Tenenbaum-Mastersreport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bringing Regional Rail Service to the Historic Cotton Belt Corridor DART Current and Future Rail Services

SILVER LINE REGIONAL RAIL GROUNDBREAKING COMMEMORATIVE EDITION Bringing Regional Rail Service to the Historic Cotton Belt Corridor DART Current and Future Rail Services NW PLANO PARK & RIDE PLANO PARKER ROAD To Denton JACK HATCHELL DOWNTOWN PLANO TRANSIT CTR. Preside SHILOH nt G 12TH STREET ROAD e sh Turnpike (future) o r g e Bu Dallas North Tollway CITYLINE/BUSH NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD UT DALLAS GALATYN PARK TRINITY MILLS CARROLLTON ADDISON KNOLL TRAIL RICHARDSON ARAPAHO CENTER Map Legend DOWNTOWN CARROLLTON ADDISON CYPRESS WATERS TRANSIT CTR. DFW (DALLAS) SPRING VALLEY MapTo FortLegendBlue Worth Line AIRPORT FARMERS NORTH BRANCH Red Line DOWNTOWN Blue Line FARMERS BRANCH GARLAND GARLAND LBJ/CENTRAL Map LegendGreenDFW Line DFW DOWNTOWN Red Line ROWLETT AIRPORT AIRPORT FOREST LANE FOREST/JUPITER OrangeBlueTerminal Line B Line Terminal A Green Line HIDDEN ROYAL LANE LBJ/SKILLMAN Orange Line BELT LINE ROWLETT Red Line RIDGE Map Legend LAKE HIGHLANDS Weekdays Peak Only (future) WALNUT OrangeDFW Line IRVING CONVENTION WALNUT HILL/DENTON HILL TrinityGreen RailwayLine Express CENTER Blue Line (No Sunday Service) PARK LANE Lake Ray Orange Line NORTH LAKE LAS COLINAS S. GARLAND Hubbard Orange Line COLLEGE Red Line TRANSIT CTR. TEXRailWeekdays (Trinity Peak Metro) Only URBAN CENTER UNIVERSITY WHITE ROCK LOVERS A-Train (DCTA) Green Line BACHMAN OrangeTrinity Line Railway Express UNIVERSITY OF DALLAS PARK LANE Weekdays Peak Only (No Sunday Service) LOVE FIELD White Rock M-Line Trolley VIA BUS 524 HIGHLAND LAKE RAY Orange Line Lake TrinityTEXRail Railway (Trinity Express Metro)Inset Map LOOP 12 BURBANK PARK HUBBARD Dallas(No Sunday Streetcar Service) (future) INWOOD/LOVE FIELD SMU/MOCKINGBIRD TRANSIT CTR. -

Richardson Cover

AN ADVISORY SERVICES PANEL REPORT Richardson, Texas Urban Land $ Institute Richardson, Texas A Plan for Transit-Oriented Development June 11–16, 2000 An Advisory Services Panel Report ULI–the Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, N.W. Suite 500 West Washington, D.C. 20007-5201 About ULI–the Urban Land Institute LI–the Urban Land Institute is a non- sented include developers, builders, property profit research and education organiza- owners, investors, architects, public officials, tion that promotes responsible leadership planners, real estate brokers, appraisers, attor- U in the use of land in order to enhance neys, engineers, financiers, academicians, stu- the total environment. dents, and librarians. ULI relies heavily on the experience of its members. It is through member The Institute maintains a membership represent- involvement and information resources that ULI ing a broad spectrum of interests and sponsors a has been able to set standards of excellence in wide variety of educational programs and forums development practice. The Institute has long been to encourage an open exchange of ideas and shar- recognized as one of America’s most respected ing of experience. ULI initiates research that and widely quoted sources of objective informa- anticipates emerging land use trends and issues tion on urban planning, growth, and development. and proposes creative solutions based on that research; provides advisory services; and pub- This Advisory Services panel report is intended lishes a wide variety of materials to disseminate to further the objectives of the Institute and to information on land use and development. make authoritative information generally avail- able to those seeking knowledge in the field of Established in 1936, the Institute today has some urban land use. -

Doug Allen-Dallas

The DART Perspective Doug Allen Executive Vice President Program Development Dallas Area Rapid Transit Why DART? • Growing Mobility Problems • “World Class” Image • Vision 9 Fixed Guideway 9 Multi-modal 9 Regional Mobility History • DART was created to implement a vision 9 Fixed Guideway 9 Multi-modal • We had some problems along the way 9 Local economy 9 Public input 9 Political support 9 Credibility 9 Failure of Bond Referendum History • 1983 – DART established • 1988 – Bond referendum failure • 1989 – New Directions System Plan campaign • 1992 – Rail construction begins • 1996 – Opening of LRT Starter System • 2000 – Long term debt package passed • 2001-02 – Opening of extensions • 2006 – $700 Million FFGA The Mission To build and operate a safe, efficient and effective transportation system that, within the DART Service Area, provides mobility, improves the quality of life, and stimulates economic development. FY 2006 Ridership by Mode 36.1 Million 18.6 Million 18% 36% 44% 2% 2.4 Million 44.3 Million System Overview THE DART SYSTEM BUS • Provides area-wide coverage 9 700 square miles 9 Over 100 routes • Flexible 9 Local 9 Express 9 Crosstown 9 Feeders 9 Paratransit 9 Innovative services • Carries 44.3 million riders/year (FY ’06) System Overview THE DART SYSTEM Light Rail • Provides high capacity, quality transit within busiest corridors 9 20 mile Starter System 9 Additional 25 miles in 2002-3 9 Another 48 miles in planning & design • Benefits include 9 Service Reliability 9 Consistent time savings 9 Attracts new users 9 Stimulates -

Tramway Renaissance

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com OCTOBER 2018 NO. 970 FLORENCE CONTINUES ITS TRAMWAY RENAISSANCE InnoTrans 2018: Looking into light rail’s future Brussels, Suzhou and Aarhus openings Gmunden line linked to Traunseebahn Funding agreed for Vancouver projects LRT automation Bydgoszcz 10> £4.60 How much can and Growth in Poland’s should we aim for? tram-building capital 9 771460 832067 London, 3 October 2018 Join the world’s light and urban rail sectors in recognising excellence and innovation BOOK YOUR PLACE TODAY! HEADLINE SUPPORTER ColTram www.lightrailawards.com CONTENTS 364 The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association OCTOBER 2018 Vol. 81 No. 970 www.tautonline.com EDITORIAL EDITOR – Simon Johnston [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOr – Tony Streeter [email protected] WORLDWIDE EDITOR – Michael Taplin 374 [email protected] NewS EDITOr – John Symons [email protected] SenIOR CONTRIBUTOR – Neil Pulling WORLDWIDE CONTRIBUTORS Tony Bailey, Richard Felski, Ed Havens, Andrew Moglestue, Paul Nicholson, Herbert Pence, Mike Russell, Nikolai Semyonov, Alain Senut, Vic Simons, Witold Urbanowicz, Bill Vigrass, Francis Wagner, Thomas Wagner, 379 Philip Webb, Rick Wilson PRODUCTION – Lanna Blyth NEWS 364 SYSTEMS FACTFILE: bydgosZCZ 384 Tel: +44 (0)1733 367604 [email protected] New tramlines in Brussels and Suzhou; Neil Pulling explores the recent expansion Gmunden joins the StadtRegioTram; Portland in what is now Poland’s main rolling stock DESIGN – Debbie Nolan and Washington prepare new rolling stock manufacturing centre. ADVertiSING plans; Federal and provincial funding COMMERCIAL ManageR – Geoff Butler Tel: +44 (0)1733 367610 agreed for two new Vancouver LRT projects. -

AGENCY PROFILE and FACTS RTD Services at a Glance

AGENCY PROFILE AND FACTS RTD Services at a Glance Buses & Rail SeniorRide SportsRides Buses and trains connect SeniorRide buses provide Take RTD to a local the metro area and offer an essential service to our sporting event, Eldora an easy RTDway to Denver services senior citizen at community. a glanceMountain Resort, or the International Airport. BolderBoulder. Buses and trains connect and the metro trainsarea and offer an easy way to Denver International Airport. Access-a-Ride Free MallRide Access-a-RideAccess-a-Ride helps meet the Freetravel MallRideneeds of passengers buses with disabilities.Park-n-Rides Access-a-RideFlexRide helps connect the entire length Make connections with meet theFlexRide travel needsbuses travel of within selectof downtown’s RTD service areas.16th Catch FlexRideour to connect buses toand other trains RTD at bus or passengerstrain with servies disabilities. or get direct accessStreet to shopping Mall. malls, schools, and more.89 Park-n-Rides. SeniorRide SeniorRide buses serve our senior community. Free MallRide FlexRideFree MallRide buses stop everyFree block onMetroRide downtown’s 16th Street Mall.Bike-n-Ride FlexRideFree buses MetroRide travel within Free MetroRide buses Bring your bike with you select RTDFree service MetroRide areas. buses offer convenientoffer convenient connections rush-hour for downtown commuterson the bus along and 18th train. and 19th Connectstreets. to other RTD connections for downtown SportsRides buses or trains or get direct commuters along 18th and Take RTD to a local sporting event, Eldora Mountain Resort, or the BolderBoulder. access toPark-n-Rides shopping malls, 19th streets. schools, Makeand more.connections with our buses and trains at more than 89 Park-n-Rides. -

Trinity Mills Station Market Overview

Report Trinity Mills Station Market Overview Prepared for: City of Carrollton, Texas and Dallas Area Rapid Transit Prepared by: Economic & Planning Systems, Inc. April 24, 2013 EPS #20842 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ................................................................. 1 Trinity Mills Station Properties .................................................................................... 1 Surrounding Land Use ............................................................................................... 3 Transportation and Access ......................................................................................... 4 Planning and Land Use Policy Context .......................................................................... 4 2. REGIONAL MARKET FRAMEWORK ................................................................................ 7 Employment Trends .................................................................................................. 7 Population Growth .................................................................................................. 12 Subject Property Demographics ................................................................................ 15 Conclusions – Regional Growth Trends ...................................................................... 17 3. TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT ON THE DART SYSTEM ............................................... 18 Red and Blue Lines, Northeast Dallas ....................................................................... -

DART.Org--Red Line Weekends/Los Fines De Semana to Parker

Red Line Weekends/Los fines de semana To Parker Road Station Effective: March 30, 2019 -- denotes no service to this stop this trip Weekend rail service suspended Downtown Dallas only, effective March 30-September 2019. DART Rail in downtown Dallas will be discontinued each weekend beginning March 30, for roughly six months, to allow track replacement along Pacific Avenue and Bryan Street. DART will replace worn light rail tracks, add and repair crossovers, and repair streets and drainage along the rail corridor. Track improvements will be made between Pearl/Arts District Station and West End Station. Union Station will not be affected. Interrupted Rail Segments: Red and Blue lines - between Union Station and Pearl/Arts District Station; Green Line - between Victory Station and Deep Ellum Station; Orange Line - between Victory Station and LBJ/Central Station, and between Victory Station and Parker Road Station. Five separate bus shuttle routes will be in operation: Two routes stop at every Central Business District station. Three express routes connect Pearl/Arts District Station, Union Station and Victory Station. An additional Express route (936) will connect Mockingbird Station and Bachman Station. Click here to learn more. WESTMORELAND HAMPTON TYLER DALLAS 8TH & CEDARS CONVENTION UNION PEARL/ARTS CITYPLACE/UPTOWN MOCKINGBIRD LOVERS PARK WALNUT FOREST LBJ / SPRING ARAPAHO GALATYN CITYLINE/BUSH DOWNTOWN PARKER STATION STATION VERNON ZOO CORINTH STATION CENTER STATION DISTRICT STATION STATION LANE LANE HILL LANE CENTRAL VALLEY CENTER -

Dfw International Airport

HOW TO RIDE Arrive on time to DFW Skip the traffic and stress INTERNATIONAL Save money AIRPORT Bags ride free on board DART Accessible for riders with disabilities Trains arrive at DFW regularly from 3:50 a.m. to 1:19 a.m. daily Trip planning and easy payment with GoPassSM. For questions or concerns, call DART Customer Information at 214.979.1111 161-109-614 • DART to DFW How To Ride.indd 1 7/24/14 5:16 PM 161-109-614 • DART to DFW Opening How To Ride/Outside • 8.5” tall x 3.5” wide folded/7” flat • Built @ Proofed @ 100% HOURS OF OPERATION AT THE AIRPORT Arrivals Checking Bags 3:50 a.m. – 1:19 a.m., 7 days a week American Airlines passengers (flying from any Departures terminal) can walk from the rail station to Terminal A, 4:18 a.m. – 1:12 a.m., weekdays; check in, check bags and pass through a security 4:06 a.m. – 12:12 a.m., weekends checkpoint; passengers taking American Airlines flights from another terminal can do the same and then take Skylink to their departure terminal. Passengers using other airlines with bags to check ORANGE LINE CONNECTIONS should keep them and use the Terminal Link bus shuttle to reach the desired terminal; those with Belt Line Station carry-on luggage can go through security and 8 minutes take Skylink. Bachman Station Using Terminal Link – Terminal Link is free and (transfer point for Green Line) stops near the rail station. 31 minutes SW Medical District/Parkland Station Using Skylink – Skylink is located inside the 41 minutes terminal, beyond airport security. -

Highland Park Carrollton Farmers Branch Addison

LAKE LEWISVILLE 346 348 EXCHANGE PKWY 348 LEGACY DR PARKWOOD SH 121 SHOPS AT 452 348 452 LEGACY 346346 LEGACY DR TENNYSON 347 P 183 451 208 NORTH PLANO NORTHWEST PLANO DART ON-CALL ZONE PARK AND RIDE 183, 208, 346, 347, PRESTON RD 348, 451, 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 829 LAKESIDE US-75 N. CENTRAL EXPWY. COLLIN COUNTY MARKET COMMUNITY 350 COLLEGE JUPITER RD 350 TEXAS HEALTH 451 PLANO RD PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL PLANO PARKER RD 452 R RD COMMUNICATIONS 347 PARKER RD PARKER ROAD STATION PARKE 350, 410, 452 183 PRESTON RD. DART ON-CALL, TI Shuttle, Texoma Express 410 CUSTER RD SHOPS AT RD COIT PARK BLVD INDEPENDENCE PARK BLVD CREEK WILLOWBEND 410 ALMA ARBOR 531 347 PARK BLVD PARK BLVD CHEYENNE 870 451 BAYLOR MEDICAL CTR. 18TH 870 AT CARROLLTON HEBRON PLANO DOWNTOWN PLANO STATION MEDICAL CENTER 870 FLEX 208 OF PLANO 15TH 15TH OHIO 14TH IN T PARKWOOD E 350 R 13TH 870 N A PLANO PKWY TI 210 COLLIN CREEK MALL ON JACK HATCHELL TRANSIT CENTER FM 544 AL P KWY 841 210, 350, 451, 452, 841 FLEX SH-121 347 210 BAYLOR REGIONAL 870 843 AVE K AVE 843 841 MEDICAL CTR. ROSEMEADE PKWY 534 841 PLANO PKWY PLANO PKWY HEBRON to Denton (operated by DCTA) 531 347 841 MARSH LUNA 350 841 410 WAL-MART 883 Fri/Sun 841 ROUND GROVE NPIKE NORTH STAR RD TIMBERGREEN H TUR NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD STATION P S BUSH TURNPIKE STATION 333 U 883 UTD Shuttle, 841-843 FLEX PEAR RIDGE PEAR B IH-35E STEMMONS FRWY. -

REFERENCE BOOK March 2019

DALLAS AREA RAPID TRANSIT REFERENCE BOOK March 2019 Version 10.0 WHAT The Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) Reference Book is a convenient and easy to use compilation of information on the DART system. It provides staff with key data, maps and contacts. The objective is to allow staff to respond to inquiries, with consistent, accurate information in a timely manner. WHO The DART Reference Book was compiled by the Capital Planning Division of the Growth/Regional Development Department. Numerous DART departments provide input and assist Capital Planning with annual updates. WHEN DART Capital Planning coordinates an update after each fiscal year ending September 30. Because some financial information does not become immediately available, the Reference Book update is completed by the second quarter (March) of the following fiscal year. AVAILABILITY A limited number of printed copies are made for senior management. A PDF version of the Reference Book is available for DART staff on DART InfoStation, and also on www.DART.org under About DART. VERSION CONTROL VERSION NUMBER VERSION DATE DESCRIPTION OF CHANGES 1 8.2010 DRAFT 2 3.2011 FY10 Actual/FY11 Budget Update 3 4.2012 FY11 Actual/FY12 Budget Update 4 4.2013 FY12 Actual/FY13 Budget Update 5 3.2014 FY13 Actual/FY14 Budget Update New Board Member committee 5.1 5.2014 assignments/minor edits 6 3.2015 FY14 Actual/FY15 Budget Update Corrected LRT on-time performance for 6.1 7.2015 PDF version only. 7 3.2016 FY15 Actual/FY16 Budget Update 8 3.2017 FY16 Actual/FY17 Budget Update 9 3.2018 FY17 Actual/FY18 Budget Update 10 3.2019 FY18 Actual/FY19 Budget Update II DART REFERENCE BOOK – MARCH 2019 DART POINTS-OF-CONTACT ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES DART MAILING/PHYSICAL ADDRESS 214-749-3278 DALLAS AREA RAPID TRANSIT P.O. -

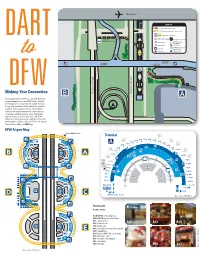

Making Your Connection

DART Rail System Map DOWNTOWN ROWLETT DFW AIRPORT STATION Open 2014 Irving Convention Center Belt Line Making Your Connection During peak times (4:30-7 a.m. and 2:15-5:30 p.m. weekday departures from DFW Airport Station), the Orange Line travels from the station through Irving, into downtown Dallas and to the northern terminus of the system at Parker Road Station in Plano. Off-peak, it follows the same path but terminates at LBJ/Central Station. Select late- night Orange Line trains will travel from DFW Exploring Airport Station to downtown; from there they will Popular Destinations go through Deep Ellum and end at Fair Park Station. Check out schedules at DART.org. DART DFW Airport Map Convention Center District. One of the largest in the nation, the Kay Bailey Hutchison (Dallas) Convention Center hosts major national and international conventions, meetings, antique and Exit to DART Station Terminal auto shows, and other events. The Omni Dallas Hotel is connected to it via sky bridge. Convention Center Station Fair Park. The largest collection of Art Deco exhibit buildings in the U.S., Fair Park is a historical treasure that plays host to the State Fair of Texas®. Other attractions include the Heart of Dallas Bowl football game and year-round museums. Fair Park Station Dallas Arts District. The Dallas Arts District is the largest arts district in the nation, spanning 68 acres and comprising Entry numerous venues of cultural as well as architectural from distinction. Pearl/Arts District Station DART Omni Dallas Hotel Station NorthPark Center. Shoppers from all over the world are drawn to NorthPark’s one-of-a-kind collection of luxury and fashion-forward retailers. -

History of Mass Transit

A NEW WAY TO CONNECT TO TRAVEL Ryan Quast Figure 1.1 A NEW WAY TO CONNECT TO TRAVEL A Design Thesis Submitted to the Department of Architecture and Landscape Architecture of North Dakota State University By Ryan Quast In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Architecture Primary Thesis Advisor Thesis Committee Chair May 2015 Fargo, North Dakota List of Tables and Figures Table of Contents Figure 1.1 Train entering COR station 1 Cover Page................................................................................................1 Taken by author Signature Page....................................................................................... ...3 Figure 1.2 Northstar commuter train 13 Table of Contents......................................................................................4 www.northstartrain.org Tables and Figures....................................................................................5 Thesis Proposal.....................................................................................10 Figure 2.1 Render of The COR 15 Thesis Abstract............................................................................11 coratramsey.com/node/23 Narrative of the Theoretical Aspect of the Thesis..................12 Figure 2.2 Development plan for COR 15 Project Typology.........................................................................13 coratramsey.com/sites/default/files/COR-Development-Plan-6.0.pdf Typological Research (Case Studies)...................................................14