Fairy Tale Femininities: a Discourse Analysis of Snow White Films 1916-2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

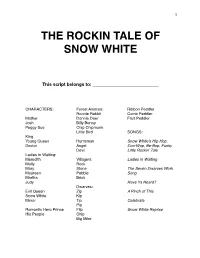

Rockin Snow White Script

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine. -

Characters' Actions and Reactions

Dear Family Member, Welcome to our next unit of study, “Characters’ Actions and Reactions.” We are beginning our second unit of study in the Benchmark Advance program. As a reminder, each three-week unit features one topic. As with the previous unit, I am providing suggested activities you and your child can do together at home to build on the work we’re doing in class. In our second unit of study, “Characters’ Actions and Reactions,” your child will explore how characters drive the action of a plot. For example, in the fairy tale “Snow White Meets the Huntsman,” students discover the lengths that the queen is willing to go to destroy Snow White, all due to her envy and vanity. Your child will also explore some of the morals and messages in Aesop’s Fables, where are character-driven stories meant to teach children centuries ago how to behave and lead their own lives. his will help students begin thinking about how they come across as characters in their own lives, with actions and reactions similar to those of characters they read about. he selections include a variety of genres, including fables, fairy tales, fantasy, animal fantasy, and informational texts. I’m looking forward to this exciting unit, exploring with your children the wide range of characters we encounter in literature. It will be fun to discover how the children connect with the various characters as well as recognize the historical signifcance of some of our favorite children’s tales. As always, should you have any questions about our reading program or about your child’s progress, please don’t hesitate to contact me. -

Snow White in the Spanish Cultural Tradition

Bravo, Irene Raya, and María del Mar Rubio-Hernández. "Snow White in the Spanish cultural tradition: Analysis of the contemporary audiovisual adaptations of the tale." Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: New Perspectives on Production, Reception, Legacy. Ed. Chris Pallant and Christopher Holliday. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 249–262. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501351198.ch-014>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 23:19 UTC. Copyright © Chris Pallant and Christopher Holliday 2021. You may share this work for non- commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 249 14 Snow White in the Spanish cultural tradition: Analysis of the contemporary audiovisual adaptations of the tale Irene Raya Bravo and Mar í a del Mar Rubio-Hern á ndez Introduction – Snow White, an eternal and frontier-free tale As one of the most popular fairy tales, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has international transcendence. Not only has it been translated into numerous languages around the world, but it has also appeared in several formats since the nineteenth century. However, since 2000, an increase in both fi lm and television adaptations of fairy tales has served to retell this classic tales from a variety of different perspectives. In the numerous Snow White adaptations, formal and thematic modifi cations are often introduced, taking the story created by Disney in 1937 as an infl uential reference but altering its narrative in diverse ways. In the case of Spain, there are two contemporary versions of Snow White that participate in this trend: a fi lm adaptation called Blancanieves (Pablo Berger, 2012) and a television adaptation, included as an episode of the fantasy series Cu é ntame un cuento (Marcos Osorio Vidal, 99781501351228_pi-316.indd781501351228_pi-316.indd 224949 116-Nov-206-Nov-20 220:17:500:17:50 250 250 SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS 2014). -

Little Red Riding Hood

LLiittttllee RReedd RRiiddiinngg HHoooodd Brothers Grimm Once upon a time there was a dear little girl who was loved by everyone who looked at her, but most of all by her grandmother, and there was nothing that she would not have given to the child. Once she gave her a little riding hood of red velvet, which suited her so well that she would never wear anything else; so she was always called 'Little Red Riding Hood.' One day her mother said to her: 'Come, Little Red Riding Hood, here is a piece of cake and a bottle of wine; take them to your grandmother, she is ill and weak, and they will do her good. Set out before it gets hot, and when you are going, walk nicely and quietly and do not run off the path, or you may fall and break the bottle, and then your grandmother will get nothing; and when you go into her room, don't forget to say, "Good morning", and don't peep into every corner before you do it.' 'I will take great care,' said Little Red Riding Hood to her mother, and gave her hand on it. The grandmother lived out in the wood, half a league from the village, and just as Little Red Riding Hood entered the wood, a wolf met her. Red Riding Hood did not know what a wicked creature he was, and was not at all afraid of him. 'Good day, Little Red Riding Hood,' said he. 'Thank you kindly, wolf.' 'Where do you go so early, Little Red Riding Hood?' 'To my grandmother's.' 'What have you got in your apron?' 'Cake and wine; yesterday was baking-day, so poor sick grandmother is to have something good, to make her stronger.' 'Where does your grandmother live, Little Red Riding Hood?' 'A good quarter of a league farther on in the wood; her house stands under the three large oak-trees, the nut-trees are just below; you surely must know it,' replied Little Red Riding Hood. -

Feminism and Magic in Snow White

Dittmeier 1 Feminism and Magic in Snow White Magic is something that has always been very prevalent in fairy tales. Many fairy tales include young women—complacent, innocent, and invariably beautiful young women—who are either terrorized by an evil witch, helped out of a bad circumstance by a fairy godmother, or both. They are expected to handle their misfortune gracefully and show kindness even to their enemies, which they are often rewarded for, and generally this reward is marriage. However, some of these fairy tales can be seen through a more feminist lens. Magical fairy tale women do not have to just be either evil or the bumbling fairy godmother who helps the heroine get her marriage reward. Snow White, for example, has more control over her story than may be apparent. There is a hidden feminist ideology in Snow White that we can see through Snow White’s use of magic. Witches—women who can use magic—are, in modern times, a feminist symbol. The witch is a woman who has her own power, and in the case of some stories, Macbeth, for example, they have power to drive the plot (Guadagnino, 2018). The witch can be a positive symbol for a woman who has her own agency. If we look closely, we can see clues that indicate that Snow White is not only a witch, but that she is using her own power to drive her story along. Magic is evident from the very beginning of Snow White. Snow White’s mother is sewing by the open window, and she pricks her finger. -

Little Snow-White

Little Snow-White Germany, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm Once upon a time in mid winter, when the snowflakes were falling like feathers from heaven, a beautiful queen sat sewing at her window, which had a frame of black ebony wood. As she sewed, she looked up at the snow and pricked her finger with her needle. Three drops of blood fell into the snow. The red on the white looked so beautiful, that she thought, "If only I had a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as this frame." Soon afterward she had a little daughter that was as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as ebony wood, and therefore they called her Little Snow-White. Now the queen was the most beautiful woman in all the land, and very proud of her beauty. She had a mirror, which she stood in front of every morning, and asked: Mirror, mirror, on the wall, Who in this land is fairest of all? And the mirror always said: You, my queen, are fairest of all. And then she knew for certain that no one in the world was more beautiful than she. Now Snow-White grew up, and when she was seven years old, she was so beautiful, that she surpassed even the queen herself. Now when the queen asked her mirror: Mirror, mirror, on the wall, Who in this land is fairest of all? The mirror said: You, my queen, are fair; it is true. But Little Snow-White is still A thousand times fairer than you. -

SNOW WHITE Rehearsal Schedule Revised As of 2.13.18

SNOW WHITE Rehearsal Schedule Revised as of 2.13.18 January 13th – 27th 12:30-1:00 – Bunnies 1:00-1:30 – Birds 1:30-2:00 – Towns Children, Young Snow White, Young William 2:00-2:30 – Ravens, Evil Queen come only January 20th and 27th 2:30-3:30 – Snow White, Seven Dwarves 3:30-4:00 – Gypsies 4:00-4:30 – King’s Army, Dark Army, Captains of Dark Army, Evil Queen, King 4:30-5:30 – Fairies, Fairy Princess 5:30-6:30 – Snow White and Evil Queen February 3rd – 10th 12:30-1:30 – Bunnies, Birds, Snow White, Dwarves 1:30-2:30 – Snow White, Queen, King, Evil Queen, Dark Army, Captains of Dark Army, King’s Army, Young Snow White, Towns Children, Young William 2:30-3:00 – Snow White, Huntsman, Seven Dwarves, Older William, Captains of Dark Army, Dark Army, Evil Queen 3:00-3:30 – Huntsman, Snow White, Evil Queen, Older William, Captains of Dark Army 3:30-4:00 – Snow White, Huntsman, Gypsies, Large Creature 4:00-4:30 – Huntsman, Evil Queen, Older William, Dark Army, Gypsies, Captains of Dark Army, Snow White 4:30-5:00 – Snow White, Huntsman, Seven Dwarves, Older William, Fairy Princess, Fairies 5:00-5:30 – Snow White, Older William, Ravens, Evil Queen, Huntsman 5:30-6:30 – Seven Dwarves, Snow White, Huntsman, Older William, Snow White, Dark Army, Evil Queen, Captains of the Dark Army February 17th 12:30-1:30 – Bunnies, Birds, Snow White, Dwarves 1:30-2:30 – Snow White, Queen, King, Evil Queen, Dark Army, Captains of Dark Army, King’s Army, Young Snow White, Towns Children, Young William 2:30-3:30 – Snow White, Huntsman, Seven Dwarves, Older William, Captains -

Harga Sewaktu Wak Jadi Sebelum

HARGA SEWAKTU WAKTU BISA BERUBAH, HARGA TERBARU DAN STOCK JADI SEBELUM ORDER SILAHKAN HUBUNGI KONTAK UNTUK CEK HARGA YANG TERTERA SUDAH FULL ISI !!!! Berikut harga HDD per tgl 14 - 02 - 2016 : PROMO BERLAKU SELAMA PERSEDIAAN MASIH ADA!!! EXTERNAL NEW MODEL my passport ultra 1tb Rp 1,040,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 2tb Rp 1,560,000 NEW MODEL my passport ultra 3tb Rp 2,500,000 NEW wd element 500gb Rp 735,000 1tb Rp 990,000 2tb WD my book Premium Storage 2tb Rp 1,650,000 (external 3,5") 3tb Rp 2,070,000 pakai adaptor 4tb Rp 2,700,000 6tb Rp 4,200,000 WD ELEMENT DESKTOP (NEW MODEL) 2tb 3tb Rp 1,950,000 Seagate falcon desktop (pake adaptor) 2tb Rp 1,500,000 NEW MODEL!! 3tb Rp - 4tb Rp - Hitachi touro Desk PRO 4tb seagate falcon 500gb Rp 715,000 1tb Rp 980,000 2tb Rp 1,510,000 Seagate SLIM 500gb Rp 750,000 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb Rp 1,550,000 1tb seagate wireless up 2tb Hitachi touro 500gb Rp 740,000 1tb Rp 930,000 Hitachi touro S 7200rpm 500gb Rp 810,000 1tb Rp 1,050,000 Transcend 500gb Anti shock 25H3 1tb Rp 1,040,000 2tb Rp 1,725,000 ADATA HD 710 750gb antishock & Waterproof 1tb Rp 1,000,000 2tb INTERNAL WD Blue 500gb Rp 710,000 1tb Rp 840,000 green 2tb Rp 1,270,000 3tb Rp 1,715,000 4tb Rp 2,400,000 5tb Rp 2,960,000 6tb Rp 3,840,000 black 500gb Rp 1,025,000 1tb Rp 1,285,000 2tb Rp 2,055,000 3tb Rp 2,680,000 4tb Rp 3,460,000 SEAGATE Internal 500gb Rp 685,000 1tb Rp 835,000 2tb Rp 1,215,000 3tb Rp 1,655,000 4tb Rp 2,370,000 Hitachi internal 500gb 1tb Toshiba internal 500gb Rp 630,000 1tb 2tb Rp 1,155,000 3tb Rp 1,585,000 untuk yang ingin -

The Eight Elements for Identifying the Story of Snow White: from Grimms' to DEFA to Disney by Chloé Johnston a THESIS Submitt

The Eight Elements for Identifying the Story of Snow White: From Grimms’ to DEFA to Disney by Chloé Johnston A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Psychology (Honors Associate) Presented August 26, 2020 Commencement June 2021 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Chloé Johnston for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Psychology presented on August 26, 2020. Title: An Analysis of Snow White: From Grimms’ to DEFA to Disney. Abstract approved: Sebastian Heiduschke The Grimms’ Brothers left their mark on history when they published their first edition of the Kinder- und Hausmärchen gesammelt durch die Brüder Grimm (Nursery and Household tales Collected by the Brothers Grimm) in 1812. Among these newly published tales was that of Snow White. Within the paradigm of the United States, the most salient example of Grimms’ fairy tales are the better-known Disney films that have shaped the childhoods of many generations; starting in 1937, when Disney released its first feature-length animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. In 1962, an East German Production Company by the name of Deutsche Filmaktiengesellschaft (DEFA), produced their own adaptation of Snow White, Schneewittchen. The purpose of this thesis is to highlight that despite differences in time, culture, and medium the story of Snow White is still recognizable with the inclusion of eight core elements. These eight being: Snow White the character, the Evil Queen, the Mirror, the Huntsman, the Seven Dwarfs, the Apple, Snow White’s Revival, and her Happily Ever After. -

Fairy Tale Reader's Theater: Snow White

Fairy Tale Reader’s Theater: Snow White Reader Roles: Narrator, Queen, Snow White, Mirror, Huntsman, Dwarf 1, Dwarf 2, Dwarf 3, Prince Narrator: Once upon a time, there was a sweet and kind-hearted princess Narrator: But the mirror’s answer did not change, and the Queen was very named Snow White. Her mother died when she was born and her father soon angry. married another woman. Snow White’s new stepmother was very beautiful, Queen: Clearly, there is only one thing to be done. Snow White must be but also very wicked, and she hated her pretty stepdaughter, Snow White eliminated. Huntsman! because everyone else in the kingdom loved her so much. Huntsman: Yes, your Majesty. Queen: (talking to herself) Why does everyone like her? She is not as beautiful as me. I hate her! Queen: I order you to take Snow White deep into the forest and kill her! Bring me her heart so I know you have done what I asked. Narrator: The Queen believed that if she was the most beautiful person in the kingdom, then the people and the king would love her forever, more than Huntsman: Yes, your Majesty. they loved Snow White. She had a magic mirror, and every day, she asked it Narrator: The next day, the Huntsman took Snow White deep into the the same question. forest. When they were far from anyone who could help, he took out a knife. Queen: Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all? Snow White began to weep. Narrator: Every day, the mirror answered .. -

Character Analysis of Snow White in the Film Snow White and the Huntsman

CHARACTER ANALYSIS OF SNOW WHITE IN THE FILM SNOW WHITE AND THE HUNTSMAN A Thesis Submitted to Letters of Adab and Humanities Faculty In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Strata One (S1) By: DESI DWI WULANDARI 109026000129 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND HUMANITIES STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2014 ABSTRACT DESI DWI WULANDARI, Character analysis of Snow White in the film Snow White and the Huntsman Thesis: English Letters Department. Letters and Humanities Faculty. State Islamic University Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, 2013. This Research discusses character analysis of Snow White in the film Snow White and the Huntsman film by Rupert Sanders’s film. The method used is descriptive qualitative method by describing and analyzing the film. The writer also uses character theory and masculinity concept. The objectives of the research are to know Snow White character which is different from Walt Disney film. Snow White and the Huntsman is a film portraying the life of Snow White who experiences difficulties due to her stepmother, Revenna. In gaining back her rights, Snow White relies on her own strength, and abilities. By applying the concept of masculinity, Snow White is described differently than other Snow White characters. The result of research is that as brave, smart and firm. This representation exposes her masculinity and it is different than common description of Snow White which is describe more feminine. Her masculinity is also supported by some symbols of masculinity : -

A Grimm Evolution by Kylee Sullivan

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2016 Vol. 14 A Grimm Evolution Huntsman cuts open the Wolf’s stomach to save Little Red and her grandmother and throws it in the river Kylee Sullivan full of stones while the Wolf is still alive. This does not English 345 mean, however, that there have never been adaptations of various fairytales that aren’t darker than their Disney From the time we are young we are introduced counterparts. to fairytales; stories about princesses and princes, of One adaptation in particular that does fall on magic and talking animals, and cautionary tales saying the slightly darker scale is a book series that is aimed to always do the right thing and to know better than at older children. Michael Buckley’s series The Sisters to trust a stranger. Many children are introduced to Grimm tells the story of 11-year-old Sabrina Grimm the concept of fairytales from bedtime stories or from and her 8-year-old sister Daphne. The books begin with the film adaptations made by Disney. However, if you letting us know that Sabrina and Daphne’s parents went look closer at fairytales, namely those collected by the missing and the only clue to their disappearance was Brothers Grimm, you will see just how dark they truly a blood red handprint left on their car window. After are. How could it be possible that the stories we grew escaping from every horrible foster home they were sent up with as children have such a dark background when to (descriptions are made of the young girls being cuffed we ourselves are so used to them being about all things to radiators and kept in dog cages in some instances) the good and happily ever after? And, if they were so dark to girls are put in the custody of an elderly woman named begin with, why have these stories been adapted again Relda Grimm and her companion Mr.