The JOURNAL of the RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

Displaced Narratives of Iranian Migrants and Refugees: Constructions of Self and the Struggle for Representation

Displaced Narratives of Iranian migrants and Refugees: Constructions of Self and the Struggle for Representation. Submitted by Mammad Aidani Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree for Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, Education and Human Development School of Psychology at the Victoria University, December 2007 1 “I Mammad Aidani declare that the PhD thesis entitled Displaced Narrative of Iranian migrants and refugees: Construction of Self and the Struggle for Representation is no more than 100,000 words in length including quotes and exclusive of tables, figures, appendices, bibliography, references and footnotes. This thesis contains no material that has been submitted previously, in whole or in part , for the award of any other academic degree or diploma. Except where otherwise indicated, this thesis is my won work”. Signature Date 2 Abstract This thesis discusses the multiple narratives of Iranian migrants and refugees living in Melbourne, Australia. The narratives are constructed by men and women who left Iran immediately after the 1979 revolution; the Iran – Iraq war; and Iranians who are recent arrivals in Australia. The narratives of the participants are particularly influenced and contextualized by the 1979 revolution, the 1980-1988 Iran – Iraq War and the post 9/11 political framework. It is within these historical contexts, I argue that Iranian experiences of displacement need to be interpreted. These historical periods not only provide the context for the narratives of the participants but it also gives meaning to how they reconstruct their identities and the emotions of their displacement. This thesis also argues that Iranian migrant and refugee narratives are part of a holistic story that is united rather than separated from one another. -

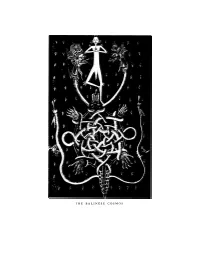

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

Walter Spies, Tourist Art and Balinese Art in Jnter-War .Colonial Bali

Walter Spies, tourist art and Balinese art in inter-war colonial Bali GREEN, Geff <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2482-5256> Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9167/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9167/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. i_caniuiy anu11 services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB 101 708 537 4 Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10697024 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10697024 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. -

The Land of Glory and Beauties

IRAN The Land of Glory and Beauties Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization www.tourismiran.ir Iran is the land of four seasons, history and culture, souvenir and authenticity. This is not a tourism slogan, this is the reality inferred from the experience of visitors who have been impressed by Iran’s beauties and amazing attractions. Antiquity and richness of its culture and civilization, the variety of natural and geographical attractions, four - season climate, diverse cultural sites in addition to different tribes with different and fascinating traditions and customs have made Iran as a treasury of tangible and intangible heritage. Different climates can be found simultaneously in Iran. Some cities have summer weather in winter, or have spring or autumn weather; at the same time in summer you might find some regions covered with snow, icicles or experiencing rain and breeze of spring. Iran is the land of history and culture, not only because of its Pasargad and Persepolis, Chogha Zanbil, Naqsh-e Jahan Square, Yazd and Shiraz, Khuzestan and Isfahan, and its tangible heritage inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List; indeed its millennial civilization and thousands historical and archeological monuments and sites demonstrate variety and value of religious and spiritual heritage, rituals, intact traditions of this country as a sign of authenticity and splendor. Today we have inherited the knowledge and science from scientists, scholars and elites such as Hafez, Saadi Shirazi, Omar Khayyam, Ibn Khaldun, Farabi, IRAN The Land of Glory and Beauties Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Ferdowsi and Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi. Iran is the land of souvenirs with a lot of Bazars and traditional markets. -

Autochthonous Aryans? the Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts

Michael Witzel Harvard University Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts. INTRODUCTION §1. Terminology § 2. Texts § 3. Dates §4. Indo-Aryans in the RV §5. Irano-Aryans in the Avesta §6. The Indo-Iranians §7. An ''Aryan'' Race? §8. Immigration §9. Remembrance of immigration §10. Linguistic and cultural acculturation THE AUTOCHTHONOUS ARYAN THEORY § 11. The ''Aryan Invasion'' and the "Out of India" theories LANGUAGE §12. Vedic, Iranian and Indo-European §13. Absence of Indian influences in Indo-Iranian §14. Date of Indo-Aryan innovations §15. Absence of retroflexes in Iranian §16. Absence of 'Indian' words in Iranian §17. Indo-European words in Indo-Iranian; Indo-European archaisms vs. Indian innovations §18. Absence of Indian influence in Mitanni Indo-Aryan Summary: Linguistics CHRONOLOGY §19. Lack of agreement of the autochthonous theory with the historical evidence: dating of kings and teachers ARCHAEOLOGY __________________________________________ Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7-3 (EJVS) 2001(1-115) Autochthonous Aryans? 2 §20. Archaeology and texts §21. RV and the Indus civilization: horses and chariots §22. Absence of towns in the RV §23. Absence of wheat and rice in the RV §24. RV class society and the Indus civilization §25. The Sarasvatī and dating of the RV and the Bråhmaas §26. Harappan fire rituals? §27. Cultural continuity: pottery and the Indus script VEDIC TEXTS AND SCIENCE §28. The ''astronomical code of the RV'' §29. Astronomy: the equinoxes in ŚB §30. Astronomy: Jyotia Vedåga and the -

Craft Horizons JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1969 $2.00 Potteraipiney Wheel S & CERAMIC EQUIPMENT I

craft horizons JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1969 $2.00 PotterAipiney Wheel s & CERAMIC EQUIPMENT i Operating from one of the most modern facilities of its kind, A. D. Alpine, Inc. has specialized for more than a quarter of a century in the design and manufac- ture of gas and electric kilns, pottery wheels, and a complete line of ceramic equipment. Alpine supplies professional potters, schools, and institutions, throughout the entire United States. We manufacture forty-eight different models of high fire gas and electric kilns. In pottery wheels we have designed an electronically controlled model with vari- able speed and constant torque, but we still manufacture the old "KICK WHEEL" too. ûzùzêog awziözbfe Also available free of charge is our book- let "Planning a Ceramic Studio or an In- stitutional Ceramic Arts Department." WRITE TODAY Dept. A 353 CORAL CIRCLE EL SEGUNDO, CALIF. 90245 AREA CODE (213) 322-2430 772-2SS7 772-2558 horizons crafJanuary/February 196t9 Vol. XXIX No. 1 4 The Craftsman's World 6 Letters 7 Our Contributors 8 Books 10 Three Austrians and the New Jersey Turnpike by Israel Horovitz 14 The Plastics of Architecture by William Gordy 18 The Plastics of Sculpture: Materials and Techniques by Nicholas Roukes 20 Freda Koblick by Nell Znamierowski 22 Reflections on the Machine by John Lahr 26 The New Generation of Ceramic Artists by Erik Gronborg 30 25th Ceramic National by Jean Delius 36 Exhibitions 53 Calendar 54 Where to Show The Cover: "Phenomena Phoenix Run," polyester resin window by Paul Jenkins, 84" x 36", in the "PLASTIC as Plastic" show at New York's Museum of Contemporary Crafts (November 22-Januaiy 12). -

Lost Paradise

The Newsletter | No.61 | Autumn 2012 6 | The Study Lost paradise DUTCH ARTIST, WIllEM GERARD HOFKER (1902-1981), Bali has always been popular with European artists; at the beginning was also found painting in pre-war Bali; he too painted lovely barely-dressed Balinese women. His fellow country- of the previous century they were already enjoying the island’s ancient man, Rudolf Bonnet (1895-1978) produced large drawings, mostly character portraits, in a style resembling Jan Toorop. culture, breathtaking nature and friendly population. In 1932, the aristocratic Walter Spies (1895-1942), a German artist who had moved permanently to Bali in 1925, became known for his mystical Belgian, Jean Le Mayeur (1880-1958), made a home for himself in the tropical and exotic representations of Balinese landscapes. It is clear that the European painters were mainly fascinated paradise; he mainly painted near-nude female dancers and was thus known by the young Balinese beauties, who would pose candidly, and normally bare from the waist up. But other facets of as the ‘Paul Gauguin of Bali’. His colourful impressionist paintings and pastels the island were also appreciated for their beauty, and artists were inspired by tropical landscapes, sawas (rice fields), were sold to American tourists for two or three hundred dollars, which was temples, village scenes and dancers. The Western image of Bali was dominated by the idealisation of its women, a substantial amount at that time. These days, his works are sold for small landscape and exotic nature. fortunes through the international auction houses. Arie Smit and Ubud I visited the Neka Art Museum in the village Ubud, Louis Zweers which is a bubbling hub of Balinese art and culture. -

Arts and Handicraft of the Indian

Srtsi anti Handicraft of tfjc Indian INDIAN CRAFTS DEPARTMENT Uniteb States: Snbian ikfjool CARLISLE, PENNSYLVANIA ( I :u;: so ;913P.m. Jnftian grafts ©ppt. tinted f*tatn Indian &ri)ooI (Sarlislr, pa. Partial list of Scalar Stock --------->. Distributors of Baskets, Head work Nava ho Blankets, Silverware, Moccasins, Beads, Buckskin Work, War Bonnets, Ceremonial Trophies, Pottery, etc. In fact, Everything made_hy the Indian j Introductory. pose of perpetuating native Indian arts and crafts among the Indians, and to distribute among appreciative persons throughout the country the work turned out by the students, as a result of the encouragement of their art here at school, as well as to distribute the finest pieces of workman ship to be found on the reservations, which are produced by the old people. The agents pick out and send to us only the finest quality of genuine Indian work, and we sell these goods at strictly cost price. We are notin the mercantile business and do not solicit wholesale orders, but we will aid those inter ested in securing either single pieces or entire collections. The prices for the same quality goods are about one-half those of the regular dealers. We do not sell for profit, but to assist and encourage Indian Art. Navaho blankets are not cheap goods. It requires a lot of valuable material, a great deal of hard labor, a long time, much skill, and infinite patience to make a fine one; and they can only be cheap by comparison. Measured by this standard, they are very cheap, indeed. No Navaho weaver can turn out fine work rapidly, and when the trader, in compliance with the dealer’s demands for more and cheaper blankets, tries to force the price of her work down, he simply forces inferior work on her and does not get good blankets. -

Packaged for Export 21 February 1984 R Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs Whee Lock House 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover NH 08755

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS BEB-24 28892 Top of the World Laguna Beach CA 92651 Packaged For Export 21 February 1984 r Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs Whee lock House 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover NH 08755 Dear Peter In 1597, eighty-seven years after the Spice Islands were discovered by the Portugese, Dutch ships under the command of Cornelius Houtman dropped anchor near the island of Bali. So warm was the welcome from the local ruler, so abundant the hospitality of the local populace, that many of Houtman's crew refused to leave; it took him two years to round up enough crewmen to sail back to Holland. It took almost another three and a half centuries fo. the rest of the world to make good Houtman's discovery. Today, a bare fifty years since the word got out, Bali suffers from an annual tourist invasion so immense, so rapacious, it threatens the island's traditional culture With complete suffocation. Today, tourist arrivals total around 850,000. By 1986 the numbers are expected to. top 750,000. Not lon afterwards, the Balinese will be playing host to almest a million tourists a year. This on an island of only 5,682 square kilometers" (2,095square miles) with a resident populat$on of almost three million. As Houtman and others found out,_ Bali is unique. I the fifteenth century before the first known Western contact, Bali had been the on-aain, off-again vassal of eastern lava's Majapahit empire. By the sixteenth century, however, Majapahit was decaying and finally fell under the advanci.ng scourge of Islam. -

"Well, I'll Be Off Now"

"WELL, I’LL BE OFF NOW" Walter Spies Based on the recollections and letters of the painter, composer and connoisseur of the art of life by Jean-Claude Kuner translation: Anthony Heric Music by Erik Satie Announcement: "WELL, I’LL BE OFF NOW" Walter Spies O-Ton: Daisy Spies He didn’t like it here at all. Announcement: Based on the recollections and letters of the painter, composer and connoisseur of the art of life by Jean-Claude Kuner O-Ton: Daisy Spies The pretentiousness of the time, the whole movie business, it displeased him greatly. Announcement: With Walter Spies, Leo Spies, Hans Jürgen von der Wense, Irene and Eduard Erdmann; Jane Belo, Martha Spies, Heinrich Hauser, as well as texts from the unfinished novel: PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN. Vicki Baum: Yes, by me, by Vicki Baum Vicki Baum: This is going to be an old-fashioned book full of old-fashioned people with strong and very articulate sentiments. We of that generation know that we were a gang of tough rebels, and look with much smiling pity and a dash of contempt at today’s youth with their load of self-pity and their whining for security. Security, indeed! O-Ton: Balinese painter Anak Agung Gede Meregeg: Music John Cage Meregeg – Translator: When Walter Spies died we felt like children who had lost a parent. Vicki Baum: I just scanned through some of the letters Walter wrote me occasionally and came across a line that was his answer to my well thought-out plans for revisiting his island within three years; after such and such work would be done and such and such things attended to, and such and such contracts expired and what more such complex matters had to be taken care of. -

POCKET PROGRAM May 24-27, 2019

BALTICON 53 POCKET PROGRAM May 24-27, 2019 Note: Program listings are current as of Monday, May 20 at 1:00pm. For up-to-date information, please pick up a schedule grid, the daily Rocket Mail, or see our downloadable, interactive schedule at: https://schedule.balticon.org/ LOCATIONS AND HOURS OF OPERATION Locations and Hours of Operation 5TH FLOOR, ATRIUM ENTRANCE: • Volunteer/Information Desk • Accessibility • Registration o Fri 1pm – 10pm o Sat 8:45am – 7pm o Sun 8:45am – 5pm o Mon 10am – 1:30pm 5TH FLOOR, ATRIUM: • Con Suite: Baltimore A o Friday 4pm – Monday 2pm Except from 3am – 6am • Dealers’ Rooms: Baltimore B & Maryland E/F o Fri 2pm – 7pm o Sat 10am – 7pm o Sun 10am – 7pm o Mon 10am – 2pm • Artist Alley & Writers’ Row o Same hours as Dealers, with breaks for participation in panels, workshops, or other events. • Art Show: Maryland A/B o Fri 5pm – 7pm; 8pm – 10pm o Sat 10am – 8pm o Sun 10am – 1pm; 2:15pm – 5pm o Mon 10am – noon • Masquerade Registration o Fri 4pm – 7pm • LARP Registration o Fri 5pm – 9pm o Sat 9am – 10:45am • Autographs: o See schedule BALTICON 53 POCKET PROGRAM 3 LOCATIONS AND HOURS OF OPERATION 5TH FLOOR: • Con Ops: Fells Point (past elevators) o Friday 2pm – Monday 5pm • Sales Table: outside Federal Hill o Fri 2pm – 6:30pm o Sat 10:30am – 7:30pm o Sun 10:30am – 7:30pm o Mon 10:30am – 3pm • Hal Haag Memorial Game Room: Federal Hill o Fri 4pm – 2am o Sat 10am – 2am o Sun 10am – 2am o Mon 10am – 3pm • RPG Salon: Watertable A 6TH FLOOR: • Open Filk: Kent o Fri 11pm – 2am o Sat 11pm – 2am o Sun 10pm – 2am o Mon 3pm – 5pm • Medical: Room 6017 INVITED PARTICIPANTS ONLY: • Program Ops: Fells Point (past elevators) o Fri 1pm – 8pm o Sat 9am – 3pm o Sun 9am – Noon o Other times: Contact Con Ops • Green Room: 12th Floor Presidential Suite o Fri 1pm – 9pm o Sat 9am – 7pm o Sun 9am – 4pm o Mon 9am – Noon Most convention areas will close by 2am each night.