Matthew Carter: Reflects on Type Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brand Style Guide.Indd

California Baptist University Brand Style Guide CALIFORNIA BAPTIST UNIVERSITY BRAND STYLE GUIDE The CBU Brand A brand is the personality a consumer creates for the organizations or products he or she interacts with. Consumers attribute characteristics to organizations to help themselves understand and then engage or avoid them. Brands can be hopeful, helpful, funny, tired, aloof or cold. Consumers create and revise brand personalities every time they come into contact with the organization. These interactions leave impressions on the consumer’s memory. Visualize the impression a branding iron leaves on the backside of a cow and you begin to appreciate the value of each of your interactions with students, parents, alumni, donors and friends. Consistency is essential to building and maintaining a strong brand for two reasons. First, consumers compare each new interaction to memories of previous interactions. When each successive interaction reinforces previous interactions, brand strength is increased. When interactions conflict with each other, the consumer is left thinking the brand is confused and weak. Second, competition for the consumer’s mind is fierce with organizations competing for milliseconds of their attention through a steady barrage of commercial messages. Consistency in CBU’s message and presentation improves the viewer’s (or listener’s) comprehension and increases the likelihood he or she will understand our message in the brief moment we have to communicate it to them. This guide has been developed to help every member of the CBU workforce (1) understand that he or she IS the CBU brand, and (2) properly and consistently represent the brand in all visual and verbal communications. -

Garamond and the French Renaissance Garamond and the French Renaissance Compiled from Various Writings Edited by Kylie Harrigan for Everyone Ever

Garamond and The French Renaissance Garamond and The French Renaissance Compiled from Various Writings Edited by Kylie Harrigan For Everyone ever Design © 2014 Kylie Harrigan Garamond Typeface The French Renassaince Garamond, An Overview Garamond is a typeface that is widely used today. The namesake of that typeface was equally as popular as the typeface is now when he was around. Starting out as an apprentice punch cutter Claude Garamond 2 quickly made a name for himself in the typography industry. Even though the typeface named for Claude Garamond is not actually based on a design of his own it shows how much of an influence he was. He has his typefaces, typefaces named after him and typeface based on his original typefaces. As a major influence during the 16th century and continued influence all the way to today Claude Garamond has had a major influence in typography and design. Claude Garamond was born in Paris, France around 1480 or 1490. Rather quickly Garamond entered the industry of typography. He started out as an apprentice punch cutter and printer. Working for Antoine Augereau he specialized in type design as well as punching cutting and printing. Grec Du Roi Type The Renaissance in France It was under Francis 1, king of France The Francis 1 gallery in the Italy, including Benvenuto Cellini; he also from 1515 to 1547, that Renaissance art Chateau de Fontainebleau imported works of art from Italy. All this While artists and their patrons in France and and architecture first blossomed in France. rapidly galvanised a large part of the French the rest of Europe were still discovering and Shortly after coming to the throne, Francis, a Francis 1 not only encouraged the nobility into taking up the Italian style for developing the Gothic style, in Italy a new cultured and intelligent monarch, invited the Renaissance style of art in France, he their own building projects and artistic type of art, inspired by the Classical heritage, elderly Leonardo da Vinci to come and work also set about building fine Renaissance commissions. -

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Cloud Fonts in Microsoft Office

APRIL 2019 Guide to Cloud Fonts in Microsoft® Office 365® Cloud fonts are available to Office 365 subscribers on all platforms and devices. Documents that use cloud fonts will render correctly in Office 2019. Embed cloud fonts for use with older versions of Office. Reference article from Microsoft: Cloud fonts in Office DESIGN TO PRESENT Terberg Design, LLC Index MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS A B C D E Legend: Good choice for theme body fonts F G H I J Okay choice for theme body fonts Includes serif typefaces, K L M N O non-lining figures, and those missing italic and/or bold styles P R S T U Present with most older versions of Office, embedding not required V W Symbol fonts Language-specific fonts MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS Abadi NEW ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Abadi Extra Light ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic or bold styles provided. Agency FB MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Agency FB Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic style provided Algerian MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567890 Note: Uppercase only. No other styles provided. Arial MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ -

Typography One Typeface Classification Why Classify?

Typography One typeface classification Why classify? Classification helps us describe and navigate type choices Typeface classification helps to: 1. sort type (scholars, historians, type manufacturers), 2. reference type (educators, students, designers, scholars) Approximately 250,000 digital typefaces are available today— Even with excellent search engines, a common system of description is a big help! classification systems Many systems have been proposed Francis Thibaudeau, 1921 Maximillian Vox, 1952 Vox-ATypI, 1962 Aldo Novarese, 1964 Alexander Lawson, 1966 Blackletter Venetian French Dutch-English Transitional Modern Sans Serif Square Serif Script-Cursive Decorative J. Ben Lieberman, 1967 Marcel Janco, 1978 Ellen Lupton, 2004 The classification system you will learn is a combination of Lawson’s and Lupton’s systems Black Letter Old Style serif Transitional serif Modern Style serif Script Cursive Slab Serif Geometric Sans Grotesque Sans Humanist Sans Display & Decorative basic characteristics + stress + serifs (or lack thereof) + shape stress: where the thinnest parts of a letter fall diagonal stress vertical stress no stress horizontal stress Old Style serif Transitional serif or Slab Serif or or reverse stress (Centaur) Modern Style serif Sans Serif Display & Decorative (Baskerville) (Helvetica) (Edmunds) serif types bracketed serifs unbracketed serifs slab serifs no serif Old Style Serif and Modern Style Serif Slab Serif or Square Serif Sans Serif Transitional Serif (Bodoni) or Egyptian (Helvetica) (Baskerville) (Rockwell/Clarendon) shape Geometric Sans Serif Grotesk Sans Serif Humanist Sans Serif (Futura) (Helvetica) (Gill Sans) Geometric sans are based on basic Grotesk sans look precisely drawn. Humanist sans are based on shapes like circles, triangles, and They have have uniform, human writing. -

Type Design for Typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva

Type design for typewriters: Olivetti by María Ramos Silva Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MA in Typeface Design Department of Typography & Graphic Communication University of Reading, United Kingdom September 2015 The word utopia is the most convenient way to sell off what one has not the will, ability, or courage to do. A dream seems like a dream until one begin to work on it. Only then it becomes a goal, which is something infinitely bigger.1 -- Adriano Olivetti. 1 Original text: ‘Il termine utopia è la maniera più comoda per liquidare quello che non si ha voglia, capacità, o coraggio di fare. Un sogno sembra un sogno fino a quando non si comincia da qualche parte, solo allora diventa un proposito, cio è qualcosa di infinitamente più grande.’ Source: fondazioneadrianolivetti.it. -- Abstract The history of the typewriter has been covered by writers and researchers. However, the interest shown in the origin of the machine has not revealed a further interest in one of the true reasons of its existence, the printed letters. The following pages try to bring some light on this part of the history of type design, typewriter typefaces. The research focused on a particular company, Olivetti, one of the most important typewriter manufacturers. The first two sections describe the context for the main topic. These introductory pages explain briefly the history of the typewriter and highlight the particular facts that led Olivetti on its way to success. The next section, ‘Typewriters and text composition’, creates a link between the historical background and the machine. -

P Font-Change Q UV 3

p font•change q UV Version 2015.2 Macros to Change Text & Math fonts in TEX 45 Beautiful Variants 3 Amit Raj Dhawan [email protected] September 2, 2015 This work had been released under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License on July 19, 2010. You are free to Share (to copy, distribute and transmit the work) and to Remix (to adapt the work) provided you follow the Attribution and Share Alike guidelines of the licence. For the full licence text, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode. 4 When I reach the destination, more than I realize that I have realized the goal, I am occupied with the reminiscences of the journey. It strikes to me again and again, ‘‘Isn’t the journey to the goal the real attainment of the goal?’’ In this way even if I miss goal, I still have attained goal. Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 1 Usage .................................................................................. 1 Example ............................................................................... 3 AMS Symbols .......................................................................... 3 Available Weights ...................................................................... 5 Warning ............................................................................... 5 Charter ....................................................................................... 6 Utopia ....................................................................................... -

User Manual 19HFL5014W Contents

User Manual 19HFL5014W Contents 1 TV Tour 3 13 Help and Support 119 1.1 Professional Mode 3 13.1 Troubleshooting 119 13.2 Online Help 120 2 Setting Up 4 13.3 Support and Repair 120 2.1 Read Safety 4 2.2 TV Stand and Wall Mounting 4 14 Safety and Care 122 2.3 Tips on Placement 4 14.1 Safety 122 2.4 Power Cable 4 14.2 Screen Care 123 2.5 Antenna Cable 4 14.3 Radiation Exposure Statement 123 3 Arm mounting 6 15 Terms of Use 124 3.1 Handle 6 15.1 Terms of Use - TV 124 3.2 Arm mounting 6 16 Copyrights 125 4 Keys on TV 7 16.1 HDMI 125 16.2 Dolby Audio 125 5 Switching On and Off 8 16.3 DTS-HD (italics) 125 5.1 On or Standby 8 16.4 Wi-Fi Alliance 125 16.5 Kensington 125 6 Specifications 9 16.6 Other Trademarks 125 6.1 Environmental 9 6.2 Operating System 9 17 Disclaimer regarding services and/or software offered by third parties 126 6.3 Display Type 9 6.4 Display Input Resolution 9 Index 127 6.5 Connectivity 9 6.6 Dimensions and Weights 10 6.7 Sound 10 7 Connect Devices 11 7.1 Connect Devices 11 7.2 Receiver - Set-Top Box 12 7.3 Blu-ray Disc Player 12 7.4 Headphones 12 7.5 Game Console 13 7.6 USB Flash Drive 13 7.7 Computer 13 8 Videos, Photos and Music 15 8.1 From a USB Connection 15 8.2 Play your Videos 15 8.3 View your Photos 15 8.4 Play your Music 16 9 Games 18 9.1 Play a Game 18 10 Professional Menu App 19 10.1 About the Professional Menu App 19 10.2 Open the Professional Menu App 19 10.3 TV Channels 19 10.4 Games 19 10.5 Professional Settings 20 10.6 Google Account 20 11 Android TV Home Screen 22 11.1 About the Android TV Home Screen 22 11.2 Open the Android TV Home Screen 22 11.3 Android TV Settings 22 11.4 Connect your Android TV 25 11.5 Channels 27 11.6 Channel Installation 27 11.7 Internet 29 11.8 Software 29 12 Open Source Software 31 12.1 Open Source License 31 2 1 TV Tour 1.1 Professional Mode What you can do In Professional Mode ON, you can have access to a large number of expert settings that enable advanced control of the TV’s state or to add additional functions. -

The Monotype Library Opentype Edition

en FR De eS intRoDuction intRoDuction einFühRung pReSentación Welcome to The Monotype Library, OpenType Edition; a renowned Bienvenue à la Typothèque Monotype, Édition OpenType; une collection Willkommen bei Monotype, einem renommierten Hersteller klassischer Bienvenido a la biblioteca Monotype, la famosa colección de fuentes collection of classic and contemporary professional fonts. renommée de polices professionnelles classiques et contemporaines. und zeitgenössischer professioneller Fonts, die jetzt auch im OpenType- profesionales clásicas y contemporáneas, ahora también en formato Format erhältlich sind. OpenType. The Monotype Library, OpenType Edition, offers a uniquely versatile La Typothèque Monotype, Édition OpenType propose une collection range of fonts to suit every purpose. New additions include eye- extrêmement souple de polices pour chaque occasion. Parmi les Die Monotype Bibliothek, die OpenType Ausgabe bietet eine Esta primera edición de la biblioteca Monotype en formato OpenType catching display faces such as Smart Sans, workhorse texts such as nouvelles polices, citons des polices attrayantes destinées aux affichages einzigartig vielseitige Sammlung von Fonts für jeden Einsatz. Neben ofrece un gran repertorio de fuentes cuya incomparable versatilidad Bembo Book, Mentor and Mosquito Formal plus cutting edge Neo comme Smart Sans, des caractères très lisibles comme Bembo Book, den klassischen Schriften werden auch neue Schriftentwicklungen wie permite cubrir todas las necesidades. Entre las nuevas adiciones destacan Sans & Neo Tech. In this catalogue, each typeface is referenced by Mentor et Mosquito Formal, et des polices de pointe comme Neo die Displayschrift Smart Sans, Brotschriften wie Bembo Book, Mentor llamativos caracteres decorativos como Smart Sans, textos básicos classification to help you find the font most suitable for your project. -

The Begingreek Package

The begingreek package Claudio Beccari – claudio dot beccari at gmail dot com Version v.1.5 of 2015/02/16 Contents 5 The new greek environment 3 1 Introduction 1 6 The command \greektxt 4 2 Usage 2 7 Font shapes and series 4 8 Examples 5 3 Incomplete fonts and differ- ent encoding 3 9 Acknowledgements 5 4 Default font control 3 10 The code 6 Abstract This small extension module defines the environment greek to be used with pdfLaTeX so as to imitate the similar environment defined in polyglossia. A corresponding command, \greektxt, is also defined. Of course there are some differences, but it has been used extensively and it is useful. 1 Introduction When using pdfLaTeX and babel, language changes are done with babel’s lan- guage switching commands \selectlanguage, \foreignlanguage or with the environments otherlanguage and otherlanguage*. They work fine, but some- times it is better to have a more “agile” command or environment that can be used at least in place of the last three commands or environments. Some more extra functionalities may be desirable, such as the possibility of specifying a different default font family or to switch font family for a particular stretch of Greek text. This small module does exactly what is described above; it has been created only to be used with pdfLaTeX, therefore if it gets loaded with a package that will be run with XeLaTeX or LuaLaTex it will complain loudly and its loading will be aborted; no, not simply that: the only way to exit from this wrong situation is to quit compilation. -

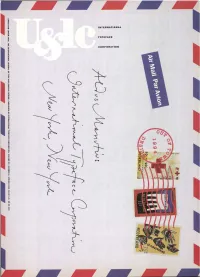

INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION, to an Insightful 866 SECOND AVENUE, 18 Editorial Mix

INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION TYPEFACE UPPER AND LOWER CASE , THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF T YPE AND GRAPHI C DESIGN , PUBLI SHED BY I NTE RN ATIONAL TYPEFAC E CORPORATION . VO LUME 2 0 , NUMBER 4 , SPRING 1994 . $5 .00 U .S . $9 .90 AUD Adobe, Bitstream &AutologicTogether On One CD-ROM. C5tta 15000L Juniper, Wm Utopia, A d a, :Viabe Fort Collection. Birc , Btarkaok, On, Pcetita Nadel-ma, Poplar. Telma, Willow are tradmarks of Adobe System 1 *animated oh. • be oglitered nt certain Mrisdictions. Agfa, Boris and Cali Graphic ate registered te a Ten fonts non is a trademark of AGFA Elaision Miles in Womb* is a ma alkali of Alpha lanida is a registered trademark of Bigelow and Holmes. Charm. Ea ha Fowl Is. sent With the purchase of the Autologic APS- Stempel Schnei Ilk and Weiss are registimi trademarks afF mdi riot 11 atea hmthille TypeScriber CD from FontHaus, you can - Berthold Easkertille Rook, Berthold Bodoni. Berthold Coy, Bertha', d i i Book, Chottiana. Colas Larger. Fermata, Berthold Garauannt, Berthold Imago a nd Noire! end tradematts of Bern select 10 FREE FONTS from the over 130 outs Berthold Bodoni Old Face. AG Book Rounded, Imaleaa rd, forma* a. Comas. AG Old Face, Poppl Autologic typefaces available. Below is Post liedimiti, AG Sitoploal, Berthold Sr tapt sad Berthold IS albami Book art tr just a sampling of this range. Itt, .11, Armed is a trademark of Haas. ITC American T}pewmer ITi A, 31n. Garde at. Bantam, ITC Reogutat. Bmigmat Buick Cad Malt, HY Bis.5155a5, ITC Caslot '2114, (11 imam.