Archaeological Investigations Ltd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Restoration of Belle Vue Park, Newport by John Woods

No. 53 Winter 2008/09 The restoration of Belle Vue Park, Newport by John Woods Park Square was the first public park to open in Newport. remained intact, the park has developed steadily since the mid Today it lies behind a multi-storey car park of the same name 1890s with the Council adding additional features and on Commercial Street in the heart of the busy city centre. In facilities sometimes as a result of direct public pressure. In the 1880s this little park was reported as mainly serving as a 1896 the Gorsedd Circle was added in readiness for the meeting place and playground for children, but by 1889 , National Eisteddfod which was held in Newport for the first when Councillor Mark Mordey approached the local time in 1897. In the early 1900s , following public pressure , landowner Lord Tredegar, the Corporation clearly had sporting facilities were added: two bowling rinks in 1904 and aspirations to build a public park that befitted the status of tennis courts in 1907. The present-day bowls pavilion was the developing town. built in 1934 and is located centrally between two full size flat In 1891 following the Town Council’s decision “That a bowling greens. Whilst the park pavilion and conservatories public park should be procured for the town in some suitable were completed in readiness for the official opening, the locality” , Lord Tredegar expressed an interest in presenting a demand for additional space for both refreshments and shelter site to Newport . The following year the fields lying between brought about the building of the Rustic Tea House in 1910. -

Springspring 2015 2015 Site

FRIENDSNEWSLETTER Spring 2015 Spring 2015 Spring 2015 Spring Friends of Dyffryn Gardens Newsletter Living at Dyffryn House moved from Canton into Dyffryn and lived there for over two years. during the Second World War The story of these years is told by By Colin Evans Colin Evans, then aged 7 years, as seen through his eyes and that of his In 1937 Inspector Emlyn Evans of the 10 year old brother. Colin later went Glamorgan Police Force was on to a very successful career in appointed officer in charge of Civil education and after his retirement Defence and ARP training for newly wrote his story for his grandchildren. recruited civilian wardens. In 1941 He talked to The Friends of Dyffryn there was a particularly bad German about his memories of this time. air raid on Cardiff when amongst Unfortunately the few photographs other damage the Cathedral and the taken at the time have gone missing. Arms Park were both hit.. As a result A car was provided to take the local officials decided that all family to see their new home and important documents in the City and Emlyn can still see his mother’s County, should be stored away from dismay and her ultimatum that she major risk of damage. The then would only move if the authorities Colonel Traherne, who had recently converted part of the building to an bought Dyffryn from Miss Cory, apartment for the family. This was offered the use of the House. In 1941 duly done utilising the end of the first Inspector Evans was made officer in floor nearest the current walled charge and was expected to live on gardens. -

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY March 2019

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY March 2019 Volume 1 Strategic Framework Monmouth CONTENTS Key messages 1 Setting the Scene 1 2 The GIGreen Approach Infrastructure in Monmouthshire Approach 9 3 3 EmbeddingGreen Infrastructure GI into Development Strategy 25 4 PoSettlementtential GI Green Requirements Infrastructure for Key Networks Growth Locations 51 Appendices AppendicesA Acknowledgements A B SGISources Database of Advice BC GIStakeholder Case Studies Consultation Record CD InformationStrategic GI Networkfrom Evidence Assessment: Base Studies | Abergavenny/Llanfoist D InformationD1 - GI Assets fr Auditom Evidence Base Studies | Monmouth E InformationD2 - Ecosystem from Services Evidence Assessment Base Studies | Chepstow F InformationD3 - GI Needs fr &om Opportunities Evidence Base Assessment Studies | Severnside Settlements GE AcknowledgementsPlanning Policy Wales - Green Infrastructure Policy This document is hyperlinked F Monmouthshire Wellbeing Plan Extract – Objective 3 G Sources of Advice H Biodiversity & Ecosystem Resilience Forward Plan Objectives 11128301-GIS-Vol1-F-2019-03 Key Messages Green Infrastructure Vision for Monmouthshire • Planning Policy Wales defines Green Infrastructure as 'the network of natural Monmouthshire has a well-connected multifunctional green and semi-natural features, green spaces, rivers and lakes that intersperse and infrastructure network comprising high quality green spaces and connect places' (such as towns and villages). links that offer many benefits for people and wildlife. • This Green Infrastructure -

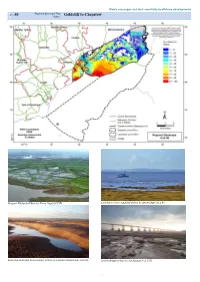

Goldcliff to Chepstow Name

Welsh seascapes and their sensitivity to offshore developments No: 50 Regional Seascape Unit Goldcliff to Chepstow Name: Newport Wetlands (Photo by Kevin Dupé,©CCW) Looking across to England (Photo by Kevin Dupé,©CCW) Extensive sand flats in the estuary (Photo by Charles Lindenbaum ©CCW) Severn Bridge (Photo by Ian Saunders ©CCW) 1 Welsh seascapes and their sensitivity to offshore developments No: 50 Regional Seascape Unit Goldcliff to Chepstow Name: Seascape Types: TSLR Key Characteristics A relatively linear, reclaimed coastline with grass bund sea defences and extensive sand and mud exposed at low tide. An extensive, flat hinterland (Gwent Levels), with pastoral and arable fields up to the coastal edge. The M4 and M48 on the two Severn bridges visually dominate the area and power lines are also another major feature. Settlement is generally set back from the coast including Chepstow and Caldicot with very few houses directly adjacent, except at Sudbrook. The Severn Estuary has a strong lateral flow, a very high tidal range, is opaque with suspended solids and is a treacherous stretch of water. The estuary is a designated SSSI, with extensive inland tracts of considerable ecological variety. Views from the coastal path on bund, country park at Black Rock and the M4 and M48 roads are all important. Road views are important as the gateway views to Wales. All views include the English coast as a backdrop. Key cultural associations: Gwent Levels reclaimed landscape, extensive historic landscape and SSSIs, Severn Bridges and road and rail communications corridor. Physical Geology Triassic rocks with limited sandstone in evidence around Sudbrook. -

Whgt Bulletin Issue 65 July 2013 the Royal British Bowmen Society and the Diversion of Archery

welsh historic gardens trust ~ ymddiriedolaeth gerddi hanesyddol cymru whgt bulletin Issue 65 July 2013 The Royal British Bowmen Society and the diversion of Archery One of the most famous depictions of the Royal British Bowmen Society is the 1822 meeting at Erddig Hall, Wrexham, an engrav- ing after the amateur artist John Townshend of Trevalyn Hall, Rossett. The Bowmen members are distinguished by their uniforms in Lincoln green (associated with Robin Hood and his Merrymen) and yellow. In the centre is the Lady Paramount, Lady Eleanor Grosvenor of Eaton Hall wearing the hat with a plume of white feathers, other members wear black feathers. The small boy in black is said to be General John Yorke (1814-1890) aged 9, the second son of Simon Yorke of Erddig. John Townshend included himself as the young man in the uniform seated with the Lady Paramount. Image courtesy of the British Museum. At the end of the 18th century, long after the bow was I went this morning with my dear Father to Sir used for warfare, archery became a fashionable pastime Ashton Lever’s, where we could not be entertained. Sir amongst the elite. Country houses developed shooting Ashton came and talked to us a good while....He looks grounds and archery lawns within the designed land- fully 60 years old, yet he had dressed not only two young scape. This archaic sport was connected with the taste men, but himself, in a green jacket, a round hat with for medieval romance and chivalry and the stories of green feathers, a bundle of arrows under one arm, and a Robin Hood and Ivanhoe. -

Chepstow Matters

Telephone 01291 606 900 December 2017 Community Chepstow^ Matters Hand delivered FREE to c10,000 homes across Chepstow & the surrounding villages Christmas is coming ... and there are many ways to join in the local celebrations listed inside this month’s issue. Christmas shopping? Plenty of local businesses with great gift ideas ... see inside for more details! THE PERFECT DESTINATIONFOR 01291635555 YOUR BUSINESS... basepoint.co.uk FLEXIBLE MEETING GREAT Formoreinformation WORKSPACE ROOMS FACILITIES FROM 1PERSON FROM ONLY ON SITE PARKING contactustoday UP TO 250 PEOPLE 15 PERHOUR &24/7ACCESS [email protected] @basepoint_chep INSIDE: • Local People • Local Businesses • Local Community Groups & Events Dear Readers... Christmas is almost upon us and, as I go to print on this edition, we are a week away from switching on Contact Us : the Town’s Christmas lights - our front cover depicts scenes from last year’s event. This is Santa’s first 01291 606 900 opportunity of the year to visit Chepstow, and his other scheduled visits are listed on page 7 - keep a [email protected] look out for his sleigh and give him a wave when he [email protected] visits your area! www.mattersmagazines.co.uk This festive edition of your community magazine is Chepstow Matters jam packed with details of all the local Christmas Editor: Jaci Crocombe fairs, concerts, carol and church services that we c/o Batwell Farm, Shirenewton NP16 6RX had received details of at time of going to print. It Reg Office: Matters Magazines Ltd, also contains plenty of Christmas present ideas to 130 Aztec West, Almondsbury BS32 4UB fulfil your shopping needs - Keep it Local and support Co Regn No: 8490434 our local businesses. -

GHS News 86 Summer 2010 3 GHS Events 2010 and Beyond…

THE GA R DEN NEwS HISTO R Y SOCIETY SummER 2010 86 events conservation agenda forum news contents news 4 GHS events 2010 and beyond… 4 conservation notes: England 9 2010 GHS Essay Prize conservation notes: Scotland 10 our new vice-President 12 agenda monrepos Park, Vyborg, Russia 14 The London Geodiversity Project 17 Geodiversity in Scotland 18 Fruit Collections at Brogdale, Kent 20 Bee Boles: an update 21 Parks and Gardens UK 23 Reflections on Water: report 23 wKGN International Forum 2009: report 24 The gardens of Persia: report 25 Paxton House, Berwickshire: a report 27 Chloe Bennett Digitising Gilpin’s 1772 Painshill sketchbook 29 Impressionist Gardens: review 29 Dominic Cole & Lucy Lambton with winner Laura Meyer other events 31 forum Tunduru Botanical Garden 36 In a year which has seen the demise of several key Accessible gardens 36 Garden history courses it is perhaps ironic that Country House and Greenhouses 36 this year’s Annual Essay Competition had many Pyramids 36 more entries than ever before and the standard was A new MA in Garden History? 36 consistently high. After some heated debate the Design a new garden for Astley Castle 37 judges finally agreed on a Winner, with a ‘Highly Courses at Cambridge 37 Commended’ and ‘Special Mention’ certificates Bushy Park Water Gardens 37 also being awarded. The winner receives a year’s Garden History mentioned on TV! 38 The English Gardening School relocates 38 subscription to The Society and a cheque for ‘monster Work’ 38 £250. The prizes were presented by our President what a difference a year makes… 38 Lucinda Lambton at the annual Summer Party at principal officers 39 London’s Geffrey Museum. -

Avon Power Station EIA Scoping Report

Avon Power Station EIA Scoping Report Scottish Power Generation Limited Avon Power Station January 2015 EIA Scoping Report Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 Consenting Regime 3 Objectives of Scoping 3 The Need for the Proposed Development 4 2 Description of the Existing Environment 6 Description of the Site 6 Site surroundings 8 Historic and Existing Site Use 9 Sensitive Environmental Receptors 10 Previous Environmental Studies 11 3 Project Description 12 The Proposed Development 12 Overview of Operation of Combined Cycle Gas Turbines 13 Fast Response Generators 15 Electricity Connection 15 Gas Connection 16 Water Supply Options 16 Water Discharge 17 Access to the Site 17 Potential Rail Spur 17 Carbon Capture Readiness (CCR) 17 Preparation of the Site 18 Construction Programme and Management 19 4 Project Alternatives 20 Alternative Sites 20 Alternative Developments 20 Alternative Technologies 21 5 Planning Policy 22 Primary Policy Framework 22 Secondary Policy Framework 23 6 Potentially Significant Environmental Issues 25 Air Quality 25 Noise and Vibration 28 Ecology 31 Flood Risk, Hydrology and Water Resources 35 Geology, Hydrogeology and Land Contamination 36 Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 38 Traffic and Transport 41 Land Use, Recreation and Socio-Economics 43 Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment 44 Health Impact Assessment 47 Sustainability and Climate Change 47 CHP Assessment 48 Avon Power Station January 2015 EIA Scoping Report CCR Assessment 48 7 Non-Significant EIA Issues 49 Waste 49 Electronic Interference 49 -

PWLLMEYRIC Guide Price £425,000

PWLLMEYRIC Guide price £425,000 . www.archerandco.com To book a viewing call 01291 62 62 62 www.archerandco.comwww.archerandco.com To book a viewing call 01291 62 62 62 PRIORY COTTAGE Pwllmeyric, Chepstow, Monmouthshire NP16 6LE . Charming two bedroomed cottage style bungalow Excellent views over open countryside In very popular location with easy access to M48 motorway . A charming two bedroomed cottage style bungalow dating back to c1920's which has been sympathetically extended, updated and improved over recent years to provide spacious and versatile accommodation situated in the popular village of Pwllmeyric which is located just over one mile to Chepstow Town Centre, which provides primary and senior schools, leisure centre, shops, pubs, restaurants, bus and rail links, approximately 1.5 miles to the M48 Severn Bridge providing excellent commuting to Newport, Cardiff, Bristol, Gloucester and London. Just along the road is the famous St Pierre Golf and Country Club, Chepstow Garden Centre and for those who enjoy walking St Pierre Woods and a variety of countryside walks over open farmland. Mathern is the next village along to Pwllmeyric and boasts its own Gastro Pub, Mathern Palace and the beautiful and ancient St Tewdrics Church dating back to 600 AD. Also within a short driving distance is the beautiful and renowned Wye Valley and Offas Dyke Path which runs along the Welsh and English Border both of which provide a wealth of outdoor pursuits including walking, climbing, cycling and riding, Chepstow and Caldicot Castles and the Cistercian Abbey at Tintern provide places of historical interest locally and also hold occasional seasonal open air entertainment. -

Spadework Spring 11

CONTENTS Chairman’s Report ………………………... 1 Visit to High Glanau …………………......... 2 Morville Hall (lecture) …………………....... 4 Autumn Trip to Anglesey…………………... 6 Plas Newydd House…………………........ 6 Plas Newydd Garden…………………..... 7 Plas Cadnant………………….................. 9 Penrhyn Castle Garden…………………. 12 Bodnant Garden…………………............. 14 Maenan Hall…………………................... 16 Italian Gardens (lecture) …………………... 18 Isfryn Day Lilies (lecture) …………………. 20 Bodnant (lecture) …………………............... 22 Plant DNA & Bee Behaviour (lecture) …… 24 Magic of Roses (lecture) ………………….... 26 Additions to CHS Library………………….. 28 Preview of Summer Outings……………….. 29 Summary of Summer Outings……………... 36 THE DIARY...............................inside back cover Painswick Exedra Mike Hayward www.cardshortsoc.org.uk for latest programme updates 1 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT We belong to a thriving Society that’s underpinned with an excellent committee and constant high membership numbers. However, many of the Society’s members also belong to other groups and societies, sometimes with interests similar to ours, and this can present problems when organizing the CHS trips, as our travel dates and destinations can clash with or duplicate those of the other organizations. We all do some juggling to try to accommodate each other. The trips organized by our Society play an important part in its activities, and in particular provide the opportunity to socialize – something that is not very convenient at the end of a lecture evening. The fixed cost of coach hire will be increasing due to VAT and fuel increases, so the more of you who support the five- day visit and the day trips, the more we can keep the seat prices as low as possible. The feedback forms sent out to members with the AGM minutes will provide the committee with useful information that we can hopefully use in decision making for future outings, so please return these, anonymously if you prefer, to Secretary Dave Hughes with your comments and suggestions. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs The Welsh Clergy 1558-1642 Thesis How to cite: (1999). The Welsh Clergy 1558-1642. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 1998 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000e23c Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk UOL. I YF- L-- ciao The Welsh Clergy 1558 - 1642 Barrie Williams M. A., M. Litt., S.Th. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 1998 Faculty of Arts History Department THE OPEN UNIVERSITY a n-1O2'S NO'. fl'\7O22SZ% etc CCE SVßmýý1Gý1 '. 22 oaCEMS2 E'. ICIq S OQT2 CF IaK. S: l t4 výNlX1' ý! 1c1 Olq CONTENTS VOLUME I Contents I Abstract. Preface Introduction 1 Part 1: The Beneficed Clergy Chapter I: The Welsh Bishops The Elizabethan Settlement 22 The Age of Archbishop Whitgift 45 From the Accession of James I to the Civil War 64+ Chapter 2: The Welsh-Cathedral''jClergy 91 St`Asaph 92 Vicars Choral 96. Bangor 98 Vicars Choral 106 Llandaff 101 St'. rDavld' s 103 Brecon Co ll e'giate Church 107' Llanddewi Brefi 109 Conclusion 114 Appendix : The Life of the Cathedral. -

TOPOGRAPHY of ^Vtat Mvitain, OR, BRITISH TRAVELLER's POCKET DIRECTORY;

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES : TOPOGRAPHY OF ^vtat Mvitain, OR, BRITISH TRAVELLER'S POCKET DIRECTORY; BEING AN ACCURATE AND COUPBEBENSIVE TOPOGRAPHICAL AND STATISTICAL DESCRIPTION OP ALL THE COUNTIES IN WITH THE ADJACENT ISLANDS: II.LUSTRATE0 WITH MAPS OF THE COUNTIES, WHICH FORM A COMPLETE BRITISH ATLAS. BY G. A. COOKE, ESQ. VOL. XIV. CONTAINING MONMOUTHSHIRE AND SOUTH WALES. Uontron Printed^ hjf Alignment from the Executors of the late C. Cooke, FOR SHERWOOD, NEELY, AND JONES, PATERNOSTER-ROW ; AND SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. : A TOPOGRAPHICAL AND STATISTICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTY OF MONMOUTH; Containing an Account of its Situation, i Mines, Canats, Extent, Fisheries, Cariosities, I Towns, Manufactures. Antiquities, I Roads, Commerce, iJiography, I Rivers, - 1 Agriculture, History, Civil and Ecclesiastical Jurisdictions, &c. To which arc prefixed, The Direct and Principal Cross Roads^ Distances ofStages, Jnnsy and Nollemen and Gentlemen's Seats, ALSO, ^ %i^t of tl)t Markets ant< dTair^; AND AN INP/EX TABLE, Eithibiting at one View, the Distances of all the Towns from London, and of Towns from each other With an Account of the Wye Tour. THE WHOLE FORMING A COMPLETE COU^TY ITINERARY. BY G. A. COOKE, ESQ. Illustrated with A MAP OF THE COUNTY, VIEWS, fltc. SECOND EDITION. ILonaon: Printed, by Assignment from the Executors of the late C. Cooke, FOR SHERWOOD, JONES, AND CO. PATERNOSTER-ROW; AND SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. B. M'Millao, Printer, B*w-Strcct, Cov«nt-Garden. (3) 2 (4) C CO rt r Cli .—I s: en O C > ROADS IN MONMOUTHSHIRE. On R.