Charter Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

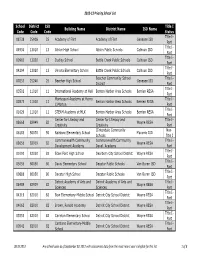

Priority School List

2012‐13 Priority School List School District ISD Title I Building Name District Name ISD Name Code Code Code Status Title I- 08738 25908 25 Academy of Flint Academy of Flint Genesee ISD Part Title I- 04936 13010 13 Albion High School Albion Public Schools Calhoun ISD Part Title I- 00965 13020 13 Dudley School Battle Creek Public Schools Calhoun ISD Part Title I- 04294 13020 13 Verona Elementary School Battle Creek Public Schools Calhoun ISD Part Beecher Community School Title I- 00253 25240 25 Beecher High School Genesee ISD District Part Title I- 03502 11010 11 International Academy at Hull Benton Harbor Area Schools Berrien RESA Part Montessori Academy at Henry Title I- 00373 11010 11 Benton Harbor Area Schools Berrien RESA C Morton Part Title I- 01629 11010 11 STEAM Academy at MLK Benton Harbor Area Schools Berrien RESA Part Center for Literacy and Center for Literacy and Title I- 08668 82949 82 Wayne RESA Creativity Creativity Part Clintondale Community Non- 06183 50070 50 Rainbow Elementary School Macomb ISD Schools Title I Commonwealth Community Commonwealth Community Title I- 08656 82919 82 Wayne RESA Development Academy Devel. Academy Part Title I- 01092 82030 82 Edsel Ford High School Dearborn City School District Wayne RESA Part Title I- 05055 80050 80 Davis Elementary School Decatur Public Schools Van Buren ISD Part Title I- 00888 80050 80 Decatur High School Decatur Public Schools Van Buren ISD Part Detroit Academy of Arts and Detroit Academy of Arts and Title I- 08489 82929 82 Wayne RESA Sciences Sciences Part Title I- 04319 82010 82 Bow Elementary-Middle School Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Part Title I- 04062 82010 82 Brown, Ronald Academy Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Part Title I- 05553 82010 82 Carleton Elementary School Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Part Carstens Elementary-Middle Title I- 00542 82010 82 Detroit City School District Wayne RESA School Part 08.19.2013 Any school open as of September 30, 2012 with assessment data from the most recent year is eligible for this list. -

School State 11TH STREET ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL KY 12TH

School State 11TH STREET ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL KY 12TH STREET ACADEMY NC 21ST CENTURY ALTERNATIVE MO 21ST CENTURY COMMUNITY SCHOOLHOUSE OR 21ST CENTURY CYBER CS PA 270 HOPKINS ALC MN 270 HOPKINS ALT. PRG - OFF CAMPUS MN 270 HOPKINS HS ALC MN 271 KENNEDY ALC MN 271 MINDQUEST OLL MN 271 SHAPE ALC MN 276 MINNETONKA HS ALC MN 276 MINNETONKA SR. ALC MN 276-MINNETONKA RSR-ALC MN 279 IS ALC MN 279 SR HI ALC MN 281 HIGHVIEW ALC MN 281 ROBBINSDALE TASC ALC MN 281 WINNETKA LEARNING CTR. ALC MN 3-6 PROG (BNTFL HIGH) UT 3-6 PROG (CLRFLD HIGH) UT 3-B DENTENTION CENTER ID 622 ALT MID./HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 FARMINGTON HS. MN 917 HASTINGS HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 LAKEVILLE SR. HIGH MN 917 SIBLEY HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 SIMLEY HIGH SCHOOL SP. ED. MN A & M CONS H S TX A B SHEPARD HIGH SCH (CAMPUS) IL A C E ALTER TX A C FLORA HIGH SC A C JONES HIGH SCHOOL TX A C REYNOLDS HIGH NC A CROSBY KENNETT SR HIGH NH A E P TX A G WEST BLACK HILLS HIGH SCHOOL WA A I M TX A I M S CTR H S TX A J MOORE ACAD TX A L BROWN HIGH NC A L P H A CAMPUS TX A L P H A CAMPUS TX A MACEO SMITH H S TX A P FATHEREE VOC TECH SCHOOL MS A. C. E. AZ A. C. E. S. CT A. CRAWFORD MOSLEY HIGH SCHOOL FL A. D. HARRIS HIGH SCHOOL FL A. -

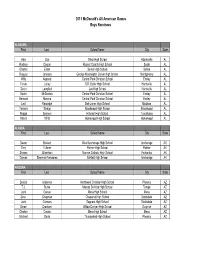

2011 Combined Nominee List

2011 McDonald's All American Games Boys Nominees ALABAMA First Last School Name City State Alex Carr Minor High School Adamsville AL Rodney Cooper Russell County High School Seale AL Charles Eaton Selma High School Selma AL Roquez Johnson George Washington Carver High School Montgomery AL Willy Kouassi Central Park Christian School Ensley AL Trevor Lacey S.R. Butler High School Huntsville AL Devin Langford Lee High School Huntsville AL Kevin McDaniels Central Park Christian School Ensley AL Bernard Morena Central Park Christian School Ensley AL Levi Randolph Bob Jones High School Madison AL Tavares Sledge Brookwood High School Brookwood AL Reggie Spencer Hillcrest High School Tuscaloosa AL Marvin Whitt Homewood High School Homewood AL ALASKA First Last School Name City State Devon Bookert West Anchorage High School Anchorage AK Trey Fullmer Palmer High School Palmer AK Shayne Gilbertson Monroe Catholic High School Fairbanks AK Damon Sherman-Newsome Bartlett High School Anchorage AK ARIZONA First Last School Name City State Dakota Anderson Northwest Christian High School Phoenix AZ T.J. Burke Marcos De Niza High School Tempe AZ Jahii Carson Mesa High School Mesa AZ Zeke Chapman Chaparral High School Scottsdale AZ Jack Connors Saguaro High School Scottsdale AZ Deion Crockom Willow Canyon High School Surprise AZ Charles Croxen Mesa High School Mesa AZ Michael Davis Thunderbird High School Phoenix AZ 2011 McDonald's All American Games Boys Nominees Conor Farquharson Shadow Mountain High School Phoenix AZ Cameron Forte McClintock High School -

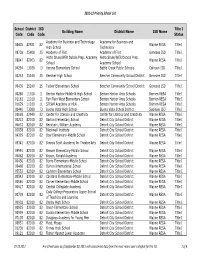

Priority Schools

2011‐12 Priority School List School District ISD Title I Building Name District Name ISD Name Code Code Code Status Academy for Business and Technology Academy for Business and 08435 82921 82 Wayne RESA Title I High School Technology 08738 25908 25 Academy of Flint Academy of Flint Genesee ISD Title I Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. 08047 82903 82 Wayne RESA Title I School Academy School 04294 13020 13 Verona Elementary School Battle Creek Public Schools Calhoun ISD Title I 00253 25240 25 Beecher High School Beecher Community School District Genesee ISD Title I 00439 25240 25 Tucker Elementary School Beecher Community School District Genesee ISD Title I 00286 11010 11 Benton Harbor Middle & High School Benton Harbor Area Schools Berrien RESA Title I 01181 11010 11 Fair Plain West Elementary School Benton Harbor Area Schools Berrien RESA Title I 01629 11010 11 STEAM Academy at MLK Benton Harbor Area Schools Berrien RESA Title I 00440 73080 73 Buena Vista High School Buena Vista School District Saginaw ISD Title I 08668 82949 82 Center for Literacy and Creativity Center for Literacy and Creativity Wayne RESA Title I 00213 82010 82 Barton Elementary School Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Title I 06631 82010 82 Beckham, William Academy Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Title I 02058 82010 82 Blackwell Institute Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Title I 04319 82010 82 Bow Elementary-Middle School Detroit City School District Wayne RESA Title I 09341 82010 82 Brenda Scott Academy for Theatre -

Middle School Target Improvement Target Target Target Target Other Academic Status Indicator Target

State Name LEA Name LEA NCES ID School Name School NCES ID Reading Reading Math Math Elementary/ Graduation Rate School Title I School Proficiency Participation Proficiency Participation Middle School Target Improvement Target Target Target Target Other Academic Status Indicator Target MICHIGAN Battle Creek Public Schools 2600005 Battle Creek Central High School 260000503830 All Not All All Not All Not All Focus Title I schoolwide eligible school- No program MICHIGAN Battle Creek Public Schools 2600005 Valley View Elementary School 260000503847 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Battle Creek Public Schools 2600005 Verona Elementary School 260000503848 Not All All All All All Priority Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Bessemer Area School District 2600006 Washington School 260000603855 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN St. Ignace Area Schools 2600012 LaSalle High School 260001203862 All Not All All Not All All Focus Title I targeted assistance eligible school-No program MICHIGAN Wayne-Westland Community School District 2600015 Albert Schweitzer Elementary School 260001503880 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Wayne-Westland Community School District 2600015 Alexander Hamilton Elementary School 260001503881 All All All All All Priority Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Wayne-Westland Community School District 2600015 David Hicks School 260001503885 Not All All Not All All All Priority Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Wayne-Westland Community School District 2600015 Adlai Stevenson Middle School 260001503905 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Bad Axe Public Schools 2600017 Bad Axe Middle School 260001703919 All All All All All Focus Title I schoolwide school MICHIGAN Joseph K. -

Detroit and Area Schools

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! Lake St. Clair Detroit School Index ! ! 313 311 ! ! ! ! ! 1 Oakland International Academy - Intermediate Berkle!y ! ! 2 ! Casa Richard Academy ! 696 ! ! ! ¨¦§ ! 3 Aisha Shule/WEB Dubois Prep. Academy School 696 Lathrup ! Roseville ! 4 Plymouth Educational Center ¨¦§ ! !Madison ! ! 3 5 Nataki Talibah Schoolhouse of Detroit 10 Village Royal ! "" 6 Michigan Technical Academy Elementary "" ! Heights ! ! ! ! Oak Center ! 7 Martin Luther King, Jr. Education Center Academy ! 696 ! ¦¨§75 ! ! ! Line 8 Woodward Academy ¨¦§ Huntington 9 Cesar Chavez Academy Elementary ! ! ! ! ! ! Woods ! ! ! 10 Cesar Chavez Middle School ! 11 Nsoroma Institute ! ! ! 12 Winans Academy High School ! 696 ! "9"7 13 Detroit Community Schools-High School ¨¦§ ! 14 Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences ! 696 y ! ! ! w ¨¦§ H St Clair 15 Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences Middle School ! k ! ! ! ! Pleasant c 16 Dove Academy of Detroit ! e Shores ! ! b 17 Timbuktu Academy of Science and Technology Ridge s !Eastpointe Farmington ! ! !! ! 305 e ! 18 George Crockett Academy Southfield ! ! o 308 ! ! r ! 19 P!ierre ToussaHinitl Alscademy ! G ! ! 314 ! 20 Voyageur Academy ¤£24 ! 21 Hope Academy 304 Hazel ! Warren ! ! ! Oak Park ! 315 ! ! 22 Weston Preparatory Academy ! !! Park ! ! Ferndale ! ! ! 23 Edison Public School Academy ! ! ! ! ! 24 David Ellis Academy ! ! 303 ! Fa2r5m Rinogssto-Hnill Academy-Elementary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 26 Ross-Hill Academy-High ! ! 27 Center for Literacy and Creativity ! ! 28 UnGiversal Academy ! !ra ! ! ! 29 DRetrointd -

High School Registration Summary

High School Registration Summary Participating in the Michigan e-Transcript Initiative will help ensure that schools may retain their federal stimulus dollars under the America Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. During e-Transcript registration, a school staff member selected one of four phases to complete the installation, testing and training steps. The phases are depicted below: Installation Phases Phase Start End 1 December 1, 2009 February 28, 2010 2 March 1, 2010 May 31, 2010 3 June 1, 2010 August 31, 2010 4 September 1, 2010 November 30, 2010 When viewing this registration summary, you will notice that schools fall into one of nine statuses: Status Definition Installing The school received the installation instructions, is currently installing the software and sending test transcripts. Troubleshooting Docufide and/or the school are working on an issue regarding the student information system. Non-compliant The school sent the test transcripts, but is missing the student Unique Identification Code, building code and/or district code, labeled (format) as UIC, BCODE and DCODE, respectively. The school has been notified of these missing fields and Docufide is awaiting new test files to be sent. Non-compliant The school has not completed registration by the December 31, 2009 deadline or has not become "live" with the service in the selected phase. Pending training The school has completed the software installation and the transcripts contain the three required fields. The staff members at the school who will process transcripts still need to attend the online training. Unresponsive The school has received the installation instructions, but did not install the software and/or send test transcripts. -

In This Issue: • MIAAA Exemplary Athletic Program Award Recipients Grosse Pointe • Executive Committee Meetings North and Saginaw Heritage

In This Issue: • MIAAA Exemplary Athletic Program Award Recipients Grosse Pointe • Executive Committee Meetings North and Saginaw Heritage • Representative Council Meeting • Athletic Equity Committee Meeting • 2003-04 MHSAA Budget • Ski Committee Meeting • 2002-03 MHSAA Audit • Volleyball Committee Meeting • “Legends of the Games” Honors First • Lacrosse Committee Meeting Girls Basketball Champions December 2003/January 2004 Volume LXXX BULLETIN Number 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page November Executive Committee Meeting . 252 Executive Committee Teleconference Meeting . 255 December Executive Committee Meeting . 255 Representative Council Meeting. 261 Lacross Officials Needed . 267 From the Executive Director: Do It Again . 268 Eligibility Advancement Reminders. 268 It’s About Team! Not So Meaningless TD . 269 Westdorp, Uyl To Join MHSAA Staff . 270 Who Receives MHSAA Communications? . 271 Scholar-Athlete Award Reminders . 271 2003-04 MHSAA Budget . 272 2002-03 MHSAA Auditor’s Report . 272 MHSAA Repot of Activities 2002-03. 282 Policy for Team Sports Alternate Sites During MHSAA Tournaments. 283 Mandatory Association Membership for MHSAA Tournament Officials . 284 Quick Reference Calendar Corrections. 285 MHSAA Tournament Entry Change Proposal . 286 2003 Fall Coach Ejection List. 287 Schools With Three or More Officials Reports-Fall 2003 . 288 Officials Reports Summary. 288 Girls Basketball CHAMPS Clinic. 289 MIAAA Honors Fourth Exemplary Program Class . 290 First-Ever MHSAA Girls Basketball Champs Honored in Legends Program . 292 2004 Swimming and Diving Finals Sites and Dates. 295 2004 Girls Competitive Cheer Regionals & Final Sites . 296 2004 Gymnastics Regionals & Final Sites . 296 2004 Individual Wrestling Final Sites. 296 2004 LP Team Wrestling Regional Pairings. 297 2004 LP Team Wrestling Quarterfinal, Semifinal and Final Pairings . -

Very Simplified All Schools Ranked

Top to Bottom List of all Schools Determined by mathematics and English language arts achievement and improvement scores 6/23/2010 Statewide combined math/ELA achievement/improve ment percentile District Name Building Name ranking Forest Hills Public Schools Eastern Middle School 100.0 Detroit City School District Cooley North Wing 99.9 Detroit City School District Kettering West Wing 99.9 Grand Rapids Public Schools City Middle/High School 99.9 Forest Hills Public Schools Northern Hills Middle School 99.8 Bloomfield Hills School District Conant Elementary School 99.8 Saginaw City School District Saginaw Arts and Sciences Academy 99.8 Livonia Public Schools Holmes Middle School 99.7 Okemos Public Schools Kinawa Middle School 99.7 Grand Blanc Community Schools City School 99.7 Birmingham City School District Birmingham Covington School 99.6 Forest Hills Public Schools Ada Vista Elementary School 99.6 Homer Community Schools Homer Middle School 99.6 North Muskegon Public Schools North Muskegon High School 99.5 Novi Community School District Novi Middle School 99.5 Forest Hills Public Schools Central Middle School 99.5 Livonia Public Schools Webster Elementary School 99.4 DeWitt Public Schools DeWitt Junior High School 99.4 Forest Hills Public Schools Northern Trails 5/6 School 99.4 East Grand Rapids Public Schools East Grand Rapids Middle School 99.3 Okemos Public Schools Okemos High School 99.3 Houghton-Portage Township Schools Houghton Central High School 99.2 Utica Community Schools Eisenhower High School 99.2 Okemos Public Schools Chippewa -

ED422966.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 422 966 IR 057 168 TITLE Directory of Michigan Libraries, 1998-1999. INSTITUTION Michigan Library, Lansing. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 164p.; Supersedes earlier editions, see ED 418 733, ED 403 885, and ED 390 429. AVAILABLE FROM Library of Michigan, Public Information Office, P.O. Box 30007, Lansing, MI 48909. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Libraries; Branch Libraries; Depository Libraries; Elementary Secondary Education; Higher Education; *Libraries; Library Associations; Library Networks; *Library Services; Public Libraries; Regional Libraries; Special Libraries; State Libraries IDENTIFIERS *Michigan ABSTRACT This directory provides information about various types of Michigan libraries. The directory is divided into 14 sections: (1) "Alphabetical List of Public and Branch Libraries Whose Names do Not Indicate Their Location"; (2) "Public and Branch Libraries"; (3) "Library Cooperatives"; (4) "Academic Libraries"; (5) "Regions of Cooperation"; (6) "Regional Educational Media Centers"; (7) "Regional and Subregional Libraries"; (8) "Michigan Documents Depository Libraries";(9) "Federal Documents Depository Libraries";(10) "Michigan State Agency Libraries"; (11) "Special Libraries";(12) "Library Associations";(13) "School Libraries"; and (14) "Directory Update Form." Alphabetized in some sections by city and in some sections by title of organization, each entry includes address, phone and fax numbers, and a contact name, which is most often a director. For many of the listings, telecommunications-device-for-the-deaf (TDD) number, and electronic mail addresses are offered as well. Hours of operation are provided for public libraries and branch libraries. For many of the academic library listings, Web sites are included. Functioning as a search aid, an introductory section features cross-references to city or town listings from many public library names that do not mention or describe the library's location. -

Michigan Department of Community Health Mercury-Free Schools in Michigan

Michigan Department of Community Health Mercury-Free Schools in Michigan Entity Name City Eastside Middle School Bay City Trinity Lutheran School St. Joseph A.D. Johnston Jr/Sr High School Bessemer Abbot School Ann Arbor Abbott Middle School West Bloomfield Academic Transitional Academy Port Huron Academy for Business and Technology Elementary Dearborn Ada Christian School Ada Ada Vista Elementary Ada Adams Christian School Wyoming Adams Elementary School Bad Axe Adams Middle School Westland Adlai Stevenson Middle School Westland Adrian High School Adrian Adrian Middle School 5/6 Building Adrian Adrian Middle School 7/8 Building Adrian Airport Senior High School Carleton Akiva Hebrew Day School Southfield Akron-Fairgrove Elem. School Akron Akron-Fairgrove Jr/Sr High School Fairgrove Alaiedon Elementary School Mason Alamo Elementary School Kalamazoo Albee Elementary School Burt Albert Schweitzer Elementary School Westland Alcona Elementary School Lincoln Alcona Middle School Lincoln Alexander Elementary School Adrian Alexander Hamilton Elementary School Westland All Saints Catholic School Alpena Allegan High School Allegan Allegan Street Elementary School Otsego Allen Elementary School Southgate Allendale Christian School Allendale Allendale High School Allendale Allendale Middle School Allendale Alma Middle School Alma Alma Senior High School Alma Almont Middle School Almont Alpena High School Alpena Alward Elementary School Hudsonville Amberly Elementary School Portage Amerman Elementary School Northville Anchor Bay High School Fair Haven Anchor Bay Middle School North New Baltimore Anderson Elementary School Bronson Anderson Middle School Berkley Andrew G. Schmidt Middle School Fenton Andrews Elementary School Three Rivers Angell School Ann Arbor Angelou, Maya Elementary School Detroit Angling Road Elementary School Portage Angus Elementary School Sterling Heights Ann Arbor Open at Mack School Ann Arbor Ann J. -

School District School Name Adams Twp School District

SCHOOL DISTRICT SCHOOL NAME ADAMS TWP SCHOOL DISTRICT JEFFERS JR SR HIGH SCHOOL SOUTH RANGE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL AIRPORT CMTY SCHOOL DISTRICT AIRPORT SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL EDITH WAGAR MIDDLE SCHOOL FRED W RITTER ELEM SCHOOL HENRY NIEDERMEIER ELEM SCHOOL JOSEPH STERLING ELEM SCHOOL LOREN EYLER PRIMARY SCHOOL AKRON FAIRGROVE SCHOOL DIST AKRON FAIRGROVE ELEMENTARY SCH AKRON FAIRGROVE JR SR HIGH SCH ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOL DIST ALLEN PARK CMTY SCHOOL ALLEN PARK HIGH SCHOOL ALLEN PARK MIDDLE SCHOOL ARNO ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BENNIE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL LINDEMANN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ALLENDALE SCHOOL DISTRICT ALLENDALE HIGH SCHOOL ALLENDALE MIDDLE SCHOOL EVERGREEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL NEW OPTIONS SPRINGVIEW ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ALMONT CMTY SCHOOL DISTRICT ALMONT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL ALMONT HIGH SCHOOL ALMONT MIDDLE SCHOOL ORCHARD PRIMARY SCHOOL ARVON TWP SCHOOL DISTRICT ARVON TWP SCHOOL AUTRAIN ONOTA PUBLIC SCHOOLS AUTRAIN ONOTA SCHOOL AVONDALE SCHOOL DISTRICT WOODLAND ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BAD AXE PUBLIC SCHOOL DIST BAD AXE HIGH SCHOOL BAD AXE INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL BAD AXE JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL GEORGE E GREENE ELEM SCHOOL BANGOR TWP SCHOOL DISTRICT 8 WOOD SCHOOL BARAGA AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT BARAGA HIGH SCHOOL PELKIE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PHILIP LATENDRESSE ELEM SCHOOL BARK RIVER HARRIS SCH DIST BARK RIVER HARRIS ELEM SCHOOL BARK RIVER HARRIS HIGH SCHOOL BAY CITY PUBLIC SCHOOL DIST AUBURN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL HAMPTON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL KOLB ELEMENTARY SCHOOL LINSDAY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL MACGREGOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL MACKENSEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL WASHINGTON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BEDFORD PUBLIC