Bachelor's Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LATEX for Beginners

LATEX for Beginners Workbook Edition 5, March 2014 Document Reference: 3722-2014 Preface This is an absolute beginners guide to writing documents in LATEX using TeXworks. It assumes no prior knowledge of LATEX, or any other computing language. This workbook is designed to be used at the `LATEX for Beginners' student iSkills seminar, and also for self-paced study. Its aim is to introduce an absolute beginner to LATEX and teach the basic commands, so that they can create a simple document and find out whether LATEX will be useful to them. If you require this document in an alternative format, such as large print, please email [email protected]. Copyright c IS 2014 Permission is granted to any individual or institution to use, copy or redis- tribute this document whole or in part, so long as it is not sold for profit and provided that the above copyright notice and this permission notice appear in all copies. Where any part of this document is included in another document, due ac- knowledgement is required. i ii Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What is LATEX?..........................1 1.2 Before You Start . .2 2 Document Structure 3 2.1 Essentials . .3 2.2 Troubleshooting . .5 2.3 Creating a Title . .5 2.4 Sections . .6 2.5 Labelling . .7 2.6 Table of Contents . .8 3 Typesetting Text 11 3.1 Font Effects . 11 3.2 Coloured Text . 11 3.3 Font Sizes . 12 3.4 Lists . 13 3.5 Comments & Spacing . 14 3.6 Special Characters . 15 4 Tables 17 4.1 Practical . -

Reflections from the Developments of School Science Curricula

Imitation game: Reflections from the developments of school science curricula SONG, Jinwoong (宋眞雄) Department of Physics Education, Seoul National University What will fulfill this need can be stated in equally simple terms. It is, ironically enough, that science be taught as science. (Joseph J. Schwab, 1962: 188-9) 1.Introduction The Imitation Game is a 2014 British historical drama film directed by Morten Tyldu m and written by Graham Moore, based on the biography Alan Turing: The Enigma by A ndrew Hodges. It stars Benedict Cumberbatch as British cryptanalyst Alan Turing, who dec rypted German intelligence codes for the British government during the Second World War (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Imitation_Game). The ’Imitation Game’ refers to so-calle d ‘Turing Test’ which is a test for artificial intelligence suggested by a famous British ma thematician, Alan Turing (1912-54), who is known as the father of the computer. Through his paper, “Computing machinery and intelligence” (1950), Tuning gave a conceptual fou ndation of AI (Artificial Intelligence), by suggesting the Turing Test, “a test of a machine’ s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a h uman.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turing_test) Science is now considered as one of the core (often three of them) subjects across th e world, together with the national language and mathematics. For example, in PISA studi es, science is included in the three main areas, with literacy and mathematics (e.g. OECD, 2018). And, in TIMSS studies, science and mathematics are the two main subjects for th e international comparison (https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/). -

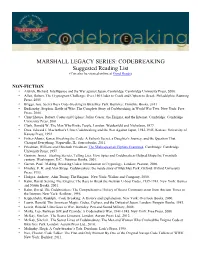

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

LIST of MOVIES from PAST SFFR MOVIE NIGHTS (Ordered from Recent to Old) *See Editing Instructions at Bottom of Document

LIST OF MOVIES FROM PAST SFFR MOVIE NIGHTS (Ordered from recent to old) *See editing Instructions at bottom of document 2020: Jan – Judy Feb – Papi Chulo Mar - Girl Apr - GAME OVER, MAN May - Circus of Books 2019: Jan – Mario Feb – Boy Erased Mar – Cakemaker Apr - The Sum of Us May – The Pass June – Fun in Boys Shorts July – The Way He Looks Aug – Teen Spirit Sept – Walk on the Wild Side Oct – Rocketman Nov – Toy Story 4 2018: Jan – Stronger Feb – God’s Own Country Mar -Beach Rats Apr -The Shape of Water May -Cuatras Lunas( 4 Moons) June -The Infamous T and Gay USA July – Padmaavat Aug – (no movie night) Sep – The Unknown Cyclist Oct - Love, Simon Nov – Man in an Orange Shirt Dec – Mama Mia 2 2017: Dec – Eat with Me Nov – Wonder Woman (2017 version) Oct – Invaders from Mars Sep – Handsome Devil Aug – Girls Trip (at Westfield San Francisco Centre) Jul – Beauty and the Beast (2017 live-action remake) Jun – San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival selections May – Lion Apr – La La Land Mar – The Heat Feb – Sausage Party Jan – Friday the 13th 2016: Dec - Grandma Nov – Alamo Draft House Movie Oct - Saved Sep – Looking the Movie Aug – Fourth Man Out, Saving Face July – Hail, Caesar June – International Film festival selections May – Selected shorts from LGBT Film Festival Apr - Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (Run, Milkha, Run) Mar – Trainwreck Feb – Inside Out Jan – Best In Show 2015: Dec - Do I Sound Gay? Nov - The best of the Golden Girls / Boys Oct - Love Songs Sep - A Single Man Aug – Bad Education Jul – Five Dances Jun - Broad City series May – Reaching for the Moon Apr - Boyhood Mar - And Then Came Lola Feb – Looking (Season 2, Episodes 1-4) Jan – The Grand Budapest Hotel 2014: Dec – Bad Santa Nov – Mrs. -

Books for the College Bound Fiction

BOOKS FOR THE COLLEGE BOUND FICTION Anderson, Sherwood. Winesburg, Ohio, 1919. A collection of short stories lays bare the life of a small town in the Midwest. 247 p. A5492WI Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice, 1813. “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” This witty comedy of manners explores the intricacies of courtship in 18th-century England. 281 p. A933PR Bellamy, Edward. Looking Backward: 2000-1887, 1887. Written in 1887 about a young man who travels in time to a utopian year 2000, where economic security and a healthy moral environment have reduced crime. 470 p. B4357L Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451, 1951. Enter a futuristic world where reading is prohibited because it stimulates thought, and firemen “protect” society by burning books. 179 p. B7982F Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre, 1847. Jane Eyre, a penniless orphan, is engaged as governess for the mysterious Mr. Rochester. 248 p. B8695J Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights, 1847. One of the first gothic novels. Passion, hate, and revenge abound in the turbulent story of Heathcliff and Catherine’s obsessive love. 390 p. B8697W Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865. Alice falls down a rabbit-hole and enters the whimsical, nonsensical world of the Queen of Hearts, Cheshire cat, and Mad Hatter. 143 p. C3196AL Cather, Willa. My Ántonia, 1918. Soulful portrait of Ántonia Shimerda, a Czech immigrant who faces heartbreak, disillusionment, and social ostracism in frontier Nebraska. 238 p. C363MY Chopin, Kate. The Awakening, 1899. The story of a New Orleans woman who abandons her husband and children to search for love and self-understanding. -

Discipleship in the Works of Christopher Isherwood

Prague Journal of English Studies Volume 8, No. 1, 2019 ISSN: 1804-8722 (print) '2,10.2478/pjes-2019-0005 ISSN: 2336-2685 (online) A Bond Stronger Than Marriage: Discipleship in the Works of Christopher Isherwood Kinga Latała Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland is paper is concerned with Christopher Isherwood’s portrayal of his guru-disciple relationship with Swami Prabhavananda, situating it in the tradition of discipleship, which dates back to antiquity. It discusses Isherwood’s (auto)biographical works as records of his spiritual journey, infl uenced by his guru. e main focus of the study is My Guru and His Disciple, a memoir of the author and his spiritual master, which is one of Isherwood’s lesser-known books. e paper attempts to examine the way in which a commemorative portrait of the guru, suggested by the title, is incorporated into an account of Isherwood’s own spiritual development. It discusses the sources of Isherwood’s initial prejudice against religion, as well as his journey towards embracing it. It also analyses the facets of Isherwood and Prabhavananda’s guru-disciple relationship, which went beyond a purely religious arrangement. Moreover, the paper examines the relationship between homosexuality and religion and intellectualism and religion, the role of E. M. Forster as Isherwood’s secular guru, the question of colonial prejudice, as well as the reception of Isherwood’s conversion to Vedanta and his religious works. Keywords Christopher Isherwood; Swami Prabhavananda; My Guru and His Disciple; discipleship; guru; memoir e present paper sets out to explore Christopher Isherwood’s depiction of discipleship in My Guru and His Disciple (1980), as well as relevant diary entries and letters. -

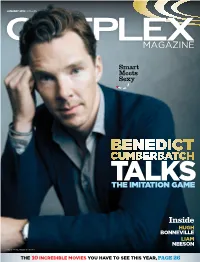

Benedict Cumberbatch Talks the Imitation Game

JANUARY 2015 | VOLUME 16 | NUMBER 1 Smart Meets Sexy BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH TALKS THE IMITATION GAME Inside HUGH BONNEVILLE LIAM NEESON PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 41619533 THE 10 INCREDIBLE MOVIES YOU HAVE TO SEE THIS YEAR, PAGE 26 CONTENTS JANUARY 2015 | VOL 16 | Nº1 COVER STORY 40 GENIUS ROLE Benedict Cumberbatch’s fervent fans won’t be disappointed with his latest role. The Imitation Game casts the 38-year-old Brit as Alan Turing, a gay, mathematical genius who helped hasten the end of WWII. Here he talks about bringing Turing to life and his various other talents BY INGRID RANDOJA REGULARS 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 8 SNAPS 10 IN BRIEF 14 SPOTLIGHT: CANADA 16 ALL DRESSED UP 20 IN THEATRES 44 CASTING CALL 47 RETURN ENGAGEMENT 48 AT HOME 50 FINALLY… FEATURES IMAGE HARGRAVE/AUGUST AUSTIN BY PHOTO COVER 26 2015’S BIG PICS! 32 FABLED CAST 34 MAN OF ACTION 38 PAPA BEAR It’s going to be an epic year We break down which famous Taken 3 star Liam Neeson Paddington’s Hugh Bonneville at the movies. We take you actors play which well-known talks about his longtime says playing father figure to a through the 10 films you must fairy tale characters in love of action movies, and mischievous talking bear gave see, starting with the return of the musical extravaganza recent decision to get clean him the chance to revisit his Star Wars! Into the Woods and healthy own childhood BY INGRID RANDOJA BY INGRID RANDOJA BY BOB STRAUSS BY INGRID RANDOJA JANUARY 2015 | CINEPLEX MAGAZINE | 3 EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHER SALAH BACHIR EDITOR MARNI WEISZ DEPUTY EDITOR INGRID RANDOJA ART DIRECTOR TREVOR THOMAS STEWART ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR STEVIE SHIPMAN VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION SHEILA GREGORY CONTRIBUTORS LEO ALEFOUNDER, BOB STRAUSS ADVERTISING SALES FOR CINEPLEX MAGAZINE AND LE MAGAZINE CINEPLEX IS HANDLED BY CINEPLEX MEDIA. -

Why Python for Chatbots

Schedule: 1. History of chatbots and Artificial Intelligence 2. The growing role of Chatbots in 2020 3. A hands on look at the A.I Chatbot learning sequence 4. Q & A Session Schedule: 1. History of chatbots and Artificial Intelligence 2. The growing role of Chatbots in 2020 3. A hands on look at the A.I Chatbot learning sequence 4. Q & A Session Image credit: Archivio GBB/Contrasto/Redux History •1940 – The Bombe •1948 – Turing Machine •1950 – Touring Test •1980 Zork •1990 – Loebner Prize Conversational Bots •Today – Siri, Alexa Google Assistant Image credit: Photo 172987631 © Pop Nukoonrat - Dreamstime.com 1940 Modern computer history begins with Language Analysis: “The Bombe” Breaking the code of the German Enigma Machine ENIGMA MACHINE THE BOMBE Enigma Machine image: Photographer: Timothy A. Clary/AFP The Bombe image: from movie set for The Imitation Game, The Weinstein Company 1948 – Alan Turing comes up with the concept of Turing Machine Image CC-BY-SA: Wikipedia, wvbailey 1948 – Alan Turing comes up with the concept of Turing Machine youtube.com/watch?v=dNRDvLACg5Q 1950 Imitation Game Image credit: Archivio GBB/Contrasto/Redux Zork 1980 Zork 1980 Text parsing Loebner Prize: Turing Test Competition bit.ly/loebnerP Conversational Chatbots you can try with your students bit.ly/MITsuku bit.ly/CLVbot What modern chatbots do •Convert speech to text •Categorise user input into categories they know •Analyse the emotion emotion in user input •Select from a range of available responses •Synthesize human language responses Image sources: Biglytics -

44-Christopher Isherwood's a Single

548 / RumeliDE Journal of Language and Literature Studies 2020.S8 (November) Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life / G. Güçlü (pp. 548-562) 44-Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life Gökben GÜÇLÜ1 APA: Güçlü, G. (2020). Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (Ö8), 548-562. DOI: 10.29000/rumelide.816962. Abstract Beginning his early literary career as an author who nurtured his fiction with personal facts and experiences, many of Christopher Isherwood’s novels focus on constructing an identity and discovering himself not only as an adult but also as an author. He is one of those unique authors whose gradual transformation from late adolescence to young and middle adulthood can be clearly observed since he portrays different stages of his life in fiction. His critically acclaimed novel A Single Man, which reflects “the afternoon of his life;” is a poetic portrayal of Isherwood’s confrontation with ageing and death anxiety. Written during the early 1960s, stormy relationship with his partner Don Bachardy, the fight against cancer of two of his close friends’ (Charles Laughton and Aldous Huxley) and his own health problems surely contributed the formation of A Single Man. The purpose of this study is to unveil how Isherwood’s midlife crisis nurtured his creativity in producing this work of fiction. From a theoretical point of view, this paper, draws from literary gerontology and ‘the Lifecourse Perspective’ which is a theoretical framework in social gerontology. -

Mohler's New Book on the Lord's Prayer Billy Graham Remembered

07 VOLUME 16 MARCH 2018 A NEWS PUBLICATION OF THE SOUTHERN BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY The Gift of Singleness Mohler’s new book Billy Graham Stinson on Marriage on The Lord’s Prayer Remembered and Singleness Looking for a fun summer job? DON’T WASTE YOUR What to Expect KID’S SUMMER Pay $300 a week A Gospel-Focused Camp Experience Gospel Training in the Heart of St. Matthews Bible Teaching Opportunities Background Checks Required CHEAPER THAN SCHEDULE Fun Work Environment A BABYSITTER 1 2 3 Weekends Off For Rising 1st Graders to Rising 6th Graders Bright and early Next, it’s out Of course, lunch. we have morning the door for Bring your own! celebration, a some high You know what $200 a week/$50 a day gospel-infused energy games you like (and time of worship and activities. can’t eat) better and fun to wake Think, gaga ball, than we do. Safe Location at your kids up and basketball, and center the day water games. Sojourn East on Jesus. Mon-Fri 8-4 4 5 6 Trained Christian Staff Midday, we focus After that, MORE Then, we end the on the heart with games and day how it began, Bible lessons fun. You know, with a celebration Tons of Fun and small group the outdoor, focused on discussion times. teambuilding, worshipping Jesus We want to plant joy-filled kind. and having fun. For More Information seeds to help grow Think, bouncy and to register visit your kids into houses and slip- gocrossings.org/daycamps followers of Jesus. n-slides. -

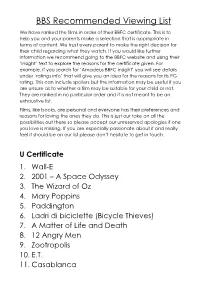

BBS Recommended Viewing List

BBS Recommended Viewing List We have ranked the films in order of their BBFC certificate. This is to help you and your parents make a selection that is appropriate in terms of content. We trust every parent to make the right decision for their child regarding what they watch. If you would like further information we recommend going to the BBFC website and using their ‘Insight’ text to explore the reasons for the certificate given. For example, if you search for ‘Amadeus BBFC insight’ you will see details under ‘ratings info’ that will give you an idea for the reasons for its PG rating. This can include spoilers but the information may be useful if you are unsure as to whether a film may be suitable for your child or not. They are ranked in no particular order and it is not meant to be an exhaustive list. Films, like books, are personal and everyone has their preferences and reasons for loving the ones they do. This is just our take on all the possibilities out there so please accept our unreserved apologies if one you love is missing. If you are especially passionate about it and really feel it should be on our list please don’t hesitate to get in touch. U Certificate 1. Wall-E 2. 2001 – A Space Odyssey 3. The Wizard of Oz 4. Mary Poppins 5. Paddington 6. Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) 7. A Matter of Life and Death 8. 12 Angry Men 9. Zootropolis 10. E.T. 11. Casablanca 12. Sense and Sensibility 13. -

Inequality in 900 Popular Films: Gender, Race/Ethnicity, LGBT, & Disability from 2007‐2016

July 2017 INEQUALITY IN POPULAR FILMS MEDIA, DIVERSITY, & SOCIAL CHANGE INITIATIVE USC ANNENBERG MDSCInitiative Facebook.com/MDSCInitiative THE NEEDLE IS NOT MOVING ON SCREEN FOR FEMALES IN FILM Prevalence of female speaking characters across 900 films, in percentages Percentage of 900 films with 32.8 32.8 Balanced Casts 12% 29.9 30.3 31.4 31.4 28.4 29.2 28.1 Ratio of males to females 2.3 : 1 Total number of ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ speaking characters 39,788 LEADING LADIES RARELY DRIVE THE ACTION IN FILM Of the 100 top films in 2016... And of those Leads and Co Leads*... Female actors were from underrepresented racial / ethnic groups Depicted a 3 Female Lead or (identical to 2015) Co Lead 34 Female actors were at least 45 years of age or older 8 (compared to 5 in 2015) 32 films depicted a female lead or co lead in 2015. *Excludes films w/ensemble casts GENDER & FILM GENRE: FUN AND FAST ARE NOT FEMALE ACTION ANDOR ANIMATION COMEDY ADVENTURE 40.8 36 36 30.7 30.8 23.3 23.4 20 20.9 ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ ‘ % OF FEMALE SPEAKING % OF FEMALE SPEAKING % OF FEMALE SPEAKING CHARACTERS CHARACTERS CHARACTERS © DR. STACY L. SMITH GRAPHICS: PATRICIA LAPADULA PAGE THE SEXY STEREOTYPE PLAGUES SOME FEMALES IN FILM Top Films of 2016 13-20 yr old 25.9% 25.6% females are just as likely as 21-39 yr old females to be shown in sexy attire 10.7% 9.2% with some nudity, and 5.7% 3.2% MALES referenced as attractive. FEMALES SEXY ATTIRE SOME NUDITY ATTRACTIVE HOLLYWOOD IS STILL SO WHITE WHITE .% percentage of under- represented characters: 29.2% BLACK .% films have NO Black or African American speaking characters HISPANIC .% 25 OTHER % films have NO Latino speaking characters ASIAN .% 54 films have NO Asian speaking *The percentages of Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Other characters characters have not changed since 2007.