14. Archaeology in North-East India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 53382-001 May 2021 Bangladesh: South Asia Sub regional Economic Cooperation Dhaka-Sylhet Corridor Road Investment Project Main report vol. 1 Prepared by the Roads and Highways Division, Bangladesh, Dhaka for the Asian Development Bank. Page i Terms as Definition AASHTO American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials ADB Asian Development Bank AMAN Rice (grown in wet season) APHA American Public Health Association ARIPA Acquisition and Requisition of Immoveable Property Act As Arsenic BD Bangladesh BIWTA Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Authority BNBC Bangladesh National Building Code BOQ Bill of Quantities Boro Rice (grown in dry season) BRTA Bangladesh Road Transport Authority BWDB Bangladesh Water Development Board CITES Convention on Trade in Endangered Species CO Carbon Monoxide CoI Corridor of Impact CPRs Community Property Resources DMMP Dredged Material Management Plan DC Deputy Commissioner DO Dissolved Oxygen DoE Department of Environment DoF Department of Forest EA Executive Agency ECA Environmental Conservation Act ECR Environmental Conservation Rules EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EMoP Environmental Monitoring Plan Engineer The construction supervision consultant/engineer EPAS Environmental Parameter Air Sampler EPC Engineering Procurement and Construction EQS Environmental Quality Standards ESCAP Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific ESSU Environmental and Social Safeguards Unit FC Faecal Coliform -

West Tripura District, Tripura

कᴂद्रीय भूमि जल बो셍ड जल संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण विभाग, जल शक्ति मंत्रालय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Ministry of Jal Shakti Government of India AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF GROUND WATER RESOURCES WEST TRIPURA DISTRICT, TRIPURA उत्तर पूिी क्षेत्र, गुिाहाटी North Eastern Region, Guwahati GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD REPORT ON “AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN OF WEST TRIPURA DISTRICT, TRIPURA” (AAP 2017-18) By Shri Himangshu Kachari Assistant Hydrogeologist Under the supervision of Shri T Chakraborty Officer In Charge, SUO, Shillong & Nodal Officer of NAQUIM, NER CONTENTS Page no. 1. Introduction 1-20 1.1 Objectives 1 1.2 Scope of the study 1 1.2.1 Data compilation & data gap analysis 1 1.2.2 Data Generation 2 1.2.3 Aquifer map preparation 2 1.2.4 Aquifer management plan formulation 2 1.3 Approach and methodology 2 1.4 Area details 2-4 1.5Data availability and data adequacy before conducting aquifer mapping 4-6 1.6 Data gap analysis and data generation 6 1.6.1 Data gap analysis 6 1.6.2 Recommendation on data generation 6 1.7 Rainfall distribution 7 1.8 Physiography 7-8 1.9 Geomorphology 8 1.10 Land use 9-10 1.11Soil 11 1.12 Drainage 11-12 1.13 Agriculture 13-14 1.14 Irrigation 14 1.15 Irrigation projects: Major, Medium and Minor 15-16 1.16 Ponds, tanks and other water conservation structures 16 1.17 Cropping pattern 16-17 1.18 Prevailing water conservation/recharge practices 17 1.19 General geology 18-19 1.20 Sub surface geology 19-20 2. -

Shayesta Khan: 1.In the 17Th Century,Shayesta Khan Appointed As the Local Governor of Bengal

Class-4 BANGLADESH AND GLOBAL STUDIES ( Chapter 14- Our History ) Topic- 2“ The Middle Age” Lecture - 3 Day-3 Date-27/9/20 *** 1st read the main book properly. Middle Ages:The Middle Age or the Medieval period was a period of European history between the fall of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Renaissance. Discuss about three kings of the Middle age: Shamsuddin Ilias Shah: 1.He came to power in the 14th century. 2.His main achievement was to keep Bengal independent from the sultans of Delhi. 3.Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah opened up Shahi dynasty. Isa Khan: 1.Isa Khan was the leader of the landowners in Bengal, called the Baro Bhuiyan. 2.He was the landlord of Sonargaon. 3.In the 16th century, he fought for independence of Bengal against Mughal emperor Akhbar. Shayesta Khan: 1.In the 17th century,Shayesta Khan appointed as the local governor of Bengal. 2.At his time rice was sold cheap.One could get one mound of rice for eight taka only. 3.He drove away the pirates from his region. The social life in the Middle age: 1.At that time Bengal was known for the harmony between Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims. 2.It was also known for its Bengali language and literature. 3.Clothes and diets of Middle age wren the same as Ancient age. The economic life in the Middle age: 1.Their economy was based on agriculture. 2.Cotton and silk garments were also renowned as well as wood and ivory work. 3.Exports exceeded imports with Bengal trading in garments, spices and precious stones from Chattagram. -

Exotic Rivers of the World with Noble Caledonia

EXOTIC RIVERS OF THE WORLD WITH NOBLE CALEDONIA September 2015 to March 2016 Mekong – Irrawaddy – Ganges – Brahmaputra U2 Beinwww.noble-caledonia.co.uk Bridge, Amarapura +44 (0)20 7752 0000 SACRED RIVERS OF SOUTHEAST ASIA & INDIA No matter where you are in the world, exploring by river vessel is one of the most pleasurable ways of seeing the countryside and witnessing everyday life on the banks of the river you are sailing along. However in Southeast Asia and India it is particularly preferable. Whether you have been exploring riverside villages, remote communities, bustling markets or ancient sites and temples during the day, you can return each evening to the comfort of your vessel, friendly and welcoming staff, good food and a relaxing and convivial atmosphere onboard. Travelling by river alleviates much of the stress of moving around on land which, in Southeast Asia and India, can often be frustratingly slow as much of what we will see and do during our cruises can be approached from the banks of the river. Our journeys have been planned to incorporate contrasting and fascinating sites as well as relaxing interludes as we sail along the Mekong, Irrawaddy, Ganges or Brahmaputra. We are delighted to have chartered five small, unique vessels for our explorations which accommodate a maximum of just 56 guests. The atmosphere onboard all five vessels is friendly and informal and within days you will have made new friends in the open-seating restaurant, during the small-group shore excursions or whilst relaxing in the comfortable public areas onboard. You will be travelling amongst like-minded people but, for those who seek silence, there will always be the opportunity to relax in a secluded spot on the sun deck or simply relax in your well- appointed cabin. -

Arunachal Pradesh

Census of India 2011 ARUNACHAL PRADESH PART XII-B SERIES-13 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK WEST KAMENG VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ARUNACHAL PRADESH ARUNACHAL PRADESH DISTRICT WEST KAMENG KILOMETRES 5 0 5 10 15 NAFRA THEMBANG THRIZINO DIRANG BOMDILA JAMIRI TENGA VALLEY p o SINGCHUNG RUPA KALAKTANG SHERGAON KAMENGBARI- BHALUKPONG DOIMARA BALEMU BOUNDARY, INTERNATIONAL.................................... AREA (IN SQ.KM.).........................7422 ,, STATE...................................................... NUMBER OF CIRCLE....................13 ,, DISTRICT................................................. NUMBER OF TOWNS....................2 ,, CIRCLE.................................................... NUMBER OF CENSUS TOWN.......1 HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT/CIRCLE........................ / NUMBER OF VILLAGES.................286 VILLAGES HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION TENGA VALLEY WITH NAME.................................................................. URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE:- V, VI............................................................................... RIVER AND STREAM.................................................... District headquarters is also Circle headquarters. CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 ARUNACHAL PRADESH SERIES-13 PART XII - B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK WEST KAMENG VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations Arunachal Pradesh MOTIF National Research Centre on Yak (ICAR), Dirang: West Kameng District The National Research Center -

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

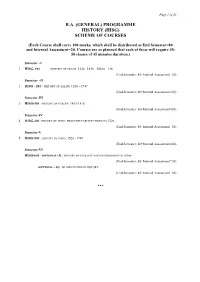

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Geological Society of America Bulletin

Downloaded from gsabulletin.gsapubs.org on July 5, 2010 Geological Society of America Bulletin Geologic correlation of the Himalayan orogen and Indian craton: Part 2. Structural geology, geochronology, and tectonic evolution of the Eastern Himalaya An Yin, C.S. Dubey, T.K. Kelty, A.A.G. Webb, T.M. Harrison, C.Y. Chou and Julien Célérier Geological Society of America Bulletin 2010;122;360-395 doi: 10.1130/B26461.1 Email alerting services click www.gsapubs.org/cgi/alerts to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Subscribe click www.gsapubs.org/subscriptions/ to subscribe to Geological Society of America Bulletin Permission request click http://www.geosociety.org/pubs/copyrt.htm#gsa to contact GSA Copyright not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in subsequent works and to make unlimited copies of items in GSA's journals for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. This file may not be posted to any Web site, but authors may post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization's Web site providing the posting includes a reference to the article's full citation. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. -

The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, Pp 232

Book Discussion Dilip K Chakrabarti: The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, pp 232 Understanding Indian Borderlands Dilip K Chakrabarti he Indian subcontinent shares borders with Iran, Afghanistan, the plateau of Tibet Tand Myanmar. The sub-continent’s influence extends beyond these borders, creating distinct ‘borderlands’ which are basically geographical, political, economic and religious interaction zones. It is these ‘borderlands’ which historically constitute the subcontinent’s ‘area of influence’ and underlines its civilizational role in the Asian landmass. A clear understanding of this civilizational role may be useful in strengthening India’s perception of her own geo-strategic position. Iran One may begin with Iran at the western limit of these borderland. There are two main mountain ranges in Iran : the Zagros which separates Iran from Iraq and has to its south the plain of Khuzestan giving access to south Iraq ; and the Elburz which separates the inland Iran from the Caspian belt, Turkmenistan and (to a limited extent , Azerbaijan). The Caspian shores form a well-wooded verdant belt which poses a strong contrast to the dry Iranian plateau. There are two deserts inside the Iranian plateau -- dasht-i-lut and dasht-i-kevir, which do not encourage human habitation. The population concentration of Iran is along the margins of the mountain belt and also in Khuzestan. The following facts are noteworthy. The eastern rim of Iran carries an imprint of the subcontinent. There is a ready access to Iranian Baluchistan through the Kej valley in Pakistani Baluchistan. At its eastern edge this valley leads both to lower Sindh and Kalat. -

Magazine-2-3.Qxd (Page 2)

SUNDAY, AUGUST 30, 2015 (PAGE-3) SACRED SPACE BOOK REVIEW Upanishads Rediscovering Hinduism in the Himalayas Surinder Koul sacerdotal rites. Description about several obliterated sculptures of Source of Spirituality Albeit, the writer is professionally medical doctor, who often trav- images of Hindu Goddess and Gods , carved pillars, floral designs els to Arunachal Pradesh, the remotest part of the country and other on plinth slabs, full lotus carved on circular stone slab in Malinithan R C Kotwal Rajasthan and M.P. of present day India. places, out of her inquisitiveness and yearning to study cultural and temple premises are mentioned in minute details . Book also car- The exact numbers of the Upanishads are not clearly architectural sites in the country, yet she has produced the book as ries out various performances of worshipping that was prevalent in Upanishads means the inner or mystic teaching. The term known. Scholars differ on the total number of Upanishads as an intellectual fallow for interested people to undertake further deep main land India among the Hindus and had been practiced by the research about cultural heritage, sociological and environmental people in Arunachal Pradesh also from ages. It has identified tem- "Upanishad" is derived from Upa(Near) , ni ( down) and shad well as what constitutes an Upanishad. Some of the Upan- (to sit) i.e sitting down near. Groups of pupils sit near the aspects of earlier called NEFA now lately rechristened as Arunachal ples precincts and ruins where worshipping of Shiva Linga, worship- ishads are very ancient, but some are of recent origin. Pradesh. This region Arunachal Pradesh, had remained neglected ping of Durga as Malini still exist and on auspicious occasion devo- teacher to learn from him the secret doctrine. -

Statistical Hand Book

STATISTICAL HAND BOOK OF WEST KAMENG DISTRICT Arunachal Pradesh 1992 District Statistical Office, Bomdila f o r e w o r d The Distxict Statistical Hand-Book of West Kameng s 1992 has been prepared as per the standard formats of the Directorate of Economics Statistics, Government of Aranachal Pradesh, and it endeavours to portray a comprehensive picture of the achievements of various Government Departments in West Kameng. The publication is the result of collection of facts and figures and their analytical coinpilation by the staff of Statistical Cell under the guidance of the District Statistical Officer, Bomdila, I hope/ th is Hand-BooV. w i l l be of con sid era ble value and assistance to the District officials and others concerned in plabnrin^ futiire development of the f area. ( D.R. Nafri )IAS Deputy Commissioner, Bomdila^ West Kameng District, March/1993. Bomdila, NIEPA DC D07458 i m m ^ DOCUMENTATION m m >atjcn:;! J jsrjtute of Kducatioaal P'Irtan . .4. ' ad Adm inistration. iV-B, :ri Aurobindo Matf* . i . tbi-110016 DOC^ Na ^ •■ ...... C^ate ...... INPRODUCriON Statistics are numerical statements of fact capable of analysis and interpretation. The S t a t is t ic a l Hanid-Book of West Kameng s 1992 presents a crystal clear picture of various developmen tal activities and socio-economic aspects of the dist rict* The booklet also inco-rporates some special tables on Vital Statistics, Govt, Eimployees in West Kameng District and sector-wise distribution of Net State Dome stic Product of Arunachal Pradesh, The compilation of this issue has been done in conformity with the State Level publication, I take this opportunity to extend my thanks and gratitude to all the district heads of departments for their co-operation in bringing out this publication. -

Trade and Transport Connectivity in the Bay of Bengal Region Bridging the East Trade and Transport Connectivity in the Bay of Bengal Region

Bridging the East Trade and Transport Connectivity in the Bay of Bengal Region Bridging the East Trade and Transport Connectivity in the Bay of Bengal Region Published By D-217, Bhaskar Marg, Bani Park, Jaipur 302016, India Tel: +91.141.2282821, Fax: +91.141.2282485 Email: [email protected], Web site: www.cuts-international.org With the support of In partnership with Unnayan Shamannay © CUTS International, 2019 Citation: CUTS (2019), Bridging the East Trade and Transport Connectivity in the Bay of Bengal Region Printed in India by M S Printer, Jaipur ISBN 978-81-8257-275-1 This document is an output of a project entitled ‘Creating an Enabling and Inclusive Policy and Political Economy Discourse for Trade, Transport and Transit Facilitation in and among Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal and Myanmar: Facilitating implementation and stakeholder buy-in in the BBIN group of countries and Myanmar sub-region’. This publication is made possible with the support of the Department for International Development, UK. The views and opinions expressed in this publication is that of CUTS International and partners and not those of the Department for International Development, UK. #1903, Suggested Contribution M250/US$25 Contents Abbreviations 7 Contributors 9 Acknowledgements 13 Preface 15 Executive Summary 17 1. Introduction 23 Trade Connectivity: Existing and Proposed Initiatives 23 Salient Features of BBIN MVA 25 Significance of BBIN MVA 27 Standardisation and Formalisation of Trade 27 Economic and Developmental Significance 27 Integration with Larger Developmental Agenda 28 Strategic and Diplomatic Significance 29 2. Research Methodology and Implementation Plan 30 Define the Target Population 30 Connections among the Different Types of Stakeholders 31 Choice of Sampling Technique 32 Determination of Sample Size: Corridors, Products and Respondents 32 Data Collection 34 3. -

Kīrtimukha in the Art of the Kapili-Jamuna Valley of Assam: An

Kīrtimukha in the Art of the Kapili-Jamuna Valley of Assam: An Artistic Survey RESEARCH PAPER MRIGAKHEE SAIKIA PAROMITA DAS *Author affiliations can be found in the back matter of this article ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Mrigakhee Saikia The figure of thek īrtimukha or ‘glory- face’ is an artistic motif that appears on early Gauhati University, IN Indian art and architecture, initially as a sacred symbol and then more commonly as [email protected] a decorative element. In Assam, the motif of kīrtimukha is seen crowning the stele of the stray icons of the early medieval period. The motif also appeared in the structural components of the ancient and early medieval temples of Assam. The Kapili-Jamuna valley, situated in the districts of Nagaon, Marigaon and Hojai in central Assam houses TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Saikia, M and Das, P. 2021. innumerable rich archaeological remains, especially temple ruins and sculptures, Kīrtimukha in the Art of the both stone and terracotta. Many such architectural components are adorned by the Kapili-Jamuna Valley of kīrtimukha figures, usually carved in low relief. It is proposed to discuss the iconographic Assam: An Artistic Survey. features of the kīrtimukha motif in the art of the Kapili-Jamuna valley of Assam and Ancient Asia, 12: 2, pp. 1–15. also examine whether the iconographic depictions of the kīrtimukha as prescribed in DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ canonical texts, such as the Śilpaśāstras are reflected in the art of the valley. Pan Asian aa.211 linkages of the kīrtimukha motif will also be examined. INTRODUCTION Saikia and Das 2 Ancient Asia Quite inextricably, art in India, in its early historical period, mostly catered to the religious need of DOI: 10.5334/aa.211 the people.