Voluntary Collective Isolation As a Best Response to COVID-19 for Indigenous 4 Populations? a Case Study and Protocol from the Bolivian Amazon 5 6 Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

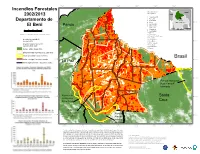

Incendios Forestales 2002/2013 Departamento De El Beni

68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 62°W Incendios Forestales municipalidades/ Brazil municipalities Peru 2002/2013 1 Guayaramerín 2 Riberalta 3 Santa Rosa El Beni Departamento de 11°S 4 Reyes B O L I V I A 11°S 5 San Joaquín Pando 6 Puerto Siles El Beni 1 7 Exaltacion Paraguay 0 25 50 75 100 2 8 Magdalena Chile Argentina Km 9 San Ramón 10 Baures escala 1/4.100.000,Lamber Conformal Conic 11 Huacaraje 12 Santa Ana de Yacuma 13 San Javier incendio forestal 2013/ 14 San Ignacio 12°S hot pixel 2013 15 San Borja 12°S 16 Rurrenabaque incendio forestal 2002-2012/ 17 Trinidad hot pixel 2002-2012 18 San Andrés 6 19 Loreto bosque 2005 / forest 2005 población indígena/indigenous settlement 7 areas protegidas / protected area 8 Brasil limite municipal / municipal border 13°S 5 13°S limite departamental / regional boundary La Paz 4 3 9 10 11 14°S 14°S 1 Parque Nacional Noel Kempff 12 13 Mercado 16 17 15°S Reserva de 15 Santa 15°S la Biosfera Pilon Lajas Cruz 14 19 18 Reserva de la Biosfera Parque 16°S 16°S del Beni Nacional Isiboro Secure 68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 62°W 61°W *Cada incendio forestal representa el punto central de un píxel 1km2 de MODIS, por lo que el incendio detectado se puede situar en cualquier lugar dentro del área de 1km2. Si el punto central del pixel (y por tanto el lugar del incendio reportado) está dentro del bosque, pero a menos de 500m de la frontera forestal, existe la posibilidad de que el incendio haya ocurrido realmente fuera del bosque a lo largo de Fuente de Datos: Cobertura Forestal ~1990~2005 (Conservation International) la frontera forestal. -

Project Document

DEVELOPMENT BANK OF LATIN AMERICA (CAF) PROJECT DOCUMENT FOR A GRANT FROM THE GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY TRUST FUND OF USD 10.1 MILLION TO THE MINISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER OF BOLIVIA FOR THE PROJECT AMAZON SUSTAINABLE LANDSCAPE APPROACH IN THE NATIONAL SYSTEM OF PROTECTED AREAS AND STRATEGIC ECOSYSTEMS OF BOLIVIA (INTEGRATED PROJECT AS PART OF THE AMAZON SUSTAINABLE LANDSCAPES 2 SFM IMPACT PROGRAM) Revised 19 April 2021 EQUIVALENT VALUE (Official exchange rate as at 2 March 2020; source: BCB) 6.86 bolivianos (BOB) = 1 US dollar (USD) FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ASL Amazon Sustainable Landscapes Pilot Program – Programa Piloto de Impacto Territorios Sostenibles Amazónicos (GEF-6) ASL2 Amazon Sustainable Landscapes Program, Phase II – Programa de Impacto Territorios Sostenibles Amazónicos, Fase II (GEF-7) BCB Banco Central de Bolivia – Central Bank of Bolivia BOB Bolivian, currency – Boliviano, moneda C Carbon – Carbono CO2 Carbon dioxide – dióxido de carbono CAF Development Bank of Latin America – Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina; Corporación Andina de Fomento CIPOAP Association of Indigenous Amazonian Peoples of Pando – Central Indígena de Pueblos Originarios Amazónicos de Pando CNAMIB National Confederation of Indigenous Women of Bolivia – Confederación Nacional de Mujeres Indígenas de Bolivia CO2 Carbon dioxide – Dióxido de carbono CBO/OCB community-based organisation – organización comunitaria de base DGBAP General Directorate of Biodiversity and Protected Areas – Dirección General -

Bolivia Rapid Response Floods

RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS BOLIVIA RAPID RESPONSE FLOODS RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Ms. Katherine Grigsby REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. There were two events that brought significant inputs to the CERF implementation review: the first one was a lessons learned workshop held in 25t and 26t August 2014. It took place in El Beni with the participation of 57 people representing more than 40 humanitarian partners, municipal, departmental and national government authorities. The second event formally designated as the AAR took place on 17t December 2014 with the participation of UN implementing Agencies and their field partners in the framework of the HCT. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES NO This report was prepared with the active participation of the RC/HC and the HCT. c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES NO The dissemination of the final version of the RC/HC report will start in parallel with the submission to the CERF Secretariat 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT TABLE 1: EMERGENCY -

WFP Humanitarian Response

Bolivia Floods Bulletin N° 8 May 9th, 2014 WFP response in numbers Highlights of the emergency N° affected people 325.000 √ In San Borja, 950 families have started to work on early rehabilitation of their assets under the N° people assisted 11.535 “food for work” modality: housing reconstruction, land rehabilitation for production and construc- tion of communal gardens. N° municipalities assisted 8 √ Fluvial transport suppliers are not available in Be- N° communities assisted 147 ni to transport food at the moment, as they are busy saving and transporting cattle. N° family rations distributed 37.835 √ Water continues to get down in Guayaramerín, N° metric tones of food distribu- 56,6 approximately 1 meter, and affected communi- ted ties have started to work on the reconstruction of their houses. Resourcing update Planned distribution Warehouse Municipalities People Needs 4.000.000 USD (8-14 May) (comunidades) Trinidad San Ignacio, Loreto, 23.600 Confirmed contributions: Santa Ana, San 100.000 USD Italy Ramón, San Joaquín, 869.436 USD CERF Puerto Siles, Exalta- 103.250 USD CERF Log ción, Trinidad 1.200.000 USD WFP SRAC Riberalta Guayaramerín, Ribe- 18.585 ralta, San Lorenzo, 200 USD Andean Valley Gonzalo Moreno, San Gap 1.727.114 USD Pedro, Villanueva Total 42.185 * 1.374.818 USD WFP loan to be returned. CONTACTS Paolo Mattei, Country director: [email protected] +591-72007545 Sergio Alves, emergencies: [email protected] +591-70130266 WFP humanitarian response Operational √ Given the unavailability of fluvial √ A total of 38,4 MT of food was delivered transport suppliers in Beni, WFP and to 6.775 personas en 54 communities of VIDECI coordinate the transport of food Trinidad, San Ignacio de Moxos and San from Trinidad to different destinations. -

Distribution, Diversity and Conservation Status of Bolivian Amphibians

Distribution, diversity and conservation status of Bolivian Amphibians Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrichs-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von Steffen Reichle aus Stuttgart Bonn, 2006 Diese Arbeit wurde angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch- Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität Bonn. 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. W. Böhme 2. Referent: Prof. Dr. G. Kneitz Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 27. Februar 2007 "Diese Dissertation ist auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn http://hss.ulb.uni- bonn.de/diss_online elektronisch publiziert" Erscheinungsjahr: 2007 CONTENTS Acknowledgements I Introduction 1. Bolivian Amphibians 1 2. Conservation problems of Neotropical Amphibians 2 3. Study area 3 3.1 Bolivia – general data 3 3.2 Ecoregions 4 3.3 Political and legal framework 6 3.3.1 Protected Areas 6 II Methodology 1. Collection data and collection localities 11 2. Fieldwork 12 2.1 Preparation of voucher specimens 13 3. Bioacustics 13 3.1 Recording in the field 13 3.2 Digitalization of calls, analysis and visual presentation 13 3.3 Call descriptions 13 4. Species distribution modeling – BIOM software 14 4.1 Potential species distribution 14 4.2 Diversity pattern and endemism richness 14 5. Assessment of the conservation status 14 5.1 Distribution 15 5.2 Taxonomic stability 15 5.3 Presence in Protected Area (PA) 15 5.4 Habitat condition and habitat conversion 16 5.5 Human use of the species 16 5.6 Altitudinal distribution and taxonomic group 16 5.7 Breeding in captivity 17 5.8 Conservation status index and IUCN classification 17 III Results 1. -

BO-Plan Indígena Covid19-Beni, Julio 2020.Pdf

GOBIERNO AUTÓNOMO DEPARTAMENTAL DEL BENI SECRETARÍA DEPARTAMENTAL DE DESARROLLO INDÍGENA GOBIERNO AUTÓNOMO DEPARTAMENTAL DEL BENI SECRETARÍA DEPARTAMENTAL DE DESARROLLO INDÍGENA PLAN DE ACCIÓN “FORTALECIMIENTO DEL SISTEMA SANITARIO EN PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS ORIGINARIOS CAMPESINOS, PARA LA DEFENSA Y PROTECCIÓN DE SUS DERECHOS A LA SALUD, CON ÉNFASIS EN COVID-19, EN EL DEPARTAMENTO DEL BENI” SANTÍSIMA TRINIDAD – BENI - BOLIVIA 2020 GOBIERNO AUTÓNOMO DEPARTAMENTAL DEL BENI SECRETARÍA DEPARTAMENTAL DE DESARROLLO INDÍGENA ÍNDICE 1. INTRODUCCIÓN. ............................................................................................................... 1 2. MARCO LEGAL. ................................................................................................................ 2 3. ANTECEDENTES. ............................................................................................................. 5 4. OBJETIVOS. ...................................................................................................................... 6 4.1. Objetivo general. ............................................................................................................. 6 4.2. Objetivos específicos. ...................................................................................................... 6 5. ESTRATEGIAS DE INTERVENCIÓN ................................................................................ 7 6. METODOLOGÍA APLICADA. ............................................................................................ 7 6.1. Logística. -

A Case Study in Development from the Cattle Region

CONFLICT BETWEEN WHITES AND INDIANS ON THE LLANOS DEPARTMENT: A CASE STUDY IN DEVELOPMENT DE MOXOS , BENI FROM THE CATTLE REGIONS OF THE BOLIVIAN ORIENTE By JAMES C. JONES DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF A FULFILLMENT THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1980 To Ignacianos and other Peasants of the Bolivian Oriente. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many institutions and individuals, both in Bolivia and in the United States, contributed to make this study possible. Owing to the sensitivity of some of the material presented, however, the names of certain helpful Bolivians and Bolivian agencies must remain anonymous to assure their welfare. This is made especially necessary by the severe government retaliation against and repression of dissent that currently obtains in that country. Certainly the author's first debt of thanks in Bolivia goes to the Ignacianos, without whose intimate collaboration this study could not have been achieved. The story told in the pages to follow is their story in particular, but it is in a more general way also the story of all peasants of the Beni Department. Moving closer to home, the author tenders warm thanks and to Professor Wagley, chairman of his doctoral committee, Bernard, to Professors Solon Kimball, Maxine Margolis, Russell doctoral and David Bushnell for their guidance through the program and especially for their suggestions for improvement be remembered of the manuscript. Professor Wagley will always affectionately for his unstinting moral support throughout. The research reported herein was financed by three after institutions. The project was conceived and designed m a summer's preliminary reconnaissance of the Beni Department made possible by a grant from University of Florida Founda- tion Tropical South America Program. -

Bolivia: Floods and Landslides

Emergency appeal MDRBO006 Bolivia: floods and GLIDE n° FL-2011-000020-BOL 08 March 2011 landslides This Emergency Appeal seeks 518,725 Swiss francs in cash, kind, or services to support the Bolivian Red Cross to assist 2,500 beneficiaries for 6 months, and will be completed by the end of August 2011. A Final report will be made available by 1 December 2011 (three months after the end of the operation). On 3 March, 78,074 Swiss francs were allocated from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support this operation. Un-earmarked funds to replenish DREF are encouraged. Around 14,000 families are affected in Bolivia, particularly in the Department of La Paz where a hillside collapsed in a densely populated area, destroying hundreds of homes. Due to the phenomenon of Source: BRC La Niña, the weather pattern in Bolivia has been disrupted, with drought in late 2010 and early 2011, and many days of intense and constant rains throughout February. These weeks of heavy rain caused floods and mudslides in 9 departments of the country affecting some 14,000 families and causing 56 deaths. Based on the situation, the government of Bolivia declared a state of emergency on 23 February. This Emergency Appeal responds to a request from the Bolivian Red Cross (BRC) and focuses on providing support to make an appropriate and timely response in delivering assistance and relief to 2,500 families (12,500 people) with food and non-food relief items, and 500 families (2,500 people) with emergency health care, water, sanitation and hygiene promotion and early recovery. -

The Bolivian Beef Cattle Industry: Effects of Transportation Projects Upon Plant Location and Product Flows in Beni Luis A

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1981 The Bolivian beef cattle industry: effects of transportation projects upon plant location and product flows in Beni Luis A. Ampuero-Ramos Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, and the Agricultural Economics Commons Recommended Citation Ampuero-Ramos, Luis A., "The Bolivian beef cattle industry: effects of transportation projects upon plant location and product flows in Beni " (1981). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 6869. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/6869 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 8123114 AMPUERO-RAMOS, LUIS A. THE BOLIVIAN BEEF CATTLE INDUSTRY: EFFECTS OF TRANSPORTATION PROJECTS UPON PLANT LOCATION AND PRODUCT FLOWS IN BENI Iowa State University PH.D. 1981 University Microfilms 1n t© r nSt i O n s I 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 The Bolivian beef cattle industry; Effects of transportation projects upon plant location and product flows in Beni by Luis A. Ampuero-Ramos A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department: Economics Major: Agricultural Economics Approved: Signature was redacted for privacy. In Charge /&£ Ma j or Work Signature was redacted for privacy. -

Plan Territorial De Desarrollo Integral Del Municipio De Guayaramerin Para Vivir Bien (Ptdi: 2016 – 2020) 14

PLAN TERRITORIAL DE DESARROLLO INTEGRAL DEL MUNICIPIO DE GUAYARAMERIN PARA VIVIR BIEN (PTDI: 2016 – 2020) 14 Septiembre, 05 de 2016 PARTICIPANTES EN LA ELABORACION DEL PLAN TERRITORIAL DE DESARROLLO INTEGRAL MUNICIPAL DE GUAYARAMERIN (PTDI: 2016-2020) GOBIERNO AUTÓNOMO MUNICIPAL DE GUAYARAMERIN: NOMBRE Y APELLIDOS CARGO Helen Gorayeb Callejas Antelo Alcaldesa Municipal Carmen Justa Terceros Gutiérrez Presidenta Concejo Municipal Jhonny Fernando Cárdenas España Vice Presidente Concejo Municipal Henrry Cabral Atiare Secretario Concejo Municipal Janet Cuéllar Mejía Concejala Municipal Juan Francisco Asbun Suárez Concejal Municipal Jhonny Paul Pinto Phillip Concejal Municipal Cordy Tezalia Jauregui Pinto Concejala Municipal ENTIDAD EJECUTORA: RAPUJUSTINIANO S.R.L. Firma de Auditoría & Consultoría EQUIPO TECNICO MUNICIPAL: La Comisión de Supervisión, Revisión y Apoyo Técnico del presente documento, estuvo integrada por las siguientes personalidades: NOMBRE Y APELLIDOS CARGO Ing. Daniel Mauricio Vaca Heredia Secretario Municipal Técnico de Planificación y Desarrollo Territorial Lic. Jorge Enrique Toledo Cortez Secretario Municipal Administrativo y Financiero. Ing. Raúl Melgar Urresti Secretario Municipal de Desarrollo Humano. Ing. Mayerling Kreidstein Ortiz Supervisora del Servicio. Arq. Raimundo Mahe Noza Comisión de Apoyo Técnico. Ing. Saúl Fabricio Rivero Bollati Comisión de Apoyo Técnico. Lic. Raymundo Freitas Vargas Comisión de Apoyo Técnico. Guayaramerin, Septiembre 05 de 2016 INDICE GENERAL I. ENFOQUE POLÍTICO............................................................................................................................... -

Migration– Climate Change

MIGRATION– CLIMATE CHANGE From a disaster risk management perspective in the municipalities of Bolpebra, San Ignacio de Moxos and Santa Ana del Yacuma The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in the meeting of operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. ______________________ MIGRATION– CLIMATE CHANGE Horacio Calle Publisher: International Organization for Migration Head of Office – IOM 22 Street Calacoto Bldg. Montecristo N.7896 Off.103 Oscar Cabrera La Paz Vice Minister of Civil Defense Bolivia Tel.: +591 2 2770161 Fax.: +591 2 2771972 Technical coordination: Email: [email protected] Liliana Lorini Lázaro – IOM Website: www.iom.int Contents: Fundación el JISUNÚ del Desarrollo _____________________________________________ Content review: Heber Romero Velarde – VIDECI ISBN 978-92-9068-832-7 (PDF) Liliana Lorini Lázaro – IOM © 2020 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

1 Introduction

SUMMARY 1Introduction (1) Background of the Study The Republic of Bolivia is a landlocked country located between 10 degrees and 23 degrees South, has an area of 1,098,581km2 (3 times as large as Japan) with a population of 8,274,225 (Census 2001), and is also known as one of the poorest countries in Latin America. Bolivia continues to promote popular participation and decentralization laws, as it maintains its policies on free economy. The Bolivian government of Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada has launched “Bolivia Plan = Action Plan (1997-2002)” with the purpose to alleviate poverty. In the medical and public health sector, it aims to reduce by half under-five mortality rate and maternal mortality rate, addressing policies on a) introduction of Basic Health Insurance, b) improvement of nutritional status, c) infectious disease control (e.g., Chagas' disease, malaria, tuberculosis). It has target health indexes for the target year 2002 concretely, that is to say, a) reduction of maternal mortality rate (50% reduction of 1997's rate of 390/100,000), b) reduction of under- five's mortality rate (50% reduction of 1997's rate of 105/1,000), c) improvement of nutritional status of under-three (50% reduction of 1997's number of 208,000 persons), d) improvement of accessibility to health unit (from 1997's rate of 34% to 85%), e) improvement of immunization status of under-five (from 1997's rate of 85% to 90%), f) reduction of infection rate of malaria (from 1997's rate of 35/1,000 to 8/1,000). Beni Department occupies 213,000km2, 20% of the nation’s total land, and has approximately 365,000 people (2001 Census) that account for the second lowest population density in the country.