodd Saving Hope CTV (Bell Media) (Entertainment One, ICF Films) Ilana Frank, David Wellington, Adam Pettle, Morwyn Brebner, John Morayniss, Margaret O'Brien, Lesley Harrison X Company CBC (CBC) (Temple Street Productions) Ivan Schneeberg, David Fortier, Andrea Boyd, Mark Ellis, Stephanie Morgenstern, Bill Haber, Denis McGrath, Rosalie Carew, John Calvert Best Comedy Series Mr. D CBC/City (CBC / Rogers Media) (Mr. D S4 Productions Ltd., Mr. D S4 Ontario Productions Ltd.) Michael Volpe, Gerry Dee PRIX ÉCRANS CANADIENS 2016 | Liste des finalistes en télévision | 1 Mohawk Girls APTN (APTN) (Rezolution Pictures Inc.) Catherine Bainbridge, Christina Fon, Linda Ludwick, Ernest Webb, Tracey Deer, Cynthia Knight Schitt's Creek CBC (CBC) (Not A Real Company Productions Inc.) Eugene Levy, Daniel Levy, Andrew Barnsley, Fred Levy, Ben Feigin, Mike Short, Kevin White, Colin Brunton Tiny Plastic Men Super -

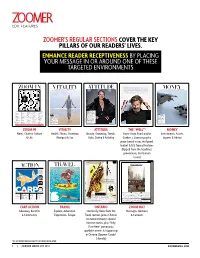

Enhance Reader Receptiveness by Placing Your Message in Or Around One of These Targeted Environments ZOOMER's REGULAR SECTIONS

edit feaTURES ZOOMER’S REGULAR SECTIONS COVER THE KEY PILLARS OF OUR READERS’ LIVES. ENHANCE READER RECEPTIVENESS BY PLACING YOUR MESSAGE IN OR AROUND ONE OF THESE TARGETED ENVIRONMENTS AS AN ACTOR, I’VE REALLY GONE ABOUT NEWS CHATTER CULTURE LIFE EDITOR KIM IZZO BEAUTy grooming trends sTyle EDITor kim ZZOI TRYING TO AS MUCH AS I ZOOM IN VITALITYHEALth fitneSs nutrition sex EDITor vivian vASSOS ATTITUDE MIX UP MY ROLES INVESTMENTsMONEY aSSETs experTs advice EDITor peter muggeridge CAN. IT KEEPS IT INTERESTING FOR ME AND ALSO, HOPEFULLY, PLEASANTLY CONFUSES THE AUDIENCE SO THEY CAN LET ME “BECOME DIFFERENT CHARACTERS” —Je Bridges I’m FIERCELY TKTKTK MAINLY ABOUT MONEY NOT ALL, BUT MOST, OF THE CLUES REFER TO TKTKTKTKTK PROTECTIVE OF ACROSS 40 For each 64 Universal Time 7 Nickel, the element 50 Russian monetary unit EVERY INCH OF THIS 1 European currency 41 US postal code 65 Entice 8 Money 53 Office of 4 Original sum invested 42 Tall rounded vase 66 “On the other hand” in text 9 List deductions on tax EconomicOpportunity THING AND CREATING 12 The root of all evil 43 Greek speak return 55 Profit 16 Gain in value 44 A tax paid in Canada 69 Suffix for forming verbs 10 Of money 57 Chimp SOMETHING THAT HAS ____ THERE IS 17 America 45 Each 70 Each 11 Entice 58 Writer Cummings SEX AND SIZZLE” ONLY ONE SIDE OF 19 Anguish 46 Ancestor of Saul according 71 Symbol for the chemical 12 Time for repayment 62 Movemvf cash HEALTH IS —Robin Kay, president of the 20 Tenant’s payment to I Samuel antimony 13 Northwest 67 A type of rock containing THE MARKET, AND 21 Frozen water 48 Body of water 72 Driving Under the Influence 14 Geologic time minerals om Fashion Design Council of THE THING THAT C 22 Asset deposited to ensure 50 Color of ink indicating a 74 A county in Kentucky or 15 Annual (report) 68 Opposite of she Canada, about LG Fashion IT IS NOT THE repayment deficit the surname of well-known 18 Social Insurance Number 71 The tax on items MAKES YOU FEEL Is BULL SIDE OR THE 24 Not applicable 51 Hernando ____ Soto American militia activist. -

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING in CANADA Thursday, June 1, 2006 Volume 14, Number 2 Page One of Three

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING IN CANADA Thursday, June 1, 2006 Volume 14, Number 2 Page One of Three DO NOT RETRANSMIT THIS ADIO: MOJO Sports Radio (CHMJ) Vancouver, owned by Corus, PUBLICATION BEYOND YOUR will see 14 people out of a job come this weekend. On Monday, June RECEPTION POINT R5, CHMJ begins airing continuous traffic reports during the day and the best of talk from sister station CKNW Vancouver at other times. Howard Christensen, Publisher Broadcast Dialogue New ID is AM730 Continuous Drive Time Traffic and the Best of Talk and 18 Turtle Path will also feature the Vancouver Whitecaps and Giants and Seattle Lagoon City ON L0K 1B0 Seahawks games. Among those out of work are CKNW Sports Director JP (705) 484-0752 [email protected] McConnell and MOJO personalities John McKeachie, Bob Marjanovich, www.broadcastdialogue.com Jeff Paterson and Blake Price. Seen as the 100% CANADIAN As dagger to MOJO’s heart Canada’s public was CHUM-owned Team 1040 Vancouver’s acquisition of broadcaster, CBC offers all Canadians Vancouver Canucks radio rights, owned for decades by broadcasting services CKNW. And earlier, Team 1040 took play-by-play rights to that reflect and celebrate our country’s diverse the BC Lions away from Corus... Y101 (CKBY-FM) Ottawa heritage, culture and stories. is in the midst of a three-day Radiothon – May 31 to June 2 SENIOR BROADCAST TECHNOLOGIST – for the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO). th This is the 8 annual Y101 Country Cares Challenge for Your primary role will be to ensure the CHEO and organizers say they expect to break the $1- maintenance of broadcasting equipment and million dollar mark at this year’s event.. -

Planning for Age-Friendly Cities: Towards a New Model

Planning For Age-Friendly Cities: Towards a New Model by John A. Colangeli A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Planning Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2010 John A. Colangeli 2010 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. John Angelo Colangeli ii Abstract This dissertation examines the potential for professional/community planning to respond pro- actively and strategically to the impending demographic changes which will be brought about by the aging of the baby boom generation. This multi-phased investigation was designed to explore whether professional planning could uncover models and concepts which can be used to make cities and communities more age-friendly. Several conclusions can be drawn from the study. It was found that planners are not ready for demographic change nor are they prepared for helping create age-friendly cities. This is due to several reasons, including a lack of resources forcing them to concentrate on short-term, immediate issues; lack of power and credibility; and a perception that the elderly are a lower priority in society. For planners to become proactive and strategic in planning for age-friendly cities, they will need to re-examine their tendency to focus mainly on land use planning; focus on the long-term agenda; establish credibility with politicians; develop visionary skills; and become educators and facilitators, engaging key stakeholders and community groups. -

Press Release Contains "Forward-Looking Statements"

Tuesday, August 18, 2020 ZoomerMedia Limited Announces Close of Sale of Assets of Darwin CX Inc. (Toronto, Canada – August 18, 2020) Further to its media release dated May 18, 2020, ZoomerMedia Limited (“ZoomerMedia”) (TSXV: ZUM) is pleased to announce that it has closed the agreement (“Purchase Agreement”) for the sale of substantially all of the assets (“Darwin Assets”) of ZoomerMedia’s wholly-owned subsidiary Darwin CX Inc. (“Darwin”), ZoomerMedia’s proprietary subscription and membership management platform, to New York–based Irish Studio LLC (“Irish Studio”). The purchase price was $7,465,000 (CAD), consisting of $700,000 (CAD) received concurrently on signing of the Purchase Agreement, and $5,386,000 (CAD) in cash and a $1,280,000 promissory note of Irish Studio, subject to customary post-closing adjustments, which were received by ZoomerMedia on the closing date. “ZoomerMedia committed significant resources to creating Darwin in a space that hasn’t seen innovation in decades, so it’s not surprising that it developed into a competitive software platform in a short period of time. Darwin naturally complements Irish Studio's core business and they are better positioned to invest the additional resources necessary for long-term growth. The sale price is in line with our expectations, fetches good value for ZML shareholders, strengthens ZML's financial position, and allows us to focus our energy on growing our core media businesses focused on Canada’s 45plus demographic,” said ZoomerMedia Founder and CEO Moses Znaimer. The Special Relationship between ZoomerMedia and Darwin will not end with the sale. ZoomerMedia Chief Digital Officer and Darwin co-founder Omri Tintpulver will sit on Darwin’s Advisory Board, and the company’s operations will continue to be based at ZoomerMedia’s headquarters in Toronto’s Liberty Village for now. -

La Collection Moses Znaimer De Téléviseurs Anciens De La Cinémathèque Québécoise Jean Gagnon

Document generated on 09/29/2021 2:43 a.m. Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies La collection Moses Znaimer de téléviseurs anciens de la Cinémathèque québécoise Jean Gagnon Fictions télévisuelles : approches esthétiques Volume 23, Number 2-3, Spring 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1015191ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1015191ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Cinémas ISSN 1181-6945 (print) 1705-6500 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Gagnon, J. (2013). La collection Moses Znaimer de téléviseurs anciens de la Cinémathèque québécoise. Cinémas, 23(2-3), 201–228. https://doi.org/10.7202/1015191ar Tous droits réservés © Cinémas, 2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ La collection Moses Znaimer de téléviseurs anciens de la Cinémathèque québécoise 1 Jean Gagnon En 2010, la Cinémathèque québécoise (CQ) faisait l’acquisi- tion du meuble projecteur Library Kodascope. Celui-ci com- prend un projecteur Kodascope Model B installé sur une base rotative à 360 degrés surmontant le meuble en marqueterie de noyer de style Art déco faisant à la fois office d’armoire de ran- gement et de piédestal. Le meuble et ses accessoires, issus de la succession du galeriste Gilles Corbeil (1920-1986), avaient été acquis en 1987. -

Notice of Annual General and Special Meeting Management Information Circular

ZOOMERMEDIA LIMITED NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL AND SPECIAL MEETING MANAGEMENT INFORMATION CIRCULAR January7,2020 ZOOMERMEDIA LIMITED NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL AND SPECIAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that an annual general and special meeting of the shareholders of ZoomerMedia Limited (the “Corporation”) will be held at 70 Jefferson Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M6K 1Y4 on Wednesday, February 5, 2020, at the hour of 2:00 pm (Toronto time) for the following purposes: 1. To receive and consider the audited financial statements of the Corporation for the year ended August 31, 2019, together with a report of the auditors thereon; 2. To elect directors; 3. To appoint auditors and to authorize the directors to fix their remuneration; 4. To consider, and if deemed appropriate, to pass with or without variation, an ordinary resolution to approve the Corporation’s stock option plan, as more particularly described in the accompanying information circular; and 5. To transact such further or other business as may properly come before the meeting or any adjournment or adjournments thereof. This notice is accompanied by a form of proxy and management information circular. Shareholders who are unable to attend the meeting in person are requested to complete, date, sign and return the enclosed form of proxy so that as large a representation as possible may be had at the meeting. The audited financial statements of the Corporation for the year ended August 31, 2019 and the associated Management Discussion and Analysis are available on SEDAR. -

Canada’S Communications Magazine

www.broadcastermagazine.com November 2016 $8.00 CANADA’S COMMUNICATIONS MAGAZINE FALL BUYERS’ GUIDE We curate. You create. The Canada Media Fund publishes CMF Trends, a curated source of information that helps you better understand the ongoing changes happening in the world of media and technology. Discover more at CMF-FMC.CA - f in Brought to you by the Government of Canada and Canada's cable, satellite and IPTV distributors. EYE Canada Media Fund C) ON TRENDS CANADA Fonds des medias du Canada Job # CMF_16088 Filename CMF_16088_Broadcaster_Fall Directory_FP_OL.indd Modified 10-27-2016 11:58 AM Created 10-27-2016 11:54 AM Station Micheline Carone Client Contact None Publication(s) Broadcaster Fall Directory CMYK Helvetica Neue LT Std Art Director Mo Ad Number None Production None PUBLICATION Insertion Date None Copy Writer None Bleed 8.375” x 11” INKS INKS PERSONNEL Production Artist Mich Trim 8.125” x 10.75” SETUP Comments full page ad (8.125” x 10.75”) Safety 7” x 10” Editor Lee Rickwood [email protected] Senior Publisher Advertising Sales James A. Cook (416) 510-6871 [email protected] Broadcaster® November 2016 Volume 75 Number 3 Print Production Manager Phyllis Wright (416) 510-6786 Production Manager Alicia Lerma 416-442-5600, Ext 3588 [email protected] Circulation Manager Barbara Adelt 416-442-5600, Ext. 3546 [email protected] Customer Service Bona Lao 416-442-5600, Ext 3552 [email protected] News Service Broadcast News Limited Editorial Deadline Five weeks before publication date. Broadcaster® is published 9 times yearly, by Annex Newcom LP Head Office 80 Valleybrook Drive, 2017 FALL Toronto, Ontario M3B 2S9 Fax: (416) 510-5140 Indexed in Canada Business Index BUYERS’ GUIDE Print edition: ISSN 0008-3038 Online edition: ISSN 1923-340X Iii Miance for . -

I D E Acity Twenty 19

I D E A C I EST. 2000 EST. T Y T W E N T Y 1 9 WORDS FROM MOSES In the fall of ’97, out of the blue, I got a call from Tech was just beginning its crest into the a Richard Saul Wurman, who introduced himself as unstoppable force that it has become, and there an “information architect”, and the organizer of a were many stars both on stage (Herbie Hancock, new kind of conference that he had concocted that I think, or maybe it was Quincy Jones), and in the combined elements of technology, entertainment audience (like Nicholas Negroponte, creator of and design, and that he called “TED”. He said he’d MIT’s Media Lab, and Marvin Minsky, a father of AI), heard about this thing that I had concocted and so you can imagine that I was a bit nervous when installed at the corner of my TV building, some kind I began to talk about little old CityTV and MuchMusic, of Video Booth that sounded like it contained the and how I had put them both on a downtown street, same elements of tech, ent and design, and would visible and interactive in a new kind of wired-up I come down to Monterey to give a 20-minute venerable old building that helped bring the entire Talk about it? area around it back to life. So I did, and found myself in the spring of ’98 at Well, darn if my reel of typical Speakers Corner a small gathering of about 250/300 people, among footage didn’t turn out to be the hit of the conference. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

Nellie’s Annual Report 2018 - 2019 For All Shelter Education Advocacy Women & Children Table of Contents 1 Shelter Stats 2 Shelter Stats 2 Board Chairs’ Report 3 Reasons for coming to Nellie’s Shelter: Programs & Services: Agency Report 4 Abuse 85% 1-on-1 counselling sessions 1470 Homeless 50% Referrals provided 508 Shelter Report 5 Refugee 6% Educational group sessions 18 provided Krystal’s Story 6 Unique Individuals served at the Transportation supports provided 5091 Shelter: Childcare program sessions 208 Donor Profile 7-9 Meals served 39,618 Pre-school (0-3) 22 Shelter spaces provided 141 Thanks to you 10 School Age (4-11) 16 Crisis calls 1285 Youth (12-24) 14 Unique women & children 141 Financial Statement 11 Adults (25-64) 85 staying in the shelter Seniors (64 +) 4 Staff & Volunteer Lists 12-13 Babies born at the Shelter 2 Thank you to our Donors 14-17 Thanks to our Monthly Donors 18 Thank you to our Gift-In-Kind Donors 19 Thank you to our Community Partners 20 Nellie’s Mission Our Mission is to operate programs and services for women and children who have and are experiencing oppressions such as violence, poverty and homelessness. Nellie’s is a community based feminist organization which operates within an anti-racist, anti-oppression framework. We are committed to social change through education and advocacy, to achieve social justice for all women and children. Board Chairs’ Report 3 Agency Report 4 Donna Kellway Sherece Taffe Margarita Mendez Nellie’s is so much more Co-Chair Co-Chair Executive Director than a bed Our job at Nellie’s is to make sure the most Strategic Direction 2: Expand and improve the When a woman arrives at Nellie’s Shelter for the first Because of every single one of our donors, we are vulnerable people in our society don’t go unnoticed. -

ACTRA Dying a Dramatic Death? Canadian Culture

30481 InterACTRA spring 4/2/03 1:11 PM Page 1 Spring 2003 The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists Muzzling Culture What trade agreements have to do with actors PAGE 8 30481 InterACTRA spring 4/2/03 1:11 PM Page 2 Happy Birthday… ACTRA Thor Bishopric CTRA marks its 60th anniversary in But ACTRA can’t do its job fighting on improvements, protecting existing gains, A2003 – celebrating 60 years of great behalf of our members if our resources are while assuring everyone from here to Canadian performances, 60 years con- dwindling. Your decision to strengthen Hollywood that we too want to maintain tributing to and fighting for Canadian ACTRA means we can remain focused stability in our industry. culture and 60 years of advances in pro- and effective in our efforts. The additional And on one final celebratory note, tecting performers. All members should be resources will be directed toward core National Councillor Maria Bircher and very proud of our organization’s tenacity activities such as the fight for Canadian I are beaming with pride over another and grateful to those members who came production, bargaining, and the continued birthday – that of our daughter Teale before us and ensured ACTRA’s success. collection of Use Fees through ACTRA Miranda Bishopric. Teale arrived at In February, ACTRA Toronto kicked PRS. Please see page 6 for more on the St. Mary’s Hospital in Montreal on off our 60th in style by presenting three referendum. February 16th at 10:26 p.m. She was born ACTRA Awards at a reception at the By the time you read this, we will in perfect health. -

The Future Is Female

WINTER 2018 WE SET OUT TO FIND CANADA’S MOST IMPRESSIVE YOUNG PRODUCERS AND DISCOVERED THE FUTURE IS FEMALE PAW PATROL-ING THE WORLD OVER THE TOP? How Spin Master found the right balance We ask Netflix for their of story, product and marketing to create take on the public reaction a global juggernaut to #CreativeCanada 2 LETTER FROM THE CEO TABLE OF 3 LETTER FROM THE CMPA ADDRESSING HARASSMENT WITHIN CONTENTS CANADA’S PRODUCTION SECTOR 12 OVER THE TOP? A CONVERSATION WITH NETFLIX CANADA’S CORIE WRIGHT 4 18 S’EH WHAT? THE NEXT WAVE A LEXICON OF CANADIANISMS FROM YOUR FAVOURITE SHOWS CHECK OUT SOME OF THE BEST AND BRIGHTEST WE GIVE OF CANADA’S EMERGING CREATOR CLASS 20 DON’T CALL IT A REBOOT MICHAEL HEFFERON, RAINMAKER ENTERTAINMENT 22 TRAILBLAZERS CANADA’S INDIE TWO ALUMNI OF THE CMPA MENTORSHIP PROGRAM RISE HIGHER AND HIGHER 24 IN FINE FORMAT PRODUCERS MARIA ARMSTRONG, BIG COAT MEDIA 28 HOSERS TAKE THE WORLD THE TOOLS MARK MONTEFIORE, NEW METRIC MEDIA THEY NEED PRODUCTION LISTS so they can bring 6 30 DRAMA SERIES 44 COMEDY SERIES THE FUTURE IS FEMALE diverse stories to 55 CHILDREN’S AND YOUTH SERIES MEET NINE OF CANADA’S BARRIER-TOPPLING, STEREOTYPE-SMASHING, UP-AND-COMING PRODUCERS 71 DOCUMENTARY SERIES life on screen for 84 UNSCRIPTED SERIES 95 FOREIGN LOCATION SERIES audiences at home and around the world 14 WINTER 2018 THE CMPA A FEW GOOD PUPS HOW SPIN MASTER ENTERTAINMENT ADVOCATES with government on behalf of the industry TURNED PAW PATROL INTO AN PRESIDENT AND CEO: Reynolds Mastin NEGOTIATES with unions and guilds, broadcasters and funders UNSTOPPABLE SUPERBRAND OPENS doors to international markets CREATES professional development opportunities EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Andrew Addison CONTRIBUTING EDITOR: Kyle O’Byrne SECURES exclusive rates for industry events and conferences 26 CONTRIBUTOR AND COPY EDITOR: Lisa Svadjian THAT OLD EDITORIAL ASSISTANT: Kathleen McGouran FAMILIAR FEELING CONTRIBUTING WRITER: Martha Chomyn EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN! DESIGN AND LAYOUT: FleishmanHillard HighRoad JOIN US.