Creating Heritage in Ubud, Bali 251

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

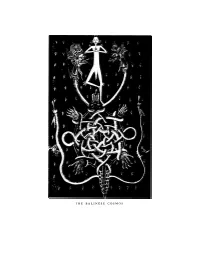

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jennifer L. Goodlander August 2010 © 2010 Jennifer L. Goodlander. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali by JENNIFER L. GOODLANDER has been approved for the Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by William F. Condee Professor of Theater Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GOODLANDER, JENNIFER L., Ph.D., August 2010, Interdisciplinary Arts Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali (248 pp.) Director of Dissertation: William F. Condee The role of women in Bali must be understood in relationship to tradition, because “tradition” is an important concept for analyzing Balinese culture, social hierarchy, religious expression, and politics. Wayang kulit, or shadow puppetry, is considered an important Balinese tradition because it connects a mythic past to a political present through public, and often religiously significant ritual performance. The dalang, or puppeteer, is the central figure in this performance genre and is revered in Balinese society as a teacher and priest. Until recently, the dalang has always been male, but now women are studying and performing as dalangs. In order to determine what women in these “non-traditional” roles means for gender hierarchy and the status of these arts as “traditional,” I argue that “tradition” must be understood in relation to three different, yet overlapping, fields: the construction of Bali as a “traditional” society, the role of women in Bali as being governed by “tradition,” and the performing arts as both “traditional” and as a conduit for “tradition.” This dissertation is divided into three sections, beginning in chapters two and three, with a general focus on the “tradition” of wayang kulit through an analysis of the objects and practices of performance. -

Walter Spies, Tourist Art and Balinese Art in Jnter-War .Colonial Bali

Walter Spies, tourist art and Balinese art in inter-war colonial Bali GREEN, Geff <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2482-5256> Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9167/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9167/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. i_caniuiy anu11 services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB 101 708 537 4 Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10697024 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10697024 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. -

Global Kamasan Siobhan Campbell 1*

Global Kamasan Siobhan Campbell 1* Abstract The painting tradition of Kamasan is often cited as an example of the resilience of traditional Balinese culture in the face of globalisation and the emergence of new forms of art and material culture. This article explores the painting tradition of Kamasan village in East Bali and it’s relationship to the collecting of Balinese art. While Kamasan painting retains important social and religious functions in local culture, the village has a history of interactions between global and local players which has resulted in paintings moving beyond Kamasan to circulate in various locations around Bali and the world. Rather than contribute to the demise of a local religious or cultural practice, exploring the circulation of paintings and the relationship between producers and collectors reveals the nuanced interplay of local and global which characterises the ongoing transformations in traditional cultural practice. Key Words: Kamasan, painting, traditional, contemporary, art, collecting Introduction n 2009 a retrospective was held of works by a major IKamasan artist in two private art galleries in Bali and Java. The Griya Santrian Gallery in Sanur and the Sangkring Art Space in Yogyakarta belong to the realm of contemporary Indonesian art, and the positioning of artist I Nyoman Mandra within this setting revealed the shifting boundaries 1 Siobhan Campbell is a postgraduate research student at the University of Sydney working on a project titled Collecting Balinese Art: the Forge Collection of Balinese Paintings at the Australian Museum. She completed undergraduate studies at the University of New South Wales in Indonesian language and history and is also a qualified Indonesian/English language translator. -

Balinese Cosmology: Study on Pangider Bhuwana Colors in Gianyar’S Contemporary Art

How to Cite Karja, I. W., Ardhana, I. K., & Subrata, I. W. (2020). Balinese cosmology: Study on pangider bhuwana colors in Gianyar’s contemporary art. International Journal of Humanities, Literature & Arts, 3(1), 13-17. https://doi.org/10.31295/ijhla.v3n1.127 Balinese Cosmology: Study on Pangider Bhuwana Colors in Gianyar’s Contemporary Art I Wayan Karja Indonesian Hindu University, Denpasar, Indonesia Corresponding author email: [email protected] I Ketut Ardhana Universitas Hindu Indonesia, Denpasar, Indonesia Email: [email protected] I Wayan Subrata Universitas Hindu Indonesia, Denpasar, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract---Adat (custom) and religion cannot be separated in the context of Balinese culture. One of the aspects of Balinese culture is the concept of mandala, called pangider bhuwana. Based on Balinese culture and religion, the Balinese mandala, is formally known as pangider bhuwana. The main focus of this essay is to explore the way the artist expresses and visualizes, using the colors of the mandala. A comprehensive analysis was conducted on the methods that the colors of the Balinese mandala are visualized in Gianyar's contemporary painting. Keywords---contemporary painting, cosmology, pangider bhuwana colors, visualization. Introduction Balinese cosmology is depicted in mandala form as religious and cosmic symbology, which is used to unify the Self. Based on the Balinese Hindu beliefs and tradition, each direction of the compass embodies specific characteristics (Bandem, 1986; Cameron, 2016; Chopra & Kafatos, 2017; Casas et al., 1991). The most important characteristic is color, while other characteristics include a protective entity, a script, a form of movement, and a balancing force, to name just a few. -

Catalogue 15 X 21 Kebiar Seni XIV MPL

COVER IMAGE I GEDE WIDYANTARA The Ever Changing Face of Bali 115 x 81 cm Acrylic on Canvas FOREWORD Om Swastyastu, It is our pleasure to present our annual exhibition, KebiarSeni XIV, with the theme of REAWAKENING. This year we celebrate the reawakening of the artists in the village of Batuan. In the early 1930s, there was a conuence of ideas between several foreign artists, such as Walter Spies (German)and Rudolf Bonnet (Dutch), and indigenous artisans of Bali that gave birth to the so-called Modern-Traditional Balinese Art. During this time, Bali art community experienced an abrupt shift in subject matter, perspective, composition, coloring techniques and their patron that formed various schools such as Ubud, Sanur and Batuan; each with distinct characteristics. Since then, there have been many inuences coming from various parties and directions. The Batuan artists are now in contact with other Balinese artists, with other artists from dierent regions in Indonesia, with artists in Southeast Asia and with the global artist community. Aligned with the mission of Museum Puri Lukisan to preserve and develop modern- traditional Balinese art, this year we gave the opportunity to the Batuan Artists Association to have their annual exhibition at our museum. A group of younger artists of Batuan innovated a new genre of paintings that signicantly deviate from their tradition, but still maintained their traditional techniques. We hope you enjoy the product of the Reawakening of the younger Batuan Artists, as much as we do. We would like to thank the artists who have participated inthis exhibition, the RatnaWartha Foundation, the entire sta and employees of ourMuseum, Richard Hasell, SoemantriWidagdo,and all those who have helped us to make the annualKebiarSeni exhibition possible. -

Morphological Typology and Origins of the Hindu-Buddhist Candis Which Were Built from 8Th to 17Th Centuries in the Island of Bali

計画系 642 号 【カテゴリーⅠ】 日本建築学会計画系論文集 第74巻 第642号,1857-1866,2009年 8 月 J. Archit. Plann., AIJ, Vol. 74 No. 642, 1857-1866, Aug., 2009 MORPHOLOGICAL TYPOLOGY AND ORIGINS OF THE MORPHOLOGICALHINDU-BUDDHIST TYPOLOGY CANDI ANDARCHITECTURE ORIGINS OF THE HINDU-BUDDHIST CANDI ARCHITECTURE IN BALI ISLAND IN BALI ISLAND バリ島におけるヒンドゥー・仏教チャンディ建築の起源と類型に関する形態学的研究 �������������������������������������� *1 *2 *3 I WayanI Wayan KASTAWAN KASTAWAN * ,¹, Yasuyuki Yasuyuki NAGAFUCHINAGAFUCHI * ² and and Kazuyoshi Kazuyoshi FUMOTO FUMOTO * ³ イ �ワヤン ��� カスタワン ��������,永 渕 康���� 之,麓 �� 和 善 This paper attempts to investigate and analyze the morphological typology and origins of the Hindu-Buddhist candis which were built from 8th to 17th centuries in the island of Bali. Mainly, the discussion will be focused on its characteristics analysis and morphology in order to determine the candi typology in its successive historical period, and the origin will be decided by tracing and comparative study to the other candis that are located across over the island and country as well. As a result, 2 groups which consist of 6 types of `Classical Period` and 1 type as a transition type to `Later Balinese Period`. Then, the Balinese candis can also be categorized into the `Main Type Group` which consists of 3 types, such as Stupa, Prasada, Meru and the `Complementary Type Group` can be divided into 4 types, like Petirthan, Gua, ������ and Gapura. Each type might be divided into 1, 2 or 3 sub-types within its architectural variations. Finally, it is not only the similarities of their candi characteristics and typology can be found but also there were some influences on the development of candis in the Bali Island that originally came from Central and East Java. -

Lost Paradise

The Newsletter | No.61 | Autumn 2012 6 | The Study Lost paradise DUTCH ARTIST, WIllEM GERARD HOFKER (1902-1981), Bali has always been popular with European artists; at the beginning was also found painting in pre-war Bali; he too painted lovely barely-dressed Balinese women. His fellow country- of the previous century they were already enjoying the island’s ancient man, Rudolf Bonnet (1895-1978) produced large drawings, mostly character portraits, in a style resembling Jan Toorop. culture, breathtaking nature and friendly population. In 1932, the aristocratic Walter Spies (1895-1942), a German artist who had moved permanently to Bali in 1925, became known for his mystical Belgian, Jean Le Mayeur (1880-1958), made a home for himself in the tropical and exotic representations of Balinese landscapes. It is clear that the European painters were mainly fascinated paradise; he mainly painted near-nude female dancers and was thus known by the young Balinese beauties, who would pose candidly, and normally bare from the waist up. But other facets of as the ‘Paul Gauguin of Bali’. His colourful impressionist paintings and pastels the island were also appreciated for their beauty, and artists were inspired by tropical landscapes, sawas (rice fields), were sold to American tourists for two or three hundred dollars, which was temples, village scenes and dancers. The Western image of Bali was dominated by the idealisation of its women, a substantial amount at that time. These days, his works are sold for small landscape and exotic nature. fortunes through the international auction houses. Arie Smit and Ubud I visited the Neka Art Museum in the village Ubud, Louis Zweers which is a bubbling hub of Balinese art and culture. -

Packaged for Export 21 February 1984 R Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs Whee Lock House 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover NH 08755

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS BEB-24 28892 Top of the World Laguna Beach CA 92651 Packaged For Export 21 February 1984 r Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs Whee lock House 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover NH 08755 Dear Peter In 1597, eighty-seven years after the Spice Islands were discovered by the Portugese, Dutch ships under the command of Cornelius Houtman dropped anchor near the island of Bali. So warm was the welcome from the local ruler, so abundant the hospitality of the local populace, that many of Houtman's crew refused to leave; it took him two years to round up enough crewmen to sail back to Holland. It took almost another three and a half centuries fo. the rest of the world to make good Houtman's discovery. Today, a bare fifty years since the word got out, Bali suffers from an annual tourist invasion so immense, so rapacious, it threatens the island's traditional culture With complete suffocation. Today, tourist arrivals total around 850,000. By 1986 the numbers are expected to. top 750,000. Not lon afterwards, the Balinese will be playing host to almest a million tourists a year. This on an island of only 5,682 square kilometers" (2,095square miles) with a resident populat$on of almost three million. As Houtman and others found out,_ Bali is unique. I the fifteenth century before the first known Western contact, Bali had been the on-aain, off-again vassal of eastern lava's Majapahit empire. By the sixteenth century, however, Majapahit was decaying and finally fell under the advanci.ng scourge of Islam. -

"Well, I'll Be Off Now"

"WELL, I’LL BE OFF NOW" Walter Spies Based on the recollections and letters of the painter, composer and connoisseur of the art of life by Jean-Claude Kuner translation: Anthony Heric Music by Erik Satie Announcement: "WELL, I’LL BE OFF NOW" Walter Spies O-Ton: Daisy Spies He didn’t like it here at all. Announcement: Based on the recollections and letters of the painter, composer and connoisseur of the art of life by Jean-Claude Kuner O-Ton: Daisy Spies The pretentiousness of the time, the whole movie business, it displeased him greatly. Announcement: With Walter Spies, Leo Spies, Hans Jürgen von der Wense, Irene and Eduard Erdmann; Jane Belo, Martha Spies, Heinrich Hauser, as well as texts from the unfinished novel: PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN. Vicki Baum: Yes, by me, by Vicki Baum Vicki Baum: This is going to be an old-fashioned book full of old-fashioned people with strong and very articulate sentiments. We of that generation know that we were a gang of tough rebels, and look with much smiling pity and a dash of contempt at today’s youth with their load of self-pity and their whining for security. Security, indeed! O-Ton: Balinese painter Anak Agung Gede Meregeg: Music John Cage Meregeg – Translator: When Walter Spies died we felt like children who had lost a parent. Vicki Baum: I just scanned through some of the letters Walter wrote me occasionally and came across a line that was his answer to my well thought-out plans for revisiting his island within three years; after such and such work would be done and such and such things attended to, and such and such contracts expired and what more such complex matters had to be taken care of. -

Kamasan Painting at the Australian Museum, and Beyond

Kamasan Painting at the Australian Museum, and beyond SIOBHAN CAMPBELL he Australian Museum in Sydney houses one of the world’s Collection obscures the distinctions between ethnographic artefact Tbest collections of Balinese art, known as the Forge and fine art which were keenly felt when the Australian Museum Collection. Although this collection is a unique document of acquired the paintings in 1976. Almost forty years later these Balinese visual art, it remains relatively obscure largely because the paintings continue to offer a novel approach to talking and paintings have remained out of public view since the last major thinking about art which challenges the way traditional art is exhibition of the collection in 1978. conceptualised. Anthony Forge (1929-1991) worked with a community Although the oldest Balinese works in existence date from of traditional artists in the village of Kamasan, East Bali during the 18th century, the traditional art of Bali has roots in the wayang the early 1970s.1 Although by no means the first foreigner to visit (shadow puppet theatre) and in the art of the East Javanese or collect work from Kamasan village, Forge can be credited with Majapahit kingdom.2 However, the category of traditional art in the first comprehensive study of traditional art not overshadowed Bali today encompasses a lot more than this narrative painting by artistic developments taking place in other parts of the island. style. Paradoxically, what is more commonly known as traditional While countless observers during the 20th century saw Kamasan as painting is the art which developed around the villages of Ubud, a tradition on the brink of extinction, Forge sought to investigate Batuan and Sanur in the 1930s.3 The narrative painting associated innovation in traditional art and as such the Forge Collection with Kamasan village is now often referred to as classical or wayang provides specific insights into the ways that artists innovate while painting.