A Case Study in Development from the Cattle Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

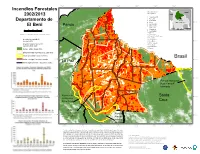

Incendios Forestales 2002/2013 Departamento De El Beni

68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 62°W Incendios Forestales municipalidades/ Brazil municipalities Peru 2002/2013 1 Guayaramerín 2 Riberalta 3 Santa Rosa El Beni Departamento de 11°S 4 Reyes B O L I V I A 11°S 5 San Joaquín Pando 6 Puerto Siles El Beni 1 7 Exaltacion Paraguay 0 25 50 75 100 2 8 Magdalena Chile Argentina Km 9 San Ramón 10 Baures escala 1/4.100.000,Lamber Conformal Conic 11 Huacaraje 12 Santa Ana de Yacuma 13 San Javier incendio forestal 2013/ 14 San Ignacio 12°S hot pixel 2013 15 San Borja 12°S 16 Rurrenabaque incendio forestal 2002-2012/ 17 Trinidad hot pixel 2002-2012 18 San Andrés 6 19 Loreto bosque 2005 / forest 2005 población indígena/indigenous settlement 7 areas protegidas / protected area 8 Brasil limite municipal / municipal border 13°S 5 13°S limite departamental / regional boundary La Paz 4 3 9 10 11 14°S 14°S 1 Parque Nacional Noel Kempff 12 13 Mercado 16 17 15°S Reserva de 15 Santa 15°S la Biosfera Pilon Lajas Cruz 14 19 18 Reserva de la Biosfera Parque 16°S 16°S del Beni Nacional Isiboro Secure 68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 62°W 61°W *Cada incendio forestal representa el punto central de un píxel 1km2 de MODIS, por lo que el incendio detectado se puede situar en cualquier lugar dentro del área de 1km2. Si el punto central del pixel (y por tanto el lugar del incendio reportado) está dentro del bosque, pero a menos de 500m de la frontera forestal, existe la posibilidad de que el incendio haya ocurrido realmente fuera del bosque a lo largo de Fuente de Datos: Cobertura Forestal ~1990~2005 (Conservation International) la frontera forestal. -

From “Invisible Natives” to an “Irruption of Indigenous Identity”? Two Decades of Change Among the Tacana in the Northern Bolivian Amazon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Sondra Wentzel provided by Institutional Repository of the Ibero-American Institute, Berlin From “invisible natives” to an “irruption of indigenous identity”? Two decades of change among the Tacana in the northern Bolivian Amazon “Al final nos dimos cuenta todos que éramos tacanas” (Tacana leader 2001, quoted in Herrera 2009: 1). 1. Introduction: The Tacana In the mid 1980s, a time of redemocratization and structural adjustment policies in Bolivia, consultations about a region suitable for field research on the situation of indigenous peoples in the context of “Amazonian development” led me to the Province of Iturralde in the lowland north of the Department of La Paz (Figure 1). The culture of its indigenous inhabitants, the Tacana,1 had been documented by German researchers in the early 1950s (Hissink & Hahn 1961; 1984). Also, under the motto La Marcha al Norte, the region was the focus of large infrastructure and agro industrial projects which had already stimulated spontaneous colonization, but local people had little information about these activities nor support to defend their rights and interests. Between 1985 and 1988, I conducted about a year of village level field re- search in the region, mainly in Tumupasa, an ex-Franciscan mission among the Tacana founded in 1713 and transferred to its current location around 1770, San- ta Ana, a mixed community founded in 1971, and 25 de Mayo, a highland colonist cooperative whose members had settled between Tumupasa and Santa Ana from 1979 1 Tacana branch of the Pano-Tacanan language family, whose other current members are the Araona, Cavineño, Ese Ejja, and Reyesano (Maropa). -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title Voluntary collective isolation as a best response to COVID-19 for indigenous populations? A case study and protocol from the Bolivian Amazon. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99b288w4 Journal Lancet (London, England), 395(10238) ISSN 0140-6736 Authors Kaplan, Hillard S Trumble, Benjamin C Stieglitz, Jonathan et al. Publication Date 2020-05-15 DOI 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31104-1 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID- 19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information website. Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content - immediately available in PubMed Central and other publicly funded repositories, such as the WHO COVID database with rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the COVID-19 resource centre remains active. Public Health Voluntary collective isolation as a best response to COVID-19 for indigenous populations? A case study and protocol from the Bolivian Amazon Hillard S Kaplan, Benjamin C Trumble, Jonathan Stieglitz, Roberta Mendez Mamany, Maguin Gutierrez Cayuba, Leonardina Maito Moye, Sarah Alami, Thomas Kraft, Raul Quispe Gutierrez, Juan Copajira Adrian, Randall C Thompson, Gregory S Thomas, David E Michalik, Daniel Eid Rodriguez, Michael D Gurven Indigenous communities worldwide share common features that make them especially vulnerable to the Lancet 2020; 395: 1727–34 complications of and mortality from COVID-19. -

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi No Kumi (Confraria De Misericórdia)

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi no Kumi (Confraria de Misericórdia) Takashi GONOI Professor Emeritus, University of Tokyo Introduction During the 80-year period starting when the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier and his party arrived in Kagoshima in August of 1549 and propagated their Christian teachings until the early 1630s, it is estimated that a total of 760,000 Japanese converted to Chris- tianity. Followers of Christianity were called “kirishitan” in Japanese from the Portu- guese christão. As of January 1614, when the Tokugawa shogunate enacted its prohibi- tion of the religion, kirishitan are estimated to have been 370,000. This corresponds to 2.2% of the estimated population of 17 million of the time (the number of Christians in Japan today is estimated at around 1.1 million with Roman Catholics and Protestants combined, amounting to 0.9% of total population of 127 million). In November 1614, 99 missionaries were expelled from Japan. This was about two-thirds of the total number in the country. The 45 missionaries who stayed behind in hiding engaged in religious in- struction of the remaining kirishitan. The small number of missionaries was assisted by brotherhoods and sodalities, which acted in the missionaries’ place to provide care and guidance to the various kirishitan communities in different parts of Japan. During the two and a half centuries of harsh prohibition of Christianity, the confraria (“brother- hood”, translated as “kumi” in Japanese) played a major role in maintaining the faith of the hidden kirishitan. An overview of the state of the kirishitan faith in premodern Japan will be given in terms of the process of formation of that faith, its actual condition, and the activities of the confraria. -

Apellido Paterno Apellido Materno Nombres Lugar De Origen Lugar De

Apellido Paterno Apellido Materno Nombres Lugar de origen Lugar de destino Sexo Abacay Flores Keila Pilar Santa Cruz Trinidad F Abalos Aban Jerson Sucre Tupiza M Aban Nur de Serrano Gabi Santa Cruz Sucre F Abecia NC Vicente Villazón Tarija M Abrego Camacho Francisco Javier Santa Cruz Puerto Suárez M Abrego Lazo Olga Cochabamba San Borja- Beni F Abularach Vásquez Elida Diana Cochabamba Riberalta F Abularach Vásquez Ericka Daniela Cochabamba Riberalta F Acahuana Paco Neymar Gael Santa Cruz La Paz M Acahuana Paco Mauro Matías Santa Cruz La Paz M Acarapi Higuera Esnayder Santa Cruz Cochabamba M Acarapi Galán Axel Alejandro Potosí Cochabamba M Acarapi Montan Noemi Oruro Cochabamba F Acarapi Leocadia Trinidad Cochabamba F Acebey Diaz Anahi Virginia La Paz Tupiza F Acebo Mezza Jorge Daniel Sucre Yacuiba M Achacollo Jorge Calixto Puerto Rico Oruro M Acho Quispe Carlos Javier Potosí La Paz M Achocalla Chura Bethy Santa Cruz La Paz F Achocalle Flores Santiago Santa Cruz Oruro M Achumiri Alave Pedro La Paz Trinidad M Acosta Guitierrez Wilson Cochabamba Bermejo- Tarija M Acosta Rojas Adela Cochabamba Guayaramerin F Acosta Avendaño Arnoldo Sucre Tarija M Acosta Avendaño Filmo Sucre Tarija M Acosta Vaca Francisco Cochabamba Guayaramerin M Acuña NC Pablo Andres Santa Cruz Camiri M Adrian Sayale Hernan Gualberto Cochabamba Oruro M Adrian Aurelia Trinidad Oruro F Adrián Calderón Israel Santa Cruz La Paz M Aduviri Zevallos Susana Challapata Sucre F Agreda Flores Camila Brenda Warnes Chulumani F Aguada Montero Mara Cochabamba Cobija F Aguada Montero Milenka -

Las Dictaduras En América Latina Y Su Influencia En Los Movimientos De

Revista Ratio Juris Vol. 16 N.º 32, 2021, pp. 17-50 © UNAULA EDITORIAL DICTATORSHIPS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THEIR INFLUENCE OF RIGHT AND LEFT MOVEMENTS SINCE THE 20TH CENTURY* LAS DICTADURAS EN AMÉRICA LATINA Y SU INFLUENCIA EN LOS MOVIMIENTOS DE DERECHA E IZQUIERDA DESDE EL SIGLO xx Juan Carlos Beltrán López José Fernando Valencia Grajales** Mayda Soraya Marín Galeano*** Recibido: 30 de noviembre de 2020 - Aceptado: 30 de mayo de 2021 - Publicado: 30 de junio de 2021 DOI: 10.24142/raju.v16n32a1 * El presente artículo es derivado de la línea Constitucionalismo Crítico y Género que hace parte del programa de investigación con código 2019 29-000029 de la línea denominada Dinámicas Urbano-Regionales, Economía Solidaria y Construcción de Paz Territorial en Antioquia, que a su vez tiene como sublíneas de trabajo las siguientes: Construcción del Sujeto Político, Ciudadanía y Transformación Social; Constitucionalismo Crítico y Género; Globalización, Derechos Humanos y Políticas Públicas, y Conflicto Territorio y Paz e Investigación Formativa. ** Docente investigador Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana (UNAULA); Abogado, Universidad de Antioquia; Politólogo, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Medellín; Especialista en Cultu- ra Política: Pedagogía de los Derechos Humanos, Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana (UNAU- LA); Magíster en Estudios Urbano Regionales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Medellín; estudiante del Doctorado en Conocimiento y Cultura en América Latina, Instituto Pensamiento y Cultura en América Latina, A. C.; editor de la revista Kavilando y Revista Ratio Juris (UNAULA), Medellín, Colombia. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8128-4903; Google Scholar: https://scho- lar.google.es/citations?user=mlzFu8sAAAAJ&hl=es. Correo electrónico: [email protected] *** Directora de la Maestría en Derecho y docente investigadora de la Universidad Católica Luis Amigó, investigadora de la revista Kavilando. -

1 the Rise of Evo Morales Through an Electoral Lens: an Introduction 1

NOTES 1 The Rise of Evo Morales through an Electoral Lens: An Introduction 1. Venezuela 1993 (Carlos Andrés Perez), 2002 (Hugo Chávez), Ecuador 1997 (Abdalá Bucaram), 2000 (Jamil Mahuad), 2004 (Lucio Gutiérrez), Bolivia 2003 (Sánchez de Lozada), 2005 (Carlos Mesa). 2. This claim is relevant to the Bolivian case since a group of scholars, following Gamarra (1997a), have pointed to the hybrid nature of its presidential system, contained in Article 90 of the Constitution, as the major determinant of its relative success. 3. Comparativists have consistently affirmed that the primary role of leg- islatures has been either “neglect and acquiescence or obstructionism” (Morgenstern and Nacif 2002: 7). Moreover, according to the latest Latinobarómetro (2007), the general population in Latin America regards legislatures as one of the most ineffective and one of the least trusted institutions. 4. In light of Article 90 of the Political Constitution of the State, which grants authority to Congress to elect the president in case no candidate receives a majority, Gamarra (1997a; 1997b) called the system “hybrid presidentialism.” Shugart and Carey (1992) followed Gamarra’s concep- tualization while Jones (1995) identified it as a “majority congressional system.” Mayorga (1999) called it “presidencialismo parlamentarizado” (parliamentarized presidentialism). Regardless of the variations in the labels assigned to the Bolivian political system, these scholars agree that it exhibits features of both presidential and parliamentary systems. 5. The double quotient formula was calculated in the following manner: the first quotient, the participation quotient, would be obtained by dividing the total valid votes in a department by the number of seats to be distributed. -

Madera River Infrasturcture Paper

DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION Effects of Energy and Transportation Projects on Soybean Expansion in the Madeira River Basin By: Maria del Carmen Vera-Diaz, John Reid, Britaldo Soares Filho, Robert Kaufmann and Leonardo Fleck Support provided by The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and The United States Agency for International Development Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the United States Agency for International Development. We also thank Marcos Amend and Glenn Switkes for their valuable comments and Cecilia Ayala, Pablo Pacheco, Luis Fernando Figueroa, and Jorge Molina for their data collection support in Bolivia. Thanks to Susan Reid for her revision of the English text. The findings of this study are those of the authors only. 2 Acronyms ANAPO Asociación Nacional de Productores de Oleaginosas CNO Constructora Norberto Odebrecht FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FURNAS Furnas Centrais Elétricas S.A. IBAMA Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis IBGE Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IIRSA The Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America INEI Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (Peru) IPAM Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia ISA Instituto Socioambiental IRN International Rivers Network LEME LEME Engenharia NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration NCAR National Center for Atmospheric Research NCEP National Center for Environmental Modeling PCE Projetos -

Elecciones En América Latina

© 2020, Salvador Romero Ballivián Tribunal Supremo Electoral (TSE) Instituto Internacional para la Democracia y la Asistencia Electoral (IDEA Internacional) Diseño de portada: Rafael Loayza Diseño gráfico: Carmiña Salazar/Comunicación Conceptual TRIBUNAL SUPREMO ELECTORAL Av. Sánchez Lima N° 2482 – Sopocachi, La Paz, Bolivia Teléfono/Fax: 2-424221 2-422338 www.oep.org.bo INSTITUTO INTERNACIONAL PARA LA DEMOCRACIA Y LA ASISTENCIA ELECTORAL (IDEA INTERNACIONAL) IDEA Internacional Programa Bolivia Plaza Humboldt N° 54, Calacoto, La Paz, Bolivia Teléfono/Fax: 2-2775252 International IDEA Strömsborg, SE–103 34 Estocolmo, Suecia Teléfono: +46 8 698 37 00 Correo electrónico: [email protected] Sitio web: https://www.idea.int Primera edición, enero de 2021 Depósito Legal: 4-1-1745-20 ISBN: 978-91-7671-353-2 La versión electrónica de esta publicación está disponible bajo licencia de Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. Para obtener más información sobre esta licencia, consulte el sitio web de Creative Commons: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/3.0/>. La presente publicación ha sido elaborada con el apoyo de la Cooperación para el Desarrollo de la Embajada de Suiza en Bolivia. Su contenido es responsabilidad exclusiva del autor y no necesariamente refleja los puntos de vista del Tribunal Supremo Electoral, IDEA Internacional o de la cooperación involucrada. Las publicaciones del Instituto Internacional para la Democracia y la Asistencia Electoral (IDEA Internacional) son independientes de intereses específicos nacionales o políticos. Las opiniones expresadas en esta publicación no representan necesariamente las opiniones de IDEA Internacional, de su Junta Directiva ni de los Miembros de su Consejo. La Paz, Bolivia Distribución gratuita Índice Prólogo de Kevin Casas-Zamora 7 Introducción 15 I. -

Covid-19 Beni - Bolivia

COVID-19 BENI - BOLIVIA PLAN DE RESPUESTA A EMERGENCIA POR EL COVID-19 Julio de 2020 Índice de contenido Contenido 1. Impacto de la Crisis y consecuencias en las personas 1 2. Prioridades y grupos vulnerables 2 3. Análisis de la situación y las necesidades actuales 7 4. Capacidad de Respuesta Nacional y del EHP 8 5. Brechas 10 6. Análisis Estratégico Sectorial 11 6.1. Marco de vinculación estratégica 11 6.2. Marco estratégico sectorial 15 7. Mecanismos de coordinación 21 Anexos 22 Plan de Respuesta Emergencia COVID-19 en el Beni 1. Impacto de la Crisis y consecuencias en las personas Contexto de la crisis Bolivia es, de 31 países emergentes, el más vulnerable ante el impacto de la epidemia de coronavirus, (Tolosa, 2020), según el ranking de la consultora Oxford Economics1. Respecto a la capacidad del sistema de salud para responder al desafío de la epidemia1, el estudio indica que existen 11 camas de hospital y 16 médicos por cada 100.000 bolivianos; esto significa menos camas que en cualquier otro país latinoamericano, y menos médicos que en la mayoría de ellos; por otra parte, los adultos con más de 670 años de edad es el 4,9% de la población de Bolivia (medio millón de personas), un porcentaje parecido al de otros países de ingresos medio- bajos. Por otra parte, un importante componente de la vulnerabilidad boliviana para resistir y/o hacer frente a esta crisis es la fragilidad del sistema económico y la alta proporción de personas que subsisten en la economía informal, razón por la cual las medidas de restricción de la movilización no pueden mantenerse por periodos prolongados. -

Phd Text 2011 Final Unformatted

Chiquitano and the State Negotiating Identities and Indigenous Territories in Bolivia Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Katinka Weber December 2010 Abstract Chiquitano and the State: Negotiating Identities and Indigenous Territories in Bolivia 2010 by Katinka Weber This thesis analyses how Chiquitano people engage with the state and to what effect, based on ethnographic fieldwork carried out between September 2006 and August 2007 in the Bolivian Concepción, San Javier and Lomerío municipalities, in the eastern Bolivian lowlands. It focuses on the most contentious areas of Chiquitano- state relations, namely the emergence of the Chiquitano social movement, the struggle for territory and territorial autonomy and participation in the local state bureaucracy. While Chiquitano interact with the state in order to protect their socio- cultural communal reproduction, this thesis finds that in many ways the Chiquitano organisation acts as part of the state and replicates its neo-liberal multicultural rhetoric. The state remains the main shaper of forms of political engagement and collective identification (such as indigeneity), resonating with Fried’s (1967) and Scott’s (1998) notions that the state implies some sort of process, one of ‘restructuring’ and ‘making legible’. Consequently, this thesis argues that from the Chiquitano perspective, the election of Bolivia’s first indigenous president in 2005 and his radical state reform project through the 2006-2007 Constituent Assembly, has not fundamentally transformed previous patterns of indigenous-state engagement. It posits that the more successful resistance continues to reside, perhaps more subtly, in comunidades ’ socio-cultural relations. -

Arqueologías Vitales

ARQUEOLOGÍAS VITALES Henry Tantaleán y Cristóbal Gnecco (Editores) Los contenidos de este libro están protegidos por la Ley. Está prohibido reproducir cualquiera de los contenidos de este libro para uso comercial sin el consentimiento expreso de los depositarios de los derechos. En todo caso, se permite el uso de los materiales para uso educacional. Para otras cuestiones, pueden contactar con el editor en: www.jasarqueologia.es Primera edición: enero de 2019 © Edición: JAS Arqueología S.L.U. Plaza de Mondariz 6, 28029 Madrid www.jasarqueologia.es Edición: Jaime Almansa Sánchez Diseño de cubierta: Emilio Simmonds © Textos: Los autores © Imágenes: Especificado en el pie. ISBN: 978-84-16725-22-9 Depósito Legal: M-3084-2019 Impreso por: Service Point www.servicepoint.es Impreso y hecho en España - Printed and made in Spain CONTENIDO Conversación en Lima 1 Cristóbal Gnecco y Henry Tantaleán Seguir la huella y curar el rastro. Memorias de una 19 experiencia colectiva de investigación y militancia en el campo de arqueología argentina Ivana Carina Jofré Arqueo-devenires, Zarankin-centrismos y presentes 61 contaminados Texto: Andrés Zarankin Dibujos: Iván Zigarán Cuando descubres que el arqueólogo local no eres tú. 71 Dos encuentros con la isla Pariti Juan Villanueva Criales Sueño y catarsis: hacia una arqueología post- 91 humanista José Roberto Pellini La cerámica de Anuma’i y las marcas del fin del 123 mundo Fabíola Andréa Silva La arqueología en la era del multiculturalismo 151 neoliberal: una reflexión autobiográfica desde San Pedro de Atacama (norte de Chile) Patricia Ayala Rocabado Confesiones de un postarqueólogo 173 Cristóbal Gnecco Entre el Cauca y el Magdalena: una historia apócrifa 193 de la arqueología colombiana en el último tercio del siglo XX Wilhelm Londoño Cuando el “otro” eres tú.