The Stones of Stenness, Orkney by J N Graham Ritchie with an Account of the Stone of Odin by Ernest W Marwick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus Route X1

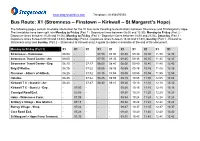

www.stagecoachbus.com Telephone: 01856870555. Bus Route: X1 (Stromness – Finstown – Kirkwall – St Margaret’s Hope) The following pages contain timetable information for the X1 bus route travelling to destinations between Stromness and St Margaret’s Hope. The timetables have been split into Monday to Friday (Part 1 - Departure times between 06:00 and 12:30), Monday to Friday (Part 2 - Departure times between 13:20 and 18:00), Monday to Friday (Part 3 - Departure times between 18:30 and 21:05), Saturday (Part 1 - Departure times between 07:00 and 13:30), Saturday (Part 2 - Departure times between 14:30 and 01:30), Sunday (Part 1 - Kirkwall to Stromness only) and Sunday (Part 2 – Stromness to Kirkwall only) A guide to codes is available at the end of this document. Monday to Friday (Part 1) X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 Stromness - Hamnavoe. 06:00 - - 07:50 08:30 08:40 09:30 10:30 11:30 12:30 Stromness Travel Centre - Arr. 06:05 - - 07:55 08:35 08:45 09:35 10:35 11:35 12:35 Stromness Travel Centre - Dep. 06:10 - 07:17 08:00 08:40 08:50 09:40 10:40 11:40 12:40 Brig O’Waithe. 06:15 - 07:22 08:05 08:45 08:55 09:45 10:45 11:45 12:45 Finstown - Allan’s of Gillock. 06:25 - 07:32 08:15 08:55 09:05 09:55 10:55 11:55 12:55 Hatston. 06:35 - 07:42 08:25 09:05 09:15 10:05 11:05 12:05 13:05 Kirkwall T C - Stand 2 - Arr. -

Pottery Technology As a Revealer of Cultural And

Pottery technology as a revealer of cultural and symbolic shifts: Funerary and ritual practices in the Sion ‘Petit-Chasseur’ megalithic necropolis (3100–1600 BC, Western Switzerland) Eve Derenne, Vincent Ard, Marie Besse To cite this version: Eve Derenne, Vincent Ard, Marie Besse. Pottery technology as a revealer of cultural and symbolic shifts: Funerary and ritual practices in the Sion ‘Petit-Chasseur’ megalithic necropolis (3100–1600 BC, Western Switzerland). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, Elsevier, 2020, 58, pp.101170. 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101170. hal-03051558 HAL Id: hal-03051558 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03051558 Submitted on 10 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 58 (2020) 101170 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Anthropological Archaeology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaa Pottery technology as a revealer of cultural and symbolic shifts: Funerary and ritual practices in the Sion ‘Petit-Chasseur’ megalithic necropolis T (3100–1600 BC, -

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

Service St Margaret's Hope (Ferry Terminal) - Stromness (Hamnavoe) X1 Monday - Friday (Not Bank Holidays)

Service St Margaret's Hope (Ferry Terminal) - Stromness (Hamnavoe) X1 Monday - Friday (not Bank Holidays) Operated by: OC Stagecoach Highlands Timetable valid from 5 Sep 2021 until further notice Service: X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 X1 Notes: XPrd1 Operator: OC OC OC OC OC OC OC OC OC OC OC St Margarets Hope, Ferry terminal Depart: .... .... .... .... .... .... 07:37 .... .... 08:47 09:47 Burray, Shop .... .... .... .... .... .... 07:45 .... .... 08:55 09:55 St Marys, Graeme Park .... .... .... .... .... .... 07:54 .... .... 09:04 10:04 Kirkwall, Hospital Entrance .... .... 06:21 .... .... 07:45 08:05 .... .... 09:15 10:15 Kirkwall, Travel Centre (Stand 2) Arrive: .... .... 06:24 .... .... 07:48 08:08 .... .... 09:18 10:18 Kirkwall, Travel Centre (Stand 2) Depart: 05:05 06:05 06:25 06:55 .... 07:50 .... 08:50 .... 09:20 10:20 Kirkwall, Hatston Bus Garage 05:10 06:10 06:30 07:00 07:10 07:55 .... 08:55 09:00 09:25 10:25 Finstown, Allan's of Gillock 05:20 06:20 06:40 07:10 07:20 08:05 .... 09:05 09:10 09:35 10:35 Stenness, Garage 05:27 06:27 06:47 07:17 07:27 08:12 .... 09:12 09:17 09:42 10:42 Stromness, Travel Centre Arrive: 05:35 .... 06:55 07:25 .... 08:20 .... 09:20 09:30 09:50 10:50 Stromness, Travel Centre Depart: 05:36 .... 06:56 07:26 .... 08:22 .... 09:22 .... 09:52 10:52 Stromness, Hamnavoe Estate Arrive: 05:39 06:35 06:59 07:29 07:35 08:25 ... -

A Pilgrimage to Avebury Stone Circles in Wiltshire

BEST OF BRITAIN A pilgrimage to Avebury stone circles in Wiltshire ere are famous religious pilgrimages, there are also the pilgrimages that one does for oneself. It doesn't have to be on foot or by any particular mode of transport. It is nothing more than the journey of getting to the desired destination, in any way or form. For me, that desired destination was the stone circles of Avebury in Wiltshire, for years I’ve been yearning to sit in stone circles and visit the sacred sites of Europe. So, why visit Avebury, a place that is often sold to us as the poor cousin of the ever-famous Stonehenge? In real - ity, it is not less but much more. Why Avebury? is sacred Neolithic site is the largest set of stone circles out of the thousands in the United Kingdom and in the world. It is older than other sites, although the dating is sketchy. I've heard everything from 2600BC to 4500BC and it’s still up for discussion. Despite being a World Heritage site, Avebury is fully open to the public. Unlike Stonehenge, you can walk in and around the stones. It is accessible by public transport, buses stop in the middle of the village, and the entrance is free. As well as the stone cir - cles, there is also an avenue of stones that take you down to the West Kennet Long Barrow and Silbury Hill. Onsite for a small fee you can visit the museum and manor that are run by the National Trust. -

Concrete Prehistories: the Making of Megalithic Modernism 1901-1939

Concrete Prehistories: The Making of Megalithic Modernism Abstract After water, concrete is the most consumed substance on earth. Every year enough cement is produced to manufacture around six billion cubic metres of concrete1. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern prehistories. We present an archaeology of concrete in the prehistoric landscapes of Stonehenge and Avebury, where concrete is a major component of megalithic sites restored between 1901 and 1964. We explore how concreting changed between 1901 and the Second World War, and the implications of this for constructions of prehistory. We discuss the role of concrete in debates surrounding restoration, analyze the semiotics of concrete equivalents for the megaliths, and investigate the significance of concreting to interpretations of prehistoric building. A technology that mixes ancient and modern, concrete helped build the modern archaeological imagination. Concrete is the substance of the modern –”Talking about concrete means talking about modernity” (Forty 2012:14). It is the material most closely associated with the origins and development of modern architecture, but in the modern era, concrete has also been widely deployed in the preservation and display of heritage. In fact its ubiquity means that concrete can justifiably claim to be the single most dominant substance of heritage conservation practice between 1900 and 1945. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern pasts, and in particular, modern prehistories. As the pre-eminent marker of modernity, concrete was used to separate ancient from modern, but efforts to preserve and display prehistoric megaliths saw concrete and megaliths become entangled. -

Program of the 76Th Annual Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 76 TH ANNUAL MEETING March 30−April 3, 2011 Sacramento, California THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2011 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting 3 Contents 4................ Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5………..….2011 Award Recipients 11.................Maps of the Hyatt Regency Sacramento, Sheraton Grand Sacramento, and the Sacramento Convention Center 17 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 18 ............... General Information . 20. .............. Featured Sessions 22 ............... Summary Schedule 26 ............... A Word about the Sessions 28…………. Student Events 29………..…Sessions At A Glance (NEW!) 37................ Program 169................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 176................ Presidents of SAA . 176................ Annual Meeting Sites 178................ Exhibit Map 179................Exhibitor Directory 190................SAA Committees and Task Forces 194…….…….Index of Participants 4 Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting APRIL 1, 2011 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2010 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

Stinchar Valley Magazine Summer 2018

FREE THE STINCHAR VALLEY Summer MAGAZINE 2018 Climbing Kildonan PRODUCED BY THE COMMUNITIES OF BALLANTRAE, BARR, BARRHILL, COLMONELL, LENDALFOOT, PINWHERRY & PINMORE Supported by Carrick Futures and Hadyard Hill with funding from Scottish Power Renewables and SSE. Mark Hill, Arecleoch and Hadyard Hill Windfarms [email protected] LOCAL AND INTERESTING WEB SITES THE VILLAGES Barr Village http://www.barrvillage.co.uk/ Barrhill www.barrhill.org.uk Ballantrae Village www.ballantrae.org.uk Pinwherry/Pinmore http://www.2pins.org.uk Visit Scotland http://www.visitsouthernscotland.co.uk/ LOCAL INFORMATION AND THINGS TO DO The Stinchar Valley www.stincharvalley.co.uk The Carrick website http://www.carrickayrshire.com Peinn Mor Pottery http://www.peinnmor.co.uk/ Girvan Camera Club http://www.girvancameraclub.org.uk Girvan Attractions http://girvanattractions.co.uk/ Galloway & Ayrshire Biosphere http://www.gsabiosphere.org.uk/ St Colmon Church www.stcolmonparishchurch.org.uk Ballantrae Church www.ballantraeparishchurch.org.uk Dark Sky Park scotland.forestry.gov.uk/forest-parks/galloway-forest-park/dark-skies LOCAL ENVIRONMENT ORGANISATIONS Ayrshire Rivers Trust www.ayrshireriverstrust.org/cisp The Southern Uplands Partnership http://www.sup.org.uk/ Scottish Red Squirrels https://scottishsquirrels.org.uk/ Scottish Natural Heritage http://www.snh.org.uk/ The Woodland Trust http://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk Forestry Commission http://www.forestry.gov.uk/ Scottish Environmental Protection http://www.sepa.org.uk/ USEFUL HELP WEBSITES -

Stonehenge and Avebury WHS Management Plan 2015 Summary

Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site Vision The Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site is universally important for its unique and dense concentration of outstanding prehistoric monuments and sites which together form a landscape without parallel. We will work together to care for and safeguard this special area and provide a tranquil, rural and ecologically diverse setting for it and its archaeology. This will allow present and future generations to explore and enjoy the monuments and their landscape setting more fully. We will also ensure that the special qualities of the World Heritage Site are presented, interpreted and enhanced where appropriate, so that visitors, the local community and the whole world can better understand and value the extraordinary achievements © K020791 Historic England © K020791 Historic of the prehistoric people who left us this rich legacy. Avebury Stone Circle We will realise the cultural, scientific and educational potential of the World Heritage Site as well as its social and economic benefits for the community. © N060499 Historic England © N060499 Historic Stonehenge in summer 2 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 World Heritage Sites © K930754 Historic England © K930754 Historic Arable farming in the WHS below the Ridgeway, Avebury The Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site is internationally important for its complexes of outstanding prehistoric monuments. Stonehenge is the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle in the world, while Avebury is Stonehenge and Avebury were inscribed as a single World Heritage Site in 1986 for their outstanding prehistoric monuments the largest. -

Heart of Neolithic Orkney Map and Guide

World heritage The remarkable monuments that make up the Heart of Neolithic Orkney were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1999. These sites give visitors Heart of a vivid glimpse into the creative genius, lost beliefs and everyday lives of a once flourishing culture. Neolithic World Heritage status places them alongside such globally © Raymond Besant World heritage iconic sites as the Pyramids of Egypt and the Taj Mahal. Sites Orkney site r anger service are listed because they are of importance to all of humanity. The monuments World Heritage Site Orkney’s rich cultural and natural heritage is brought to life R anger Service Ring of Brodgar by the WHS Rangers and team of The evocative Ring of Brodgar is one of the largest and volunteers who support them. best-preserved stone circles in Great Britain. It hints at Throughout the year they run a busy programme of forgotten ritual and belief. public walks, talks and family events for all ages and Skara Brae levels of interest. The village of Skara Brae with its houses and stone Every day at 1pm in June, July and August the Rangers furniture presents an insight into the daily lives of lead walks around the Ring of Brodgar to explore the Neolithic people that is unmatched in northern Europe. iconic monument and its surrounding landscape. There Stones of Stenness are also activities designed specifically for schools and education groups. The Stones of Stenness are the remains of one of the oldest stone circles in the country, raised about 5,000 years ago. The Rangers work closely with the local community to care for the historical landscape and the wildlife that Maeshowe lives in and around its monuments. -

Lochs of Harray and Stenness Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) Are the Two Largest Inland Lochs in Orkney and Are Located in the West Mainland

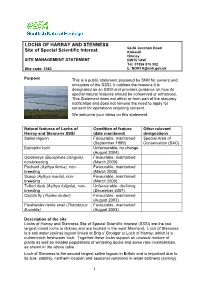

LOCHS OF HARRAY AND STENNESS 54-56 Junction Road Site of Special Scientific Interest Kirkwall Orkney SITE MANAGEMENT STATEMENT KW15 1AW Tel: 01856 875 302 Site code: 1083 E: [email protected] Purpose This is a public statement prepared by SNH for owners and occupiers of the SSSI. It outlines the reasons it is designated as an SSSI and provides guidance on how its special natural features should be conserved or enhanced. This Statement does not affect or form part of the statutory notification and does not remove the need to apply for consent for operations requiring consent. We welcome your views on this statement. Natural features of Lochs of Condition of feature Other relevant Harray and Stenness SSSI (date monitored) designations Saline lagoon Favourable, maintained Special Area of (September 1999) Conservation (SAC) Eutrophic loch Unfavourable, no change (August 2004) Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula), Favourable, maintained non-breeding (March 2000) Pochard (Aythya ferina), non- Favourable, maintained breeding (March 2000) Scaup (Aythya marila), non- Favourable, maintained breeding (March 2000) Tufted duck (Aythya fuligula), non- Unfavourable, declining breeding (December 2007) Caddis fly (Ylodes reuteri) Favourable, maintained (August 2003) Freshwater nerite snail (Theodoxus Favourable, maintained fluviatilis) (August 2003) Description of the site Lochs of Harray and Stenness Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) are the two largest inland lochs in Orkney and are located in the west Mainland. Loch of Stenness is a salt water (saline) lagoon linked at Brig o’ Brodgar to Loch of Harray, which is a nutrient-rich freshwater loch. Together these lochs support an unusual mixture of plants as well as notable populations of wintering ducks and some rare invertebrates, as shown in the above table. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs.