Kriya and Crafts in Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

Ecotourism at Nusa Penida MPA, Bali: a Pilot for Community Based Approaches to Support the Sustainable Marine Resources Management

Ecotourism at Nusa Penida MPA, Bali: A pilot for community based approaches to support the sustainable marine resources management Presented by Johannes Subijanto Coral Triangle Center Coauthors: S.W.H. Djohani and M. Welly Jl. Danau Tamblingan 78, Sanur, Bali, Indonesia International Conference on Climate Change and Coral Reef Conservation, Okinawa Japan, 30 June 2013 Nusa Penida Islands General features Community, Biodiversity, Aesthetics, Culture, Social-economics • Southeast of Bali Island • Nusa Penida Islands: Penida, Lembongan and Ceningan Islands • Klungkung District – 16 administrative villages, 40 traditional villages (mostly Balinese)- 45.000 inhabitants • Fishers, tourism workers, seaweed farmers, farmers, cattle ranchers • Coral reefs (300 species), mola-mola, manta rays, cetaceans, sharks, mangroves (13 species), seagrass (8 species) • Devotion to tradition, rituals and culture, preserving sacred temples: Pura Penataran Ped, Pura Batu Medauh, Pura Giri Putri and Pura Puncak Mundi. Local Balinese Cultural Festival Marine Recreational Operations Table corals Manta ray (Manta birostris) Oceanic Sunfish (Mola mola) Historical Background Historical Background • 2008 - Initiated cooperation TNC/CTC – Klungkung District Government • Ecological surveys – baseline data • 2009 - Working group on Nusa Penida MPA Establishment (local government agencies, traditional community groups, NGO) • Focus Group Discussions – public consultations & awareness • Marine Area reserved for MPA – 20.057 hectares - Klungkung District Decree no. 12 of -

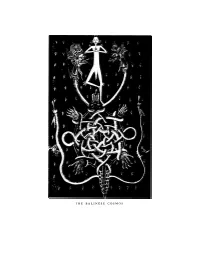

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

The Rise of Private Museums in Indonesia

art in design The Rise of Deborah Iskandar Private Museums Art Consultant — Deborah Iskandar in Indonesia is Principal of ISA Advisory, which advises clients on buying and selling art, and building Until recently, the popular destinations for art lovers in Indonesia had been collections. An expert Yogyakarta, Bandung or Bali. But now things are rapidly changing as private art on Indonesian and international art, she museums are opening in cities all over Indonesia. A good example is Solo, a city in has more than 20 Central Java also known as Surakarta, which boasts an awe-inspiring combination years of experience in Southeast of history and culture. It offers many popular tourist attractions and destinations, Asia, heading including the Keraton Surakarta, and various batik markets. However, despite the both Sotheby’s and Christie’s historical and cultural richness of Solo, it was never really renowned for its art until Indonesia during recently, with luxury hotels increasingly investing in artworks and the opening of her career before 02 establishing ISA Art a new private museum. Advisory in 2013. She is also the Founder arlier this year, Solo finally got its own on those who are genuinely interested in increasing of Indonesian prestigious private museum called their knowledge about art. Luxury, the definitive Tumurun Private Museum. Opened in online resource for April, the Tumurun exhibits contemporary Tumurun prioritises modern and contemporary Indonesian’s looking E to acquire, build and and modern art from both international and local art so that the public, and the younger generation artists and is setting out to educate the people in particular, can learn and understand about style their luxury of Solo about how much art contributes and the evolution of art in Indonesia. -

Character Education Value in the Ngendar Tradition in Piodalan at Penataran Agung Temple

Vol. 2 No. 2 October 2018 Character Education Value in the Ngendar Tradition in Piodalan at Penataran Agung Temple By: Kadek Widiastuti1, Heny Perbowosari2 12Institut Hindu Dharma Negeri Denpasar E-mail : [email protected] Received: August 1, 2018 Accepted: September 2, 2018 Published: October 31, 2018 Abstract The ways to realize the generation which has a character can be apply in the social education through culture values, social ideology and religions, there are in Ngendar’ traditions that was doing by the children’s in Banjar Sekarmukti, Pangsan Village, Petang District, Badung regency. The purpose of this research to analyze the character values from Ngendar tradition. The types of this research are qualitative which ethnographic approach is. These location of this research in Puseh Pungit temple in Penataran Agung areal, Banjar Sekarmukti, Pangsan Village. Researcher using purposive sampling technique to determine information, collecting the data’s using observation, interviews, literature studies and documentation. The descriptive qualitative technique’ that are use to data analyses. The result of this research to show; first is process of Ngendar as heritage that celebrated in six months as an expression about grateful to the God (Ida Sang Hyang Widi Wasa). The reasons why these traditions’ always celebrated by the children’s are affected from holiness, customs and cultures. Second, Ngendar on the naming the characters which is as understanding character children’s with their religion that are affected by two things, the naming about religion behavior with way reprimand and appreciation through their confidence (Sradha) and Karma Phala Sradha. Next function is to grow their awareness. -

Java Batiks to Be Displayed in Indonesian Folk Art Exhibit at International Center

Java batiks to be displayed in Indonesian folk art exhibit at International Center April 22, 1974 Contemporary and traditional batiks from Java will be highlighted in an exhibit of Indonesian folk art May 3 through 5 at the International Center on the Matthews campus of the University of California, San Diego. Some 50 wood carvings from Bali and a variety of contemporary and antique folk art from other islands in the area will also be displayed. Approximately 200 items will be included in the show and sale which is sponsored by Gallery 8, the craft shop in the center. The exhibit will open at 7:30 p.m. Friday, May 3, and will continue from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday, May 4, and Sunday, May 5. Included in the batik collection will be several framed examples completed in the folk tradition of central Java by a noted batik artist, Aziz. Several contemporary paintings from artists' workshop in Java, large contemporary silk panels and traditional patterns made into pillows will also be shown. Wood pieces in the show include unique examples of ritualistic and religious items made in Bali. One of the most outstanding is a 75-year-old winged lion called a singa which is used to ward off evil spirits. The two-foot- high carved figure has a polychrome and gold-leaf finish. Among other items displayed will be carved wooden bells and animals from Bali, ancestral wood carvings from Nias island, leather puppets, food baskets and brass carriage lanterns from Java and implements for making batiks. -

Why Is Yogyakarta the Center of Arts in Indonesia?

art in design Why is Yogyakarta the center of arts in Deborah Indonesia? Iskandar Art Consultant — In this Art in Design section of Indonesia Design, Deborah Iskandar shares her knowledge and love for art. Regarded as a pioneer in the auction world in South East Asia, she knows how to navigate the current evolving market trends of S. Sudjojono, Affandi, and Hendra Gunawan Why is yogyakarta the Art World. the Center of arts in are some of Indonesia’s leading painters indonesia? CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE After more than 20 years’ who founded and participated in the early — experience collectively, Ark Gallery associations of Indonesian art. Persagi, initiated — within the art world, Cemeti Gallery she founded her own by Sudjojono in Jakarta was followed by — advisory firm, ISA Art LEKRA , in Yogjakarta, Both of these societies Alun-Alun Kidul by Jim Allen Abel (Jimbo) Advisory® in 2013. Being were concentrating on art for people and widely respected in OPPOSITE PAGE Indonesia and Singapore supporting the revolution and the founding of — ISA Art Advisory®, aims the Republic of Indonesia. These associations Semar Petruk by Yuswantoro Adi to aid buyers, sellers and went on to become the seeds of the modern art collectors to approach the art world with ease and to establishment that contributed so significantly build collections that will to Indonesia’s modern art identity. retain value over time. In January 1950, ASRI (Akademi Seni ISA Art Advisory® Rupa Indonesia/ Indonesian Academy of Fine Jl. Wijaya Timur Raya No. Art) – now known as Institute Seni Indonesia/ 12 Indonesian Institute of The Art was formed Jakarta 12170 Indonesia through a government initiative to support t. -

Tenaga Dalam Volume 2 - August 1999

Tenaga Dalam Volume 2 - August 1999 The Voice of the Indonesian Pencak Silat Governing Board - USA Branch Welcome to the August issue of Tenaga Dalam. A lot has occurred since May issue. Pendekar Sanders had a very successful seminar in Ireland with Guru Liam McDonald on May 15-16, a very large and successful seminar at Guru Besar Jeff Davidson’s school on June 5-6 and he just returned from a seminar in England. The seminar at Guru Besar Jeff Davidson’s was video taped and the 2 volume set can be purchased through Raja Naga. Tape 1 consists of blakok (crane) training and Tape 2 has about 15 minutes more of blakok training followed by a very intense training session in various animal possessions including the very rare Raja Naga possession. Guru Besar Davidson and his students should be commended on their excellent portrayal of the art. Tape 1 is available to the general public, but due to the intense nature of tape 2 you must be a student. It is with great sadness that I must report that Guru William F. Birge passed away. William was a long time personal student of Pendekar Sanders and he will be missed by all of the people that he came into contact with. 1 Tribute to Guru William F. Birge Your Memory Will Live On In Our Hearts. 2 DJAKARTA aeroplane is a lead-coloured line of sand beaten by EX ‘PEARL OF THE EAST’ waves seeping into a land as flat as Holland. The Dutch settlers who came here in 1618 and founded The following is a passage from the wonderful Batavia must have thought it strangely like their book Magic and Mystics of Java by Nina Epton, homeland. -

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jennifer L. Goodlander August 2010 © 2010 Jennifer L. Goodlander. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali by JENNIFER L. GOODLANDER has been approved for the Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by William F. Condee Professor of Theater Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GOODLANDER, JENNIFER L., Ph.D., August 2010, Interdisciplinary Arts Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali (248 pp.) Director of Dissertation: William F. Condee The role of women in Bali must be understood in relationship to tradition, because “tradition” is an important concept for analyzing Balinese culture, social hierarchy, religious expression, and politics. Wayang kulit, or shadow puppetry, is considered an important Balinese tradition because it connects a mythic past to a political present through public, and often religiously significant ritual performance. The dalang, or puppeteer, is the central figure in this performance genre and is revered in Balinese society as a teacher and priest. Until recently, the dalang has always been male, but now women are studying and performing as dalangs. In order to determine what women in these “non-traditional” roles means for gender hierarchy and the status of these arts as “traditional,” I argue that “tradition” must be understood in relation to three different, yet overlapping, fields: the construction of Bali as a “traditional” society, the role of women in Bali as being governed by “tradition,” and the performing arts as both “traditional” and as a conduit for “tradition.” This dissertation is divided into three sections, beginning in chapters two and three, with a general focus on the “tradition” of wayang kulit through an analysis of the objects and practices of performance. -

Improvement of Indonesian Tourism Sectors to Compete in Southeast Asia

Vincent Jonathan Halim 130218117 IMPROVEMENT OF INDONESIAN TOURISM SECTORS TO COMPETE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA Tourism is an activity that directly touches and engages the community, thus bringing various benefits to the local community and its surroundings. Even tourism is said to have an extraordinary breakthrough energy, which is able to make local people experience metamorphosis in various aspects such as environment, social value & knowledge, job opportunities & opportunities. In the last decade, Indonesia's tourism sector has continued to expand and diversify. Not surprisingly, the government hopes that the tourism sector can bring fresh air in the midst of Indonesia's increasingly slumping oil and gas (oil and gas) and non-oil and gas sectors. Meanwhile, last year, the tourism sector was estimated to be able to contribute to foreign exchange of $ 17.6 billion, an increase of 9.3% from $ 16.1 billion in 2018. This is due to the increasing number of foreign tourist arrivals (tourists). The number of foreign tourists to Indonesia nearly doubled in a decade to 15.8 million in 2018 from 6.2 million in 2008. The government needs extra hard work to ensure the contribution of the tourism sector and competitiveness in South East Asia, also to curb the decline in foreign exchange earnings amid the sluggish world economy. The contribution of the tourism sector internationally and nationally shows positive economic prospects. The role of the government in the form of regulations and policies in tourism development efforts in Indonesia's economic development plan, namely the 2015-2019 RPJMN, shows that the government is aware of the great benefits provided by the tourism sector. -

The Perceived Destination Image of Indonesia: an Assessment on Travel Blogs Written by the Industry’S Top Markets

The perceived destination image of Indonesia: an assessment on travel blogs written by the industry’s top markets By Bernadeth Petriana A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Tourism Management Victoria University of Wellington 2017 1 Abstract The tourist gaze theory suggests that tourists are taught by the destination marketing organisation to know how, when, and where to look. However, the birth of travel blogs has challenged this image as they offer the public “unfiltered” information. Travel bloggers have become more powerful in influencing the decision making of potential tourists. This study employs textual and photographic content analysis to investigate the destination image of Indonesia held by the industry’s key markets; Singapore and Australia. 106 blog entries and over 1,500 pictures were content analysed, and the results suggest that overall tourists tended to have positive images of Indonesia. International tourists are still very much concentrated in the traditionally popular places such as Bali and Jakarta. Negative images of Indonesia include inadequate infrastructure, ineffective wildlife protection, and westernisation of Bali. Natural and cultural resources are proven in this thesis to be Indonesia’s top tourism products. Influenced by their cultural backgrounds, Singaporean and Australian bloggers have demonstrated a dissimilar tourist gaze. The current study also analysed the bloggers’ image of Indonesia as opposed to the image projected by the government through the national tourism brand “Wonderful Indonesia”. The results indicate a narrow gap between the two images. Implications for Indonesian tourism practitioners include stronger law enforcement to preserve local culture and natural attractions, and recognising the market’s preference to promote other destinations. -

Walter Spies, Tourist Art and Balinese Art in Jnter-War .Colonial Bali

Walter Spies, tourist art and Balinese art in inter-war colonial Bali GREEN, Geff <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2482-5256> Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9167/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9167/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. i_caniuiy anu11 services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB 101 708 537 4 Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10697024 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10697024 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O.