Journal of Neolithic Archaeology [email protected] Imphal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

A RECONSTRUCTION of PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R

A RECONSTRUCTION OF PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R. Mortensen University of Pittsburgh James A. Miller Independent Scholar This paper presents a reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic, the putative ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages, a Tibeto-Burman subgroup. A reconstructed rhyme inventory for the proto-language is presented. Correspondence sets for each of the members of the inventory are then systematically presented, along with supporting cognate sets drawn from four Tangkhulic languages: Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, and Tusom. This paper also summarizes the major sound changes that relate Proto-Tangkhulic to the daughter languages on which the reconstruction is based. It is concluded that Proto-Tangkhulic was considerably more conservative than any of these languages. It preserved the Proto-Tibeto-Burman length distinction in certain contexts and reflexes of final *-l, even though these are not preserved as such in Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, or Tusom. Proto-Tangkhulic is argued to be a potentially useful source of evidence in the reconstruction of Proto-Tibeto- Burman. Tangkhulic, comparative reconstruction, rhymes, vowel length 1. INTRODUCTION The goal of this paper is to present a preliminary reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic (PT), the ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages of Manipur and contiguous parts of India and Burma. It will show that Proto- Tangkhulic was a relatively conservative daughter language of Proto-Tibeto- Burman, preserving final *-l, and the vowel length distinction (in some contexts), among other features. As such, we suggest that Proto-Tangkhulic has significant importance in understanding the history of Tibeto-Burman. 1.1. The Tangkhulic language family All Tangkhulic languages are spoken in a compact area centered around Ukhrul District, Manipur State, India. -

E:\CBCNEI\Baptist News\64

Contents Baptist News A quarterly news letter of the COUNCIL OF BAPTIST CHURCHES IN NORTH EAST INDIA Editorial 2 The Council comprises Assam Love for Perfect Unity 4 Baptist Convention, Arunachal Put on Love for Perfect 8 Baptist Church Council, Garo Unity in Mission Baptist Convention, Karbi Anglong Baptist Convention, Leaders & Pastors 10 Manipur Baptist Convention Conference and Nagaland Baptist Church The Book of Luke: 15 Council. Hope, Purpose, Redemption EDITORIAL BOARD The first Woman Pastor 25 Editor: Rev Dr A. K. Lama Installed in the Church Assistant Editor: Ms Kaholi Zhimomi in Assam Sub-Editors: News Clippings 27 Dr Asangla Ao Mr Atungo Shitri A Memorable Picnic 39 Design & Layout: Siamliana Khiangte Former CBCNEI 42 Circulation: Missionary & Staff Jatin Gogoi “Can We Imagine A 44 Jinoy G. Sangma World Without Books” Babul Boro In His Footsteps 47 Subscription: CBCNEI Archive and 53 One Year ` 150 (US$20) Library Two Years ` 250 (US$35) Three Years ` 400 (US$50) Naga Christian 55 Five Years ` 600 (US$80) Fellowship, Chennai Contact information: From the Assistant 60 CBCNEI, Mission Compound Editor Panbazar, Guwahati, Assam-781001 Phone: +91-361-2515 829 (O) Fax: +91-361-2544 447 eMail: [email protected] website: www.cbcnei.in Baptist News, JanuarFacebook:y - March 2013 facebook.com/cbcnei 1 from the desk of editor Dear friend, The theme of the year 2013 for CBCNEI family is Put on Love for the perfect unity (Col 3:14). As followers of Jesus Christ, we are called to be the people of the BOOK but we are also called to be the people of the LOVE. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

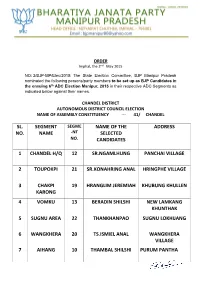

Sl. No. Segment Name Name of the Selected Candidates

ORDER Imphal, the 2nd May 2015 NO: 2/BJP-MP/Elec/2015: The State Election Committee, BJP Manipur Pradesh nominated the following persons/party members to be set up as BJP Candidates in the ensuing 6th ADC Election Manipur, 2015 in their respective ADC Segments as indicated below against their names. CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 41/ CHANDEL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 CHANDEL H/Q 12 SR.NGAMLHUNG PANCHAI VILLAGE 2 TOUPOKPI 21 SR.KONAHRING ANAL HRINGPHE VILLAGE 3 CHAKPI 19 HRANGLIM JEREMIAH KHUBUNG KHULLEN KARONG 4 VOMKU 13 BERADIN SHILSHI NEW LAMKANG KHUNTHAK 5 SUGNU AREA 22 THANKHANPAO SUGNU LOKHIJANG 6 WANGKHERA 20 TS.ISMIEL ANAL WANGKHERA VILLAGE 7 AIHANG 10 THAMBAL SHILSHI PURUM PANTHA 8 PANTHA 11 H.ANGTIN MONSANG JAPHOU VILLAGE 9 SAJIK TAMPAK 23 THANGSUANKAP GELNGAI VILAAGE 10 TOLBUNG 24 THANGKHOMANG AIBOL JOUPI VILLAGE HAOKIP CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 42/ TENGNOUPAL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 KOMLATHABI 8 NG.KOSHING MAYON KOMLATHABI VILLAGE 2 MACHI 2 SK.KOTHIL MACHI VILLAGE, MACHI BLOCK 3 RILRAM 5 K.PRAKASH LANGKHONGCHING VILLAGE 4 MOREH 17 LAMTHANG HAOKIP UKHRUL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 43/ PHUNGYAR SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 GRIHANG 19 SAUL DUIDAND GRIHANG VILLAGE KAMJONG 2 SHINGKAP 21 HENRY W. KEISHING TANGKHUL HUNDUNG 3 KAMJONG 18 C.HOPINGSON KAMJONG BUNGPA KHULLEN 4 CHAITRIC 17 KS.GRACESON SOMI PUSHING VILLAGE 5 PHUNGYAR 20 A. -

Megaliths in Ancient India and Their Possible Association to Astronomy1

MEGALITHS IN ANCIENT INDIA AND THEIR POSSIBLE ASSOCIATION TO ASTRONOMY1 Mayank N. Vahia Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, India And Manipal Advanced Research Group, Manipal University Manipal – 576104, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected] Srikumar M. Menon Faculty of Architecture, Manipal Institite of Technology Manipal – 576104, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected] Riza Abbas Indian Rock Art Research Centre, Nashik (a division of Indian Numismatic, Historical and Cultural Research Foundation), Nashik E-mail: [email protected] Nisha Yadav Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, India E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The megalithic monuments of peninsular India, believed to have been erected in the Iron Age (1500BC – 200AD), can be broadly categorized into sepulchral and non-sepulchral in purpose. Though a lot of work has gone into the study of these monuments since Babington first reported megaliths in India in 1823, not much has been understood about the knowledge systems extant in the period these were built – in science and engineering, especially mathematics and astronomy. We take a brief look at the archaeological understanding of megaliths, before taking a detailed assessment of a group of megaliths (in the south Canara region of Karnataka state in South India) that were hitherto assumed to be haphazard clusters of menhirs. Our surveys have indicated positive correlation of sight-lines with sunrise and sunset points on the horizon for both summer and winter solstices. We identify 5 such monuments in the region and present the survey results for one of the sites, demonstrating the astronomical implications. We also discuss the possible use of the typologies of megaliths known as stone alignments/avenues as calendar devices. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

The Emergence of Obstruents After High Vowels 1. Introduction

The Emergence of Obstruents after High Vowels 1. Introduction Vennemann (1988) and others have argued that sound changes which insert segments most commonly do so in a manner that “improves” syllable structure: they provide syllables with onsets, allow consonants that would otherwise be codas to syllabify as onsets, relieve hiatus between vowels, and so on. On the other hand, the deletion of consonants seems to be particularly common in final position, a tendency that is reflected not only in the diachronic mechanisms outlined by Vennemann, but also reified in synchronic mechanisms like the Optimality Theoretic NoCoda constraint (Prince and Smolensky 1993). It may seem surprising, then, that there is small but robust class of sound changes in which obstruents (usually stops, but sometimes fricatives) emerge after word-final vowels. Discussions of individual instances of this phenomenon have periodically appeared in the literature. The best-known case is from Maru (a Tibeto-Burman language closely related to Burmese) and was discovered by Karlgren (1931), Benedict (1948), and Burling (1966; 1967). Ubels (1975) independently noticed epenthetic stops in Grassfields Bantu languages and Stallcup (1978) discussed this development in another Grassfields Bantu language, Moghamo, drawing an explicit parallel to Maru. Blust (1994) presented the most comprehensive treatment of these sound changes to date (in the context of making an argument about the unity of vowel and consonant features). To the Maru case, he added two additional instances from the Austronesian family: Lom (Belom) and Singhi. He also presented two historical scenarios through which these changes could occur: diphthongization and “direct hardening” of the terminus of the vowel. -

September 2019 JULY-SEPTEMBER 2019 Inside 02 03 from the Director’S Desk JULY-SEPTEMBER 2019

Quarterly Newsletter July - September 2019 JULY-SEPTEMBER 2019 Inside 02 03 From the Director’s Desk JULY-SEPTEMBER 2019 Current me frame, July to September, 2019, Addion of terracoa Paphal of Manipur under the FROM THE DIRECTOR’S DESK Page 03 is marked by mulple significant events which had direcon N. Sakamacha Singh, our curatorial official EXHIBIT OF THE MONTH huge impact on our visitors as well as social network and renovaon of Galo House of Arunachal under Khambana Kao Phaba - A Painng on Canvas Page 04 plaorm. We could organised a field trip, naonal the leadership of Ms.Nyayir Riba given us immense Damba/ Nagada - Tradional Percussion Instrument Page 05 level seminar and an exhibion on Loktak lake of sasfacon as these became visitors delight. EXHIBITIONS Manipur. Prof. K.K Basa, a Tagore naonal fellow of The naonal level seminar on 'Ethnographic Periodical Exhibion- “Island Cultures of India” Page 06 IGRMS, also joined in such a well thought out Museums of India', perhaps remained one of the Renovaon of tradional house type of Galo Community of Arunachal Pradesh Page 07 programme and Salam Rajesh, a well known local finest academic discourses in IGRMS which has Book Exhibion on Yoga Page 08 scholar from Manipur, could lead us in our valuable benefied resource persons, parcipants and well Art Exhibion - Under the theme "Single Use of Plasc" Page 09 field documentaon by local boats to floang as curatorial officials. In NEI and beyond, we could Open Air Exhibion: Anji Paphal Page 10 houses of Loktak lake. Our exhibion was take mulple iniaves with various academic instuons. -

Laos' Plain of Menhirs

Laos’ Plain of Menhirs The formal conservation process for the Houaphanh menhirs has been underway for nearly twenty years. What has actually been accomplished during this period, and how are the material condition of the landscape and the artefacts now, compared with the situation between 1999 and 2002 when the authors did research on the menhirs and designed/installed interpretive signage at the site? Alan Potkin and Catherine Raymond report. At least 1,500 years ago, people whose origin and fate we know almost nothing of have erected hundreds of menhirs along 10 km of summit trails atop forested mountains in the present Houaphanh province, eastern Laos. Three lower saddles were favoured for the main menhir fields, linked one to the next by isolated menhir clusters. The menhirs themselves, in the form of long and narrow blades, are plaques of cut schist erected upright, one behind the other, with the tallest often in the middle. Interspersed among the groups of menhirs, in no discernable order are burial chambers set deep in the bedrock. Access to the ..................................................... SPAFA Journal Vol. 22 No. 2 1 opening below was often through a narrow vertical chimney equipped with steps. Each of these was covered by an enormous stone disk up to several metres in diametre. In 1931, the sites around San Kong Phan were surveyed and partially excavated by a team from Ecole Française d’Extrême- Orient (EFEO), led by archaeologist Madeleine Colani (Colani 1932). With four decades of bitter warfare soon to follow, the Houaphanh menhirs were not further researched until 2001, when it became known that an international development project providing vehicular access to isolated upland communities that had been dependent on opium production, inadvertantly caused substan- tive damage – both directly and indirectly – to several of the menhir sites. -

Stonehenge and Megalithic Europe

Alan Mattlage, February 1st. 1997 Stonehenge and Megalithic Europe Since the 17th century, antiquarians and archeologists have puzzled over Stonehenge and similar megalithic monuments. Our understanding of these monuments and their builders has, however, only recently gone beyond very preliminary speculation. With the advent of radiocarbon dating and the application of a variety of sciences, a rough picture of the monument builders is slowly taking shape. The remains of deep sea fish in Mesolithic trash heaps indicate that northern Europeans had developed a sophisticated seafaring society by 4500 BC. The subsequent, simultaneous construction of megalithic monuments in Denmark-Sweden, Brittany, Portugal, and the British Isles indicates the geographic distribution of the society's origins, but eventually, monument construction occurred all across northwestern Europe. The monument builders' way of life grew out of the mesolithic economy. Food was gathered from the forest, hunted, or collected from the sea. By 4000 they began clearing patches of forest to create an alluring environment for wild game as well as for planting crops. This marks the start of the Neolithic period. Their material success produced the first great phase of megalithic construction (c. 4200 to 3200). The earliest monuments were chambered tombs, built by stacking enormous stones in a table-like structures, called "dolmens," which were then covered with earth. We call the resulting tumuli a "round barrow." Local variations of this monument-type can be identified. Elaborate "passage graves" were built in eastern Ireland. Elaborate "passage graves" were built in eastern Ireland. These were large earthen mounds covering a corridor of stones leading to a corbeled chamber.