Word and Image in Miguel Covarrubias's Island of Bali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

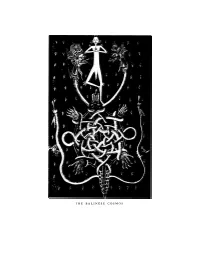

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

Walter Spies, Tourist Art and Balinese Art in Jnter-War .Colonial Bali

Walter Spies, tourist art and Balinese art in inter-war colonial Bali GREEN, Geff <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2482-5256> Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9167/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9167/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. i_caniuiy anu11 services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB 101 708 537 4 Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10697024 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10697024 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. -

Lost Paradise

The Newsletter | No.61 | Autumn 2012 6 | The Study Lost paradise DUTCH ARTIST, WIllEM GERARD HOFKER (1902-1981), Bali has always been popular with European artists; at the beginning was also found painting in pre-war Bali; he too painted lovely barely-dressed Balinese women. His fellow country- of the previous century they were already enjoying the island’s ancient man, Rudolf Bonnet (1895-1978) produced large drawings, mostly character portraits, in a style resembling Jan Toorop. culture, breathtaking nature and friendly population. In 1932, the aristocratic Walter Spies (1895-1942), a German artist who had moved permanently to Bali in 1925, became known for his mystical Belgian, Jean Le Mayeur (1880-1958), made a home for himself in the tropical and exotic representations of Balinese landscapes. It is clear that the European painters were mainly fascinated paradise; he mainly painted near-nude female dancers and was thus known by the young Balinese beauties, who would pose candidly, and normally bare from the waist up. But other facets of as the ‘Paul Gauguin of Bali’. His colourful impressionist paintings and pastels the island were also appreciated for their beauty, and artists were inspired by tropical landscapes, sawas (rice fields), were sold to American tourists for two or three hundred dollars, which was temples, village scenes and dancers. The Western image of Bali was dominated by the idealisation of its women, a substantial amount at that time. These days, his works are sold for small landscape and exotic nature. fortunes through the international auction houses. Arie Smit and Ubud I visited the Neka Art Museum in the village Ubud, Louis Zweers which is a bubbling hub of Balinese art and culture. -

Packaged for Export 21 February 1984 R Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs Whee Lock House 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover NH 08755

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS BEB-24 28892 Top of the World Laguna Beach CA 92651 Packaged For Export 21 February 1984 r Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs Whee lock House 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover NH 08755 Dear Peter In 1597, eighty-seven years after the Spice Islands were discovered by the Portugese, Dutch ships under the command of Cornelius Houtman dropped anchor near the island of Bali. So warm was the welcome from the local ruler, so abundant the hospitality of the local populace, that many of Houtman's crew refused to leave; it took him two years to round up enough crewmen to sail back to Holland. It took almost another three and a half centuries fo. the rest of the world to make good Houtman's discovery. Today, a bare fifty years since the word got out, Bali suffers from an annual tourist invasion so immense, so rapacious, it threatens the island's traditional culture With complete suffocation. Today, tourist arrivals total around 850,000. By 1986 the numbers are expected to. top 750,000. Not lon afterwards, the Balinese will be playing host to almest a million tourists a year. This on an island of only 5,682 square kilometers" (2,095square miles) with a resident populat$on of almost three million. As Houtman and others found out,_ Bali is unique. I the fifteenth century before the first known Western contact, Bali had been the on-aain, off-again vassal of eastern lava's Majapahit empire. By the sixteenth century, however, Majapahit was decaying and finally fell under the advanci.ng scourge of Islam. -

"Well, I'll Be Off Now"

"WELL, I’LL BE OFF NOW" Walter Spies Based on the recollections and letters of the painter, composer and connoisseur of the art of life by Jean-Claude Kuner translation: Anthony Heric Music by Erik Satie Announcement: "WELL, I’LL BE OFF NOW" Walter Spies O-Ton: Daisy Spies He didn’t like it here at all. Announcement: Based on the recollections and letters of the painter, composer and connoisseur of the art of life by Jean-Claude Kuner O-Ton: Daisy Spies The pretentiousness of the time, the whole movie business, it displeased him greatly. Announcement: With Walter Spies, Leo Spies, Hans Jürgen von der Wense, Irene and Eduard Erdmann; Jane Belo, Martha Spies, Heinrich Hauser, as well as texts from the unfinished novel: PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN. Vicki Baum: Yes, by me, by Vicki Baum Vicki Baum: This is going to be an old-fashioned book full of old-fashioned people with strong and very articulate sentiments. We of that generation know that we were a gang of tough rebels, and look with much smiling pity and a dash of contempt at today’s youth with their load of self-pity and their whining for security. Security, indeed! O-Ton: Balinese painter Anak Agung Gede Meregeg: Music John Cage Meregeg – Translator: When Walter Spies died we felt like children who had lost a parent. Vicki Baum: I just scanned through some of the letters Walter wrote me occasionally and came across a line that was his answer to my well thought-out plans for revisiting his island within three years; after such and such work would be done and such and such things attended to, and such and such contracts expired and what more such complex matters had to be taken care of. -

Kriya and Crafts in Indonesia

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 10, 2020: 29-39 Article Received: 13-10-2020 Accepted: 25-10-2020 Available Online: 31-10-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.18533/jah.v9i10.1994 The Cross-conflict of Kriya and Crafts in Indonesia I Ketut Sunarya1 ABSTRACT This article aims to provide information to the wider community about the dichotomy between kriya and crafts. This research uses qualitative research methods with a descriptive type of research. The collated data are information data generated through literature research based on the credibility of naturalistic studies. The results of the research show that the cross-conflict between kriya and crafts makes kriyawan and craftsmen tend to ignore quality. Kriya is the root of visual art in Indonesia. It appears uniquely Indonesian, full of meaning, and in perfect cultivation. The creation of kriya is inseparable from rupabedha as to the characteristics, pramanam as to the perfection of form, sadryam is a creative demand, varnikabhaggam is the certainty of the work’s color, and bawa is the vibration or sincerity. Also, the maker of kriya is kriyawan. In certain areas such as Bali, kriya is a part of life, so it is an adequate and quality art. In Indonesia, kriya has an important position in shaping people’s identity and national culture. It is different from crafts that are closely related to economic needs, a result of diligence, and the product in order to fulfill the tourism industry. Besides, the craft is called pseudo-traditional art or “art in order”, it is an imitation of kriya. -

Pita Maha Social-Institutional Capital

KarenArhamuddin KartomiI T.Wayan Ali. CulturalFirmansah. Ojo Adnyana. Kuwi Survival, RelationFortunaSong Pita Continuanceas CommunistMaha BetweenTyasrinestu. Social Creativity and Discourse Institutional Djohan.theConference Oral and Formation TraditionEconomyEditorial CapitalReport Pita Maha Social-Institutional Capital (A Social Practice on Balinese Painters in 1930s) I Wayan Adnyana Indonesia Institute of the Arts Yogyakarta email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Research Topic: Pita Maha Social-Institutional Capital (A Social Practice on Balinese Painters in 1930s) aims at describing creative waves of Balinese village youth in designing new paintings. The artwork is considered to be the latest development of classical paintings of Kamasan puppet. The pattern of development is not just on artistic technique, but also on aesthetic paradigm. Yet, the invention and development of painting concept, which were previously adopted from stylistic pattern of puppet Kamasan has successfully disseminated paintings as a medium of personal expression. The artist and patron consolidated art practice in the art function, which was well ordered and professional. Agents including palaces, Balinese and foreign painters as well as collectors and dealers were united in arts social movement, named Pita Maha. Despite the fact that Pita Maha also encompassed the sculpture, this research focuses more on the path of paintings. Socio-historical method is applied to explore the characteristics and models of social capital-institutional ideology that brought forth and commercialized paintings on Pita Maha generation. This topic is also an important part of the writer’s dissertation entitled Pita Maha: Social Movement on Balinese Paintings in 1930s. The discussion on social- institutional capital enables expansion and exploration of a more complete socio-historical construction on Pita Maha existence. -

A House in Bali Based on the Memoir by Colin Mcphee (American Premiere)

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Saturday, September 26, 2009, 8pm Sunday, September 27, 2009, 7pm Zellerbach Hall A House in Bali Based on the memoir by Colin McPhee (American Premiere) Bang on a Can All-Stars & Gamelan Salukat Music by Evan Ziporyn Direction by Jay Scheib Choreography by Kadek Dewi Aryani and I Nyoman Catra Libretto by Paul Schick, after Colin McPhee’s A House in Bali and texts by Margaret Mead and Walter Spies Additional dialogue and lyrics by Evan Ziporyn CAST (in order of appearance) Christine Southworth Christine Marc Molomot Colin McPhee Kadek Dewi Aryani Penari, Rantun, Camplung, Lèyak Produced by Bang on a Can in association with Airplane Ears Music. Desak Madé Suarti Laksmi Penari, Ibu, Penyanyi Kekawin I Nyoman Catra Kesyur, Bapak, Kalér, Sagami Producer Kenny Savelson, Bang on a Can Timur Bekbosunov Walter Spies Co-producer & Production Manager Christine Southworth, Airplane Ears Music Anne Harley Margaret Mead Assistant Director & Stage Manager Laine Rettmer Nyoman Triyana Usadhi Sampih Assistant Musical Director Thomas Carr Live Camera AKA ORCHESTRA There will be one 15-minute intermission. Bang on a Can All-Stars Evan Ziporyn, conductor Robert Black, bass; Andrew Cotton, sound engineer; David Cossin, percussion; All music ©2009 Airplane Ears Music (ASCAP). The score toA House in Bali contains references and small quotations Felix Fan, cello; Derek Johnson, guitar; Todd Reynolds, violin; Ning Yu, piano from Colin McPhee’s Kinesis, his Music in Bali trancriptions of Pemungkah (gamelan gender wayang, attributed to I Wayan Lotring) and Sekar Gadung (gamelan gambuh, anonymous). Short fragments of Gamelan Salukat Gong Belaluan’s 1928 Curik Ngaras (transcribed by Evan Ziporyn) and traditional Baris are also referenced. -

For Immediate Release WALTER SPIES to LEAD THE

For Immediate Release 10 April 2003 Contact: Victoria Cheung 852.2978.9919 [email protected] Ruoh-Ling Keong 65.6235 3828 [email protected] WALTER SPIES TO LEAD THE SALE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN AND 20th CENTURY INDIAN PICTURES AT CHRISTIE’S HONG KONG Southeast Asian and 20th Century Indian Pictures 6 July 2003 Walter Spies (Germany 1895-1942) View across the Sawahs to Gunung Agung oil on board, 62 × 91 cm. Estimate: HK$4,500,000-8,000,000 (US$576,900-1,026,000) Hong Kong – The Southeast Asian Pictures sale at Christie’s Hong Kong on 6 July offers an unprecedented selection by the masters of Southeast Asia art as well as a strong selection of 20th Century Indian Pictures. Indo-European Pictures The Indo-European section is exceptionally strong this season featuring works of Walter Spies, Willem Hofker, Miguel Covarrubias, Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur de Merprès and Rudolf Bonnet. The works of Walter Spies (1895-1942), the renowned German artist whose images of Bali have created a vision of the island for posterity, have been breaking auction records for the last three seasons. Christie’s will offer another masterpiece by Spies, View across the Sawahs to Gunung Agung in the spring sale (Estimate: HK$4,500,000-8,000,000/ US$576,900-1,026,000). This work dates from the artist’s much celebrated ‘magic-realist’ period, during which Spies depicts his familiar motifs of Bali - the farmers, the paddy-fields, the animals and the tropical vegetation. In addition, he applied profound perspectives and a clever manipulation of light and shadow that highlights and outlines his subjects to such a dramatic effect, giving a translucent quality as well as spiritual depth to the painting. -

I Gusti Nyoman Lempad

The Newsletter | No.71 | Summer 2015 40 | The Review I Gusti Nyoman Lempad I Gusti Nyoman Lempad is a remarkable figure from the advent of what is now known as Modern Balinese Art. He lived a very long life. He was born in Bedulu in Central Bali around 1862 and he died in 1978 in Ubud, at the astonishing age of 116 years. During his lifetime, Bali changed from a feudal island ruled by 9 kings, to a small part of the Dutch colonial empire, to finally a small province of the Republic of Indonesia. Not only that, from a predominantly rural and agrarian island it changed into what is popularly called a resort, attracting millions of tourists and other visitors each year. Bali was lost to itself; an intricate web of myths, stories and down- right lies increasingly came to change a once vibrant living culture into a living museum, all the while obscuring the real life and needs of a large part of its indigenous population. Although many Balinese reap the fruits of modern developments, it is astonishing that most Balinese, who do not live in paradisiacal conditions – what with poverty, unending traffic jams and horrendous pollution – have not loudly protested against this resort fantasy. Reviewer: Dick van der Meij 1. Reviewed publication: Six international authors on Balinese art have been Carpenter, B.W. et al. 2014. given the opportunity to write short introductory essays Lempad of Bali. The illuminating Line, for the catalogue of Lempad’s work: John Darling, Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, ISBN: 9789814385978 Hedi Hinzler, Kaja McGowan, Soemantri Widagdo, Bruce Carpenter, and Adrian Vickers. -

The JOURNAL of the RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

The JOURNAL OF THE RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES VOLUME XLVIII JUNE 1986 NUMBER I SOME NOTES TOWARD A LIFE OF BERYL DE ZOETE BY MARIAN URY Dr. Ury is a Japan specialist on the comparative literature faculty of the University of California, Davis. She is preparing an expanded biography of de Zoete. BERYL DE ZOETE'S MAJOR WORKS I. Translations Italo Svevo, Confessions ofZeno. 1930. , As a Man Grows Older. 1932. Alberto Moravia, "Agostino." 1947. II. Original books With Walter Spies, Dance and Drama in Bali. 1938. The Other Mind: A Study of Dance in South India, 1953. Dance and Magic Drama in Ceylon, 1957. The Thunder and the Freshness, 1963. 2 THE JOURNAL OF THE The Special Collections of Rutgers University Library possesses a miscellaneous group of books and manuscripts, letters and cards which once belonged to Beryl de Zoete and Arthur Waley and which represent, though not in any systematic way, the activities, interests, tastes and friendships of these two devoted com- panions. Of the pair, it is Arthur Waley who is the better-known; his name is familiar to every student of Chinese and Japanese literature, and to many other educated readers, as that of the scholar whose fine literary sensibility and lyric gifts, supported by his broad and profound learning, gave the Western world translations of East Asian classics free alike of pedantry and amateur exoticism. The full measure of his achievement has yet to be assessed, but it is by any stand- ard a great one. Beryl de Zoete was also a remarkable and, in several respects, distinguished person.