Emmet Gowin's Photographs of Edith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Project #3: Inspired By… - Description Critique Date - 3/29/19 (Fri)

Project #3: Inspired by… - Description Critique Date - 3/29/19 (Fri) "The world is filled to suffocating. Man has placed his token on every stone. Every word, every image, is leased and mortgaged. We know that a picture is but a space in which a variety of images, none of them original, blend and clash." – Sherrie Levine Conceptual Requirements: In this project, you will do your best to interpret the style of a particular photographer who interests you. You will research them as well as their work in order to make photographs that have a signature aesthetic or approach that is specific to them, and also contribute your ideas. Technical Requirements: 1. Start with the list on the back of this page (the Project Description sheet), and start web searches for these photographers. All the ones listed are masters in their own right and a good starting point for you to begin your search. Select one and confirm your choice with me by the due date (see the syllabus). 2. After choosing a photographer, go on the web and to the library to check out books on them, read interviews, and look at every image you can that is made by them. Learn as much as you can and take notes on your sources. 3. Type your name, date, and “Project 3: Inspired by...” at the top of a Letter sized page. Then write a 2 page research paper on your chosen photographer. Be sure to include information such as where and when they were born, where it is that they did their work, what kind of camera and film formats they used, their own personal history, etc. -

Henry Holmes Smith Papers

HENRY HOLMES SMITH PAPERS Compiled by Charles Lamb and Mary Ellen McGoldrick GUIDE SERIES NUMBER EIGHT CENTER FOR CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHY UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA Center for Creative Photography University of Arizona Copyright© 1983 Arizona Board of Regents This guide was produced with the assistance of the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. Contents The Critic's Tale: A Commentary on Henry Holmes 5 PrefureSmith's Writings on Photography, by Susan E. Cohen 7 Introduction to the Henry Holmes Smith Papers 17 Correspondence, 1929- 80 18 Writings by Henry Holmes Smith, 1925- 82 20 Nonfiction 20 Fiction 22 Miscellaneous 23 Education, 1930s- 70s 24 Courses Taught by Smith 24 New Bauhaus School and Institute of Design 24 Courses Taken by Smith 24 Lectures, Conferences, and Workshops 24 Administrative Records (Indiana University) 25 Exhibitions, 1929- 83 26 One-Man Exhibitions of Smith's Work 26 Group Exhibitions that Included Smith's Work 26 Miscellaneous Exhibitions (Not Including Smith's Work) 28 Photographic Organizations 29 Photographer's Exhibition Service, 1959- 63 29 Professional Associations, 1947 - 81 29 Other Material 30 Personal and Financial Records, 1950s- 70s 30 Reference Files, 1940s- 70s 30 Audio Visual Material, 1950s- 80 30 Related Resources 31 Prints 31 Videotape Library 31 Henry Holmes Smith: A Biographical Essay, by Howard Bossen 32 Henry Holmes Smith Bibliography, by Howard Bossen 37 Published Works by Henry Holmes Smith 37 Writings About Henry Holmes Smith 39 Preface The Guide Series is designed to inform scholars and students of the history of photography about the larger photograph, manuscript, and negative collections at the Center for Creative Photography. -

EDWARD BURTYNSKY 80 Spadina Avenue, Suite 207 Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5V 2J4

CURRICULUM VITAE • Complete EDWARD BURTYNSKY 80 Spadina Avenue, Suite 207 Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5V 2J4 www.EdwardBurtynsky.com Born St. Catharines, Ontario, 1955 Education 1982 - Bachelor of Applied Arts - Photographic Arts (Media Studies Program), Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario 1974 - 1976 - Graphic Arts, Niagara College, Welland, Ontario 1985 to present - Photographic artist, entrepreneur, educator, lecturer. Established Toronto Image Works, a darkroom rental facility, custom lab, digital imaging centre and new media computer training centre. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2013 Burtynsky: Water, New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA) / Contemporary Art Center (CAC), New Orleans, USA, October 5, 2013 - January 19, 2014 Burtynsky: Water, Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, USA, October 24 - December 14 (reception November 6) Burtynsky: Water, Flowers, Cork Street, London, UK, October 16 - November 23 (reception October 15) Burtynsky: Water, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, USA, October 5 - October 26 (reception October 5) Burtynsky: Water, Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York, NY, USA, September 19 - November 2 (reception September 19) Burtynsky: Water, Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, NY, USA, September 18 - November 2 (reception September 18) Burtynsky: Water, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto, Canada, September 5 - October 12 (reception September 12) Edward Burtynsky: The Landscape that we Change, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinberg, Ontario, Canada, June 29 - September 29 Nature Transformed: Edward Burtynsky’s Vermont -

Notable Photographers Updated 3/12/19

Arthur Fields Photography I Notable Photographers updated 3/12/19 Walker Evans Alec Soth Pieter Hugo Paul Graham Jason Lazarus John Divola Romuald Hazoume Julia Margaret Cameron Bas Jan Ader Diane Arbus Manuel Alvarez Bravo Miroslav Tichy Richard Prince Ansel Adams John Gossage Roger Ballen Lee Friedlander Naoya Hatakeyama Alejandra Laviada Roy deCarava William Greiner Torbjorn Rodland Sally Mann Bertrand Fleuret Roe Etheridge Mitch Epstein Tim Barber David Meisel JH Engstrom Kevin Bewersdorf Cindy Sherman Eikoh Hosoe Les Krims August Sander Richard Billingham Jan Banning Eve Arnold Zoe Strauss Berenice Abbot Eugene Atget James Welling Henri Cartier-Bresson Wolfgang Tillmans Bill Sullivan Weegee Carrie Mae Weems Geoff Winningham Man Ray Daido Moriyama Andre Kertesz Robert Mapplethorpe Dawoud Bey Dorothea Lange uergen Teller Jason Fulford Lorna Simpson Jorg Sasse Hee Jin Kang Doug Dubois Frank Stewart Anna Krachey Collier Schorr Jill Freedman William Christenberry David La Spina Eli Reed Robert Frank Yto Barrada Thomas Roma Thomas Struth Karl Blossfeldt Michael Schmelling Lee Miller Roger Fenton Brent Phelps Ralph Gibson Garry Winnogrand Jerry Uelsmann Luigi Ghirri Todd Hido Robert Doisneau Martin Parr Stephen Shore Jacques Henri Lartigue Simon Norfolk Lewis Baltz Edward Steichen Steven Meisel Candida Hofer Alexander Rodchenko Viviane Sassen Danny Lyon William Klein Dash Snow Stephen Gill Nathan Lyons Afred Stieglitz Brassaï Awol Erizku Robert Adams Taryn Simon Boris Mikhailov Lewis Baltz Susan Meiselas Harry Callahan Katy Grannan Demetrius -

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

John Sexton Photography Workshops

JOHN SEXTON PHOTOGRAPHY WORKSHOps 2007–2008 WORKSHOP SCHEDULE JOHN SEXTON PHOTOGRAPHY WORKSHOps 2007–2008 INTRODUCTION hotography is an illusion. It is amazing that human beings consider a photograph to be a STAFF representation of reality. As photographers, I think we are privileged to work in the medium that has such powerful illusionistic characteristics. I clearly remember the first photographic DIRECTOR P John Sexton exhibition I attended more than thirty years ago. Seeing those photographs changed not only my photography, but changed my life. The three photographers in the exhibition were Ansel Adams, ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Laura Bayless Edward Weston, and Wynn Bullock. I had never seen works of art that were so inspiring. I still find beauty, power, and challenges in the black and white silver printing process, and continue to PHOTOGRAPHIC ASSISTANTS enjoy working within that magical medium. As the technology of photographic imaging evolves, it Anne Larsen Jack Waltman is exciting to see how the voice of photographers expressing themselves — whether with pixels or silver grains — still resonates in their prints. INSTRUCTOR John Sexton The workshops included in this year’s program will provide opportunities to learn from successful working photographers. The instructors and assistants will willingly share their experiences with CORPORATE SPONSORS you — both successes and mistakes — they have NO SECRETS. The workshops are an intense expe- Eastman Kodak Company rience, in which one will be immersed in photography from early in the morning until late at night. Bogen Imaging You will be tired at the end of the workshop, but will be filled with information and inspiration. -

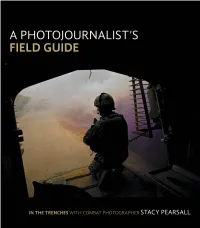

A Photojournalist's Field Guide: in the Trenches with Combat Photographer

A PHOTOJOURNALISt’S FIELD GUIDE IN THE TRENCHES WITH COMBAT PHOTOGRAPHER STACY PEARSALL A Photojournalist’s Field Guide: In the trenches with combat photographer Stacy Pearsall Stacy Pearsall Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education. Copyright © 2013 by Stacy Pearsall Project Editor: Valerie Witte Production Editor: Katerina Malone Copyeditor: Liz Welch Proofreader: Erin Heath Composition: WolfsonDesign Indexer: Valerie Haynes Perry Cover Photo: Stacy Pearsall Cover and Interior Design: Mimi Heft Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations appear as requested by the owner of the trademark. -

Photography: a Survey of New Reference Sources

RSR: Reference Services Review. 1987, v.15, p. 47 -54. ISSN: 0090-7324 Weblink to journal. ©1987 Pierian Press Current Surveys Sara K. Weissman, Column Editor Photography: A Survey of New Reference Sources Eleanor S. Block What a difference a few years make! In the fall 1982 issue of Reference Services Review I described forty reference monographs and serial publications on photography. That article concluded with these words, "a careful reader will be aware that not one single encyclopedia or solely biographical source was included... this reviewer could find none in print... A biographical source proved equally elusive" (p.28). Thankfully this statement is no longer valid. Photography reference is greatly advanced and benefited by a number of fine biographical works and a good encyclopedia published in the past two or three years. Most of the materials chosen for this update, as well as those cited in the initial survey article, emphasize the aesthetic nature of photography rather than its scientific or technological facets. A great number of the forty titles in the original article are still in print; others have been updated. Most are as valuable now as they were then for good photography reference selection. However, only those sources published since 1982 or those that were not cited in the original survey have been included. This survey is divided into six sections: Biographies, Dictionaries (Encyclopedias), Bibliographies, Directories, Catalogs, and Indexes. BIOGRAPHIES Three of the reference works cited in this survey have filled such a lamented void in photography reference literature that they stand above the rest in their importance and value. -

The Museum of Modern Art Momaexh 1221 Masterchecklist

£'Y-h. 1221 The Museum of Modern Art 11 West 53 Street, New York, N. Y.10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart RORS AND WINDOWS: AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY SINCE 1960 exhibition circulated by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and made possible by erous support from Phillip Morris Incorporated and the National Endowment for the Arts. 1 Q;KLIST: 184 framed photographs 3 photographic works mounted in vitrines 1 book MoMAExh_1221_MasterChecklist 1 Wall label (SP) Indicates Security plates on back of works Museum Frame Box Number Artist/Title/Date/Process/Credit HXW No. 313.78 ROBERT ADAMS (born 1937) Burned and Clearcut, East of Arch Ca.,e, 16 x 20" 1 Oregon. 1976. The Museum of Modern Att. Acquired with matching funds from Samuel Wm. Sax and the National Endowment for the Arts. L 314.78 Burned and Clearcut, East of Arch Cape, 16 x 20" 3 Oregon. 1976. The Museum of Modern Art. Acquired with matching funds from Samuel Wm. Sax and the National Endowment for the Arts. 3. 315.78 North of Briggsdale, Colorado. 1973. 14 x 17" (SP) 3 The Museum of Modern Art. Acquired with matching funds from Samuel Wm. Sax and the National Endowment for the Arts. 4. 316.78 North of Briggsdale, Colorado. 1973. 14 x 17" (SP) 1 The Museum of Modern Art. Acquired with matching funds from Samuel Wm. Sax and the National Endowment for the Arts. 5. 321.72 DIfu~E ARBUS (1923-1971) A Child Crying, New Jersey. 1967. 27 x 22" 7 The Museum of Modern Art. Mrs. Douglas Auchincloss Fund. -

Words Without Pictures

WORDS WITHOUT PICTURES NOVEMBER 2007– FEBRUARY 2009 Los Angeles County Museum of Art CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Charlotte Cotton, Alex Klein 1 NOVEMBER 2007 / ESSAY Qualifying Photography as Art, or, Is Photography All It Can Be? Christopher Bedford 4 NOVEMBER 2007 / DISCUSSION FORUM Charlotte Cotton, Arthur Ou, Phillip Prodger, Alex Klein, Nicholas Grider, Ken Abbott, Colin Westerbeck 12 NOVEMBER 2007 / PANEL DISCUSSION Is Photography Really Art? Arthur Ou, Michael Queenland, Mark Wyse 27 JANUARY 2008 / ESSAY Online Photographic Thinking Jason Evans 40 JANUARY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Amir Zaki, Nicholas Grider, David Campany, David Weiner, Lester Pleasant, Penelope Umbrico 48 FEBRUARY 2008 / ESSAY foRm Kevin Moore 62 FEBRUARY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Carter Mull, Charlotte Cotton, Alex Klein 73 MARCH 2008 / ESSAY Too Drunk to Fuck (On the Anxiety of Photography) Mark Wyse 84 MARCH 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Bennett Simpson, Charlie White, Ken Abbott 95 MARCH 2008 / PANEL DISCUSSION Too Early Too Late Miranda Lichtenstein, Carter Mull, Amir Zaki 103 APRIL 2008 / ESSAY Remembering and Forgetting Conceptual Art Alex Klein 120 APRIL 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Shannon Ebner, Phil Chang 131 APRIL 2008 / PANEL DISCUSSION Remembering and Forgetting Conceptual Art Sarah Charlesworth, John Divola, Shannon Ebner 138 MAY 2008 / ESSAY Who Cares About Books? Darius Himes 156 MAY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Jason Fulford, Siri Kaur, Chris Balaschak 168 CONTENTS JUNE 2008 / ESSAY Minor Threat Charlie White 178 JUNE 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM William E. Jones, Catherine -

Rubens Was Artist, Scholar, Diplomat--And a Lover of Life

RUBENS WAS ARTIST, SCHOLAR, DIPLOMAT--AND A LOVER OF LIFE An exhibit at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts shows that this Flemish genius truly lived in the right place at the right time by Henry Adams Smithsonian, October, 1993 Of all the great European Old Masters, Rubens has always been the most difficult and puzzling for Americans. Thomas Eakins, the famed American portraitist, once wrote that Rubens' paintings should be burned. Somewhat less viciously, Ernest Hemingway made fun of his fleshy nudes—which have given rise to the adjective "Rubenesque"—in a passage of his novel A Farewell to Arms. Here, two lovers attempt to cross from Italy into Switzerland in the guise of connoisseurs of art. While preparing for their assumed role, they engage in the following exchange: "'Do you know anything about art?' "'Rubens,' said Catherine. "'Large and fat,' I said." Part of the difficulty, it is clear, lies in the American temperament. Historically, we have preferred restraint to exuberance, been uncomfortable with nudes, and admired women who are skinny and twiglike rather than abundant and mature. Moreover, we Americans like art to express private, intensely personal messages, albeit sometimes strange ones, whereas Rubens orchestrated grand public statements, supervised a large workshop and absorbed the efforts of teams of helpers into his own expression. In short, Rubens can appear too excessive, too boisterous and too commercial. In addition, real barriers of culture and At the age of 53, a newly married Rubens celebrated by painting the joyous, nine-foot- background block appreciation. Rubens wide Garden of Love.