Japanese Loanwords in Hiragana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rendaku in the Rendaku in the Kahoku Dialect of Yamagata Japan

Novem ber 3rd , 2012 Rendaku in the Kahoku Dialect of Yamagata Japan Mizuki Miyashita - U Montana Timothy J. Vance - NINJAL MkMark IIirwin -YtYamagata UUiniv. ACOL 2012, Lethbridge, AB 1 ACOL 2012 2 Miyashita, Vance, and Irwin Rendaku Morphophonemic phenomenon found mainly in compounds in Japanese. Rendaku in TJ (Tokyo Japanese) /ori/ ‘fold’ /kami/ ‘paper’ /ori + kami/ [origami] ACOL 2012 3 Miyashita, Vance, and Irwin QUESTION How does rendaku surface when a dialect exhibits different voicing contrasts than Tokyo Japanese? Tokyo Yamagata Gloss [mato] [mado] ‘target’ [mado] [mando] ‘window’ [origami] or [oringami]? ACOL 2012 4 Miyashita, Vance, and Irwin Outline Rendaku Background (TJ) YtYamagata (KhkKahoku) dia lec t Yamagata Rendaku Co-existing variations in Yamagata rendaku Dialect Contact Problems toward synchronic analysis ACOL 2012 5 Miyashita, Vance, and Irwin Rendaku in TJ Initial voiceless obstruent is voiced in a compound word (preceded by a vowel) /ori/ ‘fold’ ///kami/ ‘pppaper’ /ori + kami/ [origami] However, rendaku is highly irregular. ACOL 2012 6 Miyashita, Vance, and Irwin Rendaku irregularity Many morphemes do not behave this way, although some cases are systematically constrained for rendaku e.g. Lyman’s Law (Layman 1894). /tori + kago/ [torikago] ‘birdcage’ (bird + cage) * [titorigago] Many morphemes show unpredictable alternation for no apparent reason. e.g. /kami/ ‘hair’ /mae + kami/ [maegami] ‘front hair (= bangs)’ /kuro + kami/ [kurokami] ‘black hair’ ACOL 2012 7 Miyashita, Vance, and Irwin Rendaku irregularity (cont.) Historically speaking, some alternations in TJ involve more than jjgust a voicing difference. That is, /b/ alternates with /h/, not with /p/. (note: /h/ is realized as [ɸ] before [u]) ege.g. -

Fungsi Ateji Dalam Lirik Lagu Pada Album Marginal #4 the Best 「Star Cluster 2」 Produksi Rejet

PARAMASASTRA Vol. 6 No. 1 - Maret 2019 p-ISSN 2355-4126 e-ISSN 2527-8754 http://journal.unesa.ac.id/index.php/paramasastra FUNGSI ATEJI DALAM LIRIK LAGU PADA ALBUM MARGINAL #4 THE BEST 「STAR CLUSTER 2」 PRODUKSI REJET Meisha Putri M.R., Agus Budi Cahyono Universitas Brawijaya, [email protected] Universitas Brawijaya, [email protected] ABSTRACT This article aimed to describe why furigana in Japanese songs often found different furigana actually with kanji below it. Data uses the album MARGINAL # 4 THE BEST 「STAR CLUSTER 2」 REJET Production. This study uses qualitative descriptive to examine the type of ateji based on Lewis's theory (2010) and its function based on the theory of Jakobson (1960). Based on analysis, writer find more contrastive ateji than denotive ateji. Fatigue function is found more than other functions. The metalingual function is found on all data. Keywords: Ateji, Furigana, semantic PENDAHULUAN Huruf bahasa Jepang dibagi menjadi 4 yang digunakan sehari-hari. Adapun huruf tersebut adalah Kanji, Hiragana, Katakana dan Romaji. Pada penulisan huruf Kanji kadang diikuti dengan furigana yang merupakan bantuan cara baca serta memaknai kanji itu sendiri karena huruf kanji kadang mempunyai cara baca yang berbeda. Selain pembubuhan dengan furigana ada juga dengan ateji. Furigana itu murni sebagai cara baca dan makna aslinya, maka ateji adalah bantuan cara baca yang dilekatkan untuk menambahkan lapisan ide maupun makna di dalam kanji itu sendiri. Ateji merupakan penulisan bahasa Jepang yang tidak mengikuti cara baca jion (cara baca kanji China) dan jikun (cara baca kanji Jepang) ataupun jigi (makna asli) bahasa Jepang tersebut (Shirose, 2012: 103). -

Uhm Phd 9506222 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UM! films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent UJWD the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adverselyaffect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-band comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms tnternauonat A Bell & Howell tntorrnatron Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. M148106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800:521·0600 Order Number 9506222 The linguistic and psycholinguistic nature of kanji: Do kanji represent and trigger only meanings? Matsunaga, Sachiko, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 Copyright @1994 by Matsunaga, Sachiko. -

A Bird's-Eye View of Lexical Blending

Introduction: A bird’s-eye view of lexical blending Vincent Renner, François Maniez, Pierre J. L. Arnaud To cite this version: Vincent Renner, François Maniez, Pierre J. L. Arnaud. Introduction: A bird’s-eye view of lexical blending. Vincent Renner ; François Maniez ; Pierre Arnaud. Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Lexical Blending, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-9, 2012, Trends in Linguistics - Studies and Monographs, 978-3-11-028923-7. hal-00799934 HAL Id: hal-00799934 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00799934 Submitted on 13 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Introduction: A bird’s-eye view of lexical blending Vincent Renner, François Maniez, and Pierre J.L. Arnaud 1. A brief retrospective view Lexical blends have been popularized in English by the Victorian author Lewis Carroll, who not only elaborated many new formations made up of word fragments, but also pondered on the process of lexical blending in his writings: Well, “slithy” means “lithe and slimy.” “Lithe” is the same as “active.” You see, it’s like a portmanteau – there are two meanings packed up into one word. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Japanese Native Speakers' Attitudes Towards

JAPANESE NATIVE SPEAKERS’ ATTITUDES TOWARDS ATTENTION-GETTING NE OF INTIMACY IN RELATION TO JAPANESE FEMININITIES THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Atsuko Oyama, M.E. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Master’s Examination Committee: Approved by Professor Mari Noda, Advisor Professor Mineharu Nakayama Advisor Professor Kathryn Campbell-Kibler Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures ABSTRACT This thesis investigates Japanese people’s perceptions of the speakers who use “attention-getting ne of intimacy” in discourse in relation to femininity. The attention- getting ne of intimacy is the particle ne that is used within utterances with a flat or a rising intonation. It is commonly assumed that this attention-getting ne is frequently used by children as well as women. Feminine connotations attached to this attention-getting ne when used by men are also noted. The attention-getting ne of intimacy is also said to connote both intimate and over-friendly impressions. On the other hand, recent studies on Japanese femininity have proposed new images that portrays figures of immature and feminine women. Assuming the similarity between the attention-getting ne and new images of Japanese femininity, this thesis aims to reveal the relationship between them. In order to investigate listeners’ perceptions of women who use the attention- getting ne of intimacy with respect to femininity, this thesis employs the matched-guise technique as its primary methodological choice using the presence of attention-getting ne of intimacy as its variable. In addition to the implicit reactions obtained in the matched- guise technique, people’s explicit thoughts regarding being onnarashii ‘womanly’ and kawairashii ‘endearing’ were also collected in the experiment. -

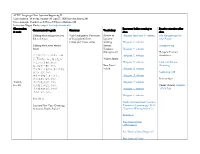

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

The Degree of the Speaker's Negative Attitude in a Goal-Shifting

In Christopher Brown and Qianping Gu and Cornelia Loos and Jason Mielens and Grace Neveu (eds.), Proceedings of the 15th Texas Linguistics Society Conference, 150-169. 2015. The degree of the speaker’s negative attitude in a goal-shifting comparison Osamu Sawada∗ Mie University [email protected] Abstract The Japanese comparative expression sore-yori ‘than it’ can be used for shifting the goal of a conversation. What is interesting about goal-shifting via sore-yori is that, un- like ordinary goal-shifting with expressions like tokorode ‘by the way,’ using sore-yori often signals the speaker’s negative attitude toward the addressee. In this paper, I will investigate the meaning and use of goal-shifting comparison and consider the mecha- nism by which the speaker’s emotion is expressed. I will claim that the meaning of the pragmatic sore-yori conventionally implicates that the at-issue utterance is preferable to the previous utterance (cf. metalinguistic comparison (e.g. (Giannakidou & Yoon 2011))) and that the meaning of goal-shifting is derived if the goal associated with the at-issue utterance is considered irrelevant to the goal associated with the previous utterance. Moreover, I will argue that the speaker’s negative attitude is shown by the competition between the speaker’s goal and the hearer’s goal, and a strong negativity emerges if the goals are assumed to be not shared. I will also compare sore-yori to sonna koto-yori ‘than such a thing’ and show that sonna koto-yori directly expresses a strong negative attitude toward the previous utterance. -

A Home for International Exchange 石川国際交流サロン:異文化交流の家

January 2003 NO.4 Ishikawa Alumni Association NO.4 10th Anniversary of the Ishikawa Foundation for International Exchange! 石川県国際交流協会設立10周年! ●財団法人石川県国際交流協会理事長谷本正憲(石川県知事)より感謝状 ●300名を超える来場者で華やいだ記念式典と講演会の会場 を受けとる浅野三恵子さん(左) ●Mieko Asano(left), receiving a certificate of appreciation from ●Over 300 people attended the memorial ceremony and lecture. the IFIE Executive Director Masanori Tanimoto(Governor of Ishikawa Prefecture). 財団法人石川県国際交流協会は2002年に設立 To commemorate the 10th anniversary of the 10周年を迎え、記念式典や記念講演会をはじめ、 Ishikawa Foundation for International Exchange (IFIE), several international exchange events were held beginning 国際交流に関するイベントが2002年11月16日か with a commemorative ceremony and lecture from the ら22日まで開催された。 16th to the 22nd of November, 2002. 同協会の発展に功績のあった2団体およびホーム Certificates of appreciation were awarded in a com- memorative ceremony to 73 volunteers including host fam- ステイ受け入れボランテアなど73名に対して、記 ilies and two organizations which have contributed greatly 念式典において感謝状が授与された。 to the activities of IFIE. 記念講演には、大学卒業後文部省英語指導主事 The memorial lecture titled, The Japan that I am Fond 助手として山形県で英語教育に携わり、現在はテ of was given by celebrity Daniel Kahl, who after graduat- ing from university, became involved in the teaching of レビなどで幅広く活躍する外国人タレント、ダニ English in Yamagata prefecture as an Assistant Language エル・カール氏を講師に迎え、「私の大好きなニッ Teacher to the Ministry of Education. Currently, he ポン」と題し、山形弁を交えた愉快なトークで聴 delights audiences of Japanese television through his mas- 衆を魅了した。 ter usage of the Yamagata dialect. A panel display, Foreign Countries Seen from the Kaga -

Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms Range: FF00–FFEF

Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms Range: FF00–FFEF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Unconscious Gairaigo Bias in EFL: a Case Study of Japanese Teachers of English

Unconscious Gairaigo Bias in EFL: A Case Study of Japanese Teachers of English Mark Spring Keywords: gairaigo, loanwords, cross-linguistic transfer, bias, traditional teaching 1. Introduction 'Japanese and English speakers find each other's languages hard to learn' (Swan and Smith, 2001: 296). This is probably due in no small part to the many linguistic differences between the seemingly unrelated languages. Huge levels of word borrowing, though, have led to an abundance of loanwords in the current Japanese lexicon, many originating from English. These are known locally in Japan as gairaigo. Indeed, around half of the three thousand most common words in English and around a quarter of those on The Academic Word List (see Coxhead, 2000) correspond in some form to gairaigo (Daulton: 2008: 86). Thus, to some degree we can say that the two languages are 'lexically wed' (ibid: 40). With increasing recognition among researchers of the positive role that the first language plays in the learning of a second, and a growing number of empirical studies indicating gairaigo knowledge can facilitate English acquisition, there have been calls to exploit these loanwords for the benefit of Japanese learners of English. But despite research supporting a role for them in learning English, it is said that 'many or most Japanese teachers of English avoid using gairaigo in the classroom' (Daulton: 2011: 8) due to a 'gairaigo bias' (ibid.). This may stem from unfavourable social attitudes towards loanwords themselves in the Japanese language, and pedagogical concerns over their negative influences on learning. Should this be true, it would represent a position incongruous with the idea of exploiting cross-linguistic lexical similarities. -

A STUDY of L2 KANJI LEARNING PROCESS Analysis of Reading and Writing Errors of Swedish Learners in Comparison with Level-Matched Japanese Schoolchildren

A STUDY OF L2 KANJI LEARNING PROCESS Analysis of Reading and Writing Errors of Swedish Learners in Comparison with Level-matched Japanese Schoolchildren Fusae Ivarsson Department of Languages and Literatures Doctoral dissertation in Japanese, University of Gothenburg, 18 March, 2016 Fusae Ivarsson, 2016 Cover: Fusae Ivarsson, Thomas Ekholm Print: Reprocentralen, Campusservice Lorensberg, Göteborgs universitet, 2016 Distribution: Institutionen för språk och litteraturer, Göteborgs universitet, Box 200, SE-405 30 Göteborg ISBN: 978-91-979921-7-6 http://hdl.handle.net/2077/41585 ABSTRACT Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, 18 March, 2016 Title: A Study of L2 Kanji Learning Process: Analysis of reading and writing errors of Swedish learners in comparison with level-matched Japanese schoolchildren. Author: Fusae Ivarsson Language: English, with a summary in Swedish Department: Department of Languages and Literatures, University of Gothenburg, Box 200, SE-405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden ISBN: 978-91-979921-7-6 http://hdl.handle.net/2077/41585 The present study investigated the characteristics of the kanji learning process of second language (L2) learners of Japanese with an alphabetic background in comparison with level-matched first language (L1) learners. Unprecedentedly rigorous large-scale experiments were conducted under strictly controlled conditions with a substantial number of participants. Comparisons were made between novice and advanced levels of Swedish learners and the respective level-matched L1 learners (Japanese second and fifth graders). The experiments consisted of kanji reading and writing tests with parallel tasks in a practical setting, and identical sets of target characters for the level-matched groups. Error classification was based on the cognitive aspects of kanji.