BAKS 16 Full Issue.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Find PDF # South Korean Television Drama

LCFONI58EGNH # Book # South Korean television drama South Korean television drama Filesize: 7.08 MB Reviews I actually started reading this article ebook. I actually have read and i also am certain that i will likely to go through once again again in the future. You are going to like just how the article writer compose this ebook. (Mariane Kerluke) DISCLAIMER | DMCA N37PIG9QSLDB ^ Book ~ South Korean television drama SOUTH KOREAN TELEVISION DRAMA Reference Series Books LLC Dez 2011, 2011. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 245x187x7 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 139. Chapters: Salut D'Amour, Spring Waltz, Dae Jo Yeong, Boys Over Flowers, Korean drama, Yi San, What's Up Fox, Princess Hours, Mom's Dead Upset, Likeable or Not, Papa, Hur Jun, The Phoenix, My Lovely Sam Soon, List of La Dolce Vita episodes, Delightful Girl Choon-Hyang, King of Baking, Kim Takgu, Emperor of the Sea, I'm Sorry, I Love You, Love Truly, Endless Love soundtracks, Prosecutor Princess, We are Dating Now, Time Between Dog and Wolf, A Good Day For The Wind To Blow, A Love to Kill, Daughters-in-Law, City of Glass, Brilliant Legacy, The King of Legend, Wife Returns, Super Junior Mini-Drama, Gourmet, Autumn in My Heart, The World That They Live In, Winter Sonata, Mystery 6, Family's Honor, The Last Scandal of My Life, Dal-Ja's Spring, DramaFever, Beethoven Virus, Golden Bride, Summer Scent, Wonderful Life, Queen Seondeok, Rooop Room Cat, Which Star Are You From, Sang Doo! Let's Go to School, The Snow Queen, Magic -

Siti Umayatun, S.Hum. TESIS

PERAN KOREA MUSLIM FEDERATION (KMF) DALAM PERTUMBUHAN ISLAM DI KOREA SELATAN TAHUN 1967-2015 M Disusun Oleh : Siti Umayatun, S.Hum. NIM : 1520510121 TESIS Diajukan Kepada Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Guna Memperoleh Gelar Master of Arts (M. A) Program Studi Interdisciplinary Islamic Studies (IIS) Konsentrasi Sejarah KebudayaanIslam YOGYAKARTA 2017 ABSTRAK Pada era Modern, bersamaan dengan Perang Korea tahun 1950-1953 M benih ajaran agama Islam mulai tumbuh di semenanjung Korea Selatan melalui kontak hubungan dengan pasukan perdamaian Turki. Dakwah bil hal tentara Turki selama terjadi perang melahirkan beberapa Muallaf generasi pertama Muslim Korea. Jumlah mereka pertahunnya meningkat sehingga terbentuk perkumpulan Muslim Korea dan tahun 1967 M menjadi organisasi Korea Muslim Federation (KMF) yang statusnya diakui oleh pemerintah Korea bahkan diberi surat izin mendirikan bangunan. Semua Muslim yang diorganisir KMF awalnya benar-benar bagian integral dari bangsa Korea yang menjadi Muallaf bukan karena kedatangan imigran Muslim dari negara-negara Islam. Sejak tahun 1970-an pemerintah Korea membantu KMF dalam perkembangan Islam, padahal selama itu mereka simpati pada Zionis dan pro Israel bahkan sejak masa kemerdekaan sampai sekarang berada di bawah naungan Amerika. Pemerintah Korea memperlakukan Muslim atas dasar sama dengan kelompok agama lainnya, tidak mendiskriminasi bahkan membuka pintu lebar-lebar dakwah KMF dengan memberikan sebidang tanah untuk pembangunan masjid dan universitas Islam. Meski Islam agama baru dan minoritas di Korea namun memiliki posisi terhormat dan stategis. Dalam memobilisasi perkembangan Islam, KMF melakukan kaderisasi mengirim beberapa pemuda Muslim Korea ke negara- negara Muslim untuk belajar Islam dan melakukan riset. Terlihat bahwa minoritas Muslim Korea punya nasip lebih cerah dan menjanjikan jika dibandingkan dengan keadaan minoritas Muslim lainnya. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Regionalismus und Stereotypen: Die Perzeption regionaler Dialekte in Südkorea“ verfasst von / submitted by Nikolaus Johannes Nagl BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2017/ Vienna 2017 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 871 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Koreanologie degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rainer Dormels Regionalismus und Stereotypen VORWORT Mein besonderer Dank für die tatkräftige Unterstützung beim Verfassen dieser Arbeit gebührt Herrn Prof. Rainer Dormels für die gewährte Freiheit beim Verfassen sowie die unzähligen konstruktiven Einwände und die Flexibilität bei der Verleihung von Fachliteratur. Des weiteren bedanke ich mich bei den Lektorinnen Jisun Kim und Susan Jo für hilfreiche Anregungen und bei Yuyoung Lee für die Hilfe bei der Erstellung des koreanischen Fragebogens. Großer Dank gebührt auch meinen Eltern sowie meinem Schulfreund Moritz für die motivieren Worte und nicht zuletzt auch den hunderten bereitwilligen vor Ort in Korea, die ihre Zeit zur Verfügung gestellt haben, um den Fragebogen zu beantworten. Schließlich möchte ich noch darauf hinweisen, dass mein stellenweiser Verzicht auf Gendern keineswegs auf eine diskriminierende Absicht zurückzuführen ist, sondern lediglich einem angenehmeren Lesefluss -

Communicative Language Teaching in Korean Public Schools: an Informal Assessment

The English Connection March 2001 Volume 5 / Issue 2 A bimonthly publication of Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages March 2001, Vol. 5, No. 2 Communicative Language Teaching in Korean Public Schools: An Informal Assessment by Dr. Samuel McGrath Introduction his article focuses on the current status of communicative language teaching in the public schools in T Korea. In order to promote communicative competence in the public schools, in 1992, the Ministry of Education mandated that English teachers use a communicative approach in class. They envisioned communi- cative language teaching (CLT) replacing the traditional audio-lingual method in middle school English teaching and the dominant grammar-translation method of high school teaching. The new approach was supposed to start in the schools in 1995. Six years have passed since the policy was adopted. However, no formal assessment by the government seems to have been done on the success or otherwise of the program. continued on page 6 Empowering Students with Learning Strategies . 9 Douglas Margolis Reading for Fluency . 11 Joshua A. Snyder SIG FAQs . 14 Calls for Papers!!! (numerous) Also in this issue KOTESOL To promote scholarship, disseminate information, and facilitate cross- cultural under standing among persons concerned with the teaching and learning of English in Korea www.kotesol.org1 The English Connection March 2001 Volume 5 / Issue 2 Language Institute of Japan Scholarship Again Available! The 2001 LIOJ Summer Workshop will be held August 5 to 10 in Odawara, Japan. The Language Institute of Japan Summer Workshops are perhaps Asia’s most recognized Language Teacher Training program. -

HCI2007 International 12Th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

Final Program HCI2007 International 12th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction jointly with: Symposium on Human Interface (Japan) 2007 7th International Conference on Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics 4th International Conference on Universal Access in Ηuman-Computer Interaction 2nd International Conference on Virtual Reality 2nd International Conference on Usability and Internationalization 2nd International Conference on Online 22-27 July 2007 Communities and Social Computing Beijing International 3rd International Conference on Augmented Cognition Convention Center 1st International Conference on Digital Human Modeling Beijing,HCI P.R. International China 2007 l Table of Contents Conference at a Glance Contacts 2 Conference at a Glance 3 Welcome Note 4 Opening Plenary Session 5 International Program Boards 6 Conference Exhibition 8 Tutorials Synopsis 10 Tutorials 1 - 19 11-28 General Chair BCI Workshops 29 Constantine Stephanidis University of Crete and FORTH-ICS, Greece Parallel Sessions Overview 30 Email: [email protected] • Wednesday 25 July 2007 30 Scientific Advisor • Thursday 26 July 2007 32 Gavriel Salvendy Purdue University, USA • Friday 27 July 2007 34 and Tsinghua University, P.R. China Parallel Sessions 36 Conference Administration Email: [email protected] • Wednesday 25 July 2007 Program Administration 08:00 - 10:00 36 Email: [email protected] 10:30 - 12:30 42 Registration Administration 13:30 - 15:30 48 Email: [email protected] 16:00 - 18:00 54 Student Volunteer Administration Email: [email protected] • Thursday 26 July 2007 Communications Chair and Editor of 08:00 - 10:00 60 HCI International News 10:30 - 12:30 66 Abbas Moallem Email: [email protected] 13:30 - 15:30 72 16:00 - 18:00 78 Organizational Board, P.R. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details MIGRATION AND INTEGRATION IN BORDERLESS VILLAGE: SOCIAL CAPITAL AMONG INDONESIAN MIGRANT WORKERS IN SOUTH KOREA KWANGWOO PARK Thesis submitted for qualification of PhD in Migration Studies UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX JULY 2014 ii University of Sussex Kwangwoo Park, PhD in Migration Studies Migration and Integration in Borderless Village: Social capital Among Indonesian Migrant Workers in South Korea SUMMARY Existing research (Guarnizo et al. 2003; Portes, 2001; Cohen and Sirkeci, 2005) has endeavoured to clarify the relationship between migrants’ transnational activities and their integration into the host society. Although there are both positive and negative perspectives on this relationship, it remains unclear whether migrants’ transnational activities are likely to help or hinder their integration into the host society (Vertovec, 2009). This thesis uses the lens of social capital and diaspora identity to shed light on the relationship between Indonesian migrants’ transnational activities and their integration in a multi-ethnic town in South Korea. The influx of migrants from various countries has led to the creation of what is called ‘Borderless Village’, where people have opportunities to build intercultural connections beyond their national group. -

STATEMENT UPR Pre-Session 33 on the Democratic People's Republic

STATEMENT UPR Pre-Session 33 on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) Geneva, April 5, 2019 Delivered by: The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK) 1- Presentation of the Organization HRNK is the leading U.S.-based bipartisan, non-governmental organization (NGO) in the field of DPRK human rights research and advocacy. Our mission is to focus international attention on human rights abuses in the DPRK and advocate for an improvement in the lives of 25 million DPRK citizens. Since its establishment in 2001, HRNK has played an intellectual leadership role in DPRK human rights issues by publishing over thirty-five major reports. HRNK was granted UN consultative status on April 17, 2018 by the 54-member UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). On October 4, 2018, HRNK submitted our findings to the UPR of the DPRK. Based on our research, the following trends have defined the human rights situation in the DPRK over the past seven years: an intensive crackdown on attempted escape from the country leading to a higher number of prisoners in detention; a closure of prison camps near the border with China while camps inland were expanded; satellite imagery analysis revealing secure perimeters inside these detention facilities with watch towers seemingly located to provide overlapping fields of fire to prevent escapes; a disproportionate repression of women (800 out of 1000 women at Camp No. 12 were forcibly repatriated); and an aggressive purge of senior officials. 2- National consultation for the drafting of the national report Although HRNK would welcome consultation and in-country access to assess the human rights situation, the DPRK government displays a consistently antagonistic attitude towards our organization. -

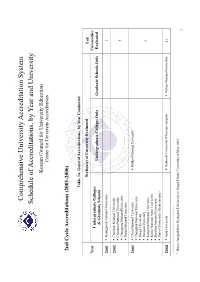

Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University

Comprehensive University Accreditation System Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University Korean Council for University Education Center for University Accreditation 2nd Cycle Accreditations (2001-2006) Table 1a: General Accreditations, by Year Conducted Section(s) of University Evaluated # of Year Universities Undergraduate Colleges Undergraduate Colleges Only Graduate Schools Only Evaluated & Graduate Schools 2001 Kyungpook National University 1 2002 Chonbuk National University Chonnam National University 4 Chungnam National University Pusan National University 2003 Cheju National University Mokpo National University Chungbuk National University Daegu University Daejeon University 9 Kangwon National University Korea National Sport University Sunchon National University Yonsei University (Seoul campus) 2004 Ajou University Dankook University (Cheonan campus) Mokpo National University 41 1 Name changed from Kyungsan University to Daegu Haany University in May 2003. 1 Andong National University Hanyang University (Ansan campus) Catholic University of Daegu Yonsei University (Wonju campus) Catholic University of Korea Changwon National University Chosun University Daegu Haany University1 Dankook University (Seoul campus) Dong-A University Dong-eui University Dongseo University Ewha Womans University Gyeongsang National University Hallym University Hanshin University Hansung University Hanyang University Hoseo University Inha University Inje University Jeonju University Konkuk University Korea -

Atrocity Crimes Against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar

BEARING WITNESS REPORT NOVEMBER 2017 “THEY TRIED TO KILL US ALL” Atrocity Crimes against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar SIMON-SKJODT CENTER FOR THE PREVENTION OF GENOCIDE United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Washington, DC www.ushmm.org The United States Holocaust Museum’s work on genocide and related crimes against humanity is conducted by the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide. The Simon-Skjodt Center is dedicated to stimulating timely global action to prevent genocide and to catalyze an international response when it occurs. Our goal is to make the prevention of genocide a core foreign policy priority for leaders around the world through a multipronged program of research, education, and public outreach. We work to equip decision makers, starting with officials in the United States but also extending to other governments and institutions, with the knowledge, tools, and institutional support required to prevent— or, if necessary, halt—genocide and related crimes against humanity. FORTIFY RIGHTS Southeast Asia www.fortifyrights.org Fortify Rights works to ensure and defend human rights for all. We investigate human rights violations, engage policy makers and others, and strengthen initiatives led by human rights defenders, affected communities, and civil society. We believe in the influence of evidence- based research, the power of strategic truth-telling, and the importance of working closely with individuals, communities, and movements pushing for change. We are an independent, nonprofit organization based in Southeast Asia and registered in the United States and Switzerland. The United State Holocaust Memorial Museum uses the name “Burma” and Fortify Rights uses the name “Myanmar” to describe the same country. -

The Human Costs and Gendered Impact of Sanctions on North Korea

THE HUMAN COSTS AND GENDERED IMPACT OF SANCTIONS ON NORTH KOREA OCTOBER 2019 The Human Costs and Gendered Impact of Sanctions on North Korea October 2019 Korea Peace Now, a global movement of women mobilizing to end the Korean War, has commissioned the present report to assess the human cost of sanctions on North Korea, and particularly on North Korean women. The broader aim of the Korea Peace Now campaign is to open space for dialogue on building peace in the Koreas, to move away from the constraints of geopolitics and to view the situation from a human centric perspective. The report was compiled and produced by an international and multidisciplinary panel of independent experts, including Henri Féron, Ph.D., Senior Fellow at the Center for International Policy; Ewa Eriksson Fortier, former Head of Country Delegation in the DPRK for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (retired); Kevin Gray, Ph.D., Professor of International Relations at the University of Sussex; Suzy Kim, Ph.D., Professor of Korean History at Rutgers University; Marie O’Reilly, Gender, Peace & Security Consultant; Kee B. Park, MD, MPH, Director of the DPRK Program at the Korean American Medical Association and Lecturer at Harvard Medical School; and Joy Yoon, Co-founder of Ignis Community and PYSRC Director of Educational Therapy. The report is a consensus text agreed among the authors and does not necessarily represent each individual author’s comprehensive position. Authors’ affiliations are for identifying purposes only and do not represent the views of those institutions unless specified. On the cover: A woman works at the Kim Jong Suk Pyongyang textile factory in Pyongyang, North Korea, on July 31, 2014. -

CELL PHONES in NORTH KOREA Has North Korea Entered the Telecommunications Revolution?

CELL PHONES IN NORTH KOREA Has North Korea Entered the Telecommunications Revolution? Yonho Kim ABOUT THE AUTHOR Yonho Kim is a Staff Reporter for Voice of America’s Korea Service where he covers the North Korean economy, North Korea’s illicit activities, and economic sanctions against North Korea. He has been with VOA since 2008, covering a number of important developments in both US-DPRK and US-ROK relations. He has received a “Superior Accomplishment Award,” from the East Asia Pacific Division Director of the VOA. Prior to joining VOA, Mr. Kim was a broadcaster for Radio Free Asia’s Korea Service, focused on developments in and around North Korea and US-ROK alliance issues. He has also served as a columnist for The Pressian, reporting on developments on the Korean peninsula. From 2001-03, Mr. Kim was the Assistant Director of The Atlantic Council’s Program on Korea in Transition, where he conducted in-depth research on South Korean domestic politics and oversaw program outreach to US government and media interested in foreign policy. Mr. Kim has worked for Intellibridge Corporation as a freelance consultant and for the Hyundai Oil Refinery Co. Ltd. as a Foreign Exchange Dealer. From 1995-98, he was a researcher at the Hyundai Economic Research Institute in Seoul, focused on the international economy and foreign investment strategies. Mr. Kim holds a B.A. and M.A. in International Relations from Seoul National University and an M.A. in International Relations and International Economics from the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY