On a Colloquium on TVTV1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TVO Annual Report 19-20 English.Pdf

Ontario Educational Communications Authority Office de la télécommunication éducative de l’Ontario Contents 03 Message from the Chair of TVO’s Board of Directors 04 Message from the Acting Chief Operating Officer 06 Rising to the Challenge of COVID-19 10 50 Years of TVO 14 Digital Learning 18 TVOkids 22 Current Affairs 26 Documentaries 29 Podcasts 31 TVO in Ontario Communities 34 Sound Financial Stewardship 38 Performance and Financial Summary 41 Donor Thank You 43 Leadership Team TVO 2 Annual Report 2019-2020 Message from the Chair of TVO’s Board of Directors I hope this finds you and your loved ones healthy and well. COVID-19 hit hard – here at home and around the world. It brought tragic losses of life and None of this would be possible without the generous support of the Ontario government, TVO livelihoods. It also forced major changes to daily routines. employees and volunteers, our board and regional advisors, our sponsors, and the tens of thousands of individual donors who share Team TVO’s vision of a world made better through As the pandemic spread around the world, Team TVO stepped up in unprecedented ways. Our the power of learning. Thank you all. daily current affairs programs ensured viewers kept well informed about the virus and its impacts. Our educational programming and digital platforms helped learners of all ages, wherever they As you read the following pages, I hope you will reflect not only on the year that was, but also on were, stay engaged and on track. TVO’s potential to inform, inspire, and enlighten for generations to come. -

Liste Des Finalistes En Télévision

Liste des finalistes en télévision MONTRÉAL | TORONTO, 19 janvier 2016 Best Dramatic Series Sponsor | Innovate By Day 19-2 Bravo! (Bell Media) (Sphere Media Plus, Echo Media) Jocelyn Deschenes, Virginia Rankin, Bruce M. Smith, Luc Chatelain, Greg Phillips, Saralo MacGregor, Jesse McKeown Blackstone APTN (Aboriginal Peoples Television Network) (Prairie Dog Film + Television) Ron E. Scott, Jesse Szymanski, Damon Vignale Motive CTV (Bell Media) (Motive Productions III Inc., Lark Productions, Foundation Features) Daniel Cerone, Dennis Heaton, Louise Clark, Rob Merilees, Erin Haskett, Rob LaBelle, Lindsay Macadam, Brad Van Arragon, Kristin Lehman, Sarah Dodd Saving Hope CTV (Bell Media) (Entertainment One, ICF Films) Ilana Frank, David Wellington, Adam Pettle, Morwyn Brebner, John Morayniss, Margaret O'Brien, Lesley Harrison X Company CBC (CBC) (Temple Street Productions) Ivan Schneeberg, David Fortier, Andrea Boyd, Mark Ellis, Stephanie Morgenstern, Bill Haber, Denis McGrath, Rosalie Carew, John Calvert Best Comedy Series Mr. D CBC/City (CBC / Rogers Media) (Mr. D S4 Productions Ltd., Mr. D S4 Ontario Productions Ltd.) Michael Volpe, Gerry Dee PRIX ÉCRANS CANADIENS 2016 | Liste des finalistes en télévision | 1 Mohawk Girls APTN (APTN) (Rezolution Pictures Inc.) Catherine Bainbridge, Christina Fon, Linda Ludwick, Ernest Webb, Tracey Deer, Cynthia Knight Schitt's Creek CBC (CBC) (Not A Real Company Productions Inc.) Eugene Levy, Daniel Levy, Andrew Barnsley, Fred Levy, Ben Feigin, Mike Short, Kevin White, Colin Brunton Tiny Plastic Men Super -

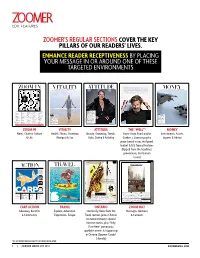

Enhance Reader Receptiveness by Placing Your Message in Or Around One of These Targeted Environments ZOOMER's REGULAR SECTIONS

edit feaTURES ZOOMER’S REGULAR SECTIONS COVER THE KEY PILLARS OF OUR READERS’ LIVES. ENHANCE READER RECEPTIVENESS BY PLACING YOUR MESSAGE IN OR AROUND ONE OF THESE TARGETED ENVIRONMENTS AS AN ACTOR, I’VE REALLY GONE ABOUT NEWS CHATTER CULTURE LIFE EDITOR KIM IZZO BEAUTy grooming trends sTyle EDITor kim ZZOI TRYING TO AS MUCH AS I ZOOM IN VITALITYHEALth fitneSs nutrition sex EDITor vivian vASSOS ATTITUDE MIX UP MY ROLES INVESTMENTsMONEY aSSETs experTs advice EDITor peter muggeridge CAN. IT KEEPS IT INTERESTING FOR ME AND ALSO, HOPEFULLY, PLEASANTLY CONFUSES THE AUDIENCE SO THEY CAN LET ME “BECOME DIFFERENT CHARACTERS” —Je Bridges I’m FIERCELY TKTKTK MAINLY ABOUT MONEY NOT ALL, BUT MOST, OF THE CLUES REFER TO TKTKTKTKTK PROTECTIVE OF ACROSS 40 For each 64 Universal Time 7 Nickel, the element 50 Russian monetary unit EVERY INCH OF THIS 1 European currency 41 US postal code 65 Entice 8 Money 53 Office of 4 Original sum invested 42 Tall rounded vase 66 “On the other hand” in text 9 List deductions on tax EconomicOpportunity THING AND CREATING 12 The root of all evil 43 Greek speak return 55 Profit 16 Gain in value 44 A tax paid in Canada 69 Suffix for forming verbs 10 Of money 57 Chimp SOMETHING THAT HAS ____ THERE IS 17 America 45 Each 70 Each 11 Entice 58 Writer Cummings SEX AND SIZZLE” ONLY ONE SIDE OF 19 Anguish 46 Ancestor of Saul according 71 Symbol for the chemical 12 Time for repayment 62 Movemvf cash HEALTH IS —Robin Kay, president of the 20 Tenant’s payment to I Samuel antimony 13 Northwest 67 A type of rock containing THE MARKET, AND 21 Frozen water 48 Body of water 72 Driving Under the Influence 14 Geologic time minerals om Fashion Design Council of THE THING THAT C 22 Asset deposited to ensure 50 Color of ink indicating a 74 A county in Kentucky or 15 Annual (report) 68 Opposite of she Canada, about LG Fashion IT IS NOT THE repayment deficit the surname of well-known 18 Social Insurance Number 71 The tax on items MAKES YOU FEEL Is BULL SIDE OR THE 24 Not applicable 51 Hernando ____ Soto American militia activist. -

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING in CANADA Thursday, June 1, 2006 Volume 14, Number 2 Page One of Three

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING IN CANADA Thursday, June 1, 2006 Volume 14, Number 2 Page One of Three DO NOT RETRANSMIT THIS ADIO: MOJO Sports Radio (CHMJ) Vancouver, owned by Corus, PUBLICATION BEYOND YOUR will see 14 people out of a job come this weekend. On Monday, June RECEPTION POINT R5, CHMJ begins airing continuous traffic reports during the day and the best of talk from sister station CKNW Vancouver at other times. Howard Christensen, Publisher Broadcast Dialogue New ID is AM730 Continuous Drive Time Traffic and the Best of Talk and 18 Turtle Path will also feature the Vancouver Whitecaps and Giants and Seattle Lagoon City ON L0K 1B0 Seahawks games. Among those out of work are CKNW Sports Director JP (705) 484-0752 [email protected] McConnell and MOJO personalities John McKeachie, Bob Marjanovich, www.broadcastdialogue.com Jeff Paterson and Blake Price. Seen as the 100% CANADIAN As dagger to MOJO’s heart Canada’s public was CHUM-owned Team 1040 Vancouver’s acquisition of broadcaster, CBC offers all Canadians Vancouver Canucks radio rights, owned for decades by broadcasting services CKNW. And earlier, Team 1040 took play-by-play rights to that reflect and celebrate our country’s diverse the BC Lions away from Corus... Y101 (CKBY-FM) Ottawa heritage, culture and stories. is in the midst of a three-day Radiothon – May 31 to June 2 SENIOR BROADCAST TECHNOLOGIST – for the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO). th This is the 8 annual Y101 Country Cares Challenge for Your primary role will be to ensure the CHEO and organizers say they expect to break the $1- maintenance of broadcasting equipment and million dollar mark at this year’s event.. -

Planning for Age-Friendly Cities: Towards a New Model

Planning For Age-Friendly Cities: Towards a New Model by John A. Colangeli A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Planning Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2010 John A. Colangeli 2010 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. John Angelo Colangeli ii Abstract This dissertation examines the potential for professional/community planning to respond pro- actively and strategically to the impending demographic changes which will be brought about by the aging of the baby boom generation. This multi-phased investigation was designed to explore whether professional planning could uncover models and concepts which can be used to make cities and communities more age-friendly. Several conclusions can be drawn from the study. It was found that planners are not ready for demographic change nor are they prepared for helping create age-friendly cities. This is due to several reasons, including a lack of resources forcing them to concentrate on short-term, immediate issues; lack of power and credibility; and a perception that the elderly are a lower priority in society. For planners to become proactive and strategic in planning for age-friendly cities, they will need to re-examine their tendency to focus mainly on land use planning; focus on the long-term agenda; establish credibility with politicians; develop visionary skills; and become educators and facilitators, engaging key stakeholders and community groups. -

Lynn Crosbie Fonds (F0691)

York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) Finding Aid - Lynn Crosbie fonds (F0691) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.1 Printed: September 13, 2019 Language of description: English York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) 305 Scott Library, 4700 Keele Street, York University Toronto Ontario Canada M3J 1P3 Telephone: 416-736-5442 Fax: 416-650-8039 Email: [email protected] http://www.library.yorku.ca/ccm/ArchivesSpecialCollections/index.htm https://atom.library.yorku.ca//index.php/lynn-crosbie-fonds Lynn Crosbie fonds Table of contents Summary information .................................................................................................................................... 19 Administrative history / Biographical sketch ................................................................................................ 19 Scope and content ......................................................................................................................................... 20 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................. 20 Notes .............................................................................................................................................................. 20 Access points ................................................................................................................................................. 21 Collection holdings ....................................................................................................................................... -

December 1994 3

It was a disturbing vision of discrimination. I glimpsed more hord reolii with Terry Jordon. Debntedwith the authorsof Clayoquot Lh Dissent. And felt both poin ond pleasure with Patricia Seaman. Books by Canada’s authors are some of the best books avoiloble. They’re the books we love to rend. took for them ot your fovourite bookstore. 2 ,.’ f ! / , : ..’ ’ I , : : .x,..: . :I ;.i VOLUME XX I I I, NUMBER9 Uncommon Sense JohnRalston Saul aims m nun our turbulenttimes inw anotherage of enlightenment Letter5 . .._............ 5 BY JOHN LOWNSBROUGH GraphicTales by Maurice Vellekoop . 48 The Best of I994 Emkrin Cmoda’s editors name this Pooeby year’srap tides by Rhea Tregebov . 5 I FirstMovels byMaureen McCallum Garvie . 53 ‘Tis the Season Children’s Books There are gik possibilitiesgalore for rhe holidaybook-buyer by Diana Brebner . 55 BY RICHARD PERRY Young Adult Books by Pat Barclay. 57 up front Working Up an Appetite by Barbara Carey . 59 The ISPIT culinq temptations- CanLitAcrortic~8 betweencovers! BY CLARA ALBERT by Fred Sharpe . 60 A BackrvadGlance The Pucks Stop Were by Douglas Fetherling . 6 I Roundingup rhisseason’s sports books. Coren at Large hum on-iceheroics m off-speedpirching by Michael Coren . 62 BY ELIZABETH MITCHELL NewRcdcm by GeorgeBowwing and Katherine Gtier. a biographyof Karen Kain. and much more BEGlNRllPdG ON PAGE 19 Short noticesof ficrion and non-fiction PAGE 49 . ......... Books in Canada December 1994 3 ,.,_ C-n_. _ _ -- ._-- . ._. _ n ny-I___..._ I__. .._.:___.____ . .. Donald Harman Akenson’s lacescbook PUBLISHER is Conor(McGill-Queen’s). a biography of Anita Mleanikcwski Conor Cruise O’Brien. -

Press Release Contains "Forward-Looking Statements"

Tuesday, August 18, 2020 ZoomerMedia Limited Announces Close of Sale of Assets of Darwin CX Inc. (Toronto, Canada – August 18, 2020) Further to its media release dated May 18, 2020, ZoomerMedia Limited (“ZoomerMedia”) (TSXV: ZUM) is pleased to announce that it has closed the agreement (“Purchase Agreement”) for the sale of substantially all of the assets (“Darwin Assets”) of ZoomerMedia’s wholly-owned subsidiary Darwin CX Inc. (“Darwin”), ZoomerMedia’s proprietary subscription and membership management platform, to New York–based Irish Studio LLC (“Irish Studio”). The purchase price was $7,465,000 (CAD), consisting of $700,000 (CAD) received concurrently on signing of the Purchase Agreement, and $5,386,000 (CAD) in cash and a $1,280,000 promissory note of Irish Studio, subject to customary post-closing adjustments, which were received by ZoomerMedia on the closing date. “ZoomerMedia committed significant resources to creating Darwin in a space that hasn’t seen innovation in decades, so it’s not surprising that it developed into a competitive software platform in a short period of time. Darwin naturally complements Irish Studio's core business and they are better positioned to invest the additional resources necessary for long-term growth. The sale price is in line with our expectations, fetches good value for ZML shareholders, strengthens ZML's financial position, and allows us to focus our energy on growing our core media businesses focused on Canada’s 45plus demographic,” said ZoomerMedia Founder and CEO Moses Znaimer. The Special Relationship between ZoomerMedia and Darwin will not end with the sale. ZoomerMedia Chief Digital Officer and Darwin co-founder Omri Tintpulver will sit on Darwin’s Advisory Board, and the company’s operations will continue to be based at ZoomerMedia’s headquarters in Toronto’s Liberty Village for now. -

Paperny Films Fonds

Paperny Films fonds Compiled by Melanie Hardbattle and Christopher Hives (2007) Revised by Emma Wendel (2009) Last revised May 2011 University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Administrative History o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Paperny Film Inc. series o David Paperny series o A Canadian in Korea: A Memoir series o A Flag for Canada series o B.C. Times series o Call Me Average series o Celluloid Dreams series o Chasing the Cure series o Crash Test Mommy (Season I) series o Every Body series o Fallen Hero: The Tommy Prince Story series o Forced March to Freedom series o Indie Truth series o Mordecai: The Life and Times of Mordecai Richler series o Murder in Normandy series o On the Edge: The Life and Times of Nancy Greene series o On Wings and Dreams series o Prairie Fire: The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 series o Singles series o Spring series o Star Spangled Canadians series o The Boys of Buchenwald series o The Dealmaker: The Life and Times of Jimmy Pattison series o The Life and Times of Henry Morgentaler series o Titans series o To Love, Honour and Obey series o To Russia with Fries series o Transplant Tourism series o Victory 1945 series o Brewery Creek series o Burn Baby Burn series o Crash Test Mommy, Season II-III series o Glutton for Punishment, Season I series o Kink, Season I-V series o Life and Times: The Making of Ivan Reitman series o My Fabulous Gay Wedding (First Comes Love), Season I series o New Classics, Season II-V series o Prisoner 88 series o Road Hockey Rumble, Season I series o The Blonde Mystique series o The Broadcast Tapes of Dr. -

La Collection Moses Znaimer De Téléviseurs Anciens De La Cinémathèque Québécoise Jean Gagnon

Document generated on 09/29/2021 2:43 a.m. Cinémas Revue d'études cinématographiques Journal of Film Studies La collection Moses Znaimer de téléviseurs anciens de la Cinémathèque québécoise Jean Gagnon Fictions télévisuelles : approches esthétiques Volume 23, Number 2-3, Spring 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1015191ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1015191ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Cinémas ISSN 1181-6945 (print) 1705-6500 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Gagnon, J. (2013). La collection Moses Znaimer de téléviseurs anciens de la Cinémathèque québécoise. Cinémas, 23(2-3), 201–228. https://doi.org/10.7202/1015191ar Tous droits réservés © Cinémas, 2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ La collection Moses Znaimer de téléviseurs anciens de la Cinémathèque québécoise 1 Jean Gagnon En 2010, la Cinémathèque québécoise (CQ) faisait l’acquisi- tion du meuble projecteur Library Kodascope. Celui-ci com- prend un projecteur Kodascope Model B installé sur une base rotative à 360 degrés surmontant le meuble en marqueterie de noyer de style Art déco faisant à la fois office d’armoire de ran- gement et de piédestal. Le meuble et ses accessoires, issus de la succession du galeriste Gilles Corbeil (1920-1986), avaient été acquis en 1987. -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

Choosing Among Beliefs and Reasoning About Choices Integrative Thinking Through the Prism of Theories of Rational Choice And

Moldoveanu and Martin: Designing the Thinker of the Future page 1 Designing the Thinker of the Future: An Educational Opportunity in Post-Modern High-Capitalism Mihnea Moldoveanu Associate Professor and Director, Marcel Desautels Centre for Integrative Thinking Rotman School of Management University of Toronto Roger Martin Dean and Professor of Strategic Management Rotman School of Management University of Toronto Abstract We argue that contemporary approaches to developing MBA’s face a fundamental challenge arising from (a) a crisis of legitimation of conventional knowledge and authority associated with ‘normal science’-based expertise, (b) a quickly growing dependence of successful managerial action on recognizing and resolving tensions and conflicts among alternative and radically different views of the world and (c) a renewed importance of turning useful knowledge into intelligent action in the face of uncertainty, ambiguity, anomie and moral ambivalence. We describe an approach to managerial skill development based on the recognition of a new and disruptive opportunity in the market for managers: the growing need for the high-value decision maker who successfully manages interactions across multiple, potentially incommensurable conceptual, epistemological and behavioral domains. We propose to address this opportunity via the integrative development of cognitive-behavioral modules that are both useful and important to successful management in post-modern high capitalism and that can be developed from the resource base of existing MBA faculty and on the background of existing communities of practice in business academia. 2 1. Post-Modern High Capitalism: The ‘Interactions revolution’, Tacit Skills, the ‘Ingenuity Gap’ and the New Educational Opportunity Set. Future-looking analyses of the MBA face the difficult task of attempting to do what markets for MBA-educated managerial talent do not easily do.