Hindutva Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

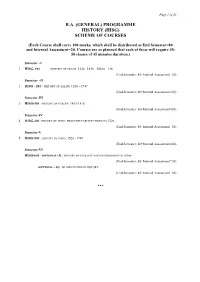

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, Pp 232

Book Discussion Dilip K Chakrabarti: The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, pp 232 Understanding Indian Borderlands Dilip K Chakrabarti he Indian subcontinent shares borders with Iran, Afghanistan, the plateau of Tibet Tand Myanmar. The sub-continent’s influence extends beyond these borders, creating distinct ‘borderlands’ which are basically geographical, political, economic and religious interaction zones. It is these ‘borderlands’ which historically constitute the subcontinent’s ‘area of influence’ and underlines its civilizational role in the Asian landmass. A clear understanding of this civilizational role may be useful in strengthening India’s perception of her own geo-strategic position. Iran One may begin with Iran at the western limit of these borderland. There are two main mountain ranges in Iran : the Zagros which separates Iran from Iraq and has to its south the plain of Khuzestan giving access to south Iraq ; and the Elburz which separates the inland Iran from the Caspian belt, Turkmenistan and (to a limited extent , Azerbaijan). The Caspian shores form a well-wooded verdant belt which poses a strong contrast to the dry Iranian plateau. There are two deserts inside the Iranian plateau -- dasht-i-lut and dasht-i-kevir, which do not encourage human habitation. The population concentration of Iran is along the margins of the mountain belt and also in Khuzestan. The following facts are noteworthy. The eastern rim of Iran carries an imprint of the subcontinent. There is a ready access to Iranian Baluchistan through the Kej valley in Pakistani Baluchistan. At its eastern edge this valley leads both to lower Sindh and Kalat. -

Magazine-2-3.Qxd (Page 2)

SUNDAY, AUGUST 30, 2015 (PAGE-3) SACRED SPACE BOOK REVIEW Upanishads Rediscovering Hinduism in the Himalayas Surinder Koul sacerdotal rites. Description about several obliterated sculptures of Source of Spirituality Albeit, the writer is professionally medical doctor, who often trav- images of Hindu Goddess and Gods , carved pillars, floral designs els to Arunachal Pradesh, the remotest part of the country and other on plinth slabs, full lotus carved on circular stone slab in Malinithan R C Kotwal Rajasthan and M.P. of present day India. places, out of her inquisitiveness and yearning to study cultural and temple premises are mentioned in minute details . Book also car- The exact numbers of the Upanishads are not clearly architectural sites in the country, yet she has produced the book as ries out various performances of worshipping that was prevalent in Upanishads means the inner or mystic teaching. The term known. Scholars differ on the total number of Upanishads as an intellectual fallow for interested people to undertake further deep main land India among the Hindus and had been practiced by the research about cultural heritage, sociological and environmental people in Arunachal Pradesh also from ages. It has identified tem- "Upanishad" is derived from Upa(Near) , ni ( down) and shad well as what constitutes an Upanishad. Some of the Upan- (to sit) i.e sitting down near. Groups of pupils sit near the aspects of earlier called NEFA now lately rechristened as Arunachal ples precincts and ruins where worshipping of Shiva Linga, worship- ishads are very ancient, but some are of recent origin. Pradesh. This region Arunachal Pradesh, had remained neglected ping of Durga as Malini still exist and on auspicious occasion devo- teacher to learn from him the secret doctrine. -

History of Śākta Pīthas in Assam (Upto 18Th Century)

HISTORY OF ŚĀKTA PĪTHAS IN ASSAM (UPTO 18TH CENTURY) An Abstract Submitted to Assam University, Silchar, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in History Submitted by Rumi Patar Ph. D. Registration No: Ph. D/1482/2011 Date - 19.04.2011 Supervisor Dr. Projit Kumar Palit Professor Department of History DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY JADUNATH SARKAR SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE ASSAM UNIVERSITY, SILCHAR 2015 History of Śākta Pîthas in Assam (upto 18th Century) Śȃkta pîthas are the seat or abode of the Goddess in Her different manifestations at different places. There is a legend related to the origin of the Śākta pîthas in Kȃlikȃ Purȃna, Yoginî Tantra, in the Epic Mahȃbhȃrata and in many religious literatures. Assam has been considered as the suitable place of worshipping the Goddess Śakti in various forms since time immemorial. Nobody can ascertain the exact date of the prevalence of Śakti worship in Assam. But some scholars ascertain that Śakti worship started in Assam from the pre-historic time. However many scholars are of the opinion that Naraka was the first Śȃkta worshipper in Assam who was the staunch follower of the then residing deity Kȃmȃkhyȃ. The most striking characteristic of ancient Assam (Prȃgjyotisha-Kȃmarūpa) was the Śakti cult which was the dominant and influential cult of Assam in the early period. It has been worshipped in different forms at different places in different times. Various literary evidence, inscriptions and sculptures of Assam are regarded as the most reliable sources which supply us authentic information about the prevalence of Śakti cult and its various forms even down to the Ahom rule upto 18th century CE. -

History Syllabus

SYLLABUS OF THREE YEAR DEGREE COURSE (Semester Pattern) Subject: - HISTORY (ELECTIVE AND CORE) NORTH LAKHIMPUR COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) B.A. (GENERAL/ ELECTIVE) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HIS) 1 SCHEME OF COURSES SEMES COURSE CODE TER THEORY COURSE TITLE L T P I ET-5-HIS-101 HISTORY OF ASSAM 1228 5 4 1 0 TO1826. II ET-5-HIS-201 HISTORY OF ASSAM 1826 TO 5 4 1 0 1947. III ET-5-HIS-301 HISTORY OF 5 4 1 0 INDIA (FROM EARLIEST TIME TO 1526) IV ET-5-HIS-401 HISTORY OF EUROPE (FROM 5 4 1 0 1453-1815 A.D.) V ET-3-HIS-501 HISTORY OF INDIA 3 2 1 0 (1200 - 1526) ET-4-HIS-502 HISTORY OF INDIA 4 3 1 0 (1526 - 1707) VI ET-4-HIS-601 HISTORY OF INDIA: POLITY, 4 3 1 0 SOCIETY AND ECONOMY (FROM 1707 to 1947 A.D.) ET-3-HIS-602 INDIAN NATIONALISM AND 3 2 1 0 FREEDOM STRUGGLE THE PROPOSED NEW SYLLABUS OF HISTORY FOR THE B.A. THREE-YEAR DEGREE COURSE IN THE SEMESTER SYSTEM 2 North Lakhimpur College (Autonomous) (As recommended by the Board of Studies in History in its meeting held on 11-09- 2013 and approved by the meeting of the Under Graduate Board held on _______) Course Structure Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45-60 Classes shall be of 60 minutes duration ELECTIVE SUBJECT: First Semester Second Semester Third Semester Fourth Semester Fifth Semester Sixth Semester COURSE: I COURSE:II COURSE:III COURSE: IV COURSE: V COURSE: VI (ET-5-HIS-101) (ET-5-HIS-201) (ET-5-HIS-301) (ET-5-HIS-401) (ET-3-HIS-501) (ET-4-HIS-601) History of History of Assam HISTORY OF HISTORY OF HISTORY OF HISTORY OF Assam 1228 1826 to 1947. -

1.6 Impacts of Tourism

PREFACE In the curricular structure introduced by this University for students of Post Graduate Diploma programme, the opportunity to pursue Post Graduate Diploma course in subjects introduced by this University is equally available to all learners. Instead of being guided by any presumption about ability level, it would perhaps stand to reason if receptivity of a learner is judged in the course of the learning process. That would be entirely in keeping with the objectives of open education which does not believe in artificial differentiation. Keeping this in view, study materials of the Post Graduate level in different subjects are being prepared on the basis of a well laid-out syllabus. The course structure combines the best elements in the approved syllabi of Central and State Universities in respective subjects. It has been so designed as to be upgradable with the addition of new information as well as results of fresh thinking and analysis. The accepted methodology of distance education has been followed in the preparation of these study materials. Co-operation in every form of experienced scholars is indispensable for a work of this kind. We, therefore, owe an enormous debt of gratitude to everyone whose tireless efforts went into the writing, editing and devising of a proper lay-out of the materials. Practically speaking, their role amounts to an involvement in invisible teaching. For, whoever makes use of these study materials would virtually derive the benefit of learning under their collective care without each being seen by the other. The more a learner would seriously pursue these study materials the easier it will be for him or her to reach out to larger horizons of a subject. -

Gazetteer of India, Arunachal Pradesh- East Siang & West Siang Districts

Gazetteer of India ARUNiD^AL PRADESh East Siang & West Siang Districts GAZETTEER OF INDIA A runachal Pradesh EAST SIANG AND WEST SIAIVO DISTRICTS A runachal Pradesh DISTRICT GAZETTEERS EAST SIANG AND WEST SIANG DISTRICTS By S.Dutta Choudhury Former Editor GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1994 Price : Ks, I70*OD Compiled by Shri C.K. S h y ^ , Compiler (Gazetteers) Arunachal Pradesh ^^ioUmen4 Cover-design and art-ivork^ By SBri (Bagcfu, formtrCy A rt T ^ e r t , (Directorate o f Information and ^uBCic (Relations, Qovemment of Arunacfud ^PradesB. Printed at: Sree Guru Press, Maligaon, Guwahati - 781011, « 570866 TTH 'Mel RAJ BHAVAN ITANAGAR -791tt FOREWORD This is indeed a very happy occasion for me to present the East Siang and West Siang Districts Gazetteer to the people of Arunachal Pradesh. It is a complete document giving physical and historical features of the State. (3 This Volume covers a wide range of Subjects. The development so far in various fields, and changes that have taken place in political, social, economic and cultural spheres over the years in these districts have been reflected in this document. I hope, this would prove useful to the scholars, educationists, researchers and administrators; and all those who are keen to know in detail about the socio-economic transformation which these districts have been undergoing in the recent years. PREFACE X he present volume is the fourth in the series of Arunachal Pradesh District Gazetteers. With the promulgation of Arunachal Pradesh (Reorganisation of Districts) Act, 1980 (Act No.3 of 1980) from June 1,1980, the Siang District has been divided into two new districts - East Siang District and West Siang District. -

(Dr.) BD Mishra

GOVERNOR’S SECRETARIAT ARUNACHAL PRADESH ITANAGAR PRESS RELEASE The Governor of Arunachal Pradesh Brig.(Dr.) B.D. Mishra (Retd.) visited Likabali in Lower Siang District on 23 rd March 2018. Interacting with the officers, the Governor emphasised of proper implementation of development plans and projects and utilization of allocated fund. He advised the officers to ensure transparency, accountability, continuity, audit and review and where ever required midterm correction. He also asked them to be less dependent on file works but on direct contact. Go out of your offices and reach out to the people, he said. The Governor asked the officials to motivate people for successful implementation of Goods and Services Tax, Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, Deen Dayal Upadhyay Gramjyoti Yojana, agriculture and horticulture programmes. Expressing his concern about the security of general public and particularly girls, the Governor stressed on proper measures to ensure foolproof safety and security for all. He emphasised on basic policing work, FIR registrations and correct enquiries and impartial and merit recruitment process. Lower Siang District Deputy Commissioner, Shri A.K Singh and Superintendent of Police Shri Sinjatla Singpho briefed the Governor about the status of the Central and State Government sponsored programmes in the district. The Governor also met the officers of 56 Div at Likabali. Deputy GOC, 56 Div Brig. Ajay Pasbola briefed the Governor about recent recruitment rally and security status. The Governor, who is on a day-long visit to Lower Siang District visited the Malinithan, one of the famous religious places in the State on the day. Accompanied by the First Lady of the State Smt Neelam Misra, he paid obeisance at the Malini temple and visited different parts of the archaeological site. -

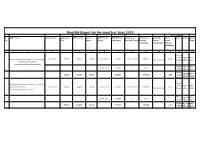

Monthly Report for the Month of June 2019 (Rs

Monthly Report for the month of June 2019 (Rs. In lakhs) Sl. NEC Project Sanction date Approved NEC's share State's NEC Release NEC Release Utilization Utilization Schedule State State Sector Major No. Cost share (Date) (Amount) Receive (Date) Receive date of share Head (Amount) completion release (Amount) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Aruna chal Agri & MH- 16-12-2014 497.80 448.02 49.78 16-12-2014 179.21 10-02-2016 179.21 9.95 Promotion and Development of Cash Crop 31-12-2017 Prades Allied 3601 1 in Arunachal Pradesh h (Location: Lower Subansiri dist) Aruna Agri & MH- 30-01-2018 179.20 0 0.00 chal Allied 3601 Prades Aruna Agri & MH- 497.80 448.02 49.78 358.41 179.21 9.95 chal Allied 3601 Prade Aruna Strengthening of central hatchery, Nirjuli, chal Agri & MH- 2 Arunachal Pradesh 17-12-2014 382.41 344.17 38.24 17-12-2014 137.67 01-09-2017 137.67 0.00 31-03-2016 Prades Allied 3601 (Location: Papum Pare dist) h Aruna Agri & MH- 26-04-2018 137.67 0 0.00 chal Allied 3601 Prades Aruna Agri & MH- 382.41 344.17 38.24 275.34 137.67 0.00 chal Allied 3601 Prade Development of Sericulture in Arunachal Aruna Pradesh. chal Agri & MH- 3 (Locations: Papum Pare, East Siang. Siang, 05-02-2016 696.75 627.07 69.68 05-02-2016 250.82 09-02-2018 250.82 25.08 28-02-2019 Prades Allied 3601 West Siang, Lower Sunbansiri & Upper h Subansiri dists) Aruna Agri & MH- 22-03-2018 250.82 0 0.00 chal Allied 3601 Prades Aruna chal Agri & MH- 696.75 627.07 69.68 501.64 250.82 25.08 Prade Allied 3601 sh Cultivation of Large cardamom in various Aruna districts of Arunachal -

![History [2017]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5140/history-2017-5985140.webp)

History [2017]

SYLLABUS DIBRUGARH UNIVERSITY THREE YEAR DEGREE PROGRAMME (Under CBCS) HISTORY [2017] 1 Details of Courses Under Undergraduate Programme (B.A) History Course *Credits ========================================================= Course Credit Tutorial I. Core Course 14X4= 56 14X1=14 (56+14=70 Credits (14 Papers) II. Elective Course (8 Papers) Discipline Specific Elective 4x4=16 4X1=4 (16+4=20 Credits) (Any Four) Generic Elective 4X4=16 4X1=4 (16+4=20 Credits) (Interdisciplinary) (Any Four) III. Ability Enhancement Courses 1. Ability Enhancement Compulsory Courses (AECC) 2 X 2=4 2 X 2=4 (4+4=8 Credits) (2 Papers of 2 credits each) Environmental Science English Communication/MIL 2. Ability Enhancement Courses 2 X 2=4 2 X 2=4 (4+4=8 Credits) (Skill based) (4 Papers of 2 credits each) _________________ Total credit= 128 2 Structure of B.A. CBCS (Hons) History Course of Dibrugarh University, 2017 Core Course (14) Paper I: History of India-I Paper-II: Social Formations and Cultural Patterns of the Ancient World Paper III: History of India-II Paper IV: Social Formations and Cultural Patterns of the Medieval World Paper V: History of India-III (c. 750-1206) Paper VI: Rise of the Modern West-I Paper VII: History of India IV (c.1206-1550) Paper VIII: Rise of the Modern West -11 Paper IX: History of India-V (c. 1550-1605) Paper X: History of India-VI (c. 1605-1750) Paper XI: History of Modern Europe- I (c. 1780-1939) Paper XII: History of India-VII (c. 1750-1857) Paper XIII: History of India-VIII (c. 1857-1950) Paper XIV: History of Modern Europe- II -

14. Archaeology in North-East India

ARCHAEOLOGYIN NORttH― EASTiND:A Archaeologv in North-East lndia: The Post-lnd ependence scenario GAUTAM SENGUPTAAND SUKANYA SHARMA ABSTRACT The archaeological record of north-east lndia is distinctive in character. lt is a synthesis of two types of cultural traits: lndian and South-east Asian. Archaeological findings from the region known as Assam in the pre-lndependence period were reported from the beginning of the nineteenth century, but archaeological work was mainly done by enthusiastic administrators or tea planters who were interested in antiquities. The post- lndependence period is marked by problem-oriented research, with institutional involvement, in archaeology. But, till date, none of the universities in the region have an exclusive department of archaeology. The archaeology of the post-lndependence period in north-east lndia can be considered a social phenomenon in a particular historical context. lt is now widely recognized that all archaeology is political in that it involves relations of power and contemporary interventions in the production of the past. A new perspective in archaeology, 'the archaeology of the contemporary past', acknowledges a clear role for archaeology in bringing to light those aspects of history and contemporary erxperience that are explicily hidden from the public view by centres of authority, or are obscured by the absence of authority among individuals and groups within the political arena. This is referred to as 'presencing the absence'. lt is time for presencing the absence in north-east lndia -

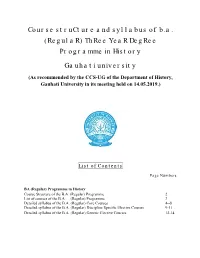

Three Year Degree Programme in History Gauhati University

Course struCture and syllabus of b.a. (RegulaR) ThRee YeaR DegRee Programme in History Gauhati university (As recommended by the CCS-UG of the Department of History, Gauhati University in its meeting held on 14.05.2019.) List of Contents Page Numbers BA (Regular) Programme in History Course Structure of the B.A. (Regular) Programme 2 List of courses of the B.A. (Regular) Programme 3 Detailed syllabus of the B.A. (Regular) Core Courses 4--8 Detailed syllabus of the B.A. (Regular) Discipline Specific Elective Courses 9-11 Detailed syllabus of the B.A. (Regular) Generic Elective Courses 12-14 Course Structure and Syllabus for B.A. (Regular) Three Year Degree Programme in History, Gauhati University as recommended by the CCS-UG of the Department of History, Gauhati University in its meeting held on 14.05.2019. COURSE STRUCTURE Semester Core Course (4) Ability Enhancement Skilled Enhancement Elective: Elective: Compulsory Courses Course (SEC) (2) Discipline Specific Generic (GE) (2) (AEC) (2) (DSE) (2) HIS –RC-1016: History of India from (English/MIL I Earliest Times up to c. Communication)/ 1206 Environmental Science II HIS –RC-2016: Environmental Science Early Assam upto c.1228 (English/MIL Communication)/ III HIS –RC-3016: HIS –SE-3014: History of India from c. Historical Tourism in 1206 to 1757 North East India IV HIS –RC-4016: HIS –SE-4014: History of Assam (c. Oral Culture and Oral 1228- 1826) History V SEC (from other HIS –RE-5016 HIS –RG-5016 department) History of India ( c. History of Europe 1757 - 1947) (c. 1648 – 1870) VI SEC (from other HIS –RE-6016 HIS –RG-6016 department) History of Assam (c.