Quaestio Disputata a Response to Karl Becker, S.J., on the Meaning of Subsistit In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

Downside Abbey Press Release

DOWNSIDE ABBEY PRESS RELEASE Tuesday 3rd May 2016 IMMEDIATE RELEASE MINISTRY OF THE PRINTED WORD Scholar-Priests of the Twentieth Century Downside Abbey Press releases a collection of essays exploring the work of eleven priests whose ministry was that of the printed word. Pope St John Paul II reminded all priests of the need for on-going formation, both pastoral and intellectual; his belief was that pastoral activity needed grounding in assiduous study. With an output that spanned the 19th and 20th centuries, the work of the ‘Scholar Priests’ is considered relevant to the Church today. The book explores the work of both religious and secular priests, whose studies ranged across fields as diverse as biblical studies, liturgy, philosophy, history, theology and spirituality, including: Cardinal Gasquet OSB, George Tyrell SJ, Bernard Ward, Adrian Fortescue, John Hungerford Pollen SJ, Herbert Thurston SJ, Ronald Knox, Philip Hughes, David Knowles OSB, Christopher Butler OSB, and Frederick Copleston SJ. “There [is] here indeed a very wide diversity among these scholar priests in the variety of their formation, temperament, career, academic interests and, perhaps more interestingly, in their relations with the Church." Abbot Geoffrey Scott. Edited by Fr John Broadley and Fr Peter Phillips, the book includes contributions by Oliver Rafferty, Stewart Foster, Nicholas Paxton, Thomas McCoog, Dom Aidan Bellenger, Nicholas Schofield, Terry Tastard, Simon Johnson, and Michael Walsh. The book will be released on Thursday 19th May and is available for purchase at www.downside.co.uk priced at £35.00. ----------------PRESS RELEASE ENDS---------------- NOTES TO EDITORS Press contact Claire Wass: [email protected] / 01761 235151 Downside Abbey is a Roman Catholic monastery, and is home to a community of Benedictine monks. -

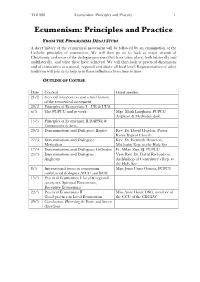

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

Branson-Shaffer-Vatican-II.Pdf

Vatican II: The Radical Shift to Ecumenism Branson Shaffer History Faculty advisor: Kimberly Little The Catholic Church is the world’s oldest, most continuous organization in the world. But it has not lasted so long without changing and adapting to the times. One of the greatest examples of the Catholic Church’s adaptation to the modernization of society is through the Second Vatican Council, held from 11 October 1962 to 8 December 1965. In this gathering of church leaders, the Catholic Church attempted to shift into a new paradigm while still remaining orthodox in faith. It sought to bring the Church, along with the faithful, fully into the twentieth century while looking forward into the twenty-first. Out of the two billion Christians in the world, nearly half of those are Catholic.1 But, Vatican II affected not only the Catholic Church, but Christianity as a whole through the principles of ecumenism and unity. There are many reasons the council was called, both in terms of internal, Catholic needs and also in aiming to promote ecumenism among non-Catholics. There was also an unprecedented event that occurred in the vein of ecumenical beginnings: the invitation of preeminent non-Catholic theologians and leaders to observe the council proceedings. This event, giving outsiders an inside look at 1 World Religions (2005). The Association of Religious Data Archives, accessed 13 April 2014, http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_125.asp. CLA Journal 2 (2014) pp. 62-83 Vatican II 63 _____________________________________________________________ the Catholic Church’s way of meeting modern needs, allowed for more of a reaction from non-Catholics. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI TO BRAZIL ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTH GENERAL CONFERENCE OF THE BISHOPS OF LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN MEETING AND CELEBRATION OF VESPERS WITH THE BISHOPS OF BRAZIL ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS BENEDICT XVI Catedral da Sé, São Paulo Friday, 11 May 2007 Dear Brother Bishops! "Although he was the Son of God, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him." (cf. Heb 5:8-9). 1. The text we have just heard in the Lesson for Vespers contains a profound teaching. Once again we realize that God’s word is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword; it penetrates to the depths of the soul and it grants solace and inspiration to his faithful servants (cf. Heb 4:12). I thank God for the opportunity to be with this distinguished Episcopate, which presides over one of the largest Catholic populations in the world. I greet you with a sense of deep communion and sincere affection, well aware of your devotion to the communities entrusted to your care. The warm reception given to me by the Rector of the Catedral da Sé and by all present has made me feel at home in this great common House which is our Holy Mother, the Catholic Church. 2 I extend a special greeting to the new Officers of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops and, with gratitude for the kind words of its President, Archbishop Geraldo Lyrio Rocha, I offer prayerful good wishes for his work in deepening communion among the Bishops and in promoting common pastoral activity in a territory of continental dimensions. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

The 18Th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists”

“The 18th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists” ................................................................. 2 “Conversion to Interreligious Dialogue.....”, James T. Bretzke, S.J. ................................................. 2 “The Practice of Daoist (Taoist) Compassion”, Michael Saso, S.J. .................................................. 3 “Kehilla, Church and Jewish people”, David Neuhaus, S.J. ............................................................. 6 “Let us Cross Over the Other Shore”, Christophe Ravanel, S.J. ………………………………….….10 “Six Theses on Islam in Europe”, Groupe des Deux Rives……………………………………….11 “Meeting of Jesuits in Islamic Studies, September 2006” .............................................................. 13 “Encounter and the Risk of Change”, Wilfried Dettling, S.J. ......................................................... 14 Secretariat for Interreligious Dialogue; Curia S.J., C.P. 6139, 00195 Roma Prati, Italy; N.11 tel. (39) 06.689.77.567/8; fax: 06.689.77.580; e-mail: [email protected] 2006 4 Vatican II, through the conceptual revolution THE 18TH INTERNATIONAL in ecumenical appreciation produced by CONGRESS OF Unitatis Redintegratio, and into the more JESUIT ECUMENISTS recent involvement of Jesuits in the ecumenical movement since the time of the Second Vatican Council. Edward Farrugia The Jesuit Ecumenists are an informal group looks at a specific issue that lies at the heart of Jesuit scholars active in the movement for of Catholic-Orthodox relations, that of the Christian unity who have -

Page 1 of 13 Experiences of a Council Father 27/09/2012 Http

Experiences of a Council Father Page 1 of 13 Symposium at the Fortieth Anniversary of Vatican II Experiences of a Council Father By Bishop Remi J. De Roo Forty years after the opening of the Second Vatican Council, in retrospect, I would describe that providential event as a prolonged exercise in communal spiritual discernment. While at times perplexing, its ultimate results were definitely positive. It remains for me a superb illustration of how the Holy Spirit continues to guide the Pilgrim People of God throughout the course of history. I consider it the single most impressive experience of my entire life. The focus of Vatican II was pastoral and liturgical as well as theological. Each day began with Eucharist celebrated in a variety of rites. I will never forget how moved I was to see the Gospel solemnly enthroned, a living symbol of the Word of God, present in our midst throughout all the sessions. All the Bishops in communion with Rome were expected to attend. They were joined by an impressive array of major religious superiors, observers from other Churches, theologians, canon lawyers and other scholars, generally known as experts (periti), and a large support staff. The attendance was almost entirely male. Women were not invited until the Third Session and then only as listeners (auditrices). Our entire Church was thus deprived of a very important voice, since the contribution of more than half the membership was muted or heard only indirectly. The Second Vatican Council did not appear suddenly on the horizon, like a cloud in a clear blue sky. -

The Concept of “Sister Churches” in Catholic-Orthodox Relations Since

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Will T. Cohen Washington, D.C. 2010 The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II Will T. Cohen, Ph.D. Director: Paul McPartlan, D.Phil. Closely associated with Catholic-Orthodox rapprochement in the latter half of the 20 th century was the emergence of the expression “sister churches” used in various ways across the confessional division. Patriarch Athenagoras first employed it in this context in a letter in 1962 to Cardinal Bea of the Vatican Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity, and soon it had become standard currency in the bilateral dialogue. Yet today the expression is rarely invoked by Catholic or Orthodox officials in their ecclesial communications. As the Polish Catholic theologian Waclaw Hryniewicz was led to say in 2002, “This term…has now fallen into disgrace.” This dissertation traces the rise and fall of the expression “sister churches” in modern Catholic-Orthodox relations and argues for its rehabilitation as a means by which both Catholic West and Orthodox East may avoid certain ecclesiological imbalances toward which each respectively tends in its separation from the other. Catholics who oppose saying that the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church are sisters, or that the church of Rome is one among several patriarchal sister churches, generally fear that if either of those things were true, the unicity of the Church would be compromised and the Roman primacy rendered ineffective. -

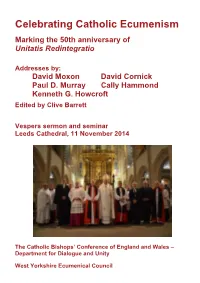

Unitatis Redintegratio

Celebrating Catholic Ecumenism Marking the 50th anniversary of Unitatis Redintegratio Addresses by: David Moxon David Cornick Paul D. Murray Cally Hammond Kenneth G. Howcroft Edited by Clive Barrett Vespers sermon and seminar Leeds Cathedral, 11 November 2014 The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales – Department for Dialogue and Unity West Yorkshire Ecumenical Council 1 Leading figures from Catholic, Anglican and Free Church traditions came together in Leeds on 11th November 2014 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Unitatis Redintegratio, the Decree on Ecumenism that was promulgated by the Second Vatican Council in November 1964. Four hundred people attended a service of Ecumenical Vespers led by the Metropolitan Archbishop of Liverpool, including His Eminence Vincent Nicholls, Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster and the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales. They heard a sermon by the Most Revd. Sir David Moxon, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Representative to the Holy See. (PAGE 3) The service was preceded by a seminar, organised by the Revd Dr Clive Barrett for West Yorkshire Ecumenical Council (WYEC), and chaired by the Rt Revd Tony Robinson, Bishop of Pontefract. Speakers included: the Revd. Dr. David Cornick, General Secretary of Churches Together in England, who put Unitatis Redintegratio into its historical context. (PAGE 9) Professor Paul D. Murray, Professor of Systematic Theology and Dean & Director of the Centre for Catholic Studies, Department of Theology and Religion, Durham University, who spoke of Receptive Ecumenism, the “ecumenism of wounded hands”. (PAGE 15) the Revd. Dr. Cally Hammond, Dean of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge, who stressed the need to trust God's providence in the ecumenical journey. -

Joseph Ratzinger, Student of Thomas

Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology Volume 5, Issue 1 ISSN 2380-7458 Joseph Ratzinger, Student of Thomas Author(s): Jose Isidro Belleza Source: Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology 5, no. 1 (2019): 94-120. Published by: Graduate Theological Union © 2019 Online article published on: August 20, 2019 Copyright Notice: This file and its contents is copyright of the Graduate Theological Union © 2019. All rights reserved. Your use of the Archives of the Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology (BJRT) indicates your acceptance of the BJRT’s policy regarding the use of its resources, as discussed below: Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited with the following exceptions: Ø You may download and print to a local hard disk this entire article for your personal and non- commercial use only. Ø You may quote short sections of this article in other publications with the proper citations and attributions. Ø Permission has been obtained from the Journal’s management for exceptions to redistribution or reproduction. A written and signed letter from the Journal must be secured expressing this permission. To obtain permissions for exceptions, or to contact the Journal regarding any questions regarding any further use of this article, please e-mail the managing editor at [email protected] The Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology aims to offer its scholarly contributions free to the community in furtherance of the Graduate Theological Union’s mission. Joseph Ratzinger, Student of Thomas Jose Isidro Belleza Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology Berkeley, California, U.S.A. -

Hebrews Cambridge University Press C, F

CAMBRIDGE GREEK 'l'ESTAMEN'l' FOR SCHOOLS AND COLLEGES GENERAL EDITOR: R. ST JOHN PARRY, D.D., FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE THE EPISTLE TO THE HEBREWS CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C, F. CLAY, MANAGER LONDON : FETTER LANE, E.C. 4 NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO. BOMBAY 1 CALCUTTA, MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD, MADRAS I TORONTO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TOKYO : MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE EPISTLE TO THE I-IEBREWS Edited by A. NAIRNE, D.D. Fellow and Dean of Jesus College, Cambridge WlTH JN'TRODUCTlON AND NOTES Cambridge at the University Press 1022 l!'irst Edition 1917 Reprinted 192'.l PREFACE BY THE GENERAL EDITOR. THE General Editor does not hold himself respon- sible, except in the most general sense, for the statements, opinions, and interpretations contained in the several volumes of this Series. He believes that the value of the Introduction and the Commentary in each case is largely dependent on the Editor being free as to his treatment of the questions which arise, provided that that treatment is in harmony with the character and scope of the Series. He has therefore contented himself with offering criticisms, urging the ·consideration of alternative interpretations, and the like; and· as a rule he has left the adoption of these suggestions to the discretion of the Editor. The Greek Text adopted in this Series is that of Dr Westcott and Dr Hort with the omission of the marginal readings. For permission to use this Text the thanks of the Syndics of the Cambridge University Press and of the General Editor are due to Messrs Macmillan & Co.