Diplomarbeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AV Austria Innsbruck

AV Austria Innsbruck Home Die Austria Die Geschichte der AV Austria Innsbruck Austrier Blätter Folgend geben wir lediglich einen kurzen Überblick und Auszüge von unserer Verbindungsgeschichte: Programm Interesse? Die ersten Jahre Intern Unsere Verbindung wurde am 9. Juni 1864 von zwei Kontakt Philosophiestudenten, Franz Schedle und Johann Wolf, gegründet. Sie ist damit die älteste katholische Verbindung Österreichs und die "vierte" Verbindung, die dem damals noch Deutschland, Österreich und Tschechien umfassenden Cartellverband (CV) beitrat. Die Anfangsjahre waren von der liberalen und kirchenfeindlichen Denkweise vieler Professoren und Studenten an der Universität, speziell der schlagenden Corps, und daraus resultierenden Anfeindungen bis hin zu tätlichen Übergriffen geprägt. Ein gewaltiger Dorn im Auge war den bestehenden Corps vor allem die Ablehnung der Mensur, was zu vielen Provokationen und Ehrbeleidigungen führte. Ein in Couleurkreisen relativ bekannter Austrier beispielsweise, Josef Hinter, späterer Gründer der Carolina Graz, wurde wegen der Ablehnung eines Duells mit einem Schlagenden unehrenhaft aus der kaiserlichen Armee entlassen, und dies war kein Einzelfall. Dennoch gelang es der Austria, binnen sechs Jahren zur größten Verbindung Innsbrucks zu werden. Die Austria bildete 1866 etwa den dritten Zug der Akademischen Legion (Studentenkompanie) im Krieg gegen Italien. Zugsführer war der Gründer der Austria, Franz Xaver Schedle! Die Fahne der Studentenkompanie hängt heute in einem Schaukasten bei der Aula der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck. In dieser Aula prangert übrigens auch an der Strinseite des Saales unser Wahlspruch! Damals wie heute lauteten die Prinzipien: RELIGIO, das Bekenntnis zur Römisch-Katholischen Kirche PATRIA, Heimatliebe und Bekenntnis zum Vaterland Österreich SCIENTIA, akademische und persönliche Weiterbildung AMICITIA, Brüderlichkeit und Freundschaft Mehr über unsere 4 Prinzipien erfährst Du unter "Prinzipien". -

Schon Zeus Liebte Europa (PDF

7 1 Herausgeber: Verein zur Dokumentation der Zeitgeschichte 3970 Weitra, Rathausplatz 1 Eigentümer und Verleger: Vytconsult GmbH 2514 Traiskirchen, Karl Hilberstraße 3 2 „Noch nie hat es eine so lange Zeit des friedlichen Zu- sammenlebens am europäischen Kontinent gegeben. Der Integrationsprozess ist weit fortgeschritten, aber noch nicht unumkehrbar.“ Alois Mock im Jahr 2000 ÖVP-Bundesparteiobmann (1979 - 1989), Vizekanzler (1987 - 1989) und Außenminister (1987 - 1995) 3 Inhaltlicher Leitfaden Der Ursprung Europas ....................................................................5 Die Geschichte des europäischen Einigungswerkes .................................9 Die Gründung der Montanunion ...................................................... 13 Die Geburtsstunde der EWG .......................................................... 15 Österreich setzt auf Kurs Richtung Brüssel ........................................ 19 Fall des Eisernen Vorhangs ........................................................... 22 Aus der EG wird die EU Start der Beitrittsverhandlungen .................................................... 24 Chronik der EU von 1995-2019 ....................................................... 26 Quo Vadis, EU ........................................................................... 39 Sebastian Kurz ................................................................ 41 Othmar Karas .................................................................. 44 Johannes Hahn ............................................................... -

Wolfgang Schüssel – Bundeskanzler Regierungsstil Und Führungsverhalten“

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit: „Wolfgang Schüssel – Bundeskanzler Regierungsstil und Führungsverhalten“ Wahrnehmungen, Sichtweisen und Attributionen des inneren Führungszirkels der Österreichischen Volkspartei Verfasser: Mag. Martin Prikoszovich angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 300 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Politikwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Doz. Dr. Johann Wimmer Persönliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit, dass ich die vorliegende schriftliche Arbeit selbstständig verfertigt habe und dass die verwendete Literatur bzw. die verwendeten Quellen von mir korrekt und in nachprüfbarer Weise zitiert worden sind. Mir ist bewusst, dass ich bei einem Verstoß gegen diese Regeln mit Konsequenzen zu rechnen habe. Mag. Martin Prikoszovich Wien, am __________ ______________________________ Datum Unterschrift 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Danksagung 5 2 Einleitung 6 2.1 Gegenstand der Arbeit 6 2.2. Wissenschaftliches Erkenntnisinteresse und zentrale Forschungsfrage 7 3 Politische Führung im geschichtlichen Kontext 8 3.1 Antike (Platon, Aristoteles, Demosthenes) 9 3.2 Niccolò Machiavelli 10 4 Strukturmerkmale des Regierens 10 4.1 Verhandlungs- und Wettbewerbsdemokratie 12 4.2 Konsensdemokratie/Konkordanzdemokratie/Proporzdemokratie 15 4.3 Konfliktdemokratie/Konkurrenzdemokratie 16 4.4 Kanzlerdemokratie 18 4.4.1 Bundeskanzler Deutschland vs. Bundeskanzler Österreich 18 4.4.1.1 Der österreichische Bundeskanzler 18 4.4.1.2. Der Bundeskanzler in Deutschland 19 4.5 Parteiendemokratie 21 4.6 Koalitionsdemokratie 23 4.7 Mediendemokratie 23 5 Politische Führung und Regierungsstil 26 5.1 Zusammenfassung und Ausblick 35 6 Die Österreichische Volkspartei 35 6.1 Die Struktur der ÖVP 36 6.1.1. Der Wirtschaftsbund 37 6.1.2. -

Global Austria Austria’S Place in Europe and the World

Global Austria Austria’s Place in Europe and the World Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.) Anton Pelinka, Alexander Smith, Guest Editors CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | Volume 20 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2011 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, ED 210, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Book design: Lindsay Maples Cover cartoon by Ironimus (1992) provided by the archives of Die Presse in Vienna and permission to publish granted by Gustav Peichl. Published in North America by Published in Europe by University of New Orleans Press Innsbruck University Press ISBN 978-1-60801-062-2 ISBN 978-3-9028112-0-2 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Bill Lavender Lindsay Maples University of New Orleans University of New Orleans Executive Editors Klaus Frantz, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Helmut Konrad Universität Graz Universität -

And Gyula Horn (Hungary)

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified June 26, 1989 Memorandum of Conversation Foreign Ministers Alois Mock (Austria) and Gyula Horn (Hungary) Citation: “Memorandum of Conversation Foreign Ministers Alois Mock (Austria) and Gyula Horn (Hungary),” June 26, 1989, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, ÖStA, AdR, II-Pol 1989, GZ. 222.18.23/35-II.SL/89. Obtained and translated by Michael Gehler and Maximilian Graf. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/165709 Summary: Transcript of official visit between Foreign Minister Horn (Hungary) with Foreign Minister Mock (Austria). In it they discuss Western European integration including Hungary's participation, the Europe Free Trade Agreement, and Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. They continue with the development of Eastern Europe elaborating the developments with the Warsaw Pact, Hungarian/USSR relations, reforming Hungarian policy, and Austria's place in these changing times. Original Language: German Contents: English Translation German Transcription Official visit by Foreign Minister Horn; Conversation with Foreign Minister Mock, 26 June 1989; International Issues International issues were discussed during the working breakfast and the work meeting on 26.6.1989. The following topics were broached: l. West European Integration: 1.1 Hungarian participation: For Foreign Minister Horn,[1] European integration processes have come about through “objective reasons.” He was concerned about the risk of walling off the outside, above all from the side of the EC.[2] However, within the 12 EC states there is no uniform attitude to non-members, above all to Eastern Europe. Hungary aspires in the short-term for an agreement on tariff preferences with the EC, similar to that of Yugoslavia,[3] and in the medium-term a genuine free trade agreement (This would require a prior liberalization of the Hungarian economic order and the convertibility of the Forint). -

Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Ac 2O Cia Has No Objection

UNCLASSIFIED DOCUMENT ID: 26483367 INQNO: DOC6D 00238008 DOCNO: TEL 009813 87 PRODUCER: VIENNA SOURCE: STATE DOCTYPE: IN DOR: 19870706 TOR: 151708 DOCPREC: P ORIGDATE: 198707061633 MHFNO: 87 5366694 DOCCLASS: U HEADER PP RUEAIIB ZNR UUUUU ZOC STATE ZZH STU8531 PP RUEHC DE RUFHVI #9813/01 1871637 ZNR UUUUU ZZH P 061633Z JUL 87 FM AMEMBASSY VIENNA TO RUEHC/SECSTATE WASHDC PRIORITY 4678 INFO RUEHDC/USDOC WASHDC RUEBWJA/DEPT OF JUSTICE WASHDC RUEHIA/USIA WASHDC 3316 RUEHAM/AMEMBASSY AMMAN 100,3 RUFHOL/AMEMBASSY BONN 6405 RUFHTV/AMEMBASSY TEL AVIV 3578 RUDKRW/AMEMBASSY WARSAW 9566 DECLASSIFIED AND RELEASED BY RUDKDA/AMEMBASSY BUDAPEST 3410 CENTRAL INT ELLIGENCE AGENCY RUEHPG/AMEMBASSY PRAGUE 9751 SOURCESME1HOOSEXEMPTI0N3828 RUFHRN/AMEMBASSY BERN 5126 NAZI RUEHDT/USMISSION USUN NEW YORK 0367 WAR CRIAESDISCLOSOREACT RUFHMB/USMISSION USVIENNA 0253 DAU 2001 2007 BT CONTROLS UNCLAS VIENNA 09813 USVIENNA FOR MBFR AND UNVIE STATE FOR EUR/CE, INR/WEA AND INR/P USIA FOR EU USDOC FOR IEP/EUR OWE FOR P. COMBE JUSTICE FOR KORTEN AND SHER E.O. 12356: N/A TEXT TAGS: PREL, PGOV, ELAB, PARM, PHUM, AU SUBJECT: AUSTRIAN PRESS SUMMARY NO.121/87, FOR 07/06/87 1. FM MOCK ON INDEPENDENCE DAY RECEPTION: NAZI WAR CRIMES DISCLOSURE AC 2O IN REGARD TO THE ABSENCE OF THE AMERICAN AMBASSADOR FROM OFFICIAL DIPLOMATIC EVENTS FOR PRESIDENT WALDHEIM IN CIA HAS NO OBJECTION TO DECLASSIFICATION AND/OR RELEASE OF CIA INFORMATION IN MIS DOCUMENT UNCLASSIFIED Page 1 UNCLASSIFIED JORDAN, FM ALOIS MOCK STRESSED THAT THE "AUSTRIANS WILL BE ABLE TO DEMONSTRATE AT THE AMERICAN EMBASSYS INDEPENDENCE DAY RECEPTION IN VIENNA THAT THEY ALSO DO NOT GO EVERYWHERE". -

CONTENT Foreword

5 CONTENT Foreword . 15 I . Starting Situation: World War I, End of the Monarchy, Founding of the Republic of Austria, and the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1914–19 . 21 1. The Abdication of the Kaiser, “Republic of German-Austria”, Prohibition against the Anschluss, and the Founding of a State against Its Will 1918–19 21 2. On the Eve of Catastrophe ..................................... 28 3. The Summer of 1914 and Deeper-seated Causes ................... 30 4. World War I Sees No Victors .................................. 33 5. Dictates as Peace Agreements .................................. 40 6. Paris and the Consequences ................................... 43 7. A Fragmented Collection of States as a Consequence of the Collapse of the Four Great Empires ......................................... 47 8. Societal Breaks: The Century of European Emigration Ends and the Colonies Report Back for the First Time ................................. 53 9. A World in Change against the Background of Europe Depriving Itself of Power: The Rise of the US and Soviet Russia More as an Eastern Peripheral Power 55 10. Interim Conclusion .......................................... 59 II . A Lost Cause: Austria between Central Europe, Paneuropean Dreams, the “Anschluss” to Nazi Germany and in Exile Abroad 1918/19–45 63 1. The End of the European Great Powers and a Man with His Vision .... 63 2. The Unwanted State: Austria’s Reorientation in the Wake of the Paris Postwar Order 1919–21 .............................................. 69 3. Ignaz Seipel as a Political Key Figure and the Geneva League of Nations Loan 1922 ................................................. 75 4. The Paneuropean Dream and Central Europe Idea as Visions between Broad- reaching Dependence and the Brief Attainment of Sovereignty 1923–30 80 5. -

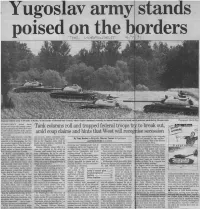

Yugoslav Army Stands Poised on the Borders

Yugoslav army stands poised on the t orders Yugoslav federal army T-55 tanks at Krsko, on the border of Slovenia and Croatia, where clashes continued yesterday as federal troops tried to break out of positions encircled by Slovene units Photograph: David Rose YUGOSLAVIA'S armed forces fanned out across the country yester- day in preparation for what their chief Tank columns roll and trapped federal troops try to break out, of staff called a decisive strike against the secessionist republics of Slovenia amid coup claims and hints that West will recognise secession and Croatia. Late last night, however, some Slo- and Croatia, clashes continued near column approaching from Belgrade. vene fighters and federal troops were the border separating the two repub- By Tony Barber in Belgrade, Marcus Tanner in Ljubljana They are massing on our borders," reported to be disengaging, but Slo- lics as the Yugoslav army tried to and Sarah Helm in London s aid Janez Slapar, chief of the Slovene vene leaders suggested the army might break out of positions encircled by territorial Defence force. be regrouping for a "brutal assault". Slovene defence units. eral army was "running amok" and, in tween Serbs, Croats and Muslim Slavs, Across the border in Croatia, mem- Radio reports said some federal units Slovene officials, whose offer of a a telephone call to the Yugoslav lead- The third unit went in the middle, ers of that republic's National Guard poised earlier to thrust into Slovenia truce was rejected by the army oin er, Stipe Mesic, repeated Bonn's de- north-west toward Slovenia, i jeans and flak jackets and carrying were heading south into Croatia. -

„Greater Europe“ Am Sprung in Die 3. Dekade Rückblick Und Perspektive 2 HENKEL-LIFE SPEZIAL | 01/2009 1989-2009: 20 Jahre Ostöffnung

Österreich Henkel-Life1989-2009: 20 Jahre Ostöffnung Spezialausgabe I 01/2009 | www.henkel.at Michael Spindelegger Friedrich Stara Alois Mock ...über die Zukunft Europas ...über das Henkel-Erfolgsgeheimis ...über das Wunder von 1989 | Seite 3 | Seite 10 | Seite 15 20 Jahre Ostöffnung „Greater Europe“ am Sprung in die 3. Dekade Rückblick und Perspektive 2 HENKEL-LIFE SPEZIAL | 01/2009 1989-2009: 20 Jahre Ostöffnung Editorial Am Beginn der 3. Dekade nach der Ostöffnung Günter Thumser, Henkel CEE-Präsident 2009 wird das Jubiläum Ebenfalls neu am Beginn der 3. Dekade: In Osteuropa reift eine „20 Jahre Ostöffnung“ began- ehrgeizige, junge, sehr gut ausgebildete Generation heran, die gen. Für Österreichs Wirtschaft die Zeit des „Eisernen Vorhangs“ nur mehr aus Geschichts- bedeutete 1989 und das damit büchern kennt. Sie will und wird ihre Zukunft eigenständig, verbundene historische Ereignis aktiv gestalten – mit Konsequenz nicht nur für die lokalen Ar- eine einmalige Chance, die ge- beitsmärkte, sondern auch mit berechtigtem Blick auf Schlüssel- nutzt wurde. Das gilt auch für positionen, die in Unternehmen im Westen zu besetzen sind. Henkel in Wien. Damals lag der Fokus auf Österreich. Der Um- Was bedeutet dies für die Politik in Österreich? satz belief sich auf umgerechnet 122 Mio. Euro. Heute ist die in Wien ansässige Henkel CEE in Das Bildungssystem bedarf einer Reform, die sicherstellt, dass 32 Ländern der Region tätig. Sie beschäftigt 10.000 Mitarbeiter die Leistungsbereitschaft von Lehrenden und Lernenden glei- und steht für einen Umsatz von rund 2,5 Mrd. Euro. chermaßen gefördert wird. Selbstständigkeit, individuelle Ta- lente müssen unterstützt werden, die Offenheit für neue Inhal- Die ersten expansiven Schritte in der anfänglichen Pionierphase te gegeben sein. -

IFLA International Newspaper Conference

IFLA International Newspaper Conference “Newspaper Digitization and Preservation. New prospects. Stakeholders, Practices, Users and Business Models” 11-13 April 2012 BnF, Paris With the support of: Archiving the Press Photo at the National Library of Austria Hans Petschar [email protected] Ifla International Newspaper Conference Paris 11-13 April 2012 2 Press Photography – Tour d‘histoire • Habsburg Monarchy • First World War • First Republic • „Anschluss“ & National Socialism • Liberation and Marshall Plan • Photographer‘s Archives • Co-operation Austrian Press Agency – Austrian National Library 3 Habsburg Monarchy • Emperor Franz Joseph • Sarajewo 1910 4 Emperor Francis Joseph on his tour to Bosnia 1910: the Emperor leaving the government building in Sarajevo. Heinrich Schuhmann 31.05.1910 5 Emperor Francis Joseph on his tour to Bosnia 1910: the Emperor on the Roman Bridge in Mostar Atelier Fachet 03.06.1910 6 Emperor Francis Joseph with Archduke Otto Hermann Kosel 15.09.1914 7 Kriegspressequartier • War Photography • War Press office From 1914 to 1918 the “Kriegspressequartier” produced more than 50.000 photographic documents covering the eastern and southern front. 8 First World War: Patrol at the Carinthian Front 1916/1917 Kriegspressequartier 9 First World War, Carinthian Front 1916/1917 (Rattendorfer Alpe). Shelter for cannons. Kriegspressequartier 10 Erste Repuplik • Österreichische Lichtbildstelle In the 1920’s and 1930’s the Lichtbildstelle documented events, people, places and every day life in the First Republic. 11 Proclamation of the Austrian republic Österreichische Lichtbildstelle ???? 12.11. 1918 12 Gypsie’s hovel in Dobersdorf (Burgenland). 13 Österreichische Lichtbildstelle ???? Ca. 1925 July Revolt Phot.: Lothar Rübelt 14 15.07. 1927 Unemployed Phot.: Albert Hilscher ca. -

Online Zu Gott

Ein kleiner Wien 1080 , Lerchenfelder 14, Str. STICH für mich, ACADEMIA Politik. Wirtschaft. Religion. Kultur. 7 Eucharistie am Schirm: ein wichtiger Kirche im Krisenmodus 14 für uns Uni und Covid: alle. ein sozialer Härtefall 21 ÖCV-Bildungsakademie: Erfolgsmodell wird 50 3,00 Jahrgang (AT), 72. | Erscheinungsort: Wien. Österreichische Post M | AG. MZ 02Z030510 € Preis: ONLINE ZU GOTT Wir unterstützen: Wie digital darf/muss Kirche sein? Melden Sie sich für die Corona-Schutzimpfung an. Und unterstützen Sie auch andere Menschen dabei. Weitere Infos zur Corona-Schutzimpfung auf www.uniqa.at Gemeinsam besser leben. Österreichischer Cartellverband 03 | 2021 (Mai) 0259_21_MSY_Inserat_Pflaster_210x280abf.indd 1 01.03.21 11:07 KIRCHE ONLINE Ein Jahr ACADEMIA um 15 Euro Das Jahres-Abo im Umfang von sechs Ausgaben kostet nur 4 7 15 Euro und kann per E-Mail an [email protected] oder per Telefon unter +43-1-405 16 22 31 bestellt werden. Es ge- IHRE STORY IST DIE IHR SOLLT FLEISSIG nügt auch einfach eine Überweisung des Abonnement-Prei- FROHBOTSCHAFT ZUSAMMENKOMMEN ses auf das Konto AT11 3200 0002 1014 5050 (Academia) Wilhelm Ortmayr Lucas Semmelmeyer unter Angabe der Zustelladresse. 14 16 18 11 INFANTILISIERUNG, DREI SEMESTER CHEMISCHE SYNTHESEN? „WIENER ZEITUNG“ DEPRESSIONEN, NOTFALL-MODUS NICHT IM HOME-OFFICE Engelbert Washietl SELBSTMORDE Christoph Riess Lucas Semmelmeyer Léopold Bouchard 21 26 29 24 2+2 = … „BEMERKENSWERTE PREMIERE VON THEOLYMPIA 50 JAHRE LANG MODERN … EIN ANWENDUNGSBEISPIEL BEMÜHUNGEN“ Marie-Theres Igrec, Florian Tursky FÜR EINE ADDITION Gerhard Hartmann Lucas Semmelmeyer Wolfram Kreipl 10 / 33 32 34 37 REZENSIONEN EIN SCHRITT ZUR ES GILT DIE LÖSUNGSBEGABUNG PICKELHAUBE UNSCHULDSVERMUTUNG Franz Mayrhofer Gerhard Hartmann Herbert Kaspar 38 LESERBRIEFE OFFENLEGUNG Medieninhaber: Cartellverband der katholischen österreichischen Studentenverbindungen (ÖCV). -

Confidential: for Review Only

BMJ Confidential: For Review Only Does the stress of politics kill? An observational study comparing premature mortality of elected leaders to runner-ups in national elections of 8 countries Journal: BMJ Manuscript ID BMJ.2015.029691 Article Type: Christmas BMJ Journal: BMJ Date Submitted by the Author: 02-Oct-2015 Complete List of Authors: Abola, Matthew; Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Olenski, Andrew; Harvard Medical School, Health Care Policy Jena, Anupam; Harvard Medical School, Health Care Policy Keywords: premature mortality, politics https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/bmj Page 1 of 46 BMJ 1 2 3 Does the stress of politics kill? An observational study comparing accelerated 4 5 6 mortality of elected leaders to runners-up in national elections of 17 countries 7 8 Confidential: For Review Only 9 10 1 2 3 11 Andrew R. Olenski, B.A., Matthew V. Abola, B.A., , Anupam B. Jena, M.D, Ph.D. 12 13 14 15 1 Research assistant, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 16 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115. Email: [email protected] . 17 18 2 19 Medical student, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, 2109 Adelbert 20 Rd., Cleveland, OH 44106. Phone: 216-286-4923; Email: [email protected]. 21 22 3 Associate Professor, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 23 24 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115; Tel: 617-432-8322; Department of Medicine, 25 Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; and National Bureau of Economic 26 Research, Cambridge, MA. Email: [email protected]. 27 28 29 30 31 Corresponding author from which reprints should be requested: 32 33 Anupam Jena, M.D., Ph.D.