RAS.Journal2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Poetry of the Nineteenth Century

“Modern” Science and Technology in “Classical” Chinese Poetry of the Nineteenth Century J. D. Schmidt 㕥⎱䐆 University of British Columbia This paper is dedicated to the memory of Prof. Daniel Bryant (1942-2014), University of Victoria, a great scholar and friend. Introduction This paper examines poetry about science and technology in nineteenth- century China, not a common topic in poetry written in Classical Chinese, much less in textbook selections of classical verse read in high school and university curricula in China. Since the May Fourth/New Culture Movement from the 1910s to the 1930s, China’s literary canon underwent a drastic revision that consigned a huge part of its verse written after the year 907 to almost total oblivion, while privileging more popular forms from after that date that are written in vernacular Chinese, such as drama and novels.1 The result is that today most Chinese confine their reading of poetry in the shi 娑 form to works created before the end of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), missing the rather extensive body of verse about scientific and technological subjects that began in the Song Dynasty (960-1278), largely disappeared in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), and then flourished as never before in the late Qing period (1644-1912). Except for a growing number of specialist scholars in China, very few Chinese readers have explored the poetry of the nineteenth century—in my opinion, one of the richest centuries in classical verse— thinking that the writing of this age is dry and derivative. Such a view is a product of the culture wars of the early twentieth century, but the situation has not been helped by the common name given to the most important literary group of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Qing Dynasty Song School (Qingdai Songshi pai 㶭ẋ⬳娑㳦), a term which suggests that its poetry is imitative of earlier authors, particularly those of the Song Dynasty. -

Notes and References

Notes and References 1 China and Britain: A Theme of National Liberation 1. G.C. Allen and Audrey G. Donnithorne, Western Enterprise in Far Eastern Economic Development: China and Japan, 1954, pp. 265-68; Cheng Yu-kwei, Foreign Trade and Industrial Development of China, 1956, p. 8. 2. Wu Chengming, Di Guo Zhu Yi Zai Jiu Zhong Guo De Tou Zi (The Investments of Imperialists in Old China), 1958, p. 41. 3. Jerome Ch'en, China and the West, p. 207. See also W. Willoughby, Foreign Rights and Interests in China, vol. 2, 1927, pp. 544-77, 595-8, 602-13. 4. Treaty of Tientsin, Art. XXXVII, in William F. Mayers, Treaties Between the Empire of China and Foreign Powers, 1906, p. 17. 5. Shang Hai Gang Shi Hua (Historical Accounts of the Shanghai Port), 1979, pp. 36-7. 6. See Zhao Shu-min, Zhong Guo Hai Guan Shi (History of China's Maritime Customs), 1982, pp. 22-46. With reference to the Chinese authorities' agreement to foreign inspectorate, see W. Willoughby, op.cit., vol. 2, pp. 769-70. 7. See S.F. Wright, China's Struggle for Tariff Autonomy, 1938; Zhao Shu-min, op. cit. pp. 27-38. 8. See Liu Kuang-chiang, Anglo-American Steamship Rivalry in China, 1862-1874, 1962; Charles Drage, Taikoo, 1970; Colin N. Crisswell, The Taipans, Hong Kong Merchant Princes, 1981. See also Historical Ac counts of the Shanghai Port, pp. 193-240; Archives of the China Mer chant's Steam Navigation Company, Maritime Transport Administration Bureau of the Ministry of Transport, Shanghai. 9. -

Andreas Schmid Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ANDREAS SCHMID Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise, Anthony Yung Date: 27 Apr 2008 Duration: about 2 hours Location: Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong Question (Q): Why did you go to China? Where you and what were you doing? Who are some of the artists that you encountered and what do you think about them? What were the artists reading and what are your comments on those materials? Andreas Schmid (AS): I graduated from the Art Academy in Stuttgart in 1981, studying painting. My paintings were, at that time, very different from German painters like Kiefer in that they always have free space, and transparency of layers of space in them. I painted with oil and acrylic, and it was different from my colleagues/contemporaries. I became interested in the idea of space, of Chinese Art, classical Chinese art, like Ni Zan [倪赞] in the fourteenth century. Then I went to Cologne and saw a collection of Japanese Buddhist writings collected by Seiko Kono , abbot of the Daian-ji temple in Nara City , Japan. I would like to know the line from another side, because lines played the most important role graphically in my paintings. So I tried contacting organizations that would support me, and they informed me there was only one woman who went to China as an artist from Germany with the support of the German exchange service. I went to see her, and she had studied in Hangzhou one year ago at that time (1980). She studied birds and flowers painting. She told me, if you want to do this, you should go to China, it is interesting. -

China and India Timbuktu Books & Walkabout Books

CHINA AND INDIA An e-list jointly issued by TIMBUKTU BOOKS & WALKABOUT BOOKS Seattle, WA Laguna Hills, CA JUNE 2019 Terms: All items are subject to prior sale and are returnable within two weeks of receipt for any reason as long as they are returned in the same condition as sent. Shipping will be charged at cost and sales tax will be added if applicable. Payment may be made by check, credit card, or paypal. Institutions will be billed according to their needs. Standard courtesies to the trade. Susan Eggleton Elizabeth Svendsen [email protected] [email protected] 206-257-8751 949-588-6055 www.timbuktubooks.net www.walkaboutbooks.net PART I: CHINA AND WESTERN PERCEPTIONS OF THE CHINESE An Early Chinese Effort to Develop Segregated Schools for Students with Special Needs 1. [BLIND SCHOOL] Niles, Mary; Durham, Lucy. Ming Sam School for the Blind, Canton, China, 1919. 12 pp, 5.5 x 8.5 inches, in original stapled wrappers. Light stain to upper left corner of cover and Chinese characters written on the front; very good. The first-known formal school for blind or deaf students in China was set up in 1887 in Shandong Province. The Ming Nam School followed just a few years later in 1891 in Canton. As recounted in this booklet, Dr. Mary Niles, who had come to China as the first woman missionary doctor at a Canton hospital, became aware of one of the city’s blind “singing girls." The girl, with others like her, had been sold by her parents and forced to sing on the streets at night. -

Patons 235 Baby S Choice

3 FOR A GREAT OCCASION... Two lovely shawls— one to crochet, one to knit, and a tfelicate lacy christening dress with tibhoti trimrning which you can make to a long or short length. p 1-®' ^rc:- ..,>- mmmm i‘f^>. ; V'. ' : -‘s'fe' ‘i - *-7 -. 1^ ''' v^vA'iv An all-in-one and a hooded jacket with simple bunny motifs make a warm and attractive outfit. ' .?' - ^^^-v ^v A;/-7.^^v^ ' /7':7v%^ K:: .:>,. V. = ' *'V;yy^ : ?k ’:^/A//:^A ' • — — '* i,‘y » 1—- : > • > >y ' ; -- - 1v : t Vtv-,- - > .r' r-^T-- ™ -^ J . 5 ^Patons BABY CHOICE beg -beginning; alt=alternate; rep-repeat; lengths of yarn. Knot ends together, insert Caution patt=pattern; cm =centi metres; in = inches; pencil at each end in front of knot between tt is essential to work to the stated tension, mm ^miHimetres; O^no sts, rows or times. lengths of yam (Diag. A). Facing each other and Patons and Baldwins Limited cannot and holding yarn together between thumb accept responsibility for the finished product Ml =make 1 stitch by picking up horizontal finger in front of knot, turn pencil clock- lying before stitch into and if any yarn other than the recomnnended loop next and working wise {B). Continue until strands are tightly Patons yarns is used. back of it. twisted, then bring pencils together and allow IVnK=make 1 knitwayfl by picking up loop cord to twist (C). Remove pencils and knot Abbreviations that lies between st just worked and follow- ends. K=knit; P=purl; KB=knitinto back of stitch; ing St and knitting into back of it. -

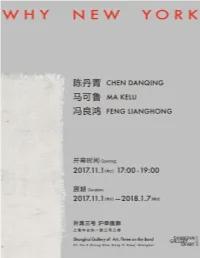

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

Penang Travel Tale

Penang Travel Tale The northern gateway to Malaysia, Penang’s the oldest British settlement in the country. Also known as Pulau Pinang, the state capital, Georgetown, is a UNESCO listed World Heritage Site with a collection of over 12,000 surviving pre-war shop houses. Its best known as a giant beach resort with soft, sandy beaches and plenty of upscale hotels but locals will tell you that the island is the country’s unofficial food capital. SIM CARDS AND DIALING PREFIXES Malaysia’s three main cell phone service providers are Celcom, Digi and WEATHER Maxis. You can obtain prepaid SIM cards almost anywhere – especially Penang enjoys a warm equatorial climate. Average temperatures range inside large-scale shopping malls. Digi and Maxis are the most popular between 29°C - 35 during the day and 26°C - 29°C during the night; services, although Celcom has the most widespread coverage in Sabah however, being an island, temperatures here are often higher than the and Sarawak. Each state has its own area code; to make a call to a mainland and sometimes reaches as high as 35°C during the day. It’s best landline in Penang, dial 04 followed by the seven-digit number. Calls to not to forget your sun block – the higher the SPF, the better. It’s mostly mobile phones require a three-digit prefix, (Digi = 016, Maxis = 012 and sunny throughout the day except during the monsoon seasons when the Celcom = 019) followed by the seven digit subscriber number. island experiences rainfall in the evenings. http://www.penang.ws /penang-info/clim ate.htm CURRENCY GETTING AROUND Malaysia coinage is known as the Ringgit Malaysia (MYR). -

The Womanly Physician in Doctor Zay and Mona Maclean, Medical Student

25 영어영문학연구 제45권 제3호 Studies in English Language & Literature (2019) 가을 25-40 http://dx.doi.org/10.21559/aellk.2019.45.3.002 The Womanly Physician in Doctor Zay and Mona Maclean, Medical Student Ji-Eun Kim (Yonsei University) Kim, Ji-Eun. “The Womanly Physician in Doctor Zay and Mona Maclean, Medical Student.” Studies in English Language & Literature 45.3 (2019): 25-40. This paper investigates the representation of women physicians in two novels - an American novel titled Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s Doctor Zay (1882), and a British novel, Dr. Margaret Todd’s Mona Maclean, Medical Student (1892). While also looking at differences these individual novels have, this paper aims to look at how these transatlantic nineteenth century novels have common threads of linking women doctors with the followings: the constant referral to “womanliness,” the question of class affiliations, marriage, and medical modernity. While the two doctor novels end with the conventional marriage plot, these novels fundamentally questioned the assumption that women doctors could only cure women and children. These texts also tried to bend existing gender roles and portrayed women doctors who were deemed as “womanly.” (Yonsei University) Key Words: Doctor Zay, Mona Maclean Medical Student, woman doctors, womanliness, nineteenth-century I. Introduction What common ground do Dr. Quinn of “Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman” (1993-98), Dana Scully in “The X-Files” (1993-2002), Meredith Gray, Miranda Bailey and Christina Yang in “Grey’s Anatomy” (since 2005) have? These prime-time U.S. TV dramas depict impressive women physicians successively juggling their medical 26 Ji-Eun Kim careers, tough responsibilities and hectic personal lives. -

1 Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I Have Been

Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I have been unconsciously entangled in a historical process of the making of modern Buddhism. There was a Chinese temple beside my house in Penang, Malaysia. The main deity was likely a deified imperial court officer, though no historical record documented his origin. A mosque serenely resided along the main street approximately 50 meters from my house. At the end of the street was a Hindu temple decorated with colorful statues. Less than five minutes’ walk from my house was a Buddhist association in a two-storey terrace. During my childhood, the Chinese temple was a playground. My friends and I respected the deities worshipped there but sometimes innocently stole sweets and fruits donated by worshippers as offerings. Each year, three major religious events were organized by the temple committee: the end of the first lunar month marked the spring celebration of a deity in the temple; the seventh lunar month was the Hungry Ghost Festival; and the eighth month honored, She Fu Da Ren, the temple deity’s birthday. The temple was busy throughout the year. Neighbors gathered there to chat about national politics and local gossip. The traditional Chinese temple was thus deeply rooted in the community. In terms of religious intimacy with different nearby temples, the Chinese temple ranked first, followed by the Hindu temple and finally, the mosque, which had a psychological distant demarcated by racial boundaries. I accompanied my mother several times to the Hindu temple. Once, I asked her why she prayed to a Hindu deity. -

Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society for the Year

O ~—L ^T ~~ o ?Ui JOURNAL OF THE NORTH- CHINA BRANCH OF THE BOYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY VOLUME XLIX— 1918 CONTENTS. PAGE PROCEEDINGS ix RIVER PROBLEMS IN CHINA. By Herbert Chatley, D. Sc. ... 1 SOME NOTES ON LAND-BIRDS. By H. E. Laver 13 ANIMISTIC ELEMENTS IN MOSLEM PRAYER. By Samuel M. Zwemer, F.R.G.S 38 THE EIGHT IMMORTALS OF THE TAOIST RELIGION. By Peter C. Ling 53 A CHAPTER ON FOLKLORE: I.—The Kite Festival in Foochow, China. By Lewis Hodous, D.D 76 II.— On a Method of Divination Practised at Foochow. By H. L. Harding 82 HI—Notes on the Tu T'ien Hui (fP ^ #) held at Chinkiang on the 31st May, 1917. By H. A. Ottewill 86 IV.—The Domestic Altar. By James Hutson 93 KU K'AI-CHIH'S SCROLL IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM. By J. C. Ferguson, Ph.D 101 THE THEISTIC IMPORT OF THE SUNG PHILOSOPHY. By J. P. Bruce, M.A 111 A CASE OF RITUALISM. By Evan Morgan 128 CHINESE PUZZLEDOM. By Charles Kliene, F.R.G.S. ... 144 REVIEWS OF RECENT BOOKS 160 NOTES AND QUERIES 200 ADDITIONS TO THE LIBRARY 208 LIST OF MEMBERS 211 A I: Application for Membership, stating the Name (in full) r Nationality, Profession and Address of Applicants, should be forwarded to "The SecretaE^JJorth-China Branch of the Eoyal Asiatic Society, (Shanghai^ The name should be proposed and seconded by members of the Society, but where circumstances prevent the observance of this Bule, the Council is prepared to consider applications with such references as may be given. -

The Generalissimo

the generalissimo ګ The Generalissimo Chiang Kai- shek and the Struggle for Modern China Jay Taylor the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 .is Chiang Kai- shek’s surname ګ The character Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Taylor, Jay, 1931– The generalissimo : Chiang Kai- shek and the struggle for modern China / Jay Taylor.—1st. ed. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 03338- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Chiang, Kai- shek, 1887–1975. 2. Presidents—China— Biography. 3. Presidents—Taiwan—Biography. 4. China—History—Republic, 1912–1949. 5. Taiwan—History—1945– I. Title. II. Title: Chiang Kai- shek and the struggle for modern China. DS777.488.C5T39 2009 951.04′2092—dc22 [B]â 2008040492 To John Taylor, my son, editor, and best friend Contents List of Mapsâ ix Acknowledgmentsâ xi Note on Romanizationâ xiii Prologueâ 1 I Revolution 1. A Neo- Confucian Youthâ 7 2. The Northern Expedition and Civil Warâ 49 3. The Nanking Decadeâ 97 II War of Resistance 4. The Long War Beginsâ 141 5. Chiang and His American Alliesâ 194 6. The China Theaterâ 245 7. Yalta, Manchuria, and Postwar Strategyâ 296 III Civil War 8. Chimera of Victoryâ 339 9. The Great Failureâ 378 viii Contents IV The Island 10. Streams in the Desertâ 411 11. Managing the Protectorâ 454 12. Shifting Dynamicsâ 503 13. Nixon and the Last Yearsâ 547 Epilogueâ 589 Notesâ 597 Indexâ 699 Maps Republican China, 1928â 80–81 China, 1929â 87 Allied Retreat, First Burma Campaign, April–May 1942â 206 China, 1944â 293 Acknowledgments Extensive travel, interviews, and research in Taiwan and China over five years made this book possible. -

History, Background, Context

42 History, Background, Context The history of the Qing dynasty is of course the history of hundreds upon hundreds of millions of people. The volume, density, and complexity of the information contained in this history--"history" in the sense of the totality of what really happened and why--even if it were available would be beyond the capacity of any single individual to comprehend. Thus what follows is "history" in another sense--a selective recreation of the past in written form--in this case a sketch of basic facts about major episodes and events drawn from secondary sources which hopefully will provide a little historical background and allow the reader to place Pi Xirui and Jingxue lishi within a historical context. While the history of the Qing dynasty proper begins in 1644, history is continuous. The Jurchen (who would later call themselves Manchus), a northeastern tribal people, had fought together with the Chinese against the Japanese in the 1590s when the Japanese invaded Korea. However in 1609, after a decade of increasing military strength, their position towards the Chinese changed, becoming one of antagonism. Nurhaci1 努爾哈赤 (1559-1626), a leader who had united the Jurchen tribes, proclaimed himself to be their chieftain or Khan in 1616 and also proclaimed the 1See: ECCP, p.594-9, for his biography. 43 founding of a new dynasty, the Jin 金 (also Hou Jin 後金 or Later Jin), signifying that it was a continuation of the earlier Jurchen dynasty which ruled from 1115-1234. In 1618, Nurhaci led an army of 10,000 with the intent of invading China.