Kamasan Painting at the Australian Museum, and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jennifer L. Goodlander August 2010 © 2010 Jennifer L. Goodlander. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali by JENNIFER L. GOODLANDER has been approved for the Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by William F. Condee Professor of Theater Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GOODLANDER, JENNIFER L., Ph.D., August 2010, Interdisciplinary Arts Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali (248 pp.) Director of Dissertation: William F. Condee The role of women in Bali must be understood in relationship to tradition, because “tradition” is an important concept for analyzing Balinese culture, social hierarchy, religious expression, and politics. Wayang kulit, or shadow puppetry, is considered an important Balinese tradition because it connects a mythic past to a political present through public, and often religiously significant ritual performance. The dalang, or puppeteer, is the central figure in this performance genre and is revered in Balinese society as a teacher and priest. Until recently, the dalang has always been male, but now women are studying and performing as dalangs. In order to determine what women in these “non-traditional” roles means for gender hierarchy and the status of these arts as “traditional,” I argue that “tradition” must be understood in relation to three different, yet overlapping, fields: the construction of Bali as a “traditional” society, the role of women in Bali as being governed by “tradition,” and the performing arts as both “traditional” and as a conduit for “tradition.” This dissertation is divided into three sections, beginning in chapters two and three, with a general focus on the “tradition” of wayang kulit through an analysis of the objects and practices of performance. -

Global Kamasan Siobhan Campbell 1*

Global Kamasan Siobhan Campbell 1* Abstract The painting tradition of Kamasan is often cited as an example of the resilience of traditional Balinese culture in the face of globalisation and the emergence of new forms of art and material culture. This article explores the painting tradition of Kamasan village in East Bali and it’s relationship to the collecting of Balinese art. While Kamasan painting retains important social and religious functions in local culture, the village has a history of interactions between global and local players which has resulted in paintings moving beyond Kamasan to circulate in various locations around Bali and the world. Rather than contribute to the demise of a local religious or cultural practice, exploring the circulation of paintings and the relationship between producers and collectors reveals the nuanced interplay of local and global which characterises the ongoing transformations in traditional cultural practice. Key Words: Kamasan, painting, traditional, contemporary, art, collecting Introduction n 2009 a retrospective was held of works by a major IKamasan artist in two private art galleries in Bali and Java. The Griya Santrian Gallery in Sanur and the Sangkring Art Space in Yogyakarta belong to the realm of contemporary Indonesian art, and the positioning of artist I Nyoman Mandra within this setting revealed the shifting boundaries 1 Siobhan Campbell is a postgraduate research student at the University of Sydney working on a project titled Collecting Balinese Art: the Forge Collection of Balinese Paintings at the Australian Museum. She completed undergraduate studies at the University of New South Wales in Indonesian language and history and is also a qualified Indonesian/English language translator. -

Balinese Cosmology: Study on Pangider Bhuwana Colors in Gianyar’S Contemporary Art

How to Cite Karja, I. W., Ardhana, I. K., & Subrata, I. W. (2020). Balinese cosmology: Study on pangider bhuwana colors in Gianyar’s contemporary art. International Journal of Humanities, Literature & Arts, 3(1), 13-17. https://doi.org/10.31295/ijhla.v3n1.127 Balinese Cosmology: Study on Pangider Bhuwana Colors in Gianyar’s Contemporary Art I Wayan Karja Indonesian Hindu University, Denpasar, Indonesia Corresponding author email: [email protected] I Ketut Ardhana Universitas Hindu Indonesia, Denpasar, Indonesia Email: [email protected] I Wayan Subrata Universitas Hindu Indonesia, Denpasar, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract---Adat (custom) and religion cannot be separated in the context of Balinese culture. One of the aspects of Balinese culture is the concept of mandala, called pangider bhuwana. Based on Balinese culture and religion, the Balinese mandala, is formally known as pangider bhuwana. The main focus of this essay is to explore the way the artist expresses and visualizes, using the colors of the mandala. A comprehensive analysis was conducted on the methods that the colors of the Balinese mandala are visualized in Gianyar's contemporary painting. Keywords---contemporary painting, cosmology, pangider bhuwana colors, visualization. Introduction Balinese cosmology is depicted in mandala form as religious and cosmic symbology, which is used to unify the Self. Based on the Balinese Hindu beliefs and tradition, each direction of the compass embodies specific characteristics (Bandem, 1986; Cameron, 2016; Chopra & Kafatos, 2017; Casas et al., 1991). The most important characteristic is color, while other characteristics include a protective entity, a script, a form of movement, and a balancing force, to name just a few. -

Morphological Typology and Origins of the Hindu-Buddhist Candis Which Were Built from 8Th to 17Th Centuries in the Island of Bali

計画系 642 号 【カテゴリーⅠ】 日本建築学会計画系論文集 第74巻 第642号,1857-1866,2009年 8 月 J. Archit. Plann., AIJ, Vol. 74 No. 642, 1857-1866, Aug., 2009 MORPHOLOGICAL TYPOLOGY AND ORIGINS OF THE MORPHOLOGICALHINDU-BUDDHIST TYPOLOGY CANDI ANDARCHITECTURE ORIGINS OF THE HINDU-BUDDHIST CANDI ARCHITECTURE IN BALI ISLAND IN BALI ISLAND バリ島におけるヒンドゥー・仏教チャンディ建築の起源と類型に関する形態学的研究 �������������������������������������� *1 *2 *3 I WayanI Wayan KASTAWAN KASTAWAN * ,¹, Yasuyuki Yasuyuki NAGAFUCHINAGAFUCHI * ² and and Kazuyoshi Kazuyoshi FUMOTO FUMOTO * ³ イ �ワヤン ��� カスタワン ��������,永 渕 康���� 之,麓 �� 和 善 This paper attempts to investigate and analyze the morphological typology and origins of the Hindu-Buddhist candis which were built from 8th to 17th centuries in the island of Bali. Mainly, the discussion will be focused on its characteristics analysis and morphology in order to determine the candi typology in its successive historical period, and the origin will be decided by tracing and comparative study to the other candis that are located across over the island and country as well. As a result, 2 groups which consist of 6 types of `Classical Period` and 1 type as a transition type to `Later Balinese Period`. Then, the Balinese candis can also be categorized into the `Main Type Group` which consists of 3 types, such as Stupa, Prasada, Meru and the `Complementary Type Group` can be divided into 4 types, like Petirthan, Gua, ������ and Gapura. Each type might be divided into 1, 2 or 3 sub-types within its architectural variations. Finally, it is not only the similarities of their candi characteristics and typology can be found but also there were some influences on the development of candis in the Bali Island that originally came from Central and East Java. -

Lost Paradise

The Newsletter | No.61 | Autumn 2012 6 | The Study Lost paradise DUTCH ARTIST, WIllEM GERARD HOFKER (1902-1981), Bali has always been popular with European artists; at the beginning was also found painting in pre-war Bali; he too painted lovely barely-dressed Balinese women. His fellow country- of the previous century they were already enjoying the island’s ancient man, Rudolf Bonnet (1895-1978) produced large drawings, mostly character portraits, in a style resembling Jan Toorop. culture, breathtaking nature and friendly population. In 1932, the aristocratic Walter Spies (1895-1942), a German artist who had moved permanently to Bali in 1925, became known for his mystical Belgian, Jean Le Mayeur (1880-1958), made a home for himself in the tropical and exotic representations of Balinese landscapes. It is clear that the European painters were mainly fascinated paradise; he mainly painted near-nude female dancers and was thus known by the young Balinese beauties, who would pose candidly, and normally bare from the waist up. But other facets of as the ‘Paul Gauguin of Bali’. His colourful impressionist paintings and pastels the island were also appreciated for their beauty, and artists were inspired by tropical landscapes, sawas (rice fields), were sold to American tourists for two or three hundred dollars, which was temples, village scenes and dancers. The Western image of Bali was dominated by the idealisation of its women, a substantial amount at that time. These days, his works are sold for small landscape and exotic nature. fortunes through the international auction houses. Arie Smit and Ubud I visited the Neka Art Museum in the village Ubud, Louis Zweers which is a bubbling hub of Balinese art and culture. -

Packaged for Export 21 February 1984 R Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs Whee Lock House 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover NH 08755

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS BEB-24 28892 Top of the World Laguna Beach CA 92651 Packaged For Export 21 February 1984 r Peter Bird Martin Institute of Current World Affairs Whee lock House 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover NH 08755 Dear Peter In 1597, eighty-seven years after the Spice Islands were discovered by the Portugese, Dutch ships under the command of Cornelius Houtman dropped anchor near the island of Bali. So warm was the welcome from the local ruler, so abundant the hospitality of the local populace, that many of Houtman's crew refused to leave; it took him two years to round up enough crewmen to sail back to Holland. It took almost another three and a half centuries fo. the rest of the world to make good Houtman's discovery. Today, a bare fifty years since the word got out, Bali suffers from an annual tourist invasion so immense, so rapacious, it threatens the island's traditional culture With complete suffocation. Today, tourist arrivals total around 850,000. By 1986 the numbers are expected to. top 750,000. Not lon afterwards, the Balinese will be playing host to almest a million tourists a year. This on an island of only 5,682 square kilometers" (2,095square miles) with a resident populat$on of almost three million. As Houtman and others found out,_ Bali is unique. I the fifteenth century before the first known Western contact, Bali had been the on-aain, off-again vassal of eastern lava's Majapahit empire. By the sixteenth century, however, Majapahit was decaying and finally fell under the advanci.ng scourge of Islam. -

Balinese Contemporary Art: Between Ethnic Memory and Meta-Questioning

Jean Couteau (Balinese Contemporary Art:...) MUDRAVolume Journal26, Number of Art 3, and December Culture 2011 P 280-285 ISSN 0854-3461 Balinese Contemporary Art: Between Ethnic Memory and Meta-questioning JEAN COUTEAU Professor Sarbone University, France E-mail : [email protected] This article propose a definition of Balinese contemporary art that includes new ethnic art andart brut. On the basis of this definition is proposed a new classification of Balinese contemporary artists. Keywords: Contemporary art, Balinese - ness, and culture memory It is not an easy task do define and delineate Balinese “otherness”, which was to Greensberg a scar, became “contemporary” art, so peculiar is the position of later the foundation of a new recognition, this time Balinese culture in the larger Indonesian framework “contemporary”. This development was born from of Indonesia, and so resilient are indigenous a new reality: as capitalism and modernity dug and values and cultural memory in the field of the arts. penetrated ever deeper into the world’s cultures, the But defining Balinese art of the last 10 years is presence of indigenous elements in the latter’s art nevertheless what I am trying to do here. could not be ignored anymore. The groundbreaking exhibition The Magicians of the Earth, held in An attempt was done in a previous issue of 1989 in Paris took this new reality into account. In this magazine to provide a general definition of the words of its curator, Jean-Hubert Martin, one contemporary. A number of writers and a curator could not have “one hundred percent of exhibitions from the region were asked for an opinion. -

Indonesian Majapahit's Jewellery Design Style for European S / S

Indonesian Majapahit’s Jewellery Design Style For European S / S & F / W 2017 Collections Kumara Sadana Putra, S.Ds.,M.A.1,, Bertha Silvia Suteja, S.E.,M.Si.2 1Fakultas Industri Kreatif, Universitas Surabaya, Raya Kalirungkut, Surabaya 60134 Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] 2Fakultas Bisnis Ekonomika, Universitas Surabaya, Raya Kalirungkut, Surabaya 60134 Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Majapahit is the biggest empire ruled in South East Asia during 13-15th centuries. It lies from Sumatra until New Guinea. Consisting of present day Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, southern Thailand, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines, and East Timor. Mojokerto, Indonesia, a modern city called nowadays, are the capital of Majapahit at that time. And nowadays, there are local people from Batan Krajan, small village in the subdistrict Gedeg, Mojokerto, East Java Province, Indonesia, a village that famous for producing silver jewellery. Exports to Germany, Australia, and parts of Asia. But now with the sluggish European markets and instability of silver price, many artisans became lethargic. Through observations of Majapahit local culture, global jewellery trend decoding, online catalog design research and design development. Authors trying to help SMEs like Agung silver, led by Mr. Purbo, as well as Kumbang silver led by Mr. Sochwan to bring back the business in European market. In every stage of creative process this join product development programme inspired from Majapahit’s cultural influence a long time a gosuch traditional motif came from Majapahit’s artefacts such as Batik’s motif, terracotta, temple. Authors also introduce the technology in design process using 3D printer to the craftmen in their traditional workshop environment, in order to create smart R&D process using techonology application. -

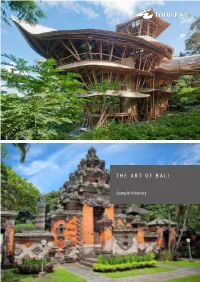

The Art of Bali | Overview

T H E A R T O F B A L I Sample Itinerary THE ART OF BALI | OVERVIEW I TINERARY OVERVIEW 11 Days /10 Nights ART OF BALI FEATURED 6 Nights Ubud EXPERIENCES 5 Nights Seminyak Green Village and Bamboo Factory Ubud Art & Craft Enchanting Ubud Ubud Evening Tour John Hardy Museum Denpasar City Tour Fire and Monkey Dance Learn Balinese Gamelan TO BOOK THIS ITINERARY OR CUSTOMIZE AN ASIA PACIFIC ITINERARY, CONTACT [email protected] OR YOUR LOCAL TOUR EAST SALES REPRESENTATIVE A R T O F B A L I | S A M P L E I T I N E R A R Y ITINERARY DAY 1 Welcome to Bali. Upon arrival at Ngurah Rai Airport, you will be met and transferred to your hotel in Ubud. WELCOME TO BALI! The rest of your day is at leisure to enjoy your hotel and new Bali surroundings. DAY 2 Enjoy the morning at leisure to enjoy the tranquil Ubud village. GREEN VILLAGE AND BAMBOO In the afternoon visit two of Bali’s most green initiatives. Firstly, pay a visit to Bali’s FACTORY Bamboo Factory, a busy hub located on the Agung River where the transformation of bamboo from wild grass to durable building material is showcased. On-site, traditional Balinese craftsmen work alongside a pioneering design firm, IBUKU, to craft sustainable villas, furniture and lots more. On a 1-hour bamboo factory tour, you will be able to see the manufacturing progression from start to finish. You will see how the bamboo is treated and then shaped into all kinds of products including flooring, furniture and doors. -

Wayang Kamasan Painting and Its Development in Bali’S Handicrafts

Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of Culture and Axiology 17(1)/2020: 139-157 Wayang Kamasan Painting and Its Development in Bali’s Handicrafts I Wayan MUDRA Craft Program Study, Faculty of Arts and Design, Indonesian Arts Institute of Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia [email protected] Anak Agung Gede Rai REMAWA Interior Design Study Program, Faculty of Arts and Design, Indonesian Arts Institute of Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia [email protected] I Komang Arba WIRAWAN Television and Film Program Study, Faculty of Arts and Design, Indonesian Arts Institute of Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract: The puppet arts in Bali can be found in the wayang Kamasan painting at Kamasan Village, Klungkung Regency. This painting inspired the creation and de- velopment of new handicraft in Bali. The objectives this research: 1. To find the wayang Kamasan painting in Klungkung Regency; 2. To find the development of handicraft types in Bali inspired by wayang Kamasan painting. This research used a qualitative descriptive approach, and data collection by observation, interview, and documentation. The results that wayang Kamasan painting is estimated to have ex- isted since the reign of the ancient Bali kingdom, which was during the reign of King Dalem Waturenggong in Semarapura Klungkung. The wayang Kamasan paint- ing character painted on a canvas with a light brown base color, stiff, two-dimen- sional, and the description follows the applied standards. The figures depicted taken from Ramayana and Mahabharata story. The Balinese handicrafts inspired by wayang Kamasan painting include ceramics, wovens such as sokasi/keben (basket made of woven bamboo), keris sheath, dulang (trays), bokor (bowls), guitars, beruk (coconut shell containers), and others. -

Balinese Art Versus Global Art1 Adrian Vickers 2

Balinese Art versus Global Art1 Adrian Vickers 2 Abstract There are two reasons why “Balinese art” is not a global art form, first because it became too closely subordinated to tourism between the 1950s and 1970s, and secondly because of confusion about how to classify “modern” and “traditional” Balinese art. The category of ‘modern’ art seems at first to be unproblematic, but looking at Balinese painting from the 1930s to the present day shows that divisions into ‘traditional’, ‘modern’ and ‘contemporary’ are anything but straight-forward. In dismantling the myth that modern Balinese art was a Western creation, this article also shows that Balinese art has a complicated relationship to Indonesian art, and that success as a modern or contemporary artist in Bali depends on going outside the island. Keywords: art, tourism, historiography outheast Asia’s most famous, and most expensive, Spainter is Balinese, but Nyoman Masriadi does not want to be known as a “Balinese artist”. What does this say about the current state of art in Bali, and about Bali’s recognition in global culture? I wish to examine the post-World War II history of Balinese painting based on the view that “modern Balinese” art has lost its way. Examining this hypothesis necessitates looking the alternative path taken by Balinese 1 This paper was presented at Bali World Culture Forum, June 2011, Hotel Bali Beach, Sanur. 2 Adrian Vickers is Professor of Southeast Asian Studies and director of the Australian Centre for Asian Art and Archaeology at the University of Sydney. A version of this paper was given at the Bali World Culture Forum, June 2011. -

Kriya and Crafts in Indonesia

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 10, 2020: 29-39 Article Received: 13-10-2020 Accepted: 25-10-2020 Available Online: 31-10-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.18533/jah.v9i10.1994 The Cross-conflict of Kriya and Crafts in Indonesia I Ketut Sunarya1 ABSTRACT This article aims to provide information to the wider community about the dichotomy between kriya and crafts. This research uses qualitative research methods with a descriptive type of research. The collated data are information data generated through literature research based on the credibility of naturalistic studies. The results of the research show that the cross-conflict between kriya and crafts makes kriyawan and craftsmen tend to ignore quality. Kriya is the root of visual art in Indonesia. It appears uniquely Indonesian, full of meaning, and in perfect cultivation. The creation of kriya is inseparable from rupabedha as to the characteristics, pramanam as to the perfection of form, sadryam is a creative demand, varnikabhaggam is the certainty of the work’s color, and bawa is the vibration or sincerity. Also, the maker of kriya is kriyawan. In certain areas such as Bali, kriya is a part of life, so it is an adequate and quality art. In Indonesia, kriya has an important position in shaping people’s identity and national culture. It is different from crafts that are closely related to economic needs, a result of diligence, and the product in order to fulfill the tourism industry. Besides, the craft is called pseudo-traditional art or “art in order”, it is an imitation of kriya.