Aspect in Spanish Grammar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings. -

A Discourse Analysis of the Periphrastic Imperfect In

A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE PERIPHRASTIC IMPERFECT IN THE GREEK NEW TESTAMENT WRITINGS OF LUKE by CARL E. JOHNSON Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2010 Copyright © by Carl Johnson 2010 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to express my sincere appreciation to each member of my committee whose helpful criticism has made this project possible. I am indebted to Don Burquest for his incredible attention to detail and his invaluable encouragement at certain critical junctures along the way; to my chair Jerold A. Edmondson who challenged me to maintain a linguistic focus and helped me frame this work within the broader linguistic perspective; and to Dr. Chiasson who has helped me write a work that I hope will be accessible to both the linguist and the New Testament Greek scholar. I am also indebted to Robert Longacre who, as an initial member of my committee, provided helpful insight and needed encouragement during the early stages of this work, to Alicia Massingill for graciously proofing numerous editions of this work in a concise and timely manner, and to other members of the Arlington Baptist College family who have provided assistance and encouragement along the way. Finally, I am grateful to my wife, Diana, whose constant love and understanding have made an otherwise impossible task possible. All errors are of course my own, but there would have been far more without the help of many. -

An Introduction to Dena'ina Grammar

AN INTRODUCTION TO DENA’INA GRAMMAR: THE KENAI (OUTER INLET) DIALECT by Alan Boraas, Ph.D. Professor of Anthropology Kenai Peninsula College Based on reference material by: Peter Kalifornsky James Kari, Ph.D. and Joan Tenenbaum, Ph.D. June 30, 2009 revisions May 22, 2010 Page ii Dedication This grammar guide is dedicated to the 20th century children who had their mouth’s washed out with soap or were beaten in the Kenai Territorial School for speaking Dena’ina. And to Peter Kalifornsky, one of those children, who gave his time, knowledge, and friendship so others might learn. Acknowledgement The information in this introductory grammar is based on the sources cited in the “References” section but particularly on James Kari’s draft of Dena’ina Verb Dictionary and Joan Tenenbaum’s 1978 Morphology and Semantics of the Tanaina Verb. Many of the examples are taken directly from these documents but modified to fit the Kenai or Outer Inlet dialect. All of the stem set and verb theme information is from James Kari’s electronic Dena’ina verb dictionary draft. Students should consult the originals for more in-depth descriptions or to resolve difficult constructions. In addition much of the material in this document was initially developed in various language learning documents developed by me, many in collaboration with Peter Kalifornsky or Donita Peter for classes taught at Kenai Peninsula College or the Kenaitze Indian Tribe between 1988 and 2006, and this document represents a recent installment of a progressively more complete grammar. Anyone interested in Dena’ina language and culture owes a huge debt of gratitude to Dr. -

The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect Version 1.0 July 2007 Joshua T. Katz Princeton University Abstract: The origin of the pluperfect is the biggest remaining hole in our understanding of the Ancient Greek verbal system. This paper provides a novel unitary account of all four morphological types— alphathematic, athematic, thematic, and the anomalous Homeric form 3sg. ᾔδη (ēídē) ‘knew’—beginning with a “Jasanoff-type” reconstruction in Proto-Indo-European, an “imperfect of the perfect.” © Joshua T. Katz. [email protected] 2 The following paper has had a long history (see the first footnote). This version, which was composed as such in the first half of 2006, will be appearing in more or less the present form in volume 46 of the Viennese journal Die Sprache. It is dedicated with affection and respect to the great Indo-Europeanist Jay Jasanoff, who turned 65 in June 2007. *** for Jay Jasanoff on his 65th birthday The Oxford English Dictionary defines the rather sad word has-been as “One that has been but is no longer: a person or thing whose career or efficiency belongs to the past, or whose best days are over.” In view of my subject, I may perhaps be allowed to speculate on the meaning of the putative noun *had-been (as in, He’s not just a has-been; he’s a had-been!), surely an even sadder concept, did it but exist. When I first became interested in the Indo- European verb, thanks to Jay Jasanoff’s brilliant teaching, mentoring, and scholarship, the study of pluperfects was not only not a “had-been,” it was almost a blank slate. -

Events in Space

Events in Space Amy Rose Deal University of Massachusetts, Amherst 1. Introduction: space as a verbal category Many languages make use of verbal forms to express spatial relations and distinc- tions. Spatial notions are lexicalized into verb roots, as in come and go; they are expressed by derivational morphology such as Inese˜no Chumash maquti ‘hither and thither’ or Shasta ehee´ ‘downward’ (Mithun 1999: 140-141); and, I will argue, they are expressed by verbal inflectional morphology in Nez Perce. This verbal inflec- tion for space shows a number of parallels with inflection for tense, which it appears immediately below. Like tense, space markers in Nez Perce are a closed-class in- flectional category with a basic locative meaning; they differ in the axis along which their locative meaning is computed. The syntax and semantics of space inflection raises the question of just how tight the liaison is between verbal categories and temporal specification. I argue that in view of the presence of space inflection in languages like Nez Perce, tense marking is best captured as a device for narrowing the temporal coordinates of a spatiotemporally located sentence topic. 2. The grammar of space inflection There are two morphemes in the category of space inflection, cislocative (proximal) -m and translocative (distal) -ki. Space inflection is optional; verbs without space inflection can describe situations that take place anywhere in space.1 I will refer to the members of the space inflection category as space markers. Space inflection is a suffixal category in Nez Perce, and squarely a part of the “inflectional suffix complex” or tense-aspect-mood complex of suffixes. -

A Developmental Perspective on the Imperfective Paradox

Cognition 105 (2007) 65–102 www.elsevier.com/locate/COGNIT A developmental perspective on the Imperfective Paradox Nina Kazanina a,¤, Colin Phillips b a Department of Linguistics, University of Ottawa, 401 Arts Hall, 70 Laurier ave. East, Ottawa, Ont. K1N 6N5, Canada b Department of Linguistics, University of Maryland, 1401 Marie Mount Hall, College Park, MD 20742, USA Received 30 April 2006; revised 23 August 2006; accepted 4 September 2006 Abstract Imperfective or progressive verb morphology makes it possible to use the name of a whole event to refer to an activity that is clearly not a complete instance of that event, leading to what is known as the Imperfective Paradox. For example, a sentence like ‘John was building a house’ does not entail that a house ever got built. The Imperfective Paradox has received a number of diVerent treatments in the philosophical and linguistic literature, but has received less attention from the perspective of language acquisition. This article presents developmental evidence on the nature of the Imperfective Paradox, based on a series of four experiments con- ducted with Russian-speaking 3 to 6 year olds. Despite the fact that Russian is a language in which the morphological form of imperfectives is highly salient and used appropriately at a very young age, younger children show a clearly non-adultlike pattern of comprehension in our experiments. The results from Experiments 1 and 2 suggest that Russian-speaking children incorrectly ascribe completion entailments to imperfectives. However, Experiments 3 and 4 indicate that the children recognize that imperfectives can describe incomplete events, and that their problem instead concerns their inability to Wnd a suitable temporal interval against which to evaluate imperfective statements. -

Tense, Aspect, and Mood in Shekgalagari Thera Crane

UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2009) Tense, Aspect, and Mood in Shekgalagari Thera Crane 1. Introduction and goals Shekgalagari (updated Guthrie number S.31d (Maho 2003) is a Bantu language spoken in western Botswana and parts of eastern Namibia. It is closely related to Setswana, but exhibits a number of phonological, morphological, and tonal phenomena not evident in Setswana. It has been described by Dickens (1986), but its complex Tense, Aspect, and Mood (TAM)-marking system remains largely undescribed. This paper represents an effort to initiate such a description. It is by no means complete, but I hope that it may spur further investigation and description. Data were collected in the spring semester of 2008 at the University of California, Berkeley, in consultation with Dr. Kemmonye “Kems” Monaka, a native speaker and visiting Fulbright Scholar from the University of Botswana. All errors, of course, are my own. Data for this paper were collected as part of a study of Shekgalagari tone and downstep involving Dr. Monaka, Professor Larry Hyman of the University of California, Berkeley, and the author of this paper. Data are drawn from the notes of the author and of Professor Hyman, and from personal communications with Dr. Monaka. Because the aim of the study was not the description of the TAM system as such, a number of forms were not elicited and are missing from this document. All need further investigation in terms of their semantics, pragmatics, and range of uses. Particular areas of interest for future study are noted throughout. 1.1. Structure of paper Section 2 gives a general introduction to tone in Shekgalagari and important tone processes, including phrasal penultimate lengthening and lowering (2.2), spreading rules including grammatical H assignment (with “unbounded spreading”; 2.3) and bounded high-tone spreading (2.4), and downstep (2.5). -

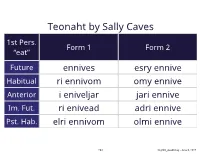

Linguistics 183, Class Slides, Week 3, Day 4

Teonaht by Sally Caves 1st Pers. Form 1 Form 2 “eat” Future ennives esry ennive Habitual ri ennivom omy ennive Anterior i eniveljar jari ennive Im. Fut. ri enivead adri ennive Pst. Hab. elri ennivom olmi ennive 269 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 ASTAPORI VALYRIAN 270 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 5,000 years before the present, the Valyrian Freehold conquered the Ghiscari Empire. High Valyrian replaced Ghiscari as the language of Ghis. 271 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 In Astapor and the other cities, Ghiscari words mixed with High Valyrian grammar and produced a creole that became Astapori Valyrian. 272 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 273 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Ghiscari Astapori Valyrian 274 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 Background High Valyrian Verbs 275 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Subject Agreement with Person and Number 7 Tense/Aspect Combos 2 Modes 2 Voices 276 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Tense/Aspect Present Past Incomplete Anterior (Past/Present) Future Habitual (Past/Present) 277 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Modes Indicative Subjunctive 278 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Voices Active Passive 279 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian Present Singular Plural 1st Pers. vestran vestri 2nd Pers. vestraː vestraːt 3rd Pers. vestras vestris 280 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian 1st Pers. Indicative Subjunctive Present vestran vestron Past Inc. vestrilen vestrilon Ant. Pres. vestretan vestreton 281 ling183_week3.key - June 8, 2017 High Valyrian 1st Pers. Indicative Subjunctive Ant. Past vestreten vestreton Future vestrinna vestrilun Hab. Prs. vestrin vestrun Hab.