Heritage of Architecture of Assam – Need for Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class-6 New 2020.CDR

Foreword I am greatly pleased to introduce the inaugural issue of “rediscovering Assam- An Endeavour of DPS Guwahati” . The need for familiarizing the students with the rich historical background, unique geographical features and varied flora and fauna of Assam had long been felt both by the teaching fraternity as well as the parent community. The text has been prepared by the teachers of Delhi Public School Guwahati with the sole aim of fulfilling this need. The book which has three parts will cater to the learning requirement of the students of classes VI, VII, VIII. I am grateful towards the teachers who have put in their best efforts to develop the contents of the text and I do hope that the students will indeed rediscover Assam in all its glory. With best wishes, Chandralekha Rawat Principal Delhi Public School Guwahati @2015 ; Delhi Public School Guwahati : “all rights reserved” Index Class - VI Sl No. Subject Page No. 1 Environmental Science 7-13 2 Geography 14-22 3 History 23-29 Class - VII Sl No. Subject Page No. 1 Environmental Science 33-39 2 Geography 40-46 3 History 47-62 Class - VIII Sl No. Subject Page No. 1 Environmental Science 65-71 2 Geography 72-82 3 History 83-96 CLASS-VI Assam, the north-eastern sentinel of the frontiers of India, is a state richly endowed with places of tourist attractions (Fig.1.1). Assam is surrounded by six of the other Seven Sister States: Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura, and Meghalaya. Assam has the second largest area after Arunachal Pradesh. -

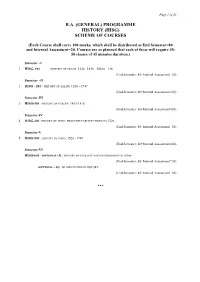

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, Pp 232

Book Discussion Dilip K Chakrabarti: The Borderlands and Borders of the Indian Subcontinent, New Delhi: Aryan Books International, 2018, pp 232 Understanding Indian Borderlands Dilip K Chakrabarti he Indian subcontinent shares borders with Iran, Afghanistan, the plateau of Tibet Tand Myanmar. The sub-continent’s influence extends beyond these borders, creating distinct ‘borderlands’ which are basically geographical, political, economic and religious interaction zones. It is these ‘borderlands’ which historically constitute the subcontinent’s ‘area of influence’ and underlines its civilizational role in the Asian landmass. A clear understanding of this civilizational role may be useful in strengthening India’s perception of her own geo-strategic position. Iran One may begin with Iran at the western limit of these borderland. There are two main mountain ranges in Iran : the Zagros which separates Iran from Iraq and has to its south the plain of Khuzestan giving access to south Iraq ; and the Elburz which separates the inland Iran from the Caspian belt, Turkmenistan and (to a limited extent , Azerbaijan). The Caspian shores form a well-wooded verdant belt which poses a strong contrast to the dry Iranian plateau. There are two deserts inside the Iranian plateau -- dasht-i-lut and dasht-i-kevir, which do not encourage human habitation. The population concentration of Iran is along the margins of the mountain belt and also in Khuzestan. The following facts are noteworthy. The eastern rim of Iran carries an imprint of the subcontinent. There is a ready access to Iranian Baluchistan through the Kej valley in Pakistani Baluchistan. At its eastern edge this valley leads both to lower Sindh and Kalat. -

Chiipter I Introduction

. ---- -·--··· -··-·- ------ -·-- ·----. -- ---~--- -~----------------~~---- ~-----~--~-----~-·------------· CHIIPTER I INTRODUCTION A Brief Survey of Land and People of the Area Under Study T~e present district of Kamrup, created in 1983, is. bounded by Bhutan on the north~ districts of Pragjyoti~pur and Nagaon on the east, Goalpara and Nalbari on the west and the s t LJ t e of 11 e 9 hal a y a u n t 1'1 e s u u t h . l L tl d s d n d rea of 4695.7 sq.kms., and a population of 11'106861 . Be"fore 1983, Kamrup was comprised of four present districts viz., Kamrup, Nalbari, Barpeta and ~ragjyotispur with a total 2 area of 'l863 sq.kms. and a population of 28,54,183. The density of population was 289 per sq.km. It was then boun- ded by Bhutan on the north, districts of Darrang and Nagaon on the east, district of Goalpara on the west and the state of neghalaya on the south. Lying between 26°52'40n and 92°52'2" north latitude and '10°44'30" and '12°12'20~ east longitude, the great river Brahmaputra divides it into two halves viz., South Kamrup and North Kamrup. The northern 1 statistical Handbook of Assam, Government of Assam, 1987, p.6. 2 Census, 1971·· 2 . 3 portion is about twice the area of the southern port1on . All of the rivers and streams which intersect the district arise in the hills and mountains and flow into the Brahmaputra. The principal northern tributaries are the Manas, the Barnadi and the ?agladia which rise in the Himalaya mountains- These rivers have a tendency to change their course and wander away from the former channels because of the direct push from the Himalayas. -

Magazine-2-3.Qxd (Page 2)

SUNDAY, AUGUST 30, 2015 (PAGE-3) SACRED SPACE BOOK REVIEW Upanishads Rediscovering Hinduism in the Himalayas Surinder Koul sacerdotal rites. Description about several obliterated sculptures of Source of Spirituality Albeit, the writer is professionally medical doctor, who often trav- images of Hindu Goddess and Gods , carved pillars, floral designs els to Arunachal Pradesh, the remotest part of the country and other on plinth slabs, full lotus carved on circular stone slab in Malinithan R C Kotwal Rajasthan and M.P. of present day India. places, out of her inquisitiveness and yearning to study cultural and temple premises are mentioned in minute details . Book also car- The exact numbers of the Upanishads are not clearly architectural sites in the country, yet she has produced the book as ries out various performances of worshipping that was prevalent in Upanishads means the inner or mystic teaching. The term known. Scholars differ on the total number of Upanishads as an intellectual fallow for interested people to undertake further deep main land India among the Hindus and had been practiced by the research about cultural heritage, sociological and environmental people in Arunachal Pradesh also from ages. It has identified tem- "Upanishad" is derived from Upa(Near) , ni ( down) and shad well as what constitutes an Upanishad. Some of the Upan- (to sit) i.e sitting down near. Groups of pupils sit near the aspects of earlier called NEFA now lately rechristened as Arunachal ples precincts and ruins where worshipping of Shiva Linga, worship- ishads are very ancient, but some are of recent origin. Pradesh. This region Arunachal Pradesh, had remained neglected ping of Durga as Malini still exist and on auspicious occasion devo- teacher to learn from him the secret doctrine. -

Hindutva Paper

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Power of Persuasion Citation for published version: Longkumer, A 2017, 'The Power of Persuasion: Hindutva, Christianity, and the discourse of religion and culture in Northeast India', Religion, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 203-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2016.1256845 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/0048721X.2016.1256845 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Religion Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Religion on 7/12/2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/0048721X.2016.1256845 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 The Power of Persuasion: Hindutva, Christianity, and the discourse of religion and culture in Northeast India.1 Abstract: The paper will examine the intersection between Sangh Parivar activities, Christianity, and indigenous religions in relation to the state of Nagaland. I will argue that the discourse of ‘religion and culture’ is used strategically by Sangh Parivar activists to assimilate disparate tribal groups and to envision a Hindu nation. -

Lesser Known Capitals of Bengal Before Calcutta: Geo-Historical Aspects of ‘Tanda’

International Bilingual Journal of Culture, Anthropology and Linguistics (IBJCAL), eISSN: 2582-4716 https://www.indianadibasi.com/journal/index.php/ibjcal/issue/view/3 VOLUME-2, ISSUE-1, ibjcal2020M01, pp. 1-10 1 Lesser Known Capitals of Bengal Before Calcutta: Geo-Historical Aspects of ‘Tanda’ Samir Ganguli Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Tanda was the capital of Sultan Sulaiman Khan Karrani, ruler of Received : 26.07.2020 Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, who shifted his capital from Gaur to Received (revised form): Tanda in 1565. It was the capital of Bengal Sultanate till 1576, till 01.09.2020 Sulaiman’s son Sultan Daud Khan, declared independence from the Accepted : 10.09.2020 Mughals which cost him his kingdom and life in 1576. Tanda Paper_Id : ibjcal2020M01 continued as the capital of Bengal Subah of the Mughals till Raja Man Singh shifted the capital to Rajmahal in 1595, except for a short period when the capital was shifted by Munim Khan to Gaur. Keywords: Tanda was located at the juncture of Padma and Bhagirathi, about Tanda 15 miles from Gaur. As happened with many cities of Bengal Bengal Sultanate located on the banks of rivers, Tanda also suffered the same fate. Sulaiman Karrani Tanda does not exist today. It is said that in about 1826, the city Daoud Karrani was destroyed by floods and disappeared into the river. Capitals of Bengal Lesser known capitals 1.0 Introduction Bengal has a rich history over hundreds of years and there have been many capitals in this part of the country over this period. -

Aspects of Ancient Indian Art and Architecture

ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE M.A. History Semester - I MAHIS - 101 SHRI VENKATESHWARA UNIVERSITY UTTAR PRADESH-244236 BOARD OF STUDIES Prof (Dr.) P.K.Bharti Vice Chancellor Dr. Rajesh Singh Director Directorate of Distance Education SUBJECT EXPERT Dr. S.K.Bhogal, Professor Dr. Yogeshwar Prasad Sharma, Professor Dr. Uma Mishra, Asst. Professor COURSE CO-ORDINATOR Mr. Shakeel Kausar Dy. Registrar Author: Dr. Vedbrat Tiwari, Assistant Professor, Department of History, College of Vocational Studies, University of Delhi Copyright © Author, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 -

•Prag Means Former Or Eastern and Jyotisa a Star

II ' I I CHAPTER 1 I HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The history of Assam is, in great extent the history of the Brahmaputra Valley. Historical materials on which a reliable framework of her early history i.e. pre-Ahom history can be reconstructed, are very megre. For this period. we have to depend mainly on some megalithic and neolithic findings, a few local epigraphs apart from some archeological remains and scattered literary documents - historical and otherwise. In the ancient times Assam was known as Pragjyotisha and Karnarupa. Of these two names Pngjyotisha was more ancient. lt was by this name that the country was known in the Ram!lyana and the Mahabharata and also in some of the principal PUranas. The Kalika PUrana, a work of the lOth century A.D. says, "Formerly Brahma staying here created the stars, so the city 1 is called Pragjyotisapura a city equal to the city of lndra•. This etymological explanation given by the K&lika PUrana has been followed by the historians. Gait writes, •prag means former or eastern and Jyotisa a star, astrology, shining. Pragjyotis~pura may be tekn to mean the city of Eastern Astrology". 2 Follo'tling him, K.L. Barua points out that "to the immediate east of the town of --------- -- --- -- 2 ,,,, Gu"'ahati there is a temple on the crest of a hill known as Chitrachal and this temple is dedicated to the Navagrahas or the nine planets. It is probable that this temple is the origin of the name pragjyoti?hp~ra.~ hbout the name Kamarupa, the Kalika purana says that it was r.;arak of Hithila who after becoming king was placed in. -

History of Assam Upto the 16Th Century AD

GHT S5 01(M/P) Exam Code : HTP 5A History of Assam upto the 16th Century AD SEMESTER V HISTORY BLOCK 1 KRISHNA KANTA HANDIQUI STATE OPEN UNIVERSITY History of Assam up to the 16th century A.D.(Block 1) 1 Subject Experts 1. Dr. Sunil Pravan Baruah, Retd. Principal, B.Barooah College, Guwahati 2. Dr. Gajendra Adhikari, Principal, D.K.Girls’ College, Mirza 3. Dr. Maushumi Dutta Pathak, HOD, History, Arya Vidyapeeth College, Guwahati Course Coordinator : Dr. Priti Salila Rajkhowa, Asst. Prof. (KKHSOU) SLM Preparation Team UNITS CONTRIBUTORS 1,2,3,4 Muktar Rahman Saikia, St. John College Dimapur, Nagaland 5 Dr. Mridutpal Goswami, Dudhnoi College 6& 7 Dr. Mamoni Sarma, LCB College Editorial Team Content (English Version) : Prof. Paromita Das, Deptt. of History, GU Language (English Version) : Rabin Goswami, Retd. Professor, Deptt. of English, Cotton College Structure, Format & Graphics : Dr. Priti Salila Rajkhowa, KKHSOU June, 2019 © Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University This Self Learning Material (SLM) of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State University is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License (International) : http.//creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0 Printed and published by Registrar on behalf of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University. Head Office : Patgaon, Rani Gate, Guwahati-781017; Web : www.kkhsou.in City Office: Housefed Complex, Dispur, Guwahati-781006 The University acknowledges with thanks the financial support provided by the Distance Education Bureau, UGC -

History of Śākta Pīthas in Assam (Upto 18Th Century)

HISTORY OF ŚĀKTA PĪTHAS IN ASSAM (UPTO 18TH CENTURY) An Abstract Submitted to Assam University, Silchar, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in History Submitted by Rumi Patar Ph. D. Registration No: Ph. D/1482/2011 Date - 19.04.2011 Supervisor Dr. Projit Kumar Palit Professor Department of History DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY JADUNATH SARKAR SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE ASSAM UNIVERSITY, SILCHAR 2015 History of Śākta Pîthas in Assam (upto 18th Century) Śȃkta pîthas are the seat or abode of the Goddess in Her different manifestations at different places. There is a legend related to the origin of the Śākta pîthas in Kȃlikȃ Purȃna, Yoginî Tantra, in the Epic Mahȃbhȃrata and in many religious literatures. Assam has been considered as the suitable place of worshipping the Goddess Śakti in various forms since time immemorial. Nobody can ascertain the exact date of the prevalence of Śakti worship in Assam. But some scholars ascertain that Śakti worship started in Assam from the pre-historic time. However many scholars are of the opinion that Naraka was the first Śȃkta worshipper in Assam who was the staunch follower of the then residing deity Kȃmȃkhyȃ. The most striking characteristic of ancient Assam (Prȃgjyotisha-Kȃmarūpa) was the Śakti cult which was the dominant and influential cult of Assam in the early period. It has been worshipped in different forms at different places in different times. Various literary evidence, inscriptions and sculptures of Assam are regarded as the most reliable sources which supply us authentic information about the prevalence of Śakti cult and its various forms even down to the Ahom rule upto 18th century CE. -

The Legacy of Assam Sanjeewani Widyarathne1 Abstract Northeastern India Is One of the Most Ethnically Diverse Regions of the World

The legacy of Assam Sanjeewani Widyarathne1 Abstract Northeastern India is one of the most ethnically diverse regions of the world. The region shares its border with Bhutan, China, Myanmar and Bangladesh. Assam is one of the eight states in the Northeast Region of India and serves as the gateway to the rest of the seven sister and one brother states (Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Tripura, Mizoram and Sikkim). Assam comprises three main geographical areas: The Brahmaputra Valley, the Barak and the Karbi Plateau. The historical account of Assam begins with the establishment of Pushyavarman's Varman dynasty in the 4th century in the Kamarupa Kingdom which marks the beginning of Ancient Assam. The Kingdom reached its traditional extent from the Karatoya in the west to Sadiya in the east. This and the two succeeding dynasties drew their lineage from the mythical Narakasura. The Kingdom reached its zenith under Bhaskara Varman in the 7th century. Bhaskaravarman died without leaving behind an issue and the control of the country. The fall of the kingdoms and rise of individual kingdoms in the 12th century marked the end of the Kamarupa Kingdom and the period of Ancient Assam. In the middle of the 13th century, Sandhya, a king of Kamarupa moved his capital to Kamatapur. The last of the Kamata kings, the Khens, were removed by Alauddin Hussain Shah in 1498. But Hussein Shah and subsequent rulers could not consolidate their rule in the Kamata Kingdom, mainly due to the revolt by the Bhuyan chieftains, a relic of the Kamarupa administration and other local groups.