A Tale of Two F1 Matras Part Two (Matra MS10)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Independent Club for Slot-Car Enthusiasts There Are More Questions Than Answers Contents

No.230 MAY 2001 The independent club for slot-car enthusiasts BY SUBSCRIPTION ONLY © NSCC 2001 Contents There are more questions than answers Club Stuff.....................................2 Swapmeets...................................3 hy is there only one Monopolies Commission? Diary Dates..................................4 hy is there only one word for Thesaurus? Membership Update....................5 ho did shoot the deputy if Bob Marley didn’t? Members Moments.....................7 W Factory Focus................................8 However, the one that really puzzles me is:- Why don’t people read Day In The Life...........................9 Chevron B19 review...................11 the rules before they send me a members advert for inclusion in the British GT Report......................15 Journal? Every month I reject at least two because of missing Website Survey...........................18 membership numbers or some other misdemeanour. If I am in Letters.........................................19 good humour I return them for amendment; if I am feeling Tyrrell F1 Cars..........................22 grumpy, or there are too many of them, they end up in the round Slot Classic Review.....................25 grey filing cabinet! The other month I received a cracker - a list of Auto Unions ..............................27 cars for sale with no contact details whatsoever. I am still waiting Cup Of Cheer............................29 for someone to complain about its non-appearance so I can be rude Bits And Pieces..........................30 to them. Building Buildings.....................31 The most common reason for rejection concerns email addresses; Rubber Track Part 4..................34 the rules state quite clearly that if an advert contains one then it Interesting Cardboard...............35 must be sent electronically. This is because it makes the job of Carrera Sauber Review..............38 Members Adverts.......................39 compiling the adverts easier; an email I can transfer to the page in thirty seconds whereas hard copy takes considerably longer. -

Mclaren - the CARS

McLAREN - THE CARS Copyright © 2011 Coterie Press Ltd/McLaren Group Ltd McLAREN - THE CARS INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION WILLIAM TAYLOR WILLIAM TAYLOR Bruce Leslie McLaren’s earliest competitive driving While he was learning how to compete at this level, the experiences came at the wheel of a highly modified 1929 Ulster period was of crucial importance to Bruce when it Austin Ulster, an open-topped version of Britain’s cheap came to gaining an understanding of the mechanical side and ubiquitous Austin Seven. Spurred on by his father, of the sport. As a result, by the early 1950s he was already Les, a skilled engineer and a keen motorsports a highly capable and ingenious mechanic, something he enthusiast, Bruce’s initiation into the relatively small ably demonstrated when the Ulster’s cylinder head community of New Zealand and Australian racing drivers eventually cracked. Rescuing a suitable replacement from took place at a hillclimb at Muriwai Beach in 1952. It a humble 1936 Austin Ruby saloon, he filled the combustion was about 25 miles from the McLaren family home in chambers with bronze which he then expertly ground to the Auckland, and happened to be part of their holiday appropriate shape using a rotary file. Once the engine was home. He had just turned 15. reassembled the Ulster proved good for 87mph, a 20 per cent improvement on its official quoted maximum of 72mph. The Ulster had already been in the family for almost three years, having been acquired by Les, in many pieces, for Thereafter such detail improvements came one after another. -

SPR Spark-2015(7.5Mb).Pdf

9 1/43 I~c M;tns Win11er•s IO 1/43 Lc Mans Classic 6 IllS LeMaR~~~~~~~~~~~ 7 Ill s 1!18 Po•·schc Rucin~ & Rond Cau•s 35 1/43 42 1/43 Atltet•icatl & Ettt•OJlCan MG-Pagani Classics Po1•sche 36 l /43 45 1/43 Rn,llye & Hill Climb National rrhemes 4I l /43 47 Otu• Website Met•cedes F1 2015- New collection coming soon • Mercedes F1 WOS No.44 Winner Abu Dhabi GP 2014 Lewis Hamilton 53142 185159 Spark F1 Collection 2014 4 1/18th Le Mans 1/12th Porsche Bentley 3L No,8 Winner Le Mans 1924 J Oulf • F Clement 18LM24 Porsche 90416 No.32 Porsche 356 4th Le Mans 1965 Speedster black Alia Romeo 8C, No,9 H. Unge • P. Nocker 12$002 Winner Le Mans 1934 12$003 Porsche 911K, No.22 P. Etancelin -L. Chinet6 Wilner Le Mans 1971 Aston Martin DBR1 No.5 18LM34 H. Mal1<o • van Lennep Winner Le Mans 1959 G. 18LM71 R. Salvadiru ·C. Shelby 18LM59 1/18th Le Mans Winners Audl R18 E-tron quattro No.2 Audl R18 Tnl, No.1 Audl R18 TOI, No.2 AUOI R 15 +, No.9 A. McNtsh. T. Kristensen • L. Duval B. Treluyer . A.Lotterer . M.Fassler B. Treluyer. A Letterer . M Fassler R. Dumas . M. Rockenfeller • T Bemhard 18LM13 18LM12 18LM11 18LM10 Audl R10 Tnl, No.2 Audl R10 Tnl, No.1 Audl R10 TDI, No.8 Porsche 911 GT1 , No.26 A. McNtsh • R Capello • T. Kristensen F. Biela · E. Ptrro- M. Womer F. -

1990 Primer Gran Premio De México 1990 LA FICHA

1990 Primer Gran Premio de México 1990 LA FICHA GP DE MÉXICO XIV GRAN PREMIO DE MÉXICO Sexta carrera del año 24 de junio de 1990 En el “Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez”. Distrito Federal (carrera # 490 de la historia) Con 69 laps de 4,421 m., para un total de 305.049 Km Podio: 1- A. Prost/ Ferrari 2- N. Mansell/ Ferrari 3- G. Berger/ McLaren Crono del ganador: 1h 32m 35.783s a 197.664 Kph/ prom (Grid: 13º) 9 puntos Vuelta + Rápida: Alain Prost/ Ferrari (la 58ª) de 1m 17.958s a 204.156 Kph/prom Líderes: Ayrton Senna/ McLaren (de la 1 a la 60) y, Alain Prost/ Ferrari (de la 61 a la 69) Pole position: Gerhard Berger/ McLaren-Honda 1m 17.227s a 206.089 Kph/ prom Pista: seca INSCRITOS FONDO # PILOTO NAC EQUIPO MOTOR CIL NEUM P # 1 ALAIN PROST FRA Scuderia Ferrari SpA Ferrari 641 Ferrari 036 V-12 3.5 Goodyear 2 NIGEL MANSELL ING Scuderia Ferrari SpA Ferrari 641 Ferrari 036 V-12 3.5 Goodyear 3 SATORU NAKAJIMA JAP Tyrrell Racing Organisation Tyrrell 019 Ford Cosworth DFR V-8 3.5 Pirelli 4 JEAN ALESI FRA Tyrrell Racing Organisation Tyrrell 019 Ford Cosworth DFR V-8 3.5 Pirelli 5 THIERRY BOUTSEN BÉL Canon Williams Team Williams FW-13B Renault RS2 V-10 3.5 Goodyear 6 RICCARDO PATRESE ITA Canon Williams Team Williams FW-13B Renault RS2 V-10 3.5 Goodyear 7 DAVID BRABHAM AUS Motor Racing Developments Brabham BT-59 Judd EV V-8 3.5 Pirelli 8 STEFANO MODENA ITA Motor Racing Developments Brabham BT-59 Judd EV V-8 3.5 Pirelli 9 MICHELE ALBORETO ITA Footwork Arrows Racing Arrows A-11B Ford Cosworth DFR V-8 3.5 Goodyear 10 ALEX CAFFI ITA Footwork Arrows Racing -

November 2020

The official newsletter of The Revs Institute Volunteers The Revs Institute 2500 S. Horseshoe Drive Naples, Florida, 34104 (239) 687-7387 Editor: Eric Jensen [email protected] Assistant Editor: Morris Cooper Volume 26.3 November 2020 Thanks to this month’s Chairman’s contributors: Chip Halverson Notes Joe Ryan Mark Kregg As I sit here and write this on 11/4, even though we do not have a Susann Miller winner in the Presidential election from yesterday, I am happy to get Mark Koestner one more thing from 2020 off my plate. Only 2 months left to go in 2020, thank goodness. It has been quite a year. Susan Kuehne As always, in anticipation of reopening, Revs Institute has all safety Inside this protocols and guidelines in place, but at present no opening date has November Issue: been released. Many of our volunteers have attended our “Returning with Confidence” training session either in person or online. Volunteer Cruise-In 2 I have received official word from Carl Grant that the museum intends Tappet Trivia 3 to remain closed to the public until the early January, however management will continue to monitor and reevaluate the situation as New Road Trip 4 things progress. Automotive Forum 5 Your Board, with the assistance of Revs Institute staff, are putting Cosworth DFX 6 together some exciting opportunities for volunteers to remain engaged Motorsports 2020 10 while the museum is closed to the public, so be sure to monitor your email for the most up-to-date news. I would like to thank Susan for her Tappet Tech 16 efforts to get us interesting and informative links on a regular basis. -

1 for Its Fifth Participation at Retromobile, Ascott Collection Will

For its fifth participation at Retromobile, Ascott Collection will be presenting a selection of historic racing cars. The Formula 1 car of John Surtees and Mike Hailwood, two world motorsport champions. John Surtees was greatly attached to the SURTESS TS9B # 5, keeping it right up until 1999. This historic F1 car made a name for itself in the streets of Monaco, where it regularly finished among the leaders of the 1966 -1972 editions of the Monaco Grand Prix Historique. The Chevron B16 # 4. No doubt one of the finest prototypes of the 70's. Ascott Collection is proud to have the privilege of offering for sale chassis No. 4, a B16 that is widely known for its authenticity and its history, with participations in the 24 Hours of Daytona and the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1970 to its credit: in short, a car that has now acquired considerable rarity value.... Now that historic races have incorporated a new generation of racing cars, Ascott Collection will be exhibiting a 2009 ORECA FLM09 at the Historic Sportscar Racing stand. The HSR hosts a series of historic races on the other side of the Atlantic, including one of the world's finest historic races, the HSR Classic 24 Hours of Daytona. With Lister having relaunched the production of a new series of only 10 Lister Knobblys, Ascott Collection will be offering for sale N° 7, which is ready to race, in its magnificent livery... The gorgeous 1988 MARCH BUICK 86G MOMO will be presented. Bought, sponsored and extensively raced in 1988 by Gianpiero Moretti, the owner of MOMO, it is the most developed MARCH BUICK 86G from the IMSA GTP period. -

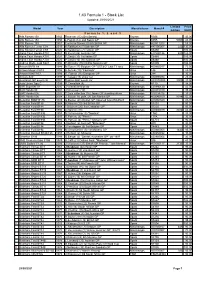

Stock List Updated 28/09/2021

1:43 Formula 1 - Stock List Updated 28/09/2021 Limited Price Model Year Description Manufacturer Manuf # Edition (AUD) F o r m u l a 1 , 2 a n d 3 Alfa Romeo 158 1950 Race car (25) (Oro Series) Brumm R036 35.00 Alfa Romeo 158 1950 L.Fagioli (12) 2nd Swiss GP Brumm S055 5000 40.00 Alfa Romeo 159 1951 Consalvo Sanesi (3) 6th British GP Minichamps 400511203 55.00 Alfa Romeo Ferrari C38 2019 K.Raikkonen (7) Bahrain GP Minichamps 447190007 222 135.00 Alfa Romeo Ferrari C39 2020 K.Raikkonen (7) Turkish GP Spark S6492 100.00 Alpha Tauri Honda AT01 2020 D.Kvyat (26) Austrian GP Minichamps 417200126 400 125.00 Alpha Tauri Honda AT01 2020 P.Gasly (10) 1st Italian GP Spark S6480 105.00 Alpha Tauri Honda AT01 2020 P.Gasly (10) 7th Austrian GP Spark S6468 100.00 Andrea Moda Judd S921 1992 P.McCathy (35) DNPQ Monaco GP Spark S3899 100.00 Arrows BMW A8 1986 M.Surer (17) Belgium GP "USF&G" Last F1 race Minichamps 400860017 75.00 Arrows Mugen FA13 1992 A.Suzuki (10) "Footwork" Onyx 146 25.00 Arrows Hart FA17 1996 R. Rosset (16) European GP Onyx 284 30.00 Arrows A20 1999 T.Takagi (15) show car Minichamps 430990084 25.00 Australian GP Event car 2001 Qantas AGP Event car Minichamps AC4010300 3000 40.00 Auto Union Tipo C 1936 R.Gemellate (6) Brumm R110 38.00 BAR Supertec 01 2000 J.Villeneuve test car Minichamps 430990120 40.00 BAR Honda 03 2001 J.Villeneuve (10) Minichamps 400010010 35.00 BAR Honda 005 2003 T.Sato collection (16) Japan GP standing driver Minichamps 518034316 35.00 BAR Honda 006 2004 J. -

Tyrrell 010/2 Description AB

! 1980 Tyrrell 010 Chassis No: 010/2 • A competitive and useable ground effect entry to the flourishing FIA Historic Formula One Championship, with a sister 010 taking eight wins so far this season. • Historian Allen Brown has confirmed that this car was the replacement 010/2 for Daly at the US GP in 1980. Driven in 1981 by Ricardo Zunino and Eddie Cheever, with a 4th place at the British Grand Prix for Cheever, before being sold by Tyrrell as a complete entity to Roy Lane. • HSCC Historic Formula 1 Champion with Richard Peacock in 1989. • In the current ownership for the last 20 years, with minimal use. The Tyrrell Racing Organisation is a name that rings out with some of the all time Formula 1 greats, with three Formula 1 World Championships and one Constructors Championship to its name. It’s founder, Ken Tyrrell first came into racing in 1958 when he ran three Formula 3 cars for himself and a couple of local stars. Ken soon realised that he was not destined to be a racing driver and stood down from driving duties in 1959, instead to focus on running a Formula Junior team from a woodshed owned by his family business, Tyrrell Brothers. Tyrrell ran a variety of cars in the lower formulas through the 1960s, giving drivers like John Surtees, Jacky Ickx and most notably Jackie Stewart their single seater debuts. In 1968, Tyrrell’s involvement with Matra in Formula 2 was stepped up to the main stage of Formula 1, where Ken ran Matra International, a joint venture between Tyrrell and Matra. -

Hesketh 308, 1975

Hesketh 308, 1975 1975 was the year in which James Hunt won his first Grand Prix, notably holding off Niki Lauda in the Ferrari 312T at Zandvoort, Holland. This was a race, which started in wet conditions, later changing to dry, requiring a change to slicks. It was Hunt who courageously took on slicks earlier than others when he realised there was an advantage to being on dry tyres a lap or two ahead of the opposition. This enabled him to get ahead and win the race. The somewhat outrageous team effort which began in 1973 was now firmly on the map, giving Hunt that vital confidence from his first GP win, in turn resulting in him being signed up for McLaren for 1976, the rest is history as they say. I first wanted to build a 1/12 model of this car when I saw John Shinton’s 1/43 example. I bought a kit to act as a reference and John supplied me with a few photos of the car in a state of renovation and some scale drawings. I built an exact monocoque from plasticard, using the scale drawings. The rollover bar was made from 3mm brass rod, which can be annealed on a gas cooker flame and then shaped more easily. The forward dashboard hoop was similarly made and the essential monocoque was complete. It was absolutely necessary to observe some of the complex angles of the tapering chassis and the inwardly inclined chassis sides towards the region of the footbox. The rollover bars were firmly secured inside the monocoque with epoxy resin. -

Formule 1 1969

1969 Grote prijs van Zuid Afrika Kyalami, 1 maart 1969 Nr. Coureur Auto / motor Startopst. Raceresultaat: 7 Jackie Stewart Matra MS10/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 4 1 met 178.029 km/h 20 Jackie Stewart Matra MS80/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 - Training 8 J.P.Beltoise Matra MS10/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 11 6 Grote prijs van Spanje Montjuich Park, 4 mei 1969 Nr. Coureur Auto / motor Startopst. Raceresultaat: 7 Jackie Stewart Matra MS80/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 4 1 met 149.521 km/h 8 J.P.Beltoise Matra MS80/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 12 3 Grote prijs van Monaco 1969 Nr. Coureur Auto / motor Startopst. Raceresultaat: 7 Jackie Stewart Matra MS80/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 1 Aandrijfas (1) 8 J.P.Beltoise Matra MS80/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 3 Aandrijfas (3) Grote prijs van Nederland 1969 Nr. Coureur Auto / motor Startopst. Raceresultaat: 4 Jackie Stewart Matra MS10/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 2 1 5 J.P.Beltoise Matra MS10/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 11 8 Grote prijs van Frankrijk 1969 Nr. Coureur Auto / motor Startopst. Raceresultaat: 2 Jackie Stewart Matra MS10/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 1 1 7 J.P.Beltoise Matra MS10/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 5 2 Dubbele overwinning !! Grote prijs van England 1969 Nr. Coureur Auto / motor Startopst. Raceresultaat: 3 Jackie Stewart Matra MS80/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 2 1 30 Jackie Stewart Matra MS80/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 - Training 4 J.P.Beltoise Matra MS80/Ford Cosworth DFV 3.0 V8 17 9 Grote prijs van Duitsland 1969 Nr. -

Číslo Modelu

Číslo modelu Model Rok Jazdec Veľká cena Poznámka Vyšiel /nevyšiel 001 Minardi M02 2000 Gené / Mazzacane free, 2003, 9/2009 002 McLaren MP4/15 2000 Hakkinen / Coulthard free, Abc 46/18, 2002 003 Jordan EJ10 2000 Frentzen / Trulli Formule 1 č. 1 004 Arrows A21 2000 de la Rosa / Verstappen 2002, 9/2009 005 Jaguar R1 2000 Irvine / Herbert 2002, Speciál Formule 1 (ABC 11/2003), 9/2009 006 Prost AP03 2000 Alesi / Heidfeld Formule 1 č. 5 007 Benetton B200 2000 Fisichella / Wurz Speciál Formule 1 (ABC 11/2003), 6/2008 008 BAR 002 2000 Villeneuve / Zonta Formule 1 č. 3, 2/2010 009 Williams FW22 2000 Schumacher / Button Speciál Formule 1 (ABC 11/2003) 010 Sauber C19 2000 Salo / Diniz 2002, 9/2009 011 Ferrari F1 2000 2000 Schumacher / Barichello Formule 1 č. 4, 11/2010 012 Lotus 72D 1972 Fittipaldi France MIGAS 013 Lotus 98T 1986 Senna free 014 Ferrari 312T 1976 Lauda / Regazzoni 2002, 9/2003, 9/2009 015 Brabham BT 46 1978 Lauda Sweden MIGAS 016 Tyrrell P34 1976 Depallier / Scheckter / Peterson Formule 1 č. 2 017 Ferrari 312T2 1975 Lauda Monaco Formule 1 č. 6 018 Prost AP04 2001 Enge Italy ABC 47/24, 11/2010 019 Ligier JS5 1976 Laffite Formule 1 č. 4 020 McLaren M26 1977 Hunt Canada Lovenbrau 10/2005, 11/2010 021 Ferrari 312T4 1979 Scheckter / Villeneuve Speciál Formule 1 (ABC 11/2003), 3/2005, 11/2009 022 Shadow DN5 1975 Pryce Formule 1 č. 5 023 Tyrrell 006 1973 Stewart Italy 2/2006, 11/2009 024 Tyrrell 003 1971 Stewart chybne označený ako Tyrrell 001 Speciál Formule 1 (ABC 11/2003) 025 McLaren MP4/4 1988 Senna / Prost free, 2002, 2003, 9/2009 026 Lotus 72D 1970 Rindt ABC 48/10 027 Jordan EJ11 2001 Frentzen / Trulli Speciál Formule 1 (ABC 11/2003) 028 McLaren M23 1974 Fittipaldi Speciál Formule 1 (ABC 11/2003), 11/2009 029 March 741 1974 Brambila Formule 1 č. -

Lotus 49 Manual PDF Book

LOTUS 49 MANUAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ian Wagstaff | 168 pages | 24 Nov 2014 | HAYNES PUBLISHING GROUP | 9780857334121 | English | Somerset, United Kingdom Lotus 49 Manual PDF Book Download as PDF Printable version. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. Rating details. Home Contact us Help Free delivery worldwide. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. For the last five years, Minardi was owned by controversial Australian tycoon Paul Stoddart. Gian Carlo Minardi also developed a reputation as a fabulous talent-spotter — Fisichella, Trulli, Webber and the youngest ever World Champion Alonso all started their F1 careers with Minardi. Graham Hill went on to win that year's title and the car continued winning races until Follow us. Skip to main content. Originally these wings were bolted directly to the suspension and were supported by slender struts. Jo Siffert also drove a 49, owned by Rob Walker , to win the British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch that year, the last time a car entered by a genuine privateer won a championship Formula 1 race. Ian Wagstaff is a freelance journalist specialising in motorsport and the automotive components industry. The 49 was an advanced design in Formula 1 because of its chassis configuration. September Ralph Adam Fine, a Judge on the Wisconsin Court of Appeals since , reveals how appellate judges, all over the country in state and federal courts, really decide cases, and how you can use that knowledge to win your appeal.