Transforming the Prairie: Early Tree Planting in an Oklahoma Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTENSIVE LEVEL SURVEY of COLLEGE GARDENS HISTORIC DISTRICT, Stillwater, Oklahoma

INTENSIVE LEVEL SURVEY OF COLLEGE GARDENS HISTORIC DISTRICT, Stillwater, Oklahoma Project No. 03-404 Submitted by: Department of Geography Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 74078-4073 To: Oklahoma State Historic Preservation Office Oklahoma Historical Society 2704 Villa Prom Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73107 Project Personnel: Brad A. Bays, Principal Investigator John Womack, AJA ArchitecturalConsultant CONTENTS PART PAGE I. Abstract. II. Introduction ................ x III. Project Objectives .. .......... xx IV. Area Surveyed ............ xx V. Research Design and Methodology .. ....... xx VI. Survey Results .. ............ xx VII. Property Types .... ...................... xx VIII. Historic Context .. ............................... xxx IX. Annotated Bibliography ................... ... ... ..........................•. XXX X. Summary ... .... xxx XI. Properties Documented in the College Gardens Historic District ... ........... xxx 11 Abstract An intensive-level survey of the College Gardens residential area of Stillwater, Oklahoma was conducted during the 2002-03 fiscalyear under contract fromthe Oklahoma State Historic PreservationOffice (SHPO). Brad A. Bays, a geographer at Oklahoma State University, conducted the research. The survey involved a study area of87 acres in the western part of Stillwater as specifiedby the survey and planning subgrant stipulations prepared by the SHPO. The surveyresulted in the minimal level documentation of213 properties within the designated study area. Minimal level documentation included the completion of the Historic Preservation Resource Identification Form and at least two elevation photographs for each property. This document reportsthe findings of the survey and provides an analysis of these findingsto guide the SHPO's long term preservation planning process. This reportis organized into several parts. A narrative historic context of the study area from the date of earliest development ( 1927) to the mid-twentieth century (1955) is provided as a general basis for interpreting and evaluating the surveyresults. -

Literature on the Vegetation of Oklahoma! RALPH W· KELTING, Unberlltj of Tulia, Tulia Add WJL T

126 PROCEEDINGS OF THE OKLAHOMA Literature on the Vegetation of Oklahoma! RALPH W· KELTING, UnberlltJ of Tulia, Tulia aDd WJL T. PENFOUND, UnlYenlty of Oklahoma, Norman The original stimulus tor this bibliographic compilation on the vegeta tion of Oklahoma came from Dr. Frank Egler, Norfolk, Connecticut, who is sponsoring a series ot such papers for aU the states of the country. Oklahoma is especially favorable for the study· of vegetation since it is a border state between the cold temperate North and the warm temperature South, and between the arid West and the humid East. In recognition of the above climatic differences, the state has been divided into seven sec tions. The parallel of 35 degrees, 30 minutes North Latitude has been utiUzed to divide the state into northern and southern portions. The state has been further divided into panhandle, western, central, and eastern sections, by the use of the following meridians: 96 degrees W., 98 degrees ·W., and 100 degrees W. In all cases, county lines have been followed so that counties would not be partitioned between two or more sections. The seven sections are as follows: Panhandle, PH; N9rthwest, NW; Southwest, SW; North Central, NC; South Central, SC; Northeast, NE; and Southeast, SE (Figure 1). The various sections of the state have unique topographic features ot interest to the student of vegetation. These sections and included topo graphic features are as tollows: Panhandle: Black Mesa, high plains, playas (wet weather ponds); Northwest: Antelope Ht1Is, Glass Mountains, gypsum hUls, sand desert, Waynoka Dunes, salt plains, Great Salt Plains Reservoir; Southwest: gypsum hills, Wichita Mountains, Altus-Lugert Reservoir; North Central: redbed plains, sandstone hills, prairie plains; South Central: redbed plains, sandstone hUls, Arbuckle Mountains, Lake Texoma; Northeast: Ozark Plateau, Grand Lake;. -

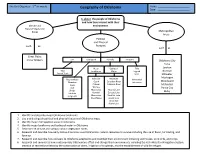

Geography of Oklahoma Name: ______2Nd Date: ______

The Unit Organizer: 2nd six weeks Geography of Oklahoma Name: _______________________ 2nd Date: _______________________ Is about the people of Oklahoma and how they interact with their Climate and environment. Natural Vegetation Zones Metropolitan Areas Political and Physical such as Features such as Great Plains Cross Timbers use distinguish identify interpret Oklahoma City Tulsa Major Bodies of Title Lawton Text Landforms Water Legend Norman Search Tools Scale Stillwater Muskogee Map symbols Arbuckle Red River Directional Woodward Direction Ozark Canadian River Indicators Scale Plateau Arkansas River McAlester Size Wichita Ponca City Shape Mountains Texoma Lake Bixby Latitude Kiamichi Eufaula Lake Longitude Mountains Tenkiller Lake Black Mesa Grand Lake Great Salt Plains Lake 1. Identify and describe major Oklahoma landmarks. 2. Use and distinguish political and physical features of Oklahoma maps. 3. Identify major metropolitan areas in Oklahoma. 4. Identify major landforms and bodies of water in Oklahoma. 5. Describe the climate and various natural vegetation zones. 6. Research and describe how early Native Americans used Oklahoma’s natural resources to survive including the use of bison, fur trading, and farming. 7. Research and describe how pioneers to Oklahoma adapted to and modified their environment including sod houses, wind mills, and crops. 8. Research and summarize how contemporary Oklahomans affect and change their environments including the Kerr-McLellan Navigation System, creation of recreational lakes by the construction of dams, irrigation of croplands, and the establishment of wildlife refuges. . -

Teacher's Guide

Destinations OklahomaTeacher's Guide Content for this educational program provided by: CIMC Students of All Ages: Your adventure is about to begin! Within these pages you will become a “Geo-Detective” exploring the six countries of Oklahoma. Yes, countries! Within Oklahoma you’ll be traveling to unique places or regions called “countries.” Maybe you’ve heard of “Green Country” with its forests and specialty crops, or “Red Carpet Country,” named for the red rocks and soil formed during the ancient Permian age. Each region or country you visit will have special interesting themes or features, plus fun and sometimes challenging activities that you will be able to do. You will notice each country or region can be identifi ed by natural, economic, historic, cultural, geographic and geological features. The three maps you see on this page are examples of maps you might need for future Geo-Explorations. As a Geo-Detective having fun with the following activities, you’ll experience being a geographer and a geologist at the same time! So for starters, visit these websites and enjoy your Geo-Adventure: http://education.usgs.gov http://www.ogs.ou.edu http://www.census.gov http://www.travelok.com/site/links.asp Gary Gress, Geographer Neil Suneson, Geologist Oklahoma Alliance for Geographic Education Oklahoma Geological Survey Teachers: PASS Standards met by Destinations Oklahoma are listed on pages 15 – 17. Indian Nations of Oklahoma 1889 - Before and after the Civil War, tribal boundaries were constantly changing due to U.S. government policies. Eventually the Eastern and Western tribes merged into a state called “Oklahoma,” meaning “(land of) red people.” Oklahoma's 10 Geographic Regions - These regions refl ect both physical features (topography) and soils. -

Universiv Micrxxilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microtllming. While the most advanced teehnology has been used to photograpii and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

The State of Oklahoma - an Introduction to the Sooner State from NETSTATE.COM

The State of Oklahoma - An Introduction to the Sooner State from NETSTATE.COM HOME INTRO The State of Oklahoma SYMBOLS ALMANAC ore than 50 languages are spoken in ECONOMY M GEOGRAPHY the state of Oklahoma. There are 55 STATE MAPS distinct Indian tribes that make the state PEOPLE their home, and each of these tribes has GOVERNMENT its own language or dialect. The colorful FORUM history of the state includes Indians, NEWS cowboys, battles, oil discoveries, dust COOL SCHOOLS storms, settlements initiated by offers of STATE QUIZ STATE LINKS free land, and forced resettlements of BOOK STORE entire tribes. MARKETPLACE NETSTATE.STORE Oklahoma, the Sooner State Oklahoma's Indian heritage is honored in NETSTATE.MALL its official state seal and flag. At the GUESTBOOK center of the seal is a star, and within CONTACT US each of the five arms of the star are symbols representing each of the five tribes (the "Five Civilized Tribes") that House Flags were forcefully resettled into the From $5.99 territory of Oklahoma. The tribes Great Selection. depicted on the seal are the Creeks, the Unbeatable Prices. Chickasaw, the Choctaw, the Cherokee, Flags For Every and the Seminoles. The present Season & Reason. www.discountdecorati… Oklahoma state flag depicts an Indian war shield, stars, eagle feathers, and an Indian peace pipe, as well as a white Find Birth man's symbol for peace, an olive branch. Records Online THE STATE NAME: 1) Search Birth Records for Free 2) Find the Oklahoma is a word that was made up by the native American missionary Allen Records Instantly! Birth.Archives.com Wright. -

Taxonomic and Ethnobotanical

TAXONOMIC AND ETHNOBOTANICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE VASCULAR FLORA OF OKLAHOMA By MARY ELIZABETH GARD Bachelor of Science in Botany Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2005 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 2009 TAXONOMIC AND ETHNOBOTANICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE VASCULAR FLORA OF OKLAHOMA Thesis Approved: Dr. Ronald J. Tyrl Thesis Adviser Dr. Terrence Bidwell Dr. Joseph Bidwell Dr. A Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS With regards to the Flora conducted, I wish to thank the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service for financial support of the OPNWR project, and OPNWR manager Steve Hensley for assistance in the initial stages of the OPNWR project. I wish to thank Trey Cowles and Cheryl Daniels for assistance in collecting specimens; Clayton Russell for providing lodging; Patricia Folley for assistance in identifying specimens of Carex ; Fumiko Shirakura for help with formatting labels; and Mike Palmer for editorial comments. With regards to the Tephrosia project,I am grateful to Dr. Becky Johnson for her comments and guidance and initiation of the project, J. Byron Sudbury for his help in the extraction process, Eahsan Shahriary for statistical assistance and Naomi Cooper for her assistance in conducting the bioassays. I thank my committee chairperson, Dr. Ron Tyrl, for guidance and assistance in every stage of this project. His suggestions have been very helpful in improving this work. I also wish to thank my other committee members Joe Bidwell and Terry Bidwell for their comments, perspective and guidance in this entire work. -

Thematic Survey of Historic Barns in Northeast Oklahoma

Thematic Survey of Historic Barns in Northeast Oklahoma Adair, Cherokee, Creek, Craig, Delaware, Mayes, McIntosh, Muskogee, Nowata, Okfuskee, Okmulgee, Osage, Ottawa, Pawnee, Rogers, Sequoyah, Tulsa, Wagoner, and Washington Counties Prepared for: OKLAHOMA HISTORICAL SOCIETY State Historic Preservation Office Oklahoma History Center 800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73105-7914 Prepared by: Brad A. Bays, Ph.D. Department of Geography 337 Murray Hall Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 74078-4073 2 Acknowledgement of Support The activity that is the subject of this survey has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. Nondiscrimination Statement This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity National Park Service 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20240 3 CONTENTS 4 5 6 I. ABSTRACT Under contract to the Oklahoma State Historic Preservation Office, Brad A. Bays of Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, conducted the Survey of Historic Barns in Northeastern Oklahoma (OK/SHPO Management Region Three) during the fiscal year 2012- 2013. -

UCO NOC Social Science 2019-2020

Transfer Agreement Between Northern Oklahoma College And University of Central Oklahoma Effective Academic Year: 2018-2019 Associate of Art- Social Science And Bachelor of Arts- History Bachelor of Arts in History-Museum Studies Bachelor of Arts - Geography Bachelor of Arts in Education- History Education Dr.{~er, c?atL---~ Department of History and Geography y ~~v-~ 2-tJ/ 7 Date Cl~w~J£n>, Darrell Frost, Division Chair Dr. Catherine Webster, Dean Social Science College of Liberal Arts Date J5t Pamela Stinson Dr. John Barthell, Provost Vice President for Academic Affairs Vice President for Academic Affairs S-I- .;2019 Date Date Page I of3 Transfer Agreement Nmthern Oklahoma College: A.A. Social Science And University of Central Oklahoma: BA Geography To comply with this agreement, students must complete the associate's degree with the major listed above and include the specific courses listed below. Courses listed here are required for the agreement. Credited courses complctcd as part of the A.A. or A.S. that do not apply to the general education at NOC or the UCO major transfer to UCO as electives. NOC UCO General Education requirements University Core completed with A.A or A.S. HIST 1483 or 1493 American History HIST 1483 or 1493 American History GEOG 2253 Regional Geography of the World GEO 2303 Regional Geography of the World SOC 1113 Principles of Sociolo2:v SOC 2103 Sociology The NOC "recommended courses" listed immediately To be used in Other Social Studies area. below are not required to be taken at NOC. POLI 2113 Comparative Political Issues POL 2713 Introduction to Comparative Politics HIST 1013 World Historv I HIST 1013 World Historv I HIST 1023 World Histmy II HIST 1023 World Historv II ECON 2113 Macroeconomics Principles ECON 1103 Introduction to Economics This clegree requires aclclitional course work, inclucling the general eclucation, as statecl in the NOC Catalog. -

Oklahoma State Dept. of Education, Oklahoma City

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 100 613 SE 014 453 AUTHOR Johnson, Kenneth S. TITLE Guidebook for Geologic Field Trips in Oklahoma (Preliminary Version). Book 1: Introduction, Guidelines, and Geologic History of Oklahoma. Educational Publication No. 2. INSTITUTION Oklahoma Geological Survey, Norman. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C.; Oklahoma Curriculum Improvement Commission, Oklahoma City.; Oklahoma State Dept. of Education, Oklahoma City. Curriculum Div. PUP DATE 71 NOTE 2f.1p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Earth Science; Field Studies; *Field Trips; Geology; *Program Descriptions; Science Activities; Science Education; *Secondary School Science IDENTIFIERS Oklahoma ABSTRACT This guidebook is designed to help a seAcolidary science teacher plan and conduct an earth science field trip in Oklahoma. It provides activities for students, information on pretrip planning, leading field trips, and safety measures to be followed. The guidebook also includes detailed information about the geologic history of Oklahoma complete with many detailed diagrams and illustrations. The periods of Geologic history are dealt with separately and in depth.(BR) OKLAHOMA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles J. Mankin, Director Educational Publication 2 U % 01118$1TMIENT Oi 111181.11, EDUCATION 4 WiLiAlle NATIONAL INSTITUTE Oi EDUCATION 'His DOCuMENT HAS SEEN REPRO DuC EP ETTACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANi:ATION ORIGIN AT1NG T POINTS OF yiENd OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY GUIDEBOOK FOR GEOLOGIC FIELD TRIPS IN OKLAHOMA (PRELIMINARY VERSION) BOOK I: INTRODUCTION, GUIDELINES, AND GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF OKLAHOMA KENNETH S1 JOHNSON 1971 A project supported by: 0 Oklahoma Geological* Survey National Science Foundation k.10 Oklahoma Curriculum Improvement Commission ki) and Curriculum Section of Instructional Division Oklahoma State Department of Education Leslie Fisher, .5tate igupgrintendent -ortrs, ,wroximately). -

Level IV Ecoregions of Oklahoma

Summary Table: Characteristics of the Ecoregions of Oklahoma 25. HIGH PLAINS 33. EAST CENTRAL TEXAS PLAINS Level IV Ecoregion Physiography Geology Soils Climate Vegetation Land Cover and Land Use Level IV Ecoregion Physiography Geology Soils Climate Vegetation Land Cover and Land Use Area Elevation/ Surfi cial and Bedrock Order (Great Group) Common Soil Series Temperature/ Precipitation Frost Free Mean Temperature Area Elevation/ Surfi cial and Bedrock Order (Great Group) Common Soil Series Temperature/ Precipitation Frost Free Mean Temperature (square Local Relief Moisture Mean annual Mean annual January min/max; (square Local Relief Moisture Mean annual Mean annual January min/max; miles) (feet) Regimes (inches) (days) July min/max (oF) miles) (feet) Regimes (inches) (days) July min/max (oF) 25b. Rolling Sand 800 Gently undulating to hummocky, sandy plains with sand 2400-4800/ Quaternary sand and silt deposits that were laid Alfi sols (Haplustalfs), Entisols Vona, Dalhart, Tivoli, Pratt. Rapidly Mesic/ 17-20. 175-185 Mostly 19/46 Potential natural vegetation: sand sagebrush–bluestem prairie. Today, on Dalhart fi ne sandy loams: Grassland, rangeland and, in suitable areas, irrigated 33a. Northern 364 Level to rolling plains. Extensive fl ats occur. In smaller 490-720/ Mostly mantled by Quaternary silt, clay, sand, and On uplands: Mollisols (Argiustolls, On uplands: Durant, Dennis, Thermic/ 42-45 230-235 29/51; Potential natural vegetation: tall grass prairie (dominants: big bluestem, little bluestem, switchgrass, Cropland, pastureland, and riparian forest. Primary crops Plains hills, depressions, and stabilized, partially stabilized, or 10-120 down by rivers, and subsequently reworked by wind. (Ustipsamments). permeable and moderately permeable Ustic More than (up to 19/50 in blue grama, buffalograss, sand dropseed, and sand bluestem dominate. -

Teaching with Sunset at Roman Nose State Park by Wilson Hurley

Teaching with Sunset at Roman Nose State Park by Wilson Hurley This document is designed to help teachers present, discuss, and teach about Oklahoma history and art literacy through the use of this work of art. The information and exercises here will aid in understanding and learning from this artwork. Contents: • First Analysis and Criticism • Overview of the Artwork • About the Artist • Details • Suggested Reading • Final Analysis • PASS Objectives Oklahoma Arts Council • Teaching with Capitol Art First Analysis and Criticism The steps below may be used for group discussion or individual written work. Before beginning the steps, take two minutes to study the artwork. Look at all the details and subject matter. After studying the artwork in silence, follow these steps: Describe: Be specific and descriptive. List only the facts about the objects in the painting or sculpture. • What things are in the artwork? • What is happening? • List what you see (people, animals, clothing, environment, objects, etc.). Analyze: • How are the elements of art – line, shape, form, texture, space, and value used? • How are the principles of design – unity, pattern, rhythm, variety, balance, emphasis, and proportion used? Interpretation: Make initial, reasonable inferences. • What do you think is happening in the artwork? • Who is doing what? • What do you think the artist is trying to say to the viewer? Evaluate: Express your opinion. • What do you think about the artwork? • Is it important? • How does it help you understand the past? • Do you like it? Why or why not? Oklahoma Arts Council • Teaching with Capitol Art Overview of the Artwork Sunset at Roman Nose State Park is one of four paintings in Wilson Hurley’s Visions of the Land: The Centennial Suite that represents the four quadrants of Oklahoma’s diverse landscape.