Unified Music Theories for General Equal-Temperament Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Adaptive Tuning System for MIDI Pianos

David Løberg Code Groven.Max: School of Music Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, MI 49008 USA An Adaptive Tuning [email protected] System for MIDI Pianos Groven.Max is a real-time program for mapping a renstemningsautomat, an electronic interface be- performance on a standard keyboard instrument to tween the manual and the pipes with a kind of arti- a nonstandard dynamic tuning system. It was origi- ficial intelligence that automatically adjusts the nally conceived for use with acoustic MIDI pianos, tuning dynamically during performance. This fea- but it is applicable to any tunable instrument that ture overcomes the historic limitation of the stan- accepts MIDI input. Written as a patch in the MIDI dard piano keyboard by allowing free modulation programming environment Max (available from while still preserving just-tuned intervals in www.cycling74.com), the adaptive tuning logic is all keys. modeled after a system developed by Norwegian Keyboard tunings are compromises arising from composer Eivind Groven as part of a series of just the intersection of multiple—sometimes oppos- intonation keyboard instruments begun in the ing—influences: acoustic ideals, harmonic flexibil- 1930s (Groven 1968). The patch was first used as ity, and physical constraints (to name but three). part of the Groven Piano, a digital network of Ya- Using a standard twelve-key piano keyboard, the maha Disklavier pianos, which premiered in Oslo, historical problem has been that any fixed tuning Norway, as part of the Groven Centennial in 2001 in just intonation (i.e., with acoustically pure tri- (see Figure 1). The present version of Groven.Max ads) will be limited to essentially one key. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

3 Manual Microtonal Organ Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013

3 Manual Microtonal Organ http://www.bek.no/~ruben/Research/Downloads/software.html Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013 An interface to existing software A motivation for creating this instrument has been an interest for gaining experience with a large range of intonation systems. This software instrument is built with Max 61, as an interface to the Fluidsynth object2. Fluidsynth offers possibilities for retuning soundfont banks (Sf2 format) to 12-tone or full-register tunings. Max 6 introduced the dictionary format, which has been useful for creating a tuning database in text format, as well as storing presets. This tuning database can naturally be expanded by users, if tunings are written in the syntax read by this instrument. The freely available Jeux organ soundfont3 has been used as a default soundfont, while any instrument in the sf2 format can be loaded. The organ interface The organ window 3 MIDI Keyboards This instrument contains 3 separate fluidsynth modules, named Manual 1-3. 3 keysliders can be played staccato by the mouse for testing, while the most musically sufficient option is performing from connected MIDI keyboards. Available inputs will be automatically recognized and can be selected from the menus. To keep some of the manuals silent, select the bottom alternative "to 2ManualMicroORGANircamSpat 1", which will not receive MIDI signal, unless another program (for instance Sibelius) is sending them. A separate menu can be used to select a foot trigger. The red toggle must be pressed for this to be active. This has been tested with Behringer FCB1010 triggers. Other devices could possibly require adjustments to the patch. -

The Group-Theoretic Description of Musical Pitch Systems

The Group-theoretic Description of Musical Pitch Systems Marcus Pearce [email protected] 1 Introduction Balzano (1980, 1982, 1986a,b) addresses the question of finding an appropriate level for describing the resources of a pitch system (e.g., the 12-fold or some microtonal division of the octave). His motivation for doing so is twofold: “On the one hand, I am interested as a psychologist who is not overly impressed with the progress we have made since Helmholtz in understanding music perception. On the other hand, I am interested as a computer musician who is trying to find ways of using our pow- erful computational tools to extend the musical [domain] of pitch . ” (Balzano, 1986b, p. 297) Since the resources of a pitch system ultimately depend on the pairwise relations between pitches, the question is one of how to conceive of pitch intervals. In contrast to the prevailing approach which de- scribes intervals in terms of frequency ratios, Balzano presents a description of pitch sets as mathematical groups and describes how the resources of any pitch system may be assessed using this description. Thus he is concerned with presenting an algebraic description of pitch systems as a competitive alternative to the existing acoustic description. In these notes, I shall first give a brief description of the ratio based approach (§2) followed by an equally brief exposition of some necessary concepts from the theory of groups (§3). The following three sections concern the description of the 12-fold division of the octave as a group: §4 presents the nature of the group C12; §5 describes three perceptually relevant properties of pitch-sets in C12; and §6 describes three musically relevant isomorphic representations of C12. -

Perceptual Interactions of Pitch and Timbre: an Experimental Study on Pitch-Interval Recognition with Analytical Applications

Perceptual interactions of pitch and timbre: An experimental study on pitch-interval recognition with analytical applications SARAH GATES Music Theory Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University Montréal • Quebec • Canada August 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. Copyright © 2015 • Sarah Gates Contents List of Figures v List of Tables vi List of Examples vii Abstract ix Résumé xi Acknowledgements xiii Author Contributions xiv Introduction 1 Pitch, Timbre and their Interaction • Klangfarbenmelodie • Goals of the Current Project 1 Literature Review 7 Pitch-Timbre Interactions • Unanswered Questions • Resulting Goals and Hypotheses • Pitch-Interval Recognition 2 Experimental Investigation 19 2.1 Aims and Hypotheses of Current Experiment 19 2.2 Experiment 1: Timbre Selection on the Basis of Dissimilarity 20 A. Rationale 20 B. Methods 21 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure C. Results 23 2.3 Experiment 2: Interval Identification 26 A. Rationale 26 i B. Method 26 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure • Evaluation of Trials • Speech Errors and Evaluation Method C. Results 37 Accuracy • Response Time D. Discussion 51 2.4 Conclusions and Future Directions 55 3 Theoretical Investigation 58 3.1 Introduction 58 3.2 Auditory Scene Analysis 59 3.3 Carter Duets and Klangfarbenmelodie 62 Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux • Carter and Klangfarbenmelodie: Examples with Timbral Dissimilarity • Conclusions about Carter 3.4 Webern and Klangfarbenmelodie in Quartet op. 22 and Concerto op 24 83 Quartet op. 22 • Klangfarbenmelodie in Webern’s Concerto op. 24, mvt II: Timbre’s effect on Motivic and Formal Boundaries 3.5 Closing Remarks 110 4 Conclusions and Future Directions 112 Appendix 117 A.1,3,5,7,9,11,13 Confusion Matrices for each Timbre Pair A.2,4,6,8,10,12,14 Confusion Matrices by Direction for each Timbre Pair B.1 Response Times for Unisons by Timbre Pair References 122 ii List of Figures Fig. -

MTO 19.3: Nobile, Interval Permutations

Volume 19, Number 3, September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory Interval Permutations Drew F. Nobile NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.3/mto.13.19.3.nobile.php KEYWORDS: Interval permutations, intervals, post-tonal analysis, mathematical modeling, set-class, space, Schoenberg, The Book of the Hanging Gardens ABSTRACT: This paper presents a framework for analyzing the interval structure of pitch-class segments (ordered pitch-class sets). An “interval permutation” is a reordering of the intervals that arise between adjacent members of these pitch-class segments. Because pitch-class segments related by interval permutation are not necessarily members of the same set-class, this theory has the capability to demonstrate aurally significant relationships between sets that are not related by transposition or inversion. I begin with a theoretical investigation of interval permutations followed by a discussion of the relationship of interval permutations to traditional pitch-class set theory, specifically focusing on how various set-classes may be related by interval permutation. A final section applies these theories to analyses of several songs from Schoenberg’s op. 15 song cycle The Book of the Hanging Gardens. Received May 2013 [1] Example 1 shows the score to the opening measures of “Sprich nicht immer von dem Laub,” the fourteenth song from Schoenberg’s Book of the Hanging Gardens, op. 15. Upon first listen, one is drawn to the relationship between the piano’s gesture in the first measure and the vocal line in the second. -

Nora-Louise Müller the Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet An

Nora-Louise Müller The Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet An Introduction to Acoustics and Playing Technique The Bohlen-Pierce scale was discovered in the 1970s and 1980s by Heinz Bohlen and John R. Pierce respectively. Due to a lack of instruments which were able to play the scale, hardly any compositions in Bohlen-Pierce could be found in the past. Just a few composers who work in electronic music used the scale – until the Canadian woodwind maker Stephen Fox created a Bohlen-Pierce clarinet, instigated by Georg Hajdu, professor of multimedia composition at Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg. Hence the number of Bohlen- Pierce compositions using the new instrument is increasing constantly. This article gives a short introduction to the characteristics of the Bohlen-Pierce scale and an overview about Bohlen-Pierce clarinets and their playing technique. The Bohlen-Pierce scale Unlike the scales of most tone systems, it is not the octave that forms the repeating frame of the Bohlen-Pierce scale, but the perfect twelfth (octave plus fifth), dividing it into 13 steps, according to various mathematical considerations. The result is an alternative harmonic system that opens new possibilities to contemporary and future music. Acoustically speaking, the octave's frequency ratio 1:2 is replaced by the ratio 1:3 in the Bohlen-Pierce scale, making the perfect twelfth an analogy to the octave. This interval is defined as the point of reference to which the scale aligns. The perfect twelfth, or as Pierce named it, the tritave (due to the 1:3 ratio) is achieved with 13 tone steps. -

Reconsidering Pitch Centricity Stanley V

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 2011 Reconsidering Pitch Centricity Stanley V. Kleppinger University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Commons Kleppinger, Stanley V., "Reconsidering Pitch Centricity" (2011). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 63. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/63 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Reconsidering Pitch Centricity STANLEY V. KLEPPINGER Analysts commonly describe the musical focus upon a particular pitch class above all others as pitch centricity. But this seemingly simple concept is complicated by a range of factors. First, pitch centricity can be understood variously as a compositional feature, a perceptual effect arising from specific analytical or listening strategies, or some complex combination thereof. Second, the relation of pitch centricity to the theoretical construct of tonality (in any of its myriad conceptions) is often not consistently or robustly theorized. Finally, various musical contexts manifest or evoke pitch centricity in seemingly countless ways and to differing degrees. This essay examines a range of compositions by Ligeti, Carter, Copland, Bartok, and others to arrive at a more nuanced perspective of pitch centricity - one that takes fuller account of its perceptual foundations, recognizes its many forms and intensities, and addresses its significance to global tonal structure in a given composition. -

An Exploration of the Relationship Between Mathematics and Music

An Exploration of the Relationship between Mathematics and Music Shah, Saloni 2010 MIMS EPrint: 2010.103 Manchester Institute for Mathematical Sciences School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Reports available from: http://eprints.maths.manchester.ac.uk/ And by contacting: The MIMS Secretary School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Manchester, M13 9PL, UK ISSN 1749-9097 An Exploration of ! Relation"ip Between Ma#ematics and Music MATH30000, 3rd Year Project Saloni Shah, ID 7177223 University of Manchester May 2010 Project Supervisor: Professor Roger Plymen ! 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface! 3 1.0 Music and Mathematics: An Introduction to their Relationship! 6 2.0 Historical Connections Between Mathematics and Music! 9 2.1 Music Theorists and Mathematicians: Are they one in the same?! 9 2.2 Why are mathematicians so fascinated by music theory?! 15 3.0 The Mathematics of Music! 19 3.1 Pythagoras and the Theory of Music Intervals! 19 3.2 The Move Away From Pythagorean Scales! 29 3.3 Rameau Adds to the Discovery of Pythagoras! 32 3.4 Music and Fibonacci! 36 3.5 Circle of Fifths! 42 4.0 Messiaen: The Mathematics of his Musical Language! 45 4.1 Modes of Limited Transposition! 51 4.2 Non-retrogradable Rhythms! 58 5.0 Religious Symbolism and Mathematics in Music! 64 5.1 Numbers are God"s Tools! 65 5.2 Religious Symbolism and Numbers in Bach"s Music! 67 5.3 Messiaen"s Use of Mathematical Ideas to Convey Religious Ones! 73 6.0 Musical Mathematics: The Artistic Aspect of Mathematics! 76 6.1 Mathematics as Art! 78 6.2 Mathematical Periods! 81 6.3 Mathematics Periods vs. -

Mto.99.5.2.Soderberg

Volume 5, Number 2, March 1999 Copyright © 1999 Society for Music Theory Stephen Soderberg REFERENCE: MTO Vol. 4, No. 3 KEYWORDS: John Clough, Jack Douthett, David Lewin, maximally even set, microtonal music, hyperdiatonic system, Riemann system ABSTRACT: This article is a continuation of White Note Fantasy, Part I, published in MTO Vol. 4, No. 3 (May 1998). Part II combines some of the work done by others on three fundamental aspects of diatonic systems: underlying scale structure, harmonic structure, and basic voice leading. This synthesis allows the recognition of select hyperdiatonic systems which, while lacking some of the simple and direct character of the usual (“historical”) diatonic system, possess a richness and complexity which have yet to be fully exploited. II. A Few Hypertonal Variations 5. Necklaces 6. The usual diatonic as a model for an abstract diatonic system 7. An abstract diatonic system 8. Riemann non-diatonic systems 9. Extension of David Lewin’s Riemann systems References 5. Necklaces [5.1] Consider a symmetric interval string of cardinality n = c+d which contains c interval i’s and d interval j’s. If the i’s and j’s in such a string are additionally spaced as evenly apart from one another as possible, we will call this string a “necklace.” If s is a string in Cn and p is an element of Cn, then the structure ps is a “necklace set.” Thus <iijiij>, <ijijij>, and <ijjijjjijjj> are necklaces, but <iijjii>, <jiijiij>, and <iijj>, while symmetric, are not necklaces. i and j may also be equal, so strings of the 1 of 18 form <iii...> are valid necklaces. -

Program and Abstracts for 2005 Meeting

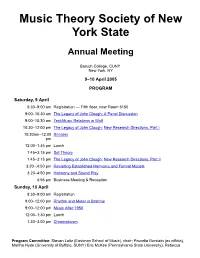

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting Baruch College, CUNY New York, NY 9–10 April 2005 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration — Fifth floor, near Room 5150 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion 9:00–10:30 am TextMusic Relations in Wolf 10:30–12:00 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part I 10:30am–12:00 Scriabin pm 12:00–1:45 pm Lunch 1:45–3:15 pm Set Theory 1:45–3:15 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part II 3:20–;4:50 pm Revisiting Established Harmonic and Formal Models 3:20–4:50 pm Harmony and Sound Play 4:55 pm Business Meeting & Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration 9:00–12:00 pm Rhythm and Meter in Brahms 9:00–12:00 pm Music After 1950 12:00–1:30 pm Lunch 1:30–3:00 pm Chromaticism Program Committee: Steven Laitz (Eastman School of Music), chair; Poundie Burstein (ex officio), Martha Hyde (University of Buffalo, SUNY) Eric McKee (Pennsylvania State University); Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), and Alexandra Vojcic (Juilliard). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion Chair: Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) Jack Douthett (University at Buffalo, SUNY) Nora Engebretsen (Bowling Green State University) Jonathan Kochavi (Swarthmore, PA) Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) John Clough was a pioneer in the field of scale theory. -

Microtonality As an Expressive Device: an Approach for the Contemporary Saxophonist

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Dissertations Conservatory of Music and Drama 2009 Microtonality as an Expressive Device: an Approach for the Contemporary Saxophonist Seán Mac Erlaine Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaconmusdiss Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Mac Erlaine, S.: Microtonality as an Expressive Device: an Approach for the Contemporary Saxophonist. Masters Dissertation. Technological University Dublin, 2009. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Conservatory of Music and Drama at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Microtonality as an expressive device: An approach for the contemporary saxophonist September 2009 Seán Mac Erlaine www.sean-og.com Table of Contents Abstract i Introduction ii CHAPTER ONE 1 1.1 Tuning Theory 1 1.1.1 Tuning Discrepancies 1 1.2 Temperament for Keyboard Instruments 2 1.3 Non‐fixed Intonation Instruments 5 1.4 Dominance of Equal Temperament 7 1.5 The Evolution of Equal Temperament: Microtonality 9 CHAPTER TWO 11 2.1 Twentieth Century Tradition of Microtonality 11 2.2 Use of Microtonality