Laos' Plain of Menhirs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

Megaliths in Ancient India and Their Possible Association to Astronomy1

MEGALITHS IN ANCIENT INDIA AND THEIR POSSIBLE ASSOCIATION TO ASTRONOMY1 Mayank N. Vahia Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, India And Manipal Advanced Research Group, Manipal University Manipal – 576104, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected] Srikumar M. Menon Faculty of Architecture, Manipal Institite of Technology Manipal – 576104, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected] Riza Abbas Indian Rock Art Research Centre, Nashik (a division of Indian Numismatic, Historical and Cultural Research Foundation), Nashik E-mail: [email protected] Nisha Yadav Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, India E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The megalithic monuments of peninsular India, believed to have been erected in the Iron Age (1500BC – 200AD), can be broadly categorized into sepulchral and non-sepulchral in purpose. Though a lot of work has gone into the study of these monuments since Babington first reported megaliths in India in 1823, not much has been understood about the knowledge systems extant in the period these were built – in science and engineering, especially mathematics and astronomy. We take a brief look at the archaeological understanding of megaliths, before taking a detailed assessment of a group of megaliths (in the south Canara region of Karnataka state in South India) that were hitherto assumed to be haphazard clusters of menhirs. Our surveys have indicated positive correlation of sight-lines with sunrise and sunset points on the horizon for both summer and winter solstices. We identify 5 such monuments in the region and present the survey results for one of the sites, demonstrating the astronomical implications. We also discuss the possible use of the typologies of megaliths known as stone alignments/avenues as calendar devices. -

Stonehenge and Megalithic Europe

Alan Mattlage, February 1st. 1997 Stonehenge and Megalithic Europe Since the 17th century, antiquarians and archeologists have puzzled over Stonehenge and similar megalithic monuments. Our understanding of these monuments and their builders has, however, only recently gone beyond very preliminary speculation. With the advent of radiocarbon dating and the application of a variety of sciences, a rough picture of the monument builders is slowly taking shape. The remains of deep sea fish in Mesolithic trash heaps indicate that northern Europeans had developed a sophisticated seafaring society by 4500 BC. The subsequent, simultaneous construction of megalithic monuments in Denmark-Sweden, Brittany, Portugal, and the British Isles indicates the geographic distribution of the society's origins, but eventually, monument construction occurred all across northwestern Europe. The monument builders' way of life grew out of the mesolithic economy. Food was gathered from the forest, hunted, or collected from the sea. By 4000 they began clearing patches of forest to create an alluring environment for wild game as well as for planting crops. This marks the start of the Neolithic period. Their material success produced the first great phase of megalithic construction (c. 4200 to 3200). The earliest monuments were chambered tombs, built by stacking enormous stones in a table-like structures, called "dolmens," which were then covered with earth. We call the resulting tumuli a "round barrow." Local variations of this monument-type can be identified. Elaborate "passage graves" were built in eastern Ireland. Elaborate "passage graves" were built in eastern Ireland. These were large earthen mounds covering a corridor of stones leading to a corbeled chamber. -

Prehistoric Western Art 40,000 – 2,000 BCE

Prehistoric Western Art 40,000 – 2,000 BCE Introduction Prehistoric Europe was an evolving melting pot of developing cultures driven by the arrival of Homo sapiens, migrating from Africa by way of southwest Asia. Mixing and mingling of numerous cultures over the Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic periods in Europe stimulated the emergence of innovative advancements in farming, food preparation, animal domestication, community development, religious traditions and the arts. This report tracks European cultural developments over these prehistoric periods, Figure 1 Europe and the Near East emphasizing each period’s (adapted from Janson’s History of Art, 8th Edition) evolving demographic effects on art development. Then, representative arts of the periods are reviewed by genre, instead of cultural or timeline sequence, in order to better appreciate their commonalities and differences. Appendices identify Homo sapien roots in Africa and selected timeline events that were concurrent with prehistoric human life in Europe. Prehistoric Homo Sapiens in Europe Genetic, carbon dating and archeological evidence suggest that our own species, Homo sapiens, first appeared between 150 and 200 thousand years ago in Africa and migrated to Europe and Asia. The earliest archeological finds that exhibit all the characteristics of modern humans, including large rounded brain cases and small faces and teeth, date to 190 thousand years ago at Omo, Ethiopia. 1 IBM announced in 2011 that the Genographic Project, charting human genetic data, supports a southern route of human migration from Africa via the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait in Arabia, suggesting a role for Southwest Asia in the “Out of Africa” expansion of modern humans. -

A Dolmen in the Talmud

10 A DOL~iE~ l~ THE TALMUD. 34. Festuca ovina,-var. pinifolia. Hackel in litt., Flor. Or., V, 617. Higher Lebanon. 35. Scleropoa maritima. L. Sp. 128.-Coast near Sidon. 36. Bromusflabellatus. Hack., Boiss., Flor. Or., V, 648.-Near Jeru- salem. 37. Bromus alopecurus. Poir. Voy., II, 100.-Galilee and the coast. 38. Bromus squm-ros1ts.-L. Sp. 112.-Lebanon. 39. Bromus brachystachys. Hornung. Fl., XVI, 2, p. 418.-By the Jordan. 40. Brachypodium pinnatum. L. Sp. 115.-Lower Lebanon. 41. Agropyrum panormitanum. Pari. PI., var. Sic. II, p. 20.-Hermon. 42. Agropyrum repens. L. Sp. 128.-Lebanon. 43 . Agropyrum elongatum. Hort., Gr. Austr., II, 15.-Near Beyrout. 44. ..!Egilops bicornis. Forsk., Descr., 26.-Sandy places, coast. 45. Psilurus nardoides. 'frin. Fund., I, 73.-Coast and interior. 46. Hordeum secalinum. Schreb. Spic., 148.-'fhe Lejah. 47. Elymus delileanus. Schultz. Mant., 2, 424.-nentral Palestine. H. B. 'fRISTRAM. Durham, 26th November, 1884. A DOLMEN IN THE TALMUD. " RABBI IsHMAEL said, 'Three stones beside each other at the side of the image of Markulim are forbidden, but two are allowed. But the wise say when they are within his view they are forbidden, but when they are not within his view they are allowed.'" (Mishnah Aboda Zarah, iv, l.) This passage from the tract treating of "Strange Worship" refers to the idolatry of the second and third centuries A.D., before the establish ment of Christianity by Constantine. R. Ishmael was a contemporary of Akiha (circa 135 A.D.). From the Babylonian Talmud (Baba Metzia 25 b) we learn that· these three stones near the "Menhir of Mercury" (for Markulim was Mercury or Herrnes, the god of the pillar) were arranged two side by side and the third laid flat across. -

The Yamnaya Impact North of the Lower Danube: a Tale of Newcomers and Locals, Bulletin De La Société Préhistorique Française, 117, 1, P

Preda-Bǎlǎnicǎ B., Frînculeasa A., Heyd V. (2020) – The Yamnaya Impact North of the Lower Danube: A Tale of Newcomers and Locals, Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 117, 1, p. 85-101. The Yamnaya Impact North of the Lower Danube A Tale of Newcomers and Locals Bianca Preda-Bal ˘ anic ˘ a, ˘ Alin Frînculeasa, Volker Heyd Abstract: This paper aims to provide an overview of the current understanding in Yamnaya burials from north of the Lower Danube, particularly focussing on their relationship with supposed local archaeological cultures/socie- ties. Departing from a decades-long research history and latest archaeological finds from Romania, it addresses key research basics on the funerary archaeology of their kurgans and burials; their material culture and chronology; on steppe predecessors and Katakombnaya successors; and links with neighbouring regions as well as the wider southeast European context. Taking into account some reflections from latest ancient DNA revelations, there can be no doubt a substantial migration has taken place around 3000 BC, with Yamnaya populations originating from the Caspian-Pontic steppe pushing westwards. However already the question if such accounts for the term of ’Mass Migrations’ cannot be satisfactorily answered, as we are only about to begin to understand the demographics in this process. A further complication is trying to assess who is a newcomer and who is a local in an interaction scenario that lasts for c. 500 years. Identities are not fixed, may indeed transform, as previous newcomers soon turn into locals, while others are just visitors. Nevertheless, this well-researched region of geographical transition from lowland eas- tern Europe to the hillier parts of temperate Europe provides an ideal starting point to address such questions, being currently also at the heart of the intense discussion about what is identity in the context of the emerging relationship of Archaeology and Genetics. -

Megalithic Monuments in Thrissur in Historical Perspective

Rural South Asian Studies, Vol. 1, No.1, 2015 MEGALITHIC MONUMENTS IN THRISSUR IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Valsa .M.A, Asst. Professor, Dept. of History Little Flower College, Guruvayoor-Kerala ABSTRACT: Megalithic monuments are the main archaeological findings of Kerala to reinterpret her past history. Pre historic period can reconstruct with the help of archaeological evidences .Thrissur district is fortunate to have a large number of megalithic sites. Megalithic monuments like Kudakkallu, Toppikkallu, Menhir, Dolmen, Port-holed cist, Stone alignment, Rock-cut caves etc. transfers us to her past. Sifting through Archaeological evidences to reconstruct and reinterpret the history of Kerala during the megalithic period is a challenge that has to be met. This paper makes an attempt to investigate the various types of megalithic monuments in Thrissur district and their historical significance. Key Words: Dolmen, Kudakkallu, Megalithic Monuments, Menhir, Toppikkallu INTRODUCTION ‘Megaliths’ are the monuments built of granite rocks erected over the burials. The contribution of Kerala to the cultural heritage of India stands unique in every sense. Recent findings in various parts of Kerala has provided enough proof of its greater antiquity in the geological features and pre-historic cultures. The prehistoric evidences obtained from Kerala constitute various culture beginning from Paleolithic to megalithic period. The first set of people of Kerala, can be identified only with reference to their burial practices. These people constructed burial monuments in granite, laterite and pottery, most of which are strikingly similar to the megalithic monuments of west Europe and Asia. Kerala is rich in megalithic monuments, Viz. rock-cut caves, rock-cut pits, urn burials, Umbrella stones (Kudakkallu), hat stones (Toppikkallu), slab cists, Port-holed cists, dolmens, menhirs, multiple hood stones and stone circles. -

Prehistoric Tombs & Standing Stones

PREHISTORIC TOMBS & STANDING STONES OF WESSEX & BRITTANY JUST ANNOUNCED: After-hours, inner circle access to Stonehenge has been granted for this tour! May 7 - 18, 2019 (12 days) with prehistorian Paul G. Bahn Explore the extraordinary prehistoric sites of Wessex, England, and Brittany, France. Amidst beautiful landscapes see world renowned, as well as lesser known, Neolithic and Bronze Age megaliths and monuments such as enigmatic rings of giant standing stones and remarkable chambered tombs. Explore medieval churches, charming villages, museum collections, and more. Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur. © DBauch Highlights include: • Stonehenge, the world’s most famous megalithic site, which is a • The UNESCO World Heritage site of Mont- UNESCO World Heritage site together with Avebury, a unique Saint-Michel, an imposing abbey built on a tidal Neolithic henge that includes Europe’s largest prehistoric stone circle. island. • Enigmatic chambered tombs such as West Kennet Long Barrow. • Charming villages, medieval churches, and • Carnac, with more than 3,000 prehistoric standing stones, the beautiful landscapes of coastlines and rolling hills. world’s largest collection of megalithic monuments. • The uninhabited island of Gavrinis, with a magnificent passage tomb that is lined with elaborately engraved, vertical stones. SOUTHERN ENGLAND • Several outstanding museum collections including prehistoric London necklaces, pendants, polished stone axes, and more. Avebury Devizes Itinerary Durrington Walls (B)= Breakfast, (L)= Lunch, (D)= Dinner Stonehenge Tuesday, May 7, 2019: Depart HOME Salisbury 3 Portsmouth Wednesday, May 8: Arrive London, ENGLAND | Salisbury, Wessex | # of Hotel Nights Welcome Dinner Arrive at London’s Heathrow Airport (LHR), where you will be met and transferred to our hotel in the historic city of Salisbury. -

Sheet 3 the Bronze

Goonhilly: a walk through history Linking the Lizard Countryside Partnership Sheet 3 THE BRONZE AGE Cruc Draenoc Barrow Overlooked by the imposing modern technology of the Earth Charlie Johns, Station satellite dishes sits Dry Tree Menhir. It may be small Senior compared to ‘Arthur’, but it dwarfs the Earth Station in terms of Archaeologist, its history: it dates back to the Early Bronze Age (about 2150 to Cornwall Council 1500 BC), when it sat at the centre of a ritual landscape of barrows built by the prehistoric settlers of the Downs. Goonhilly Dry Tree Menhir: soldiers’ efforts. The Cruc Draenoc menhir is made of There are no recorded barrow: Find yourself gabbro from the Crousa We don’t know what the Downs stone circles on The at the top of Cruc Downs, over two miles were called in the Bronze Age - Lizard, and Dry Tree Draenoc barrow [H], away: the journey to Menhir [H] is one of the near to Dry Tree Menhir, the name Dry Tree is more recent bring it to Goonhilly few standing stones. It is and you are standing on and is thought to refer to a wouldn’t have been thanks to Sir Courtenay the highest point of the quite as spectacular as gallows that may once have stood Vyvyan of Trelowarren Downs: on a good day that for Stonehenge, but near the menhir. There is, and Colonel Serecold of you can see as far as the still quite an effort. however, plenty of archaeological Rosuic that the menhir is St Austell granite standing at all. -

Two Figures (Menhirs) by Barbara Hepworth

Two Figures (Menhirs) c. 1954–1955 Barbara Hepworth THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO Department of Learning and Public Engagement Division of School Programs Crown Family Educator Resource Center Barbara Hepworth’s Two Figures (Menhirs) represents the Barbara Hepworth artist’s fusion of geometry and nature. The teak sculpture is composed of two vertical forms that are situated on a platform and punctuated by white-painted circular or oval concavities. (English, 1903–1975) These upright forms could represent persons, menhirs, or sim- ply shapes. Hepworth’s sculpture merges two major aspects of twentieth-century sculpture by referring to abstract geometry and the organic qualities of the figure and nature. Hepworth, born in 1903 in Yorkshire, England, determined Two Figures (Menhirs), at the age of sixteen that she wanted to be a sculptor. She subsequently won a scholarship to Leeds School of Art in 1919, 1954–1955 where she met Henry Moore, five years her senior, who was to become her lifelong friend and colleague. Another scholar- Teak and paint ship sent Hepworth to the prestigious Royal College of Art in London, where she spent three years. It was during this period 144.8 x 61 x 44.4 cm (57 x 24 x 17.5 in.) that Hepworth and Moore made their first attempts at carving in stone. In so doing, they were working against the prevailing Bequest of Solomon B. Smith, 1986.1278 method of producing sculpture, namely building up a form through modeling. Because the modeled form is constructed by adding clay, this process is called additive, whereas carv- ing is referred to as a subtractive technique. -

2000 Years Before Stonehenge: the Almendres Megalithic Site the Solitary Stones: the Monte Dos Almendres Menhir the Megalithic C

1 2000 years before Stonehenge: the Almendres megalithic site The Almendres site is the largest megalithic monument in the Iberian Peninsula and one of the oldest of Humanity's monuments. It was, it would seem, built around 7000 years ago, at the dawn of the Neolithic, the time when the first communities of shepherds and farmers were emerging in Europe. The Almendres site, whose original layout was, very probably, a horseshoe shape, open towards the east, seems to have been added to and altered: the monument's current shape, which is relatively complex, is partially the result of these old interventions and, also to more or less recent amputations and disturbances. The monument currently comprises around a hundred monoliths, some of which are decorated. The choice of the places where the monuments were positioned surely took into account the physical structure of the landscape, especially the river network as well as the most notable astronomical phenomena, relating to the annual movement of the Sun, Moon, on the horizon. On the outskirts of Évora, in a restricted area to the West of the city, there are two other sites of the same type Portela de Mogos and Vale Maria do Meio. This group makes up the largest concentration of menhirs in the Iberian Peninsula, demonstrating the special role that this region played in the origins of European megalithism. 2 The solitary stones: The Monte dos Almendres menhir As with most of the European megalithic regions, in this area there are a large number of isolated menhirs, some of which appear to be spatially oriented with the sites and generally contemporaneous to them. -

Quelle Différence Existe-T-Il Entre Un Dolmen Et Un Menhir ?

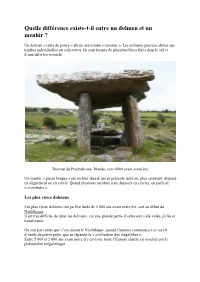

Quelle différence existe-t-il entre un dolmen et un menhir ? Un dolmen « table de pierre » abrite une tombe « tumulus ». Les dolmens peuvent abriter des tombes individuelles ou collectives. Ils sont formés de plusieurs blocs fixés dans le sol et d’une dalle horizontale. Dolmen de Poulnabrone, Irlande, vers 4000 avant notre ère. Un menhir « pierre longue » est un bloc dressé qui se présente isolé ou, plus rarement, disposé en alignement ou en cercle. Quand plusieurs menhirs sont disposés en cercles, on parle de « cromlechs ». Les plus vieux dolmens Les plus vieux dolmens ont pu être datés de 5 000 ans avant notre ère, soit au début du Néolithique. Il est très difficile de dater les dolmens, car une grande partie d’entre eux a été vidée, pillée et transformée. On sait par contre que c’est durant le Néolithique, quand l’homme commença à se servir d’outils de pierre polie, que se répandit la « civilisation des mégalithes ». Entre 5 000 et 2 000 ans avant notre ère environ, toute l’Europe côtière est touchée par le phénomène mégalithique. Dolmen dans les Cornouailles. Les centres les plus anciens se trouvent à l'ouest de la France et au Portugal. Au Portugal, les tumulus recouvrent des chambres de pierre, précédées d’un petit couloir. Ces chambres contiennent une dizaine de squelettes. Dolmen de Zambujeiro au Portugal. En Bretagne, Barnenez, mesure plus de 70 m de long et recouvre quinze chambres funéraires. Les fouilles ont prouvé que le tertre qui le recouvre avait été édifié en deux fois, mais il a été impossible aux archéologues d’étudier les squelettes dissous par le sol acide.