Megalithic Monuments in Thrissur in Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur City District from 12.06.2016 to 18.06.2016

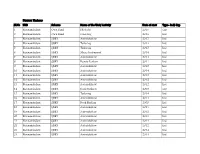

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur City district from 12.06.2016 to 18.06.2016 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KOLAPPULLY HOUSE, 2078/16 U/S TOWN EAST 12.06.2016 M K AJAYAN, SI BAILED BY 1 RAGESH K R RAJAN 29 MALE MULAYAM P O, DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR at 00.15 OF POLICE POLICE VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) AMBATT HOUSE, 2079/16 U/S TOWN EAST 12.06.2016 M K AJAYAN, SI BAILED BY 2 VARGHESE A T THOMAS 46 MALE MULAYAM P O , DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR at 00.22 OF POLICE POLICE VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) MELAYIL HOUSE, 2080/16 U/S TOWN EAST RAMACHAND 12.06.2016 M K AJAYAN, SI BAILED BY 3 RAMAN 47 MALE MULAYAM P O , DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR RAN at 00.30 OF POLICE POLICE VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) MULLOOKKARAN 2081/16 U/S T OWN EAST 12.06.2016 M.K. AJAYAN, BAILED BY 4 SHIJI RAPPAI 39 MALE HOUSE, MULAYAM DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR AT 00.29 SI OF POLICE POLICE VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) PALUKKASSERY 2082/16 U/S TOWN EAST CHANDRASEKH 12.06.2016 M K AJAYAN, SI BAILED BY 5 RAJKUMAR 48 MALE HOUSE, MULAYAM P DIVANJIMOOLA 15(C) R/W 63 PS (THRISSUR ARAN at 00.50 OF POLICE POLICE O , VALAKKAVU ABKARAI ACT CITY) THACHATTIL HOUSE,NEAR 2084/16 U/S TOWN EAST V.K. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thrissur City District from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Thrissur City district from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 MARUTHOOR KARTHIAYA Thrissur HOUSE, NI TEMPLE 23-01-2021 RAMACHA 33, 80/2021 U/s West BYJU K.C. SI BAILED BY 1 RAGHU KARTHIAYANI ROAD at 22:05 NDRAN Male 151 CrPC (Thrissur OF POLICE POLICE TEMPLE, AYYANTHO Hrs City) AYYANTHOLE LE Thrissur ODAYIL 23-01-2021 122/2021 U/s RADHAKRI 36, NR KALYAN East ANUDAS .K, BAILED BY 2 RAKESH (H),KUTTUMUKKU at 23:00 279 IPC & 185 SHNAN Male JEWELLERS (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE , THRISSUR Hrs MV ACT City) Koothumakkal 23-01-2021 71/2021 U/s Peramangal 48, BAILED BY 3 Sreekumar Appu House, Varadiyam at 20:15 118(e) of KP am (Thrissur Sreejith S I Male POLICE Peringottukara Hrs Act City) CHOONDAKARA Thrissur N (H), NEAR 23-01-2021 26, 121/2021 U/s East ANUDAS .K, BAILED BY 4 THOMAS PAULSON THOTTAPPADY, SAPNA at 20:35 Male 279, 283 IPC (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE ANCHERY, THEATRE Hrs City) THRISSUR ERATH (H), Thrissur 23-01-2021 119/2021 U/s 27, VALARKAVU, BTR ITC East ANUDAS .K, BAILED BY 5 SANOOP SUNIL at 19:00 279 IPC & 185 Male NAGAR, JUNCTION (Thrissur SI OF POLICE POLICE Hrs MV ACT KURIACHIRA City) KEEDAM KUNNATH(H)THI 51/2021 U/s PAZHAYA NIZAMUDDI 23-01-2021 GOPALAKR RAMAKRIS 39, RUVADI,PUDUKK PAZHAYAN 279 IPC & NNUR N J, BAILED BY 6 at -

Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church

Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church SABHA PRATHINIDHI MANDALAM 2017 - 2020 Address List of Mandalam Members Report Date: 09/06/2017 DIOCESE - KUNNAMKULAM - MALABAR DIOCESE Page 1 of 4 C012 (KUNNAMKULAM - MALABAR C025 (CHUNGATHARA SALEM) C035 (MAR THOMA COLLEGE, DIOCESE) REV. JOLLY THOMAS CHUNGATHARA) RT. REV. DR. THOMAS MAR THEETHOS SALEM MAR THOMA CHURCH, REV. MATHAI JOSEPH EPISCOPA - BURSAR, MAR THOMA COLLEGE, MAR THOMA CENTRE, MAKKADA P.O. CHUNGATHARA PO NILAMBUR CHELAPPARAM, KAKKODI, KERALA - 679334 CHUNGATHARA PO - 673611 04931 231549/8547531549 KERALA - 679334 0495 2265773(O)/ 2266957(P) 04931 230264 C038 (KANNUR IMMANUEL) C054 (NILAMBUR ST THOMAS) C161 (COYALMANNAM EBENEZER) REV. ABRAHAM CHACKO REV. KURUVILLA PHILIP REV. NOBLE V.JACOB IMMANUEL MAR THOMA CHURCH ST.THOMAS MAR THOMA CHURCH, B.A.J.M. HOSPITAL - V.K.ROAD OLIVEMOUNT, KANNUR SOUTH BAZAR PO NILAMBUR PO COYALMANNAM PO KERALA - 670002 KERALA - 679329 KERALA - 678702 04931-220171 0492 2272037 C173 (MAR THOMA COLLEGE FOR C178 (GUDALUR ST THOMAS) C200 (PAZHANJI IMMANUEL) SPECIAL EDUCATION) REV. SHAJI K.THOMAS REV. GEORGE S. REV. RAJU PHILIP ZACHARIAH ST.THOMAS MAR THOMA CHURCH, IMMANUEL MAR THOMA CHURCH, MARTHOMA COLLEGE FOR SPECIAL - - EDUCATION GUDALUR BAZAAR PO PAZHANJI PO BADIADKA, PERDALA P.O., TAMILNADU - 643212 KERALA - 680542 - 671551 04262 261637(R)/263117(O) 04885 274993 04998 286806/285698(F) C210 (KUNNAMKULAM - MALABAR C256 (UPPADA MISSION COMPLEX) C273 (KATTUKAMPEL CARMEL) DIOCESE) REV. JOHN MATHEW E. REV. JOHN EASOW REV. CHERIAN K.V. DIRECTOR, MALABAR MAR THOMA MAR THOMA MISSIONARY, DIOCESAN SECRETARY, MAR THOMA MISSION COMPLEX,CHUNGATHARA VIA., MUKTI MANDIR, CENTER, UPPADA PO CHAVAKKAD PO, THRISSUR MAKKADA P.O.,CHELAPPRAM, KAKKODI, KERALA - 679334 KERALA - 680506 - 673611 04931-240274 0487-2500296 0495 2265773 C287 (THANIPPADAM SALEM) C297 (MOOKKUTHALA SALEM) C305 (SHARJAH) REV. -

Clergy List Kunnamkulam - Malabar Diocese

CLERGY LIST KUNNAMKULAM - MALABAR DIOCESE PHONE NUMBER / E-Mail Sl No NAME PARISH NEDUVALLOOR CENTRE 1 Rev. Mathew Samuel 04998 286805/286806/285698(R) Mar Thoma College Mar Thoma College of Special Education 9946197386 Badiaduka, Peradale (PO) Kadamana Congregation Kasaragod - 671 551 [email protected] 2 Rev Lijo J George 0490-2412422 Kelakom Immanuel Mar Thoma Church 9447703289 Kelakom P O, Kannur 670 674 [email protected] Neduvaloor Bethel 3 Rev. Binu John 0460-2260220 St.Thomas School Bethel Mar Thoma Church 9846619668 Neduvaloor, Chuzhali (PO), Kannur 670 361 [email protected] Kannur Immanuel 4 Rev Isac P Johnson 0497-2761150 Immanuel M T Church South Bazar P. O, 9990141115 Kannur - 670 002 [email protected] 5 Rev.Febin Mathew Prasad 04602-228328 Arabi Arohanam Arohanam Mar Thoma Church 9847836016 Kolithattu Hermon Arabi P O [email protected] Ulickal (Via), Kannur - 670 705 Cherupuzha Jerusalem, 6 Rev. Reji Easow 0497-2802250 Payannur Bethel Mar Thoma Divya Nikethan 7746973639 Vilayamcodu P O, Pilathara Kannur - 670 504 [email protected] 7 Rev. A. G. Mathew, Rev Rajesh R 04994-280252 (R), 284612 (O) Kasargod St.Thomas Mar Thoma School of Deaf 9447259068, 9746819278 , Parappa Ebenezer Cherkala, Chengala [email protected] Mar Thoma Deaf School Kasragod - 671 541 PHONE NUMBER / E-Mail Sl No NAME PARISH KOZHIKODE CENTRE 8 Rev. Biju K. George 0495 - 2766555 Kozhikode St. Pauls St. Pauls M. T. Church 9446211811 Y M C A Road, Calicut - 673 001 [email protected] 9 Rev. Robin T Mathew 0496 2669449 Chengaroth Immanuel Immanuel M. T. Parsonage 9495372524 Chengaroth P.O, Peruvannamoozhy Anakkulam Sehion Calicut - 673 528 [email protected] 10 Rev. -

List of Teachers Posted from the Following Schools to Various Examination Centers As Assistant Superintendents for Higher Secondary Exam March 2015

LIST OF TEACHERS POSTED FROM THE FOLLOWING SCHOOLS TO VARIOUS EXAMINATION CENTERS AS ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENTS FOR HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM MARCH 2015 08001 - GOVT SMT HSS,CHELAKKARA,THRISSUR 1 DILEEP KUMAR P V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04884231495, 9495222963 2 SWAPNA P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9846374117 3 SHAHINA.K 08035-GOVT. RSR VHSS, VELUR, THRISSUR 04885241085, 9447751409 4 SEENA M 08041-GOVT HSS,PAZHAYANNOOR,THRISSUR 04884254389, 9447674312 5 SEENA P.R 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872356188, 9947088692 6 BINDHU C 08062-ST ANTONY S HSS,PUDUKAD,THRISSUR 04842331819, 9961991555 7 SINDHU K 08137-GOVT. MODEL HSS FOR GIRLS, THRISSUR TOWN, , 9037873800 THRISSUR 8 SREEDEVI.S 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9020409594 9 RADHIKA.R 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742552608, 9847122431 10 VINOD P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9446146634 11 LATHIKADEVI L A 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742482838, 9048923857 12 REJEESH KUMAR.V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04762831245, 9447986101 08002 - GOVT HSS,CHERPU,THRISSUR 1 PREETHY M K 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR 04802820505, 9496288495 2 RADHIKA C S 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR , 9495853650 3 THRESSIA A.O 08005-GOVT HSS,KODAKARA,THRISSUR 04802726280, 9048784499 4 SMITHA M.K 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872317979, 8547619054 5 RADHA M.R 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872342425, 9497180518 6 JANITHA K 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872448686, 9744670871 1 7 SREELEKHA.E.S 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872343515, 9446541276 8 APINDAS T T 08095-ST. PAULS CONVENT EHSS KURIACHIRA, THRISSUR, 04872342644, 9446627146 680006 9 M.JAMILA BEEVI 08107-SN GHSS, KANIMANGALAM, THRISSUR, 680027 , 9388553667 10 MANJULA V R 08118-TECHNICAL HSS, VARADIAM, THRISSUR, 680547 04872216227, 9446417919 11 BETSY C V 08138-GOVT. -

Thrissur Sl.No ULB Scheme Name of the Unit

District: Thrissur Sl.No ULB Scheme Name of the Unit/ Activity Date of start Type- Ind/ Grp 1 Kunnamkulam Own Fund Photostat 2016 Grp 2 Kunnamkulam Own Fund Caterting 2016 Ind 3 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2015 Ind 4 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Tailoring 2014 Ind 5 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Tailoring 2015 Ind 6 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Music Instrument 2014 Ind 7 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2014 Ind 8 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Beauty Parlour 2011 Ind 9 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2015 Ind 10 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2014 Ind 11 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2012 Ind 12 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2012 Ind 13 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2012 Ind 14 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Food Products 2009 Grp 15 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Tailoring 2014 Ind 16 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2014 Ind 17 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Book Binding 2003 Ind 18 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2011 Ind 19 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2012 Ind 20 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2015 Ind 21 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2014 Ind 22 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2012 Ind 23 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2014 Ind 24 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2014 Ind District: Thrissur Sl.No ULB Scheme Name of the Unit/ Activity Date of start Type- Ind/ Grp 25 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Tailoring 2016 Ind 26 Kunnamkulam SJSRY Autorickshaw 2014 Ind 27 Kunnamkulam NULM Santhwanam 2017 Ind 28 Kunnamkulam NULM Kandampully Store 2017 Ind 29 Kunnamkulam NULM Lilly Stores 2017 Ind 30 Kunnamkulam NULM Ethen Fashion Designing 2017 Ind 31 Kunnamkulam NULM Harisree Stores 2017 Ind 32 Kunnamkulam NULM Autorickshaw 2018 Ind 33 -

![Ticf Kkddv KERALA GAZETTE B[Nimcniambn {]Kn≤S∏Spøp∂Xv PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9289/ticf-kkddv-kerala-gazette-b-nimcniambn-kn-s-sp%C3%B8p-xv-published-by-authority-329289.webp)

Ticf Kkddv KERALA GAZETTE B[Nimcniambn {]Kn≤S∏Spøp∂Xv PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY

© Regn. No. KERBIL/2012/45073 tIcf k¿°m¿ dated 5-9-2012 with RNI Government of Kerala Reg. No. KL/TV(N)/634/2015-17 2016 tIcf Kkddv KERALA GAZETTE B[nImcnIambn {]kn≤s∏SpØp∂Xv PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY 2016 Pq¨ 14 Xncph\¥]pcw, hmeyw 5 14th June 2016 \º¿ sNmΔ 1191 CShw 31 31st Idavam 1191 24 Vol. V } Thiruvananthapuram, No. } 1938 tPyjvTw 24 Tuesday 24th Jyaishta 1938 PART IB Notifications and Orders issued by the Kerala Public Service Commission NOTIFICATIONS (2) (1) No. Estt.III(1)35557/03/GW. Thiruvananthapuram, 10th May 2016. No. Estt.III(1)35150/03/GW. Thiruvananthapuram, 10th May 2016. The following is the list of Deputy Secretaries found The following is the list of Joint Secretaries found fit fit by the Departmental Promotion Committee and by the Departmental Promotion Committee and approved approved by the Kerala Public Service Commission for by the Kerala Public Service Commission for promotion to promotion to the post of Joint Secretary/Regional Officer the post of Additional Secretary in the Office of the in the Office of the Kerala Public Service Commission for Kerala Public Service Commission for the year 2016. the year 2016. 1. Sri Ramesh Sarma, P. 1. Smt. Sheela Das 2. Sri Thomas M. Mathew 2. Sri Ganesan, K. 3. Smt. Vijayamma, P. R. 3. Sri Sandeep, N. The above list involves no supersession. The above list involves no supersession. 21 14th JUNE 2016] KERALA GAZETTE 586 (3) NOTIFICATION No. Estt.III(1)35933/03/GW. No. Estt.III(1)36207/03/GW. Thiruvananthapuram, 10th May 2016. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

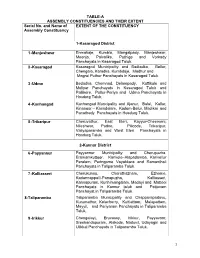

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Mattom Training Report

Report on Farmers’ Training conducted at Mattom on 19-03-2010 Introduction Trichur district is situated in the central part of Kerala, spanning an area of about 3,032 sq km. The district is home to over 10 per cent of Kerala’s population, which is a mix of traditionally rich and the neo-rich. Trichur is known as the cultural capital of Kerala. Plate 1: Map of Trichur district Particulars Details Area 3,032 Sq.Kms Population 29,74,232 Nos. Males 14,22,052 Nos. Females 15,52,180 Nos. Sex ratio : Females/1000 1,092 Density of Population 981 Per Capita Income (in Rs) 21,362 Literacy rate 92.27%; Male 95.11%; Female 89.71% Coastal line in km. 54 Water bodied area in ha. 5,573 Forest area in ha. 103619 Table.1. Demographic and Geographic Particulars of Trichur District The district has a tropical humid climate with an oppressive hot season and plentiful and seasonal rainfall. The hot season from March to May is followed by the South West Monsoon season from June to September. The period from December to February is the North East Monsoon season. However, the rainy season is over by December end and the rest of the period is generally dry and hot. Mattom village belongs to Kandanassery Grama Panchayath of Chowannur Block. It lies 22 kms away from Thrissur. The agrarian economy of Kandanassery Grama Panchayath is characterized by the cultivation of crops like coconut, arecanut and paddy. Among these, coconut is considered as the main crop followed by arecanut and paddy. -

Thalappally Taluk

THALAPPILLY TALUK Kavu Name of Kavu & Custodian Locaon Sy.No. Extent Diety/Pooja GPS Remarks No. Type of Ownership & Address Village (Cents) Details Reading Compound TCR/Tlp Panchayath Wall/ Fence/Pond (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) 1.KANDANASSERY VILLAGE 1 Panthaayil Sarpakavu Chandramathy Thampy Kandaanassery 2.50 Nagaru N 100 CW (Private) Panthaayil House Kandaanassery 1084/3 Bhadrakali 35. 878’ Kandaanassery,Ariyannur Vanadurga E 760 Thriss ‐680102,04885237776 Poojaonceayear 04 .674’ 2 Elathur Sarpakavu Kripavathy Amma Kandaanassery 10.00 Nagaru N 100 CW (Belongs to Elathur Family) Elathur Veedu,Kandaanassery Kandaanassery ‐‐ Once a yaer 36.028’ 04885237716,9447031440 E 760 04.835’ 3 Pallippaa쟼u Sarpakavu P.R.N.Nambeesan Arikanniyur 156/2 1.50 Nagaru N 100 (Belongs to Pallipaa쟼u family) Pallippaa쟼u Veedu, Arikanniyoor Kandaanassery Once a year 36 .65’ Kandaanassery E 760 04. 948’ 4 Nellari Thyvalappil Sarpakavu Rajan. N.S. Kandaanassery 6.00 Mony Nagam N 100 (Family kavu) Nellari Thyvalappil Veedu Kandaanassery ‐‐ Kanni nagam 36.091’ Kandaanassery Brahmarakshas E 760 Thriss – 680102,9496289181 Aayilya 04.801’ 5 Elathur Sarpakavu Rajendran Kandaanassery 1.50 Nagaru N 100 (Family Kavu) Elathur House Kandaanassery ‐‐ Yearly pooja 35.996’ Kandaanassery04885237714 E 760 04.845’ TCR/Tlp Arikanniyoor Sarpakavu A.K. Ramachandran, Arikanniyoor house, E.M.S. Road, Arikanniyoor 107/3 2.50 Maninagam N 100 CW 6 (Private) Arikanniyoor.P.O,9895670343 Kandanasseri Karinagam 36.531’ Seasonal pooja E 760 05.040’ 7 Naduvil Sarpakavu Padmavathy