Background Structures and Narrative in Music by Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012.1 Review by David Carson Berry After Allen Forte’s and Steven Gilbert’s Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis was published in 1982, it effectively had the textbook market to itself for a decade (a much older book by Felix Salzer and a new translation of one by Oswald Jonas not withstanding).2 A relatively compact Guide to Schenkerian Analysis, by David Neumeyer and Susan Tepping, was issued in 1992;3 and in 1998 came Allen Cadwallader and David Gagné’s Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach, which is today (in its third edition) the dominant text.4 Despite its ascendance, and the firm legacy of the Forte/Gilbert book, authors continue to crowd what is a comparatively small market within music studies. Steven Porter offered the interesting but dubiously named Schenker Made Simple in 1 Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form, by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012; hardback, $150 (978-0- 415-89214-8), paperback, $68.95 (978-0-415-89215-5); xx, 310 pp. 2 Allen Forte and Steven E. Gilbert, Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis (New York: Norton, 1982). Felix Salzer’s book (Structural Hearing: Tonal Coherence in Music [New York: Charles Boni, 1952]), though popular in its time, was viewed askance by orthodox Schenkerians due to its alterations of core tenets, and it was growing increasingly out of favor with mainstream theorists by the 1980s (as evidenced by the well-known rebuttal of its techniques in Joseph N. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Schenkerian Analysis in the Modern Context of the Musical Analysis

Mathematics and Computers in Biology, Business and Acoustics THE SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS IN THE MODERN CONTEXT OF THE MUSICAL ANALYSIS ANCA PREDA, PETRUTA-MARIA COROIU Faculty of Music Transilvania University of Brasov 9 Eroilor Blvd ROMANIA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: - Music analysis represents the most useful way of exploration and innovation of musical interpretations. Performers who use music analysis efficiently will find it a valuable method for finding the kind of musical richness they desire in their interpretations. The use of Schenkerian analysis in performance offers a rational basis and an unique way of interpreting music in performance. Key-Words: - Schenkerian analysis, structural hearing, prolongation, progression,modernity. 1 Introduction Even in a simple piece of piano music, the ear Musical analysis is a musicological approach in hears a vast number of notes, many of them played order to determine the structural components of a simultaneously. The situation is similar to that found musical text, the technical development of the in language. Although music is quite different to discourse, the morphological descriptions and the spoken language, most listeners will still group the understanding of the meaning of the work. Analysis different sounds they hear into motifs, phrases and has complete autonomy in the context of the even longer sections. musicological disciplines as the music philosophy, Schenker was not afraid to criticize what he saw the musical aesthetics, the compositional technique, as a general lack of theoretical and practical the music history and the musical criticism. understanding amongst musicians. As a dedicated performer, composer, teacher and editor of music himself, he believed that the professional practice of 2 Problem Formulation all these activities suffered from serious misunderstandings of how tonal music works. -

Unified Music Theories for General Equal-Temperament Systems

Unified Music Theories for General Equal-Temperament Systems Brandon Tingyeh Wu Research Assistant, Research Center for Information Technology Innovation, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan ABSTRACT Why are white and black piano keys in an octave arranged as they are today? This article examines the relations between abstract algebra and key signature, scales, degrees, and keyboard configurations in general equal-temperament systems. Without confining the study to the twelve-tone equal-temperament (12-TET) system, we propose a set of basic axioms based on musical observations. The axioms may lead to scales that are reasonable both mathematically and musically in any equal- temperament system. We reexamine the mathematical understandings and interpretations of ideas in classical music theory, such as the circle of fifths, enharmonic equivalent, degrees such as the dominant and the subdominant, and the leading tone, and endow them with meaning outside of the 12-TET system. In the process of deriving scales, we create various kinds of sequences to describe facts in music theory, and we name these sequences systematically and unambiguously with the aim to facilitate future research. - 1 - 1. INTRODUCTION Keyboard configuration and combinatorics The concept of key signatures is based on keyboard-like instruments, such as the piano. If all twelve keys in an octave were white, accidentals and key signatures would be meaningless. Therefore, the arrangement of black and white keys is of crucial importance, and keyboard configuration directly affects scales, degrees, key signatures, and even music theory. To debate the key configuration of the twelve- tone equal-temperament (12-TET) system is of little value because the piano keyboard arrangement is considered the foundation of almost all classical music theories. -

An Exploration of the Relationship Between Mathematics and Music

An Exploration of the Relationship between Mathematics and Music Shah, Saloni 2010 MIMS EPrint: 2010.103 Manchester Institute for Mathematical Sciences School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Reports available from: http://eprints.maths.manchester.ac.uk/ And by contacting: The MIMS Secretary School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Manchester, M13 9PL, UK ISSN 1749-9097 An Exploration of ! Relation"ip Between Ma#ematics and Music MATH30000, 3rd Year Project Saloni Shah, ID 7177223 University of Manchester May 2010 Project Supervisor: Professor Roger Plymen ! 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface! 3 1.0 Music and Mathematics: An Introduction to their Relationship! 6 2.0 Historical Connections Between Mathematics and Music! 9 2.1 Music Theorists and Mathematicians: Are they one in the same?! 9 2.2 Why are mathematicians so fascinated by music theory?! 15 3.0 The Mathematics of Music! 19 3.1 Pythagoras and the Theory of Music Intervals! 19 3.2 The Move Away From Pythagorean Scales! 29 3.3 Rameau Adds to the Discovery of Pythagoras! 32 3.4 Music and Fibonacci! 36 3.5 Circle of Fifths! 42 4.0 Messiaen: The Mathematics of his Musical Language! 45 4.1 Modes of Limited Transposition! 51 4.2 Non-retrogradable Rhythms! 58 5.0 Religious Symbolism and Mathematics in Music! 64 5.1 Numbers are God"s Tools! 65 5.2 Religious Symbolism and Numbers in Bach"s Music! 67 5.3 Messiaen"s Use of Mathematical Ideas to Convey Religious Ones! 73 6.0 Musical Mathematics: The Artistic Aspect of Mathematics! 76 6.1 Mathematics as Art! 78 6.2 Mathematical Periods! 81 6.3 Mathematics Periods vs. -

Program and Abstracts for 2005 Meeting

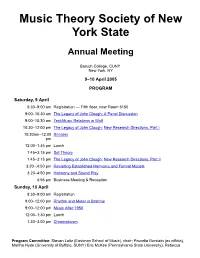

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting Baruch College, CUNY New York, NY 9–10 April 2005 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration — Fifth floor, near Room 5150 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion 9:00–10:30 am TextMusic Relations in Wolf 10:30–12:00 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part I 10:30am–12:00 Scriabin pm 12:00–1:45 pm Lunch 1:45–3:15 pm Set Theory 1:45–3:15 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part II 3:20–;4:50 pm Revisiting Established Harmonic and Formal Models 3:20–4:50 pm Harmony and Sound Play 4:55 pm Business Meeting & Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration 9:00–12:00 pm Rhythm and Meter in Brahms 9:00–12:00 pm Music After 1950 12:00–1:30 pm Lunch 1:30–3:00 pm Chromaticism Program Committee: Steven Laitz (Eastman School of Music), chair; Poundie Burstein (ex officio), Martha Hyde (University of Buffalo, SUNY) Eric McKee (Pennsylvania State University); Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), and Alexandra Vojcic (Juilliard). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion Chair: Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) Jack Douthett (University at Buffalo, SUNY) Nora Engebretsen (Bowling Green State University) Jonathan Kochavi (Swarthmore, PA) Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) John Clough was a pioneer in the field of scale theory. -

CIRCLE of FIFTHS WORKSHOP a Useful Concept for When You Want to Jam with Other Instruments Or Write a Song!

CIRCLE OF FIFTHS WORKSHOP A useful concept for when you want to jam with other instruments or write a song! The Circle of Fifths shows the relationships among the twelve tones of the Chromatic Scale, their corresponding key signatures and the associated Major and Minor keys. The word "chromatic" comes from the Greek word chroma meaning "color." The chromatic scale consists of 12 notes each a half step or “semi-tone” apart. It is from the chromatic scale that every other scale or chord in most Western music is derived. Here’s the C chromatic scale going up as an example: C C# D D# E F F# G G# A A# B C In everyday terms: The Circle of Fifths is useful if you’re playing in an open jam with other instruments, e.g., guitars or fiddles around a campfire, or when you’re trying to figure out the chords of a song from scratch, or write your own song. The Circle of Fifths is a music theory picture. Each “segment” on the circle represents a note, a chord, and a key. Why is it called the Circle of Fifths? When going clockwise, each key is a fifth above the last. When going counter-clockwise, each key is a fourth above the last, so you may also hear it called the “circle of fourths”. The perfect fifth interval is said to be consonant, meaning it is a typical “pleasant sound” and sounds stable within music (the groundwork for this concept was set by Pythagoras and based on the sound frequency ratios). -

Analyzing Fugue: a Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick

Analyzing Fugue: A Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick. Harmonologia Series No. 8 (edited by Joel Lester). Stuyvesant, New York: Pendragon Press, 1995. Review by Robert Gauldin In recent years focus has tended to shift from Heinrich Schenker's canonical principles of hierarchical voice leading to his comments on musical form, as formulated in the final section of Der freie Satz.1 While Schenker's middleground and background levels are eminently suited for revealing the tonal structure of such designs as ternary and sonata, their application to other formal genres raises certain questions.2 Aside from his essay on organicism in the fugue, which deals with the C Minor fugue in WTC I, Schenker rarely ventured into contrapuntal genres.3 In fact, only a handful of fugal analyses exist in subsequent Schenkerian literature.4 It is ^See his Free Composition. 2 vols. Translated and edited by Ernst Oster. (New York: Longman, 1979), 1:128-45. ^In this regard, Joel Garland and Charles Smith have recently explored spe- cific aspects of rondo and variation form, respectively. See Garland's "Form, Genre, and Style in the Eighteenth-Century Rondo," Music Theory Spectrum 17/1 (Spring 1995), 27-52, and Smith's "Head-Tones, Mediants, Reprises: A Formal Narrative of Brahms' Handel Variations," paper deliv- ered at the Eastman School of Music, March 1995. In the latter, interest centers around^ Variation 21, where the original Urlinie 3-2-1 in Bb major is now set as 5-4-3 in the relative minor key. A similar problem of Urlinie reinterpretation occurs in Brahms' Haydn Variations Op. -

The Piano Improvisations of Chick Corea: an Analytical Study

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 The iP ano Improvisations of Chick Corea: An Analytical Study. Daniel Alan Duke Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Duke, Daniel Alan, "The iP ano Improvisations of Chick Corea: An Analytical Study." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6334. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6334 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the te d directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The University of Chicago an Experience-Oriented

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AN EXPERIENCE-ORIENTED APPROACH TO ANALYZING STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY SARAH MARIE IKER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 CONTENTS List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... ix Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. x Introduction: Analysis, Experience, and Experience-Oriented Analysis ..................................... 1 1 Neoclassicism, Analysis, and Experience ................................................................................ 10 1.1 Neoclassicism After the Great War ................................................................................. 10 1.2 Analyzing Neoclassicism: Problems and Solutions ....................................................... 18 1.3 Whence Listener Experience? ........................................................................................... 37 1.4 The Problem of Historicism ............................................................................................ -

A Schenkerian Analysis of Ravel's Introduction And

Schenkerian Analysis of Ravel A SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS OF RAVEL’S INTRODUCTION AND ALLEGRO FROM THE BONNY METHOD OF GUIDED IMAGERY AND MUSIC Robert Gross, MM, MA, DMA ABSTRACT This study gathers image and emotional responses reported by Bruscia et al. (2005) to Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro, which is a work included for use in the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (BMGIM). A Schenkerian background of the Ravel is created using the emotional and image responses reported by Bruscia’s team. This background is then developed further into a full middleground Schenkerian analysis of the Ravel, which is then annotated. Each annotation observes some mechanical phenomenon which is then correlated to one or more of the responses given by Bruscia’s team. The argument is made that Schenkerian analysis can inform clinicians about the potency of the pieces they use in BMGIM, and can explain seemingly contradictory or incongruous responses given by clients who experience BMGIM. The study includes a primer on the basics of Schenkerian analysis and a discussion of implications for clinical practice. INTRODUCTION For years I had been fascinated by musical analysis. My interest began in a graduate-level class at Rice University in 1998 taught by Dr. Richard Lavenda, who, regarding our final project, had the imagination to say that we could use an analytical method of our devising. I invented a very naïve method of performing Schenkerian analysis on post-tonal music; the concept of post-tonal prolongation and the application of Schenkerian principles to post-tonal music became a preoccupation that has persisted for me to this day. -

Consonance & Dissonance

UIUC Physics 406 Acoustical Physics of Music Consonance & Dissonance: Consonance: A combination of two (or more) tones of different frequencies that results in a musically pleasing sound. Why??? Dissonance: A combination of two (or more) tones of different frequencies that results in a musically displeasing sound. Why??? n.b. Perception of sounds is also wired into (different of) our emotional centers!!! Why???/How did this happen??? The Greek scholar Pythagoras discovered & studied the phenomenon of consonance & dissonance, using an instrument called a monochord (see below) – a simple 1-stringed instrument with a movable bridge, dividing the string of length L into two segments, x and L–x. Thus, the two string segments can have any desired ratio, R x/(L–x). (movable) L x x L When the monochord is played, both string segments vibrate simultaneously. Since the two segments of the string have a common tension, T, and the mass per unit length, = M/L is the same on both sides of the string, then the speed of propagation of waves on each of the two segments of the string is the same, v = T/, and therefore on the x-segment of string, the wavelength (of the fundamental) is x = 2x = v/fx and on the (L–x) segment of the string, we have Lx = 2(L–x) = v/fLx. Thus, the two frequencies associated with the two vibrating string segments x and L – x on either side of the movable bridge are: v f x 2x v f Lx 2L x - 1 - Professor Steven Errede, Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois 2002 - 2017.