Photography in Bakumatsu Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry and Nancy Rosin Collection of Early Photography of Japan

Henry and Nancy Rosin Collection of Early Photography of Japan Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives Washington, D.C. 20013 [email protected] https://www.freersackler.si.edu/research/archives/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Local Numbers................................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series FSA A1999.35 A1: Photo album from the studio of Adolpho Farsari, [1860 - ca. 1900]................................................................................................................... 3 Series FSA A1999.35 A2: Photo album from the studio of Tamamura, [1860 - ca. 1900]...................................................................................................................... -

Download PDF Version

100 Books With Original Photographs 1846–1919 PAUL M. HERTZMANN, INC. MARGOLIS & MOSS 100 BOOKS With ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS 1846–1919 PAUL M. HERTZMANN, INC. MARGOLIS & MOSS Paul M. Hertzmann & Susan Herzig David Margolis & Jean Moss Post Office Box 40447 Post Office Box 2042 San Francisco, California 94140 Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504-2042 Tel: (415) 626-2677 Fax: (415) 552-4160 Tel: (505) 982-1028 Fax: (505) 982-3256 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Association of International Photography Art Dealers Antiquarian Booksellers’Association of America Private Art Dealers Association International League of Antiquarian Booksellers 90. TERMS The books are offered subject to prior sale. Customers will be billed for shipping and insurance at cost. Payment is by check, wire transfer, or bank draft. Institutions will be billed to suit their needs. Overseas orders will be sent by air service, insured. Payment from abroad may be made with a check drawn on a U. S. bank, international money order, or direct deposit to our bank account. Items may be returned within 5 days of receipt, provided prior notification has been given. Material must be returned to us in the same manner as it was sent and received by us in the same condition. Inquiries may be addressed to either Paul Hertzmann, Inc. or Margolis & Moss Front cover and title page illustrations: Book no. 82. 2 introduction his catalog, a collaborative effort by Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc., and Margolis & Moss, T reflects our shared passion for the printed word and the photographic -

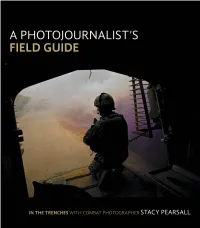

A Photojournalist's Field Guide: in the Trenches with Combat Photographer

A PHOTOJOURNALISt’S FIELD GUIDE IN THE TRENCHES WITH COMBAT PHOTOGRAPHER STACY PEARSALL A Photojournalist’s Field Guide: In the trenches with combat photographer Stacy Pearsall Stacy Pearsall Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education. Copyright © 2013 by Stacy Pearsall Project Editor: Valerie Witte Production Editor: Katerina Malone Copyeditor: Liz Welch Proofreader: Erin Heath Composition: WolfsonDesign Indexer: Valerie Haynes Perry Cover Photo: Stacy Pearsall Cover and Interior Design: Mimi Heft Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

Photography: a Survey of New Reference Sources

RSR: Reference Services Review. 1987, v.15, p. 47 -54. ISSN: 0090-7324 Weblink to journal. ©1987 Pierian Press Current Surveys Sara K. Weissman, Column Editor Photography: A Survey of New Reference Sources Eleanor S. Block What a difference a few years make! In the fall 1982 issue of Reference Services Review I described forty reference monographs and serial publications on photography. That article concluded with these words, "a careful reader will be aware that not one single encyclopedia or solely biographical source was included... this reviewer could find none in print... A biographical source proved equally elusive" (p.28). Thankfully this statement is no longer valid. Photography reference is greatly advanced and benefited by a number of fine biographical works and a good encyclopedia published in the past two or three years. Most of the materials chosen for this update, as well as those cited in the initial survey article, emphasize the aesthetic nature of photography rather than its scientific or technological facets. A great number of the forty titles in the original article are still in print; others have been updated. Most are as valuable now as they were then for good photography reference selection. However, only those sources published since 1982 or those that were not cited in the original survey have been included. This survey is divided into six sections: Biographies, Dictionaries (Encyclopedias), Bibliographies, Directories, Catalogs, and Indexes. BIOGRAPHIES Three of the reference works cited in this survey have filled such a lamented void in photography reference literature that they stand above the rest in their importance and value. -

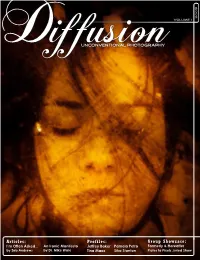

Download the Free Pdf of Volume I

9 volume 1 200 DiffusionUnconventional Photography Articles: Profiles: Group Showcase: I’m Often Asked... An Ironic Manifesto Jeffrey Baker Pamela Petro Formerly & Hereafter by Zeb Andrews by Dr. Mike Ware Tina Maas Sika Stanton Plates to Pixels Juried Show Praise for Diffusion, Volume I “Avant-garde, breakthrough and innovative are just three adjectives that describe editor Blue Mitchell’s first foray into the world of fine art photography magazines. Diffusion magazine, tagged as unconventional photography delivers on just that. Volume 1 features the work of Jeffrey Baker, Pamela Petro, Tina Maas and Sika Stanton. With each artist giving you a glimpse into how photography forms an integral part of each of their creative journey. The first issue’s content is rounded out by Zeb Andrews’ and Dr. Mike Ware. Zeb Andrews’ peak through his pin-hole world is complimented by an array of his creations along with the 900 second exposure “Fun Center” as the show piece. And Dr. Mike unscrambles the history of iron-based photographic processes and the importance of the printmaker in the development of a fine art image. At a time when we are seeing a mass migration to on-line publishing and on-line magazine hosting, the editorial team at Diffusion proves you can still deliver an outstanding hard-copy fine art photography magazine. I consumed my copy immediately with delight; now when is the next issue coming out?” - Michael Van der Tol “Regardless of the retrospective approach to the medium of photography, which could be perceived by many as a conservative drive towards nostalgia and sentimentality. -

Japan on Display: Photography and the Emperor P

Japan on Display Sixty years on from the end of the Pacifi c War, Japan on Display examines representations of the Meiji Emperor, Mutsuhito (1852–1912), and his grandson the Shôwa Emperor, Hirohito, who was regarded as a symbol of the nation, in both war and peacetime. Much of this representation was aided by the phenomenon of photography. The introduction and development of photography in the nineteenth century coincided with the need to make Hirohito’s grandfather, the young Meiji Emperor, more visible. It was important to show the world that Japan was a civilised nation, worthy of international respect. Photobooks and albums became a popular format for presenting seemingly objective images of the monarch, reminding the Japanese of their proximity to the emperor, and the imperial family. In the twentieth century, these ‘national albums’ provided a visual record of wars fought in the name of the emperor, while also documenting the reconstruction of Tokyo, scientifi c expeditions, and imperial tours. Collectively, they create a visual narrative of the nation, one in which Emperor Hirohito (1901–89) and science and technology were prominent. Drawing on archival documents, photographs, and sources in both Japanese and English, this book throws new light on the history of twentieth-century Japan and the central role of Hirohito. With Japan’s defeat in the Pacifi c War, the emperor was transformed from wartime leader to peace-loving scientist. Japan on Display seeks to understand this reinvention of a more ‘human’ emperor and the role that photography played in the process. Morris Low is Professor of East Asian Sciences and Technology at Johns Hop- kins University. -

The Development and Growth of British Photographic Manufacturing and Retailing 1839-1914

The development and growth of British photographic manufacturing and retailing 1839-1914 Michael Pritchard Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Imaging and Communication Design Faculty of Art and Design De Montfort University Leicester, UK March 2010 Abstract This study presents a new perspective on British photography through an examination of the manufacturing and retailing of photographic equipment and sensitised materials between 1839 and 1914. This is contextualised around the demand for photography from studio photographers, amateurs and the snapshotter. It notes that an understanding of the photographic image cannot be achieved without this as it directly affected how, why and by whom photographs were made. Individual chapters examine how the manufacturing and retailing of photographic goods was initiated by philosophical instrument makers, opticians and chemists from 1839 to the early 1850s; the growth of specialised photographic manufacturers and retailers; and the dramatic expansion in their number in response to the demands of a mass market for photography from the late1870s. The research discusses the role of technological change within photography and the size of the market. It identifies the late 1880s to early 1900s as the key period when new methods of marketing and retailing photographic goods were introduced to target growing numbers of snapshotters. Particular attention is paid to the role of Kodak in Britain from 1885 as a manufacturer and retailer. A substantial body of newly discovered data is presented in a chronological narrative. In the absence of any substantive prior work this thesis adopts an empirical approach firmly rooted in the photographic periodicals and primary sources of the period. -

BAKUMATSUYA ۥ¢Â€ PDF Catalogue

Catalogue for September 2020 1057-29 Ichigao-cho, Aoba-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa 225-0024, JAPAN Inspection by appointment only www.bakumatsuya.com - 2 - Catalogue of The Exhibition of Paintings of Hokusai the first exhibition of Hokusai works held in Japan The exhibition was 'Held at the Japan Fine Art Association, Uyeno Park, Tokio from 13th to 30th January, 1900.' This copy signed by the author, Bunshichi Kobayashi, the well known art dealer, and given to his friend and collector, Frederick W. Gookin. According to WorldCat, no copies in institutions outside Japan except on microfiche. One copy at Nichibunken in Kyoto. Excessively rare and important Hokusai reference. Quite possibly more than a few of the Hokusai paintings described and/or photographed in the book were lost in the 1923 earthquake or WWII. Comprehensive catalogue with 223 items described and most in some detail. Fifty plates showing important works. Fascinating 16-page preface by Ernest Fenellosa. Interestingly, for some reason the catalogue itself wasn't published until 18 months after the exhibition was held and it seems very few were ever printed. Colour, woodblock printed frontispiece of Hokusai. Hard cover with brown boards. Tokyo. Bunshichi Kobayashi. 1901. Colour frontispiece+16pp preface. 167[1]pp+50 b&w plates+colophon page. 26.9 x 18.5cm. In very good condition. Covers starting to separate and are a bit worn with minor loss at top of spine. Corners a little bumped. Internally very good with almost no wear. nb32070018 Price: $11,892 - 3 - Flags of the Different Daimios of Japan Wonderful scroll in Japanese and English Fascinating scroll showing the names of the 29 daimyo (lord) of Japan, their provinces, their flag, the leading family's name, along with the wealth of each daimyo as measured in rice (one koku was roughly the amount of rice needed to feed one person for one year). -

Photography in Lancaster

The Art o/ Photography in Lancaster By M. LATHER HEISEY HEN Robert Burns said: "0 wod some Pow'r the giftie gie W us, to see oursels as ithers see us !" he did not realize that one answer to his observation would be given to the world by the invention of photography. Until that time men saw their images "as through a glass darkly," by the medium of skillfully painted portraits by the old masters, by reflections in mirrors, placid streams or highly polished surfaces. Years before 1839, artists and chemists had been experiment- ing with methods to retain a permanent image or reflection of an object upon a canvass or other surface. In August of that year photography "came to light" when Louis J. M. Daguerre (1789- 1851) first publicly announced his process in Paris. "Daguerre, a French painter of dioramas, astonished the scientific world by pro- ducing sun pictures obtained by exposing the surface of a highly polished silver tablet to the vapor of iodine in a dark room, and then placing the tablet in a camera obscuro, and exposing it to the sunlight. A latent image of the object within the range of the camera was thus obtained, and this image was developed by expos- ing the tablet to the fumes of mercury, heated to a temperature of about 170° Fahrenheit. The image thus secured was 'fixed' or made permanent by dipping the tablet into a solution of hyposul- phite of soda, and then carefully washing and drying the plate." 1 The development of photography to the perfection of the pres- ent time was, like all inventions, a slow and steady advance. -

Museum Collections Totaled 142.1 Million

National Collections Program Staff William G. Tompkins, National Collections Coordinator Lauri A. Swann, Assistant National Collections Coordinator Cover Photo: Smithsonian Institution Building towers from the Arts and Industries Building showing both roofs. This image first appeared in the 1931 United States National Museum Report. For additional information or copies of this report contact: National Collections Program, Arts & Industries Building, Room 3101, 900 Jefferson Drive, SW, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 - 0404 tel. (202) 357-3125 fax (202) 633-9214 e-mail [email protected]. 2000 Collection Statistics National Collections Program Smithsonian Institution Archives Director’s Statement I am pleased to present to the Board of Regents, the Secretary, and Smithsonian staff the annual statistical report on the collections of the Smithsonian. This report contains a wealth of information on Institutional trends in the acquisition, loan, and management of the National Collections. First published in 1987, the statistics have become an important indicator of both progress and problems in collections management, informing resource allocators and the Institution’s personnel of events occurring in a given year, and trends reflected over time. This year’s Collection Statistics marks a departure from previous years. More important, it marks the beginning of changes that will occur as the National Collections Program (NCP) of Smithsonian Institution Archives reviews the needs and wishes of its multiple audiences. In the coming year, NCP will seek to identify new and expanded methods to communicate findings on the growth, care, and use of the National Collections. This year’s change moves the publication toward increased uniformity and comparability of data. -

Mirrors and Windows American Photography Since 1960

List of Photographers Mirrors Robert Adams Elliott Erwitt Leslie Krims Sylvia Plachy and Windows Diane Arbus Reed Estabrook William Larson Eliot Porter Larry Fink Helen Levitt Douglas Prince American Bill Arnold Lewis Baltz Lee Friedländer Sol LeWitt Edward Ranney Photography Anthony Barboza William Gedney Jerome Liebling Robert Rauschenberg Joseph Bellanca Ralph Gibson Danny Lyon Leland Rice since 1960 Jim Bengston Frank Gohlke Joan Lyons Edward Ruscha Richard Benson Emmet Gowin Nathan Lyons Lucas Samaras Gary Beydler Jan Groover Michael McLoughlin Naomi Savage The Museum Paul Caponigro Ernst Haas Jerry McMillan Stephen Shore of Modem Art, Walter Chappell Charles Hagen Larry McPherson Art Sinsabaugh Michael Ciavolino Betty Hahn Robert Mapplethorpe Keith A. Smith New York William Clift Gary L. Hallman Roger Mertin Rosalind Solomon July 28-October 2, 1978 Mark Cohen Charles Harbutt Ray K. Metzker Eve Sonneman Linda Connor Chauncey Hare Sheila Metzner Wayne Sorce Marie Cosindas Dave Heath Joel Meyerowitz Lew Thomas Robert Cumming Robert Heinecken Duane Michals George A. Tice Darryl Curran Richard P. Hume Richard Misrach Jerry N. Uelsmann William Current Scott Hyde John Mott-Smith Max Waldman Joseph Dankowski Christopher P. James Nicholas Nixon Todd Walker Judy Dater Ken Josephson Tetsu Okuhara Andy Warhol This exhibition has been made Bruce Davidson Simpson Kalisher Arthur Oilman Henry Wessel, Jr. possible by generous support from Roy DeCarava Colleen Kenyon Bill Owens Geoff Winningham Philip Morris Incorporated and Tod Papageorge Far left: Jerry N. Uelsmann. Untitled. 1964. The Museum of Modem Art, New York. Purchase the National Endowment for the Arts John M. Divola, Jr. Irwin B. Klein Garry Winogrand in Washington, D.C. -

Metropolitan Useum Of

Miss Caliill THE ETROPOLITAN NEWS USEUM OF ART FOR M RELEASE Friday, May 8, 1959 FIFTH AYE.at82 STREET • NEW YORK TR 9-5500 Press View: Thursday, May 7, 2-4:30 p.m. PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE FINE ARTS, EXHIBIT AT METROPOLITAN MUSEUM Works of 55 contemporary photographers will be exhibited beginning Friday, May 8, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art as works of art. A new national project, "Photography in the Fine Arts," will present 85 photo graphs (30 color and 55 black & white) chosen by a jury of distinguished exponents of the fine arts, v/ith James J. Rorimer, Director of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, as chairman. The photographs v/ere selected from 438 nominations submitted by authoritative sources in the field of photography. The exhibit will be on view in a special Photographic Gallery at the Metro politan Museum through Labor Day, and it has been proposed that the photographs in it should become a part of the Museum's permanent collections. The project was developed by Ivan Dmitri, noted photographer, under the spon sorship of the national weekly magazine SATURDAY REVIEW. It has been in the course of preparation for nine months. Its origin was a column in SATURDAY REVIEW which described Mr. Dmitri's conviction that more museums should collect and display great photographs as art. Response from 21 museum directors indicated wide interest and revealed the need for finding an unbiased method for screening the best work in the field of photography, as is done with contemporary painting. The breadth of the jury for the present exhibition and the final 85 photographic selections are the result.