John Zachos: Cincinnatian from Constantinople

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LIBRARY of CONGRESS: a DOCUMENTARY HISTORY Guide to the Microfiche Collection

CIS Academic Editions THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS: A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY Guide to the Microfiche Collection Edited by John Y. Cole With a Foreword by Daniel J. Boorstin The Library of Congress The Library of Congress: A Documentary History Guide to the Microfiche Collection Edited by John Y. Cole CIS Academic Editions Congressional Information Service, Inc. Bethesda, Maryland CIS Staff Editor-in-Chief, Special Collections August A. Imholtz, Jr. Staff Assistant Monette Barreiro Vice President, Manufacturing William Smith Director of Communications Richard K. Johnson Designer Alix Stock Production Coordinator Dorothy Rogers Printing Services Manager Lee Mayer Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress The Library of Congress. "CIS academic editions." Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. 1. Library of Congress--History--Sources. 2. Libraries, National--United States--History--Sources. I. Cole, John Young, 1940- . II. Title. III. Series. Z733.U6L45 1987 027.573 87-15580 ISBN 0-88692-122-8 International Standard Book Number: 0-88692-122-8 CIS Academic Editions, Congressional Information Service, Inc. 4520 East-West Highway, Bethesda, Maryland 20814 USA ©1987 by Congressional Information Service, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Contents FOREWORD by Daniel J. Boorstin, Librarian of Congress vii PREFACE by John Y. Cole ix INTRODUCTION: The Library of Congress and Its Multiple Missions by John Y. Cole 1 I. RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF THE LIBRARY Studying the Library of Congress: Resources and Research Opportunities, by John Y. Cole 17 A. Guides to Archival and Manuscript Collections 21 B. General Histories 22 C. Annual Reports 27 D. Early Book Lists and Printed Catalogs (General Collections) 43 E. -

Library of Congress Magazine January/February 2018

INSIDE PLUS A Journey Be Mine, Valentine To Freedom Happy 200th, Mr. Douglass Find Your Roots Voices of Slavery At the Library LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018 Building Black History A New View of Tubman LOC.GOV LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE Library of Congress Magazine Vol. 7 No. 1: January/February 2018 Mission of the Library of Congress The Library’s central mission is to provide Congress, the federal government and the American people with a rich, diverse and enduring source of knowledge that can be relied upon to inform, inspire and engage them, and support their intellectual and creative endeavors. Library of Congress Magazine is issued bimonthly by the Office of Communications of the Library of Congress and distributed free of charge to publicly supported libraries and research institutions, donors, academic libraries, learned societies and allied organizations in the United States. Research institutions and educational organizations in other countries may arrange to receive Library of Congress Magazine on an exchange basis by applying in writing to the Library’s Director for Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-4100. LCM is also available on the web at loc.gov/lcm/. All other correspondence should be addressed to the Office of Communications, Library of Congress, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-1610. [email protected] loc.gov/lcm ISSN 2169-0855 (print) ISSN 2169-0863 (online) Carla D. Hayden Librarian of Congress Gayle Osterberg Executive Editor Mark Hartsell Editor John H. Sayers Managing Editor Ashley Jones Designer Shawn Miller Photo Editor Contributors Bryonna Head Wendi A. -

The Development of Classification at the Library of Congress. Occasional Papers, Number 164

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 247 953 IR 050 836 AUTHOR Miksa, Francis TITLE The Development of Classification at the Library of Congress. Occasional Papers, Number 164. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Graduate School of Library and Information Science. PUB DATE Aug 84 NOTE 81p. AVAILABLE FROMGraduate School of Library and Information Science, Publications Office, University of Illinois, 249 Armory Building, 505 Z. Armory Street, Champaign, IL 61820 ($3.00 per copy; subscription, $13.00 per year). PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from ZDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Classification; History; Indexing; *Library Catalogs; Library Collections IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress Classification; Subject Access (Classification) ABSTRACT This paper traces the development of classification at the Library of Congress in terms of its broader context and by accounting for changes in the present system since its initial period of creation betweeq-1898 and 1910 and the present. Topics covered include: (1) Early Zrowth of thi Collections; (2) Subject Access During the Early Years; (3) A. R. Spofford and the Growth of the Library of Congress; (4) Spofford and Subject Access; (5) From Spofford to John Russell Young; (6) Trends in Classification; (7) A Tentative Beginning, 1897-98; (8) Years of Decision, 1899-1901; (9) Classification Development, 1901 -11: General Features; (10) Classification Development, 1901-11: Collocation Patterns; (11) Progress on the Classification: 1901-11; (12)- Classification Development: 1912-30; (13) Classification Development: 1930-46--An Interlude; and (14) Classification Development: 1947-Present. A Mot of annotated references completes the report. (THC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by ZDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 464 635 IR 058 441 AUTHOR Lamolinara, Guy, Ed. TITLE The Library of Congress Information Bulletin, 2000. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ISSN ISSN-0041-7904 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 480p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/. v PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Library of Congress Information Bulletin; v59 n1-12 2000 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Electronic Libraries; *Exhibits; *Library Collections; *Library Services; *National Libraries; World Wide Web IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress ABSTRACT These 12 issues, representing one calendar year (2000) of "The Library of Congress Information Bulletin," contain information on Library of Congress new collections and program developments, lectures and readings, financial support and materials donations, budget, honors and awards, World Wide Web sites and digital collections, new publications, exhibits, and preservation. Cover stories include:(1) "The Art of Arthur Szyk: 'Artist for Freedom' Featured in Library Exhibition";(2) "The Year in Review: 1999 Marks Start of Bicentennial Celebration"; (3) "'A Whiz of a Wiz': New Library Exhibition on 'The Wizard of Oz' Opens"; (4) "The Many Faces of Thomas Jefferson: Father of the Library Subject of New Exhibition"; (5) Library of Congress bicentennial events; (6) "Thanks for the Memory: New Bob Hope Gallery Opens at Library"; (7) "Local Legacies: American Culture Captured in Bicentennial Program"; (8) "America at Work, School and Play: Web Films Document American Culture, 1894-1915"; (9) "Herblock's History Political Cartoon Exhibition Opens Oct. 17";(10) "Aaron Copland Centennial"; and (11)"Al Hirschfeld: Beyond Broadway: Exhibition of Work by Famed Graphic Artist Open." (Contains 91 references.) MES) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

4016 Congressional Record-House House

4016 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE APRIL 4 EXECUTIVE MESSAGES REFERRED CONFIRMATIONS The PRESIDENT pro tempore laid before the Senate mes Executive nominations confirmed by the Senate April 4 <legis· sages from the President of the United states submitting lative day of March 4), 1940 sundry nominations, which were referred to the appropriate DIPLOMATIC AND FOREIGN SERVICE OF THE UNITED STATES committees. <For nominations this day received, see the end of Senate APPOINTMENTS AND PROMOTIONS proceedings.) To be Foreign Service officers of class 3 EXECUTIVE REPORTS OF COMMITTEES Raymond H. Geist Lester L. Schnare Mr. HARRISON, from the Committee on Finance, reported Loy W. Henderson Samuel H. Wiley favorably the nomination of Martin 0. Bement, of Buffalo, Laurence E. Salisbury N. Y., to be· collector of customs for customs collection To be Foreign Service officers of class 4 district No.9, with headquarters at Buffalo, N.Y. <reappoint Charles A. Bay Samuel Reber ment). Selden Chapin Robert Lacy Smyth Mr. WALSH, from the Committee ori Naval Affairs, reported George F. Kennan Angus I. Ward favorably the nominations of sundry officers for promotion To be Foreign Service officers of class 5 in the Marine Corps. William W. Butterworth, Jr. Gerald Keith Mr. McKELLAR, from the Committee on Post Offices and Paul C. Daniels George H. Winters Post Roads, reported favorably the nominations of several Cecil Wayne Gray postmasters. Mr. BAILEY, from the Committee on Commerce, reported To be Foreign Service officers of class 6 favorably the nomination of Walter George Will, superin Sidney A. Belovsky George M. Graves tendent of lighthouses, to be a commander in the Coast Burton Y. -

THE LIBRARY of CONGRESS's GREAT MANUSCRIPTS ROBBERY, 1896-1897 Nearly Three Million Volumes

THE AMERICAN ARCHIVIST Abstractions of Justice: The Library of Congress's Great Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/62/2/325/2749182/aarc_62_2_34651kg3k10766h0.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 Manuscripts Robbery, 1896-1897 Aaron D. Purcell Abstract In the fall of 1897, the Library of Congress opened the Thomas Jefferson Building and left behind an unfortunate chapter in its history. During the spring of that year two employees were brought to trial and lightly punished for stealing rare materials from the Library, then located in the United States Capitol. Fred Shelley's 1948 American Archivist article discusses this incident, but is incomplete in both content and sources. This essay fully describes the events surrounding the Library of Congress's first major recorded theft of materials and reviews the present status of security at the Library. In the process, this article also discusses general security concerns for modern libraries and archives. ince the opening of the Thomas Jefferson Building in the late 1890s, the Library of Congress has suffered a number of significant thefts from its rich Smanuscript collections. Most recently, during the late 1980s, Charles Merrill Mount attracted national attention with his felonious activities. Throughout the 1990s the Library has reported other significant robberies and reevalu- ated its efforts for preventing such crimes. This apparent outbreak of recent larcenous events and a heightened awareness of the need for better security led the Library to increase protective measures, close its stacks to patrons, and place greater accountability on its staff. Theft of materials from the Library of Congress is not a new phenomenon, however, and the problem can be traced back into the late nineteenth century. -

Class Back to Books School

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 INSIDE The Power of Primary Sources Building Educational Equality PLUS Wagner and Verdi in Their Own Hands Keeping Love of History Alive Social Media Milestones BACK TO CLASS BACK TO BOOKS SCHOOL WWW.LOC.GOV In This Issue SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE FEATURES Library of Congress Magazine Vol. 2 No. 5: September/October 2013 Mission of the Library of Congress If You Build It, They Will Learn 8 Two visionaries worked together 100 years ago to improve education The mission of the Library is to support the for the disadvantaged. Congress in fulfilling its constitutional duties and to further the progress of knowledge and creativity for the benefit of the American people. The Library of Congress in the Classroom 10 Library staff are finding new and exciting ways for teachers and Library of Congress Magazine is issued students across the nation to use the unparalleled resources of the bimonthly by the Office of Communications Library of Congress. of the Library of Congress and distributed free of charge to publicly supported libraries and research institutions, donors, academic libraries, Promoting Science Literacy 22 learned societies and allied organizations in 15 The Library will launch an initiative to build awareness about the Exploring the world the United States. Research institutions and importance of science and promote science education. educational organizations in other countries may arrange to receive Library of Congress Magazine on an exchange basis by applying in writing to the Library’s Director for Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-4100. -

April 2006 (16 Pages)

ISSN: 0047-0414 District of Columbia Library Association Volume 35 Issue 10 April 2006 In April, Think Libraries by Kathryn Ray DCLA, the American Library Association chapter of our nation‘s It’s Spring! There’s no time like April in Washington: National Library capital Week, Legislative Day preparations and, of course, cherry blossoms! ♦ http://www.dcla.org ♦ 202-872-1112 (messages only) National Library Week will be celebrated this year April 2-8. Since 1958, ALA has sponsored National Library Week, a national celebration for Upcoming DCLA libraries and the people who love them. It is a time to honor the contribu- Programs and Meetings tions of our nation’s libraries and librarians and to promote library use and support. National Library Week celebrates all types of libraries – ♦ April 11 (Tues.) 6:00-8:00 school, federal, public, academic, military, law and business and all special DCLA Board Meeting (p. 5) libraries. This year’s theme is "Change your world @ your library®.” For more information about NLW and ALA’s Campaign for America’s Libraries, ♦ April 25 (Tues.) 9:00-4:00 check out http://www.ala.org/ala/pio/campaign/nlw/NLW.htm. Joint Spring Wkshp (p. 4) ♦ May 2 (Tues.) Library Planning is in full swing for Legislative Day. On May 1st and 2nd, hundreds Legislative Day (p. 4) of library supporters from across the country will visit Members of Congress to share stories about libraries in their communities and to talk about ♦ May 4 (Thurs.) 4:00-5:15 library accomplishments and needs. Barbara Folensbee-Moore, DCLA’s DCLA at MLA (p. -

All Members, Past and Present, but in Some Cases the Committee Has Been Unable to Ascertain Anything Definite

The Literary Chili of Cincinnati. 1849. AINSWORTH RAND SPOFFORD. LUCIUS ALONZO HINE. JOHN W. HERRON. HENRY B. BLACKWELL. MEMBERS DURING FIRST CLUB YEAR Now LIVING. THE LITERARY CLUB OF CINCINNATI Constitution, Catalogue if Members, etc. CINCINNATI THE EBBERT & RICHARDSON CO. PUBLISHERS Contents. PAGE Frontispiece, Opposite Title Page Exterior of Club House, Opposite 3 Introductory to Edition of 1903, . 3 Interiors of Club House, . Opposite 5 and 7 Introductory to Edition of 1890, . 5 Extracts from Records, ..... 7 Fiftieth Anniversary of the Club, 11 Constitution, 19 Lists of Officers since February, 1864, 23 Members during First Club Year, 29 Honorary Members, . 30 Active Members, May, 1903, 31 Catalogue of Members, Past and Present, . 33 Papers Read before the Club, . 49 Catalogue of Books and Pamphlets in Club Library Written by Members, etc., . 129 Military Record of Those Who Were or Had Been Members Prior to the Close of the War, . 161 Paintings, Engravings, etc., in the Club Rooms, .169 EXTERIOR VIEW OF CLUB HOUSE. Introductory to Edition of 1903 HE present volume is an enlargement of the volume published T in 1890, revised to date. In preparing it, the Committee has followed the arrangement adopted by its predecessor. Nec essary corrections have been made, where it was practicable to do so, though, owing to the painstaking work of the former com mittee, such changes have been few. There have been added a list of books and pamphlets in the Club library, written by Club mem bers and ex-members; the military record of those in the service of the United States during the Civil War, who were or had been mem bers of the club prior to the close of the war; three pictures of the Club House; and, as a frontispiece, the pictures of those now living who belonged to the Club during the first year of its existence. -

Restructuring the Library of Congress

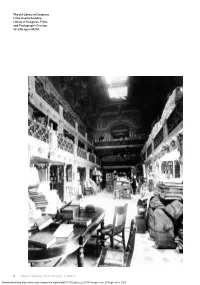

The old Library of Congress in the Capitol building. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-npcc-00203. 6 https://doi.org/10.1162/grey_a_00314 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/grey_a_00314 by guest on 29 September 2021 Stacks, Shelves, and the Law: Restructuring the Library of Congress ZEYNEP ÇELIK ALEXANDER On January 10, 1876, Ainsworth Rand Spofford, the chief librarian of the congressional library located in the Capitol building at the time, complained in a report presented to a United States Congressional Joint Committee that his job had been reduced to “presiding over the greatest chaos in America.”1 By Spofford’s account, the situation in the Library of Congress was dire: This is the fourth year in which the necessity for providing additional room for the rapidly growing stores of this Library has been urged upon the attention of the Congress. During that time 60,000 volumes have been added to the collection. The two wings which were built in 1866, and which absorb all the space within the Capitol which could be annexed to the Library, have been more than filled. The temporary expedients of placing books in double rows upon shelves, and of introducing hundreds of wooden cases of shelving to contain the overflow of the alcoves have been exhausted, and the books are now, from sheer force of necessity, being piled upon the floors in all direction.2 Nor was the problem limited to books: the floor was also littered with maps, pamphlets, newspapers, engravings, and musical scores, among other things. -

Librarians As Wikipedians: from Library History to “Librarianship and Human Rights”

University of South Florida Scholar Commons School of Information Faculty Publications School of Information Summer 2014 Librarians as Wikipedians: From Library History to “Librarianship and Human Rights” Authors: Kathleen de la Peña McCook Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia built collaboratively using wiki software, is the most visited reference site on the web. Only 270 librarians identify as Wikipedians of 21,431,799 Wikipedians with named accounts. This needs to change. Understanding Wikipedia is essential to teaching information literacy and editing Wikipedia is essential to foster successful information-seeking behavior. Librarians who become skilled Wikipedians will maintain the centrality of librarianship to knowledge management in the 21st century—especially through active participation in crowdsourcing. Crowdsourcing is the online participation model that makes use of the collective intelligence of online communities for specific purposes in this case creating and editing articles for Wikipedia. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/si_facpub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation McCook, Kathleen de la Peña, "Librarians as Wikipedians: From Library History to “Librarianship and Human Rights”" (2014). School of Information Faculty Publications. 316. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/si_facpub/316 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Information Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kathleen de la Peña McCook Librarians as Wikipedians From Library History to “Librarianship and Human Rights” Wikipedia: Need for Librarians as Contributors Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia built collaboratively using wiki software, is the most visited reference site on the web.1 Only 270 librarians identify as Wikipedians2 of 21,431,799 Wikipedians with named accounts.3 This needs to change. -

The Almost Magic Pudding

The Almost Magic Pudding: A Brief History and Overview of Australian Materials at the Library of Congress Arthur Emerson, Australia/New Zealand Specialist Humanities and Social Sciences Division, Library of Congress All views and representations expressed in this paper are my own and should not be interpreted as the views or policies of any agency or organization with which I am affiliated. ------------ In searching for a culturally appropriate metaphor to use for the title of this paper, I settled on the Norman Lindsay children's classic The Magic Pudding because it seems to me that the Library of Congress collections have a lot in common with Albert, the titular pudding of Lindsay's tale. Our collections resemble Albert in being substantive, robust, and nourishing (albeit in the intellectual rather than the gastronomic sense). Like Albert, who can morph from steak-and-kidney into various other puddings, our collections are also diverse and somewhat prismatic. Unfortunately, persons using the Library of Congress can occasionally find the experience somewhat trying, rather like encountering Albert in one of his more irascible humors. And while the collections are in a sense self-replenishing (in that they are constantly growing), unlike Albert they are not inexhaustible. Thus, I would characterize our collections as an "almost" magic pudding at best (or perhaps a mundane pudding occasionally manifesting magical traits). My goal for this paper is to provide an overview of the Australian materials in the Library of Congress in the historical context of the Library's growth and development. By way of introduction, I need to address some basic facts about the Library in general, and its Australian materials in particular: 1) The Library of Congress is probably the largest library in the world--but not nearly as big as most people think it is.