Edmond and the Territorial Normal School of Oklahoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oklahoma City's Drinking Water in a Struggling Watershed

Oklahoma City’s Drinking Water Keywords: planning - watershed & strategic, public health, restoration, in a Struggling Watershed stormwater, water quality The Oklahoma City Watershed Organization Name: The North Canadian River—a key component of Oklahoma City’s watershed—runs 441 miles from New Mexico to Central Oklahoma, where it joins the Canadian River and Lake Eufaula. Oklahoma City channels much of the river water into reservoir lakes, including Hefner and Overholser, which together with the other regional lakes, supply drinking water to the city and surrounding neighborhoods. The Oklahoma Water Resources Board, lakes are also stocked with popular fish, and residents use the lakes sub-grantee of the Oklahoma and river for recreational boating and rowing. Like most metropolitan Secretary of Energy and rivers, the North Canadian is highly engineered, its levels controlled Environment according to various demands, including water treatment, recreation, and maintenance of drinking water supplies. About the Organization: The mission of the Oklahoma Water Both Lake Hefner and Lake Overholser have a long history of Resources Board (OWRB) is to eutrophication, a harmful condition characterized by lack of oxygen, protect and enhance the quality of resulting in excessive algal growth and death of wildlife. Eutrophic life for Oklahomans by managing conditions are caused by nutrient-rich runoff from point sources (such and improving the state’s water as factories and sewage treatment plants) and non-point sources (such resources to ensure clean and reliable as stormwater carrying pollutants and agricultural fertilizers). water supplies, a strong economy, and a safe and healthy environment. Location: Oklahoma City, OK Contact Information: Chris Adams, Ph.D. -

North Canadian River Ranch 1,230 + Acres | Woodward County, Woodward, Ok

NORTH CANADIAN RIVER RANCH 1,230 + ACRES | WOODWARD COUNTY, WOODWARD, OK BRYAN PICKENS Partner/Broker Associate 214-552-4417 [email protected] REPUBLICRANCHES.COM NORTH CANADIAN RIVER RANCH The North Canadian River Ranch is an impeccable live-water hunting and recreational trophy property which stands out from other ranches on the market. It has diverse terrain, a terrific lodge on a serene setting complete with a top-notch grass airstrip, and is quiet, remote, and full of game and outdoor opportunities typical for this part of the state. This northwest Oklahoma ranch has an excellent blend of rolling sand hills, grassland meadows and productive cultivated areas, prime habitat for whitetail deer, bob white quail, and rio grande turkeys. Price: $2,850,000 Woodward County 1,230 +/-Acres Luxury log cabin hunting lodge 3 main pastures for cattle 4 water wells Whitetail deer, quail, abundant game 2 fishing ponds 2.3 miles of North Canadian River Improvements: The luxury log cabin hunting lodge was completely remodeled in 2008, complete with a new roof and exterior stone. It has approximately 4,400 sf of living space, and approximately 2,000 sf of porch area. The setup is excellent for large groups or families. 5 bedrooms, each with a full bath. (4 bedrooms + 1 master suite) Stone tile flooring, hand-scraped hardwoods, and granite countertops. Two geo thermal heating/cooling units. Covered porch overlooking the lake to the south. Screened in porch overlooking the lake to the south. High-end appliances and advanced water filtration system. Sprinklered irrigation system for the entire yard. -

INTENSIVE LEVEL SURVEY of COLLEGE GARDENS HISTORIC DISTRICT, Stillwater, Oklahoma

INTENSIVE LEVEL SURVEY OF COLLEGE GARDENS HISTORIC DISTRICT, Stillwater, Oklahoma Project No. 03-404 Submitted by: Department of Geography Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 74078-4073 To: Oklahoma State Historic Preservation Office Oklahoma Historical Society 2704 Villa Prom Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73107 Project Personnel: Brad A. Bays, Principal Investigator John Womack, AJA ArchitecturalConsultant CONTENTS PART PAGE I. Abstract. II. Introduction ................ x III. Project Objectives .. .......... xx IV. Area Surveyed ............ xx V. Research Design and Methodology .. ....... xx VI. Survey Results .. ............ xx VII. Property Types .... ...................... xx VIII. Historic Context .. ............................... xxx IX. Annotated Bibliography ................... ... ... ..........................•. XXX X. Summary ... .... xxx XI. Properties Documented in the College Gardens Historic District ... ........... xxx 11 Abstract An intensive-level survey of the College Gardens residential area of Stillwater, Oklahoma was conducted during the 2002-03 fiscalyear under contract fromthe Oklahoma State Historic PreservationOffice (SHPO). Brad A. Bays, a geographer at Oklahoma State University, conducted the research. The survey involved a study area of87 acres in the western part of Stillwater as specifiedby the survey and planning subgrant stipulations prepared by the SHPO. The surveyresulted in the minimal level documentation of213 properties within the designated study area. Minimal level documentation included the completion of the Historic Preservation Resource Identification Form and at least two elevation photographs for each property. This document reportsthe findings of the survey and provides an analysis of these findingsto guide the SHPO's long term preservation planning process. This reportis organized into several parts. A narrative historic context of the study area from the date of earliest development ( 1927) to the mid-twentieth century (1955) is provided as a general basis for interpreting and evaluating the surveyresults. -

How Did Law, Order, and Growth Develop in Oklahoma?

Chapter How did law, order, and growth develop 10 in Oklahoma? Where did the name “Oklahoma” originate? In 1866, the U.S. and Five Civilized Tribes signed the Reconstruction treaties. That was when Choctaw Chief Allen Wright coined the word “Oklahoma.” He made it from two Choctaw words, “okla” and “humma,” meaning “Land of the Red Man.” He meant it for the eastern half of Indian Terri- tory, the home of the five tribes. In later years, however, “Oklaho- ma country” became the common name for the Unassigned Lands. It was 1890 when the western half of the old Indian Territory became the Territory of Oklahoma. What was provisional government? On April 23, 1889, the day after the Land Run, settlers met in Oklahoma City and Guthrie to set up temporary governments. Other towns followed suit. Soon all the towns on the prairie had a type of skeleton government, usually run by a mayor. Homesteaders also chose town marshals and school boards. They chose committees to resolve dispute over land claims. Sur- veyors mapped out Guthrie and Oklahoma City. There were dis- putes about an unofficial government making official property Allen Wright Oklahoma Historical lines, but, later, the surveys were declared legal. Today, they remain the Society basis for land titles in those cities. The temporary or provisional governments were indeed “unof- ficial.” They succeeded only because the majority of people agreed to their authority. Not everyone agreed, however, and crime was hard to control. Often troops from Fort Reno closed the gap between order and disorder. The army’s presence controlled violence enough to keep set- tlers there. -

North Canadian River

NONPOINT SOURCE SUCCESS STORY Protecting and RestoringOklahoma the North Canadian River, Oklahoma City’s Water Supply, Through Voluntary Conservation Programs Waterbody Improved High bacteria concentrations resulted in the impairment of the North Canadian River and placement on Oklahoma’s Clean Water Act (CWA) section 303(d) list of impaired waters in 2006. Pollution from grazing, hay production and cropland areas contributed to this impairment. Implementing conservation practice systems (CPs) to promote improved grazing and cropland management decreased bacteria levels in the creek. As a result, a segment of the North Canadian River was removed from Oklahoma’s 2016 CWA section 303(d) list for Escherichia coli. Portions of the North Canadian River now partially support its primary body contact (PBC) designated use. Problem The North Canadian River is a 441-mile stream flowing from New Mexico and Texas before it flows into Lake Eufaula in eastern Oklahoma. Poor management of grazing and cropland contributed to listing a 105.34- mile segment as impaired for E. coli in 2006 when the geometric mean of samples collected during the recreational season was 135 colony forming units/100 milliliters (CFU/100 mL) (Figure 1). The PBC recreation designated use is impaired if the geometric mean of E. coli exceeds 126 CFU/100 mL. Oklahoma added this North Canadian River segment (OK520530000010_10) to the 2006 section 303(d) list for nonattainment of its PBC designated beneficial use. Land use in the 760-square-mile watershed of the listed segment is approximately 41 percent row crop, which is used almost exclusively for winter wheat production. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

Oklahoma Agencies, Boards, and Commissions

ABC Oklahoma Agencies, Boards, and Commissions Elected Officers, Cabinet, Legislature, High Courts, and Institutions As of September 10, 2018 Acknowledgements The Oklahoma Department of Libraries, Office of Public Information, acknowledges the assistance of the Law and Legislative Reference staff, the Oklahoma Publications Clearing- house, and staff members of the agencies, boards, commissions, and other entities listed. Susan McVey, Director Connie G. Armstrong, Editor Oklahoma Department of Libraries Office of Public Information William R. Young, Administrator Office of Public Information For information about the ABC publication, please contact: Oklahoma Department of Libraries Office of Public Information 200 NE 18 Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73105–3205 405/522–3383 • 800/522–8116 • FAX 405/525–7804 libraries.ok.gov iii Contents Executive Branch 1 Governor Mary Fallin ............................................3 Oklahoma Elected Officials ......................................4 Governor Fallin’s Cabinet. 14 Legislative Branch 27 Oklahoma State Senate ....................................... 29 Senate Leadership ................................................................ 29 State Senators by District .......................................................... 29 Senators Contact Reference List ................................................... 30 Oklahoma State House of Representatives ..................... 31 House of Representatives Leadership .............................................. 31 State Representatives by District -

Indian Territory -- 1866- 1889

Page 6 The Cherokee and other Tribal governments post 1866, became in effect "caretaker" governments having the burden of car rying out the dicta included in the 1866 treaties. It was like a government, held in "trusteeship" - truly "domestic dependent nations". Land assignments to the various tribes , including the permissive occupation by other covered tribes of previously assigned lands is shown: No Man’s Land 1. CHEYENNE AND ARAPAHO 2. WICHITA .AND CADDO 3. COMANCHE. KIOWA AND APACHE 4. CHICKASAW 5. POTTAWATOMIE AND SHAWNEE 6. KICKAPOO 7. IOWA 8. 0T0 AND MISSOURI 9. PONCA 10. TONKAWA 11. kaw Indian Territory, 12. o s a g e 1866 to 1889 13. PAWNEE 14. SAC AND FOX 15. SEMINOLE 16. CHOCTAW 17. CREEK 18. CHEROKEE 19. SENECA. WYANDOTTE. SHAWNEE. OTTAWA. MODOC. PEORIA AND QL’AP.AW INDIAN TERRITORY -- 1866- 1889 this map reflects the Tribal land allocations that resulted from the past-war treaties with the United States. In addition to expected woes to flow from railroad rights of way, various cattle and other trails were to criss-cross the Indian Territory and further complicate land usage and the security of the designated owners. By a Treaty of June 7, 1869 the Shawnees were included in the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokees attempted to collect grazing fees for cattle that were bei n g driven from Texas to the north. In 1883 it was apparent that they could not collect the fees. The land designated as the "Cherokee Outlet" was leased to a Kansas cattlemen's combine for $100,000 per year. The income was used to develop an educational, system which by 1870 had 69 separate schools. -

Hydrogeology and Water Quality of the North Canadian River Alluvium, Concho Reserve, Canadian County, Oklahoma______

HYDROGEOLOGY AND WATER QUALITY OF THE NORTH CANADIAN RIVER ALLUVIUM, CONCHO RESERVE, CANADIAN COUNTY, OKLAHOMA__________ By Carol J. Becker U. S. DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 97-657 Prepared in cooperation with the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 1998 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THOMAS J. CASADEVALL, Acting Director Any use of trade names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not impiy endorsement by the U.S. Government. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: OKLAHOMA CITY 1998_____ For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Water Resources Division Box 25286 202 NW 66th Street, Building 7 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Oklahoma City, OK 73116 CONTENTS Abstract..........................................................^^ Introduction ..........................................._^ Purrwse and Scope................................................^ Acknowledgments..................................................................................^^ Description of stody area...................................................................................................................................» Methods of study................................................................................................................................................. Seismic-Refraction -

MEDFORD, OKLAHOMA, 1919-1940 by DEBRA DOWNING Bachelor of Arts Southern Nazarene

AGRICULTURAL CONDITIONS IN THE SOUTHERN PLAINS: MEDFORD, OKLAHOMA, 1919-1940 By DEBRA DOWNING Bachelor of Arts Southern Nazarene University Bethany, Oklahoma 1995 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1997 AGRICULTURAL CONDITIONS IN THE SOUTHERN PLAINS: MEDFORD, OKLAHOMA, 1919-1940 Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii PREFACE The history of a small farming community such as Medford, Oklahoma, is significant to western history for a number of reasons. Medford developed as a typical southern plains town, experiencing boom and bust cycles, and growth and decline. Market, weather, and population patterns affected the prosperity of the town, and as such are good examples of how these phenomena affected a rural, agricultural community in the Southern Plains. Land hungry pioneers established Medford during the Cherokee Strip land rush of 1893. This land rush opened additional Indian lands to white settlement. Overnight the prairie became towns and farms as thousands of eager and optimistic souls sought their future on free lands. Most of these people either had a farming background or aimed to acquire one. The land was only marginally suitable for agriculture during some years, and in fact the United States government had sent explorers into the region early in the nineteenth century, and these men had labeled the region the Great American Desert. Medford residents would learn just what this label meant as they plowed iii up the ground and sought to feed their families and build homes. An agricultural boom occurred in the United States during World War I, as the demand for food to support the war effort, and the mechanization of agriculture, prompted what some have called the great plow-up. -

Literature on the Vegetation of Oklahoma! RALPH W· KELTING, Unberlltj of Tulia, Tulia Add WJL T

126 PROCEEDINGS OF THE OKLAHOMA Literature on the Vegetation of Oklahoma! RALPH W· KELTING, UnberlltJ of Tulia, Tulia aDd WJL T. PENFOUND, UnlYenlty of Oklahoma, Norman The original stimulus tor this bibliographic compilation on the vegeta tion of Oklahoma came from Dr. Frank Egler, Norfolk, Connecticut, who is sponsoring a series ot such papers for aU the states of the country. Oklahoma is especially favorable for the study· of vegetation since it is a border state between the cold temperate North and the warm temperature South, and between the arid West and the humid East. In recognition of the above climatic differences, the state has been divided into seven sec tions. The parallel of 35 degrees, 30 minutes North Latitude has been utiUzed to divide the state into northern and southern portions. The state has been further divided into panhandle, western, central, and eastern sections, by the use of the following meridians: 96 degrees W., 98 degrees ·W., and 100 degrees W. In all cases, county lines have been followed so that counties would not be partitioned between two or more sections. The seven sections are as follows: Panhandle, PH; N9rthwest, NW; Southwest, SW; North Central, NC; South Central, SC; Northeast, NE; and Southeast, SE (Figure 1). The various sections of the state have unique topographic features ot interest to the student of vegetation. These sections and included topo graphic features are as tollows: Panhandle: Black Mesa, high plains, playas (wet weather ponds); Northwest: Antelope Ht1Is, Glass Mountains, gypsum hUls, sand desert, Waynoka Dunes, salt plains, Great Salt Plains Reservoir; Southwest: gypsum hills, Wichita Mountains, Altus-Lugert Reservoir; North Central: redbed plains, sandstone hills, prairie plains; South Central: redbed plains, sandstone hUls, Arbuckle Mountains, Lake Texoma; Northeast: Ozark Plateau, Grand Lake;. -

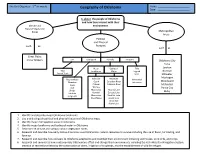

Geography of Oklahoma Name: ______2Nd Date: ______

The Unit Organizer: 2nd six weeks Geography of Oklahoma Name: _______________________ 2nd Date: _______________________ Is about the people of Oklahoma and how they interact with their Climate and environment. Natural Vegetation Zones Metropolitan Areas Political and Physical such as Features such as Great Plains Cross Timbers use distinguish identify interpret Oklahoma City Tulsa Major Bodies of Title Lawton Text Landforms Water Legend Norman Search Tools Scale Stillwater Muskogee Map symbols Arbuckle Red River Directional Woodward Direction Ozark Canadian River Indicators Scale Plateau Arkansas River McAlester Size Wichita Ponca City Shape Mountains Texoma Lake Bixby Latitude Kiamichi Eufaula Lake Longitude Mountains Tenkiller Lake Black Mesa Grand Lake Great Salt Plains Lake 1. Identify and describe major Oklahoma landmarks. 2. Use and distinguish political and physical features of Oklahoma maps. 3. Identify major metropolitan areas in Oklahoma. 4. Identify major landforms and bodies of water in Oklahoma. 5. Describe the climate and various natural vegetation zones. 6. Research and describe how early Native Americans used Oklahoma’s natural resources to survive including the use of bison, fur trading, and farming. 7. Research and describe how pioneers to Oklahoma adapted to and modified their environment including sod houses, wind mills, and crops. 8. Research and summarize how contemporary Oklahomans affect and change their environments including the Kerr-McLellan Navigation System, creation of recreational lakes by the construction of dams, irrigation of croplands, and the establishment of wildlife refuges. .