A Historical and Phonetic Study of Negro Dialect. T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, ,Mter Mitwirkung Von Theodor \\'1

alter SELECTED WRITINGS VOLUME 1 1913-1926 Edited by Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England , . I Contents Copyright © 1996 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights rese rved Printed in the United States of America y l Second printing, 1997 METAPHYSICS OF "Experience" 3 This work is a transla tion of selec tions from Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, ,mter Mitwirkung von Theodor \\'1. Adorno und Gershom Sch olem, heraltSgegeben von Rolf Tiedemann lind Hermann The Metaphysics of You Schweppenhiiuser, copyright © 1972, 1974, 1977, 1982, 1985, 1989 by Suh rkamp Verlag. "The Task of rhe Tra nslator" originally appeared in English in Wal ter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed ited by Hannah Two Poems by Friedrich Are nd t, English translation copyright © 1968 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. "On Language as Such The Life of Students 3' and the Language of Man," "Fate and Cha racter," "Critique of Violen,?;" " Nap les," and "One-Way Street" originally appeared in English in Walter Benjamin, Reflections, English translation copyright Aphorisms on Imaginati © 1978 by Harcoun Brace Jovanovich, Inc . Published by arrangement with Harc ourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. "One-Way Street" also appeared i.n Walter Benjamin, "One-Way Street " and Other Writings (Lon A Child's View of ColOl don: NLBNerso, 1979, 1985). "Socrates" and "On the Program of the Coming Philosophy" originally appeared in English in The Philosophical Forum 15, nos. 1-2 (1983-1984). Socrates 52 Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from Inter Nationes, Bonn. -

11 — 27 August 2018 See P91—137 — See Children’S Programme Gifford Baillie Thanks to All Our Sponsors and Supporters

FREEDOM. 11 — 27 August 2018 Baillie Gifford Programme Children’s — See p91—137 Thanks to all our Sponsors and Supporters Funders Benefactors James & Morag Anderson Jane Attias Geoff & Mary Ball The BEST Trust Binks Trust Lel & Robin Blair Sir Ewan & Lady Brown Lead Sponsor Major Supporter Richard & Catherine Burns Gavin & Kate Gemmell Murray & Carol Grigor Eimear Keenan Richard & Sara Kimberlin Archie McBroom Aitken Professor Alexander & Dr Elizabeth McCall Smith Anne McFarlane Investment managers Ian Rankin & Miranda Harvey Lady Susan Rice Lord Ross Fiona & Ian Russell Major Sponsors The Thomas Family Claire & Mark Urquhart William Zachs & Martin Adam And all those who wish to remain anonymous SINCE Scottish Mortgage Investment Folio Patrons 909 1 Trust PLC Jane & Bernard Nelson Brenda Rennie And all those who wish to remain anonymous Trusts The AEB Charitable Trust Barcapel Foundation Binks Trust The Booker Prize Foundation Sponsors The Castansa Trust John S Cohen Foundation The Crerar Hotels Trust Cruden Foundation The Educational Institute of Scotland The Ettrick Charitable Trust The Hugh Fraser Foundation The Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund Margaret Murdoch Charitable Trust New Park Educational Trust Russell Trust The Ryvoan Trust The Turtleton Charitable Trust With thanks The Edinburgh International Book Festival is sited in Charlotte Square Gardens by the kind permission of the Charlotte Square Proprietors. Media Sponsors We would like to thank the publishers who help to make the Festival possible, Essential Edinburgh for their help with our George Street venues, the Friends and Patrons of the Edinburgh International Book Festival and all the Supporters other individuals who have donated to the Book Festival this year. -

TITLE Kansas State Capitol Guide for Young People. Curriculum Packet for Teachers of Grades 4-7. INSTITUTION Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka.; Kansas State Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 477 746 SO 034 927 TITLE Kansas State Capitol Guide for Young People. Curriculum Packet for Teachers of Grades 4-7. INSTITUTION Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka.; Kansas State Dept. of Education, Topeka. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 27p.; Prepared by the Education and Outreach Division. Intended to supplement the "Kansas State Capitol Guide for Young People." AVAILABLE FROM Kansas State Historical Society, 6425 S.W. 6th Avenue, Topeka, KS 66615. Tel: 785-272-8681; Fax: 785-272-8682; Web site: http://www.kshs.org/. For full text: http://www.kshs.org/teachers/ classroom/capitolguide.htm. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Education; Guides; *Historic Sites; *Social Studies; *State Government; *State History IDENTIFIERS Indicators; *Kansas; *State Capitals ABSTRACT This curriculum packet is about the Kansas state capitol. The packet contains six graphic organizers for students to complete. The packets are divided into three sections (with their accompanying graphic organizers): (1) "Symbolism of the Kansas Capitol Dome Statue" (Who Are the Kansa?; Finding Your Way; Say It Again); (2) "Topping the Dome: Selecting a Symbol" (What Are They Saying?; What's on Top?); and (3)"Names as Symbols" (Native American Place Names). For each section, the teacher is provided with a main point and background information for the lesson. Answers for the graphic organizers, when necessary, are provided. (BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Guide for Your\g,Dori@ Ad Astra, the statue by Richard Bergen, was placed on the Capitol Cr) dome October 2002 CD Curriculum Packet O For Teachers of Grades 4-7 © 2002 Kansas State Historical Society Prepared in consultation with the KA.NSAS Kansas State Department of Education STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY U.S. -

Curing Narratives: a Contemporary Poetics of Agency

CURING NARRATIVES: A CONTEMPORARY POETICS OF AGENCY By MELANIE ALMEDER A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1999 Copyright 1999 by Melanie Almeder ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am greatly indebted to the support of my family and the inspiration of their many ongoing successes: Robert, the brilliant philosopher: Virginia, the brilliant teacher and rescuer of animals: Lisa, the wonderful healer and activist: Chris, the insightful brother and the guardian of environmental good health. I have had the good fortune to work with inspiring teachers and guides at the University of Florida. I only hope Elizabeth Langland knows her importance to her students: she is a model toward which we aspire: a brilliant scholar, an insightful, original, and lucid writer, and a gracious, generous human being. I thank her for all of her time and care. Phil Wegner. Malini Schueller. John Cech. and Sue Rosser have all been generous with their time and comments and have pushed this project toward more complexity and invention. I am grateful to them. I am indebted, as well, to dear friends who have made this project possible with their support, conversation, and affirmation. I am indebted to Lori Amy. bravest of brave, who carefully read chapters, offered rigorous critique, and is a model of fresh, meaningful living and writing methods. Angela Bascik. lucid theorist among us. storyteller, truth teller, discussed this business of "agency" until the ultimate agent himself. Alexander, arrived. Monica Beth Fowler, queen of cameos, patron saint of strays, has reminded me of the myriad day-to-day humor and generosity that heals. -

TRASH CONVERTER: the Process of Contemporary Alchemy Collecting, Copying and Arranging in Sculptural Forms

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 2017+ University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2018 TRASH CONVERTER: The Process of Contemporary Alchemy Collecting, copying and arranging in sculptural forms Sarah Goffman University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1 University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Goffman, Sarah, TRASH CONVERTER: The Process of Contemporary Alchemy Collecting, copying and arranging in sculptural forms, Doctor of Creative Arts thesis, School of the Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2018. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

April 26, 1900

S PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. D^L ' Y~jToi!N A 1'KIL aAMRM4a HArr>&! PRICE TFIREE CENTS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862^VOlT 3»" I’OK 11. AM). MAINK, THUHSOA IMi, 1!>(>0._i (leaver to hlroeelf rorres tha IO hM KIT (I Mon nrglag flit If place TROl'BIFN OF KIR OW1. Una of ratreet Frenob's arrival paaoaral ami fall tl aMura forty enemy's THE AFFAIRWITR TURRET Bear tbs Holder evl lently, however, Ur« » BLOODY WORK. right •, there la nothing MU (or thrm alarmed the Boars for they evaou> ted I •ayllnllm bwttiflgtt _' their (Wrong poeltlon near lie Wet'e dorp Load**, April qilV'.-T dkfkatT WILL GET AWAY. taring the night, and It was oocopied by at tb« ltrttlab bug Chermslde'e division this morning. The In Status of 0 monetrd Infantry nnder fan Hamilton, No Change lb* t aether ail'. la Road la Ilia Re- Ataootatad Proa* aayla* la rUw g drevr the enemy off the korjw In the Negotiations. •tap* bln by lb* l)*«ri ■Mto* n»n n,lw-b rhood ef the vreterwotka without lag tbs A naan laa maaaaemo. Iba etoka* ia oascaltlrs on onr tide. ales af Kraal Britain, Fraer*. Aaatri* Slugkbr Philippine tirfH 1AL TO TUB rBBBBeJ “The lllgb lend brigade marohrd taly and Uaraaaay bat* aabad lb*If g*r- WaetlagSoa. April »-The defeat of tweaty-fonr miles yesterday to eopport M*»r rrniaeat* la fa<tra*l Mas aa la Goes Oo. eabater guay la Ida Senate, although Ueoeral Uemllton and halted for the a ala Bara ad Mat aa ex- Re- alia liar rial m II la bp ably aaa rata, la aoverlbotoa* Lord Roberts Chances of Catching night at Kilo Kraal, four miles ehort of Claims For Still fifing aa Indjjuaity be umiab gor*rnm*at baa aa* yad eaadlbg great dalsat altar aa ox reading Hannas i'cet. -

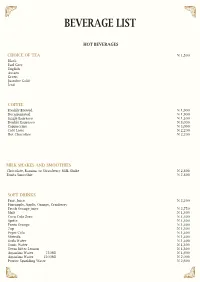

Beverage / Drinks

BEVERAGE LIST HOT BEVERAGES CHOICE OF TEA N 1,500 Black Earl Grey English Assam Green Jasmine Gold Iced COFFEE Freshly Brewed N 1,900 Decaffeinated N 1,900 Single Espresso N 1,500 Double Espresso N 3,000 Cappuccino N 3,000 Café Latte N 2,200 Hot Chocolate N 2,200 MILK SHAKES AND SMOOTHIES Chocolate, Banana, or Strawberry Milk Shake N 2,800 Fruits Smoothie N 2,800 SOFT DRINKS Fruit Juice N 2,200 Pineapple, Apple, Orange, Cranberry Fresh Orange juice N 2,750 Malt N 1,300 Coca Cola Zero N 1,300 Sprite N 1,300 Fanta Orange N 1,300 7up N 1,300 Pepsi Cola N 1,300 Mirinda N 1,300 Soda Water N 1,300 Tonic Water N 1,300 Teem Bitter Lemon N 1,300 Aquafina Water 750Ml N 1,600 Aquafina Water 1500Ml N 2,000 Perrier Sparkling Water N 2,600 ENERGY DRINKS Red Bull N 2,600 Power Horse N 2,600 BEER Star 600Ml N 1,900 Gulder 600Ml N 1,900 Heineken 600Ml N 2,600 Heineken 330Ml N 1,800 Guiness Stout 330Ml N 2,000 Guiness Stout 600Ml N 2,600 CLASSIC COCKTAILS Margarita N 5,000 Mexican cocktail consisting of tequila with cointreau and a lime juice Mojito N 6,000 Refreshing Cuban cocktail featuring rum, fresh mint and lime Cosmopolitan N 5,000 Combination of vodka, triple sec, cranberry juice and lime juice Manhattan N 5,000 A true classic made with whiskey, sweet vermouth and bitters. Martini Cocktail N 5,000 Made with gin and vermouth, garnished with an olive Bloody Mary N 5,000 Spicy tomato juice with vodka and a celery stick Pinacolada N 5,000 Traditional cocktail made with rum, cream of coconut and pineapple juice Americano N 5,000 Classic aperitif cocktail -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Uniti - Environmental Studies - Sbaa1204 Syllabus - Unit 1 - Introduction and Eco Systems

SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES UNITI - ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES - SBAA1204 SYLLABUS - UNIT 1 - INTRODUCTION AND ECO SYSTEMS Multidisciplinary Nature of Environmental Studies - Scope and Importance - Concept of sustainability and Sustainable Development. Eco systems- Meaning - Structure and function of ecosystem - Energy flow in an ecosystem - food chains, food webs and ecological succession - Forest ecosystem - Grassland ecosystem - Desert ecosystem - Aquatic ecosystems (ponds, streams, lakes, rivers, oceans, estuaries). ENVIRONMENT The word environment is derived from the French word ‗environner ‘which means to encircle or surround‘. Thus our environment can be defined as ―the Social, Cultural and Physical conditions that surround, affect and influence the survival, growth and development of people, animals and plants‖ This broad definition includes the natural world and the technological environment as well as the cultural and social contexts that shape human lives. It includes all factors (living and nonliving) that affect an individual organism or population at any point in the life cycle; set of circumstances surrounding a particular occurrence and all the things that surrounds us. Environment consists of four segments. Atmosphere- Blanket of gases surrounding the earth. Hydrosphere- Various water bodies present on the earth. Lithosphere- Contains various types of soils and rocks on the earth. Biosphere- Composed of all living organisms and their interactions with the environment. Multidisciplinary nature of environmental studies The Environment studies is a multi-disciplinary science because it comprises various branches of studies like chemistry, physics, medical science, life science, agriculture, public health, sanitary engineering etc. It is the science of physical phenomena in the environment. It studies about the sources, reactions, transport, effect and fate of physical and biological species in the air, water, soil and the effect of from human activity upon these. -

Understanding Others: Cultural and Cross-Cultural Studies and the Teaching of Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 352 649 CS 213 590 AUTHOR Trimmer, Joseph, Ed.; Warnock, Tilly, Ed. TITLE Understanding Others: Cultural and Cross-Cultural Studies and the Teaching of Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5562-6 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 269p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 55626-0015; $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cross Cultural Studies; Cultural Awareness; Cultural Context; Cultural Differences; Higher Education; *Literary Criticism; *Literature Appreciation; *Multicultural Education IDENTIFIERS Literature in Translation ABSTRACT This book of essays offers perspectives for college teachers facing the perplexities of today's focus on cultural issues in literature programs. The book presents ideas from 19 scholars and teachers relating to theories of culture-oriented criticism and teaching, contexts for these activities, and specific, culture-focused texts significant for college courses. The articles and their authors are as follows:(1) "Cultural Criticism: Past and Present" (Mary Poovey);(2) "Genre as a Social Institution" (James F. Slevin);(3) "Teaching Multicultural Literature" (Reed Way Dasenbrock);(4) "Translation as a Method for Cross-Cultural Teaching" (Anuradha Dingwaney and Carol Maier);(5) "Teaching in the Television Culture" (Judith Scot-Smith Girgus and Cecelia Tichi);(6) "Multicultural Teaching: It's an Inside Job" (Mary C. Savage); (7) "Chicana Feminism: In the Tracks of 'the' Native Woman" (Norma Alarcon);(8) "Current African American Literary Theory: Review and Projections" (Reginald Martin);(9) "Talking across Cultures" (Robert S. -

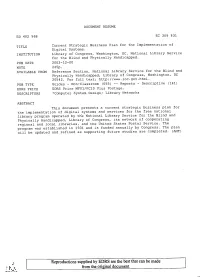

Current Strategic Business Plan for the Implementation of Digital

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 482 968 EC 309 831 Current Strategic Business Plan for the Implementation of TITLE Digital Systems. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 2003-12-00 NOTE 245p. AVAILABLE FROM Reference Section, National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20542. For full text: http://www.loc.gov.html. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Computer System Design; Library Networks ABSTRACT This document presents a current strategic business plan for the implementation of digital systems and servicesfor the free national library program operated by the National LibraryService for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, its networkof cooperating regional and local libraries, and the United StatesPostal Service. The program was established in 1931 and isfunded annually by Congress. The plan will be updated and refined as supporting futurestudies are completed. (AMT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ., . I a I a a a p , :71110i1 aafrtexpreve ..4111 AAP"- .4.011111rAPrip -"" Al MI 1111 U DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Oth of Educattonal Research and Improvement ED ATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION .a.1111PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND CENTER (ERIC) DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS IN" This document has been reproduced as BEEN GRANTED BY received from the person