Kings and Cults in the Land of Kamakhya up To1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

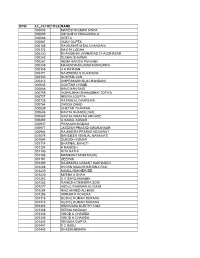

Dpid Lf Cltid Title Name 000006 Mahesh Kumar Sinha 000009

DPID LF_CLTID TITLE NAME 000006 MAHESH KUMAR SINHA 000009 ASHA M CHHANGAWALA 000066 GEETA 000087 VIJAY GUPTA 000105 RAJKUMAR M BALCHANDANI 000174 KAVITA LODHA 000230 BHANUBHAI JAMNADAS CHALISHAZAR 000240 SUMAN SHARMA 000251 HEMA HARISH PUNJABI 000349 MAHENDRAKUMAR KANKERIYA 000355 A H PATHAN 000371 RAJENDRA S SUKHADIA 000380 SUSHMA JAIN 000413 OMPRAKASH BULCHANDANI 000645 GOUTAM CHAND 000668 KANCHAN BAID 000709 GOPALBHAI SHAMJIBHAI TOPIYA 000727 NEERAJ GUPTA 000735 RATANLAL DHAREWA 000764 ZARQA ZAHID 000839 CHETAN THAKKAR 000846 KAVITA KHANDELWAL 000889 SAVITA VINAYAK ARGADE 000892 U KAMAL KUMAR 000937 PRAKASH KODAM 000977 JAGDISH PRASAD SWARANKAR 000984 RAJENDRA PRASAD KEDAWAT 001078 BANSIBEN VENILAL NANAVATI 001084 SUBODH KUMAR 001114 BHATMAL BAHETI 001124 K RAMESH 001145 RITA RATHI 001186 MANIKANT M MATHURE 001191 DEEPAK 001209 RAJENDRA VASANT SAKHADEO 001228 KVGSN MALLIKHARJUNA RAO 001239 KAMAL MUKHERJEE 001240 MEENA K SHAH 001253 D V SAROJINAMMA 001263 RAMESH CHANDRA SONI 001277 ABDUL RAHIMAN ALI BAIG 001284 NIAZ AHMED ALI BAIG 001286 VIKRAM R VOHERA 001316 SUSHIL KUMAR SURANA 001318 SUSHIL KUMAR SURANA 001323 SRINIVASA MURTHY UMA 001328 SEEMA MADAAN 001343 VINOD A CHAWDA 001345 VINOD A CHAWDA 001436 RENUKA GUPTA 001441 K C BABU 001443 SHASHI MISHRA 001458 ASHOK KUMAR GANGWAL 001485 DINESH KUMAR AGARWAL 001491 DEBABRATA SENGUPTA A00016 ABHAY JAIN A00029 AJAY V BHATT A00032 AJIT V MADYE A00038 ALOK KUMAR MAHENSARIA A00046 AMITA TULSYAN A00056 ANANTRAJ ANILKUMAR PATWA A00063 ANIL KUMAR A00067 ANIL KUMAR MAHENSARIA A00073 ANITA MARIA -

Lohit District GAZETTEER of INDIA ARUNACHAL PRADESH LOHIT DISTRICT ARUNACHAL PRADESH DISTRICT GAZETTEERS

Ciazetteer of India ARUNACHAL PRADESH Lohit District GAZETTEER OF INDIA ARUNACHAL PRADESH LOHIT DISTRICT ARUNACHAL PRADESH DISTRICT GAZETTEERS LOHIT DISTRICT By S. DUTTA CHOUDHURY Editor GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1978 Published by Shri M.P. Hazarika Director of Information and Public Relations Government of Amnachal Pradesh, Shillong Printed by Shri K.K. Ray at Navana Printing Works Private Limited 47 Ganesh Chunder Avenue Calcutta 700 013 ' Government of Arunachal Pradesh FirstEdition: 19781 First Reprint Edition: 2008 ISBN- 978-81-906587-0-6 Price:.Rs. 225/- Reprinted by M/s Himalayan Publishers Legi Shopping Corqplex, BankTinali,Itanagar-791 111. FOREWORD I have much pleasure in introducing the Lohit Distri<^ Gazetteer, the first of a series of District Gazetteers proposed to be brought out by the Government of Arunachal Pradesh. A'Gazetteer is a repository of care fully collected and systematically collated information on a wide range of subjects pertaining to a particular area. These information are of con siderable importance and interest. Since independence, Arunachal Pra desh has been making steady progress in various spheres. This north-east frontier comer of the country has, during these years, witnessed tremen dous changes in social, economic, political and cultural spheres. These changes are reflected in die Gazetteers. 1 hope that as a reflex of these changes, the Lohit District Gazetteer would prove to be quite useful not only to the administrators but also to researdi schplars and all those who are keen to know in detail about one of the districts of Arunachal Pradesh. Raj Niwas K. A. A. Raja Itanagar-791 111 Lieutenant Governor, Arunachal Pradesh October 5, i m Vili I should like to take this opportunity of expressing my deep sense of gratitude to Shri K; A. -

LIST of ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED for the POST of GD. IV of AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT of DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR

LIST OF ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR THE POST OF GD. IV OF AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT OF DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR Date of form Sl Post Registration No Candidate Name Father's Name Present Address Mobile No Date of Birth Submission 1 Grade IV 101321 RATUL BORAH NAREN BORAH VILL:-BORPATHAR NO-1,NARAYANPUR,GOSAIBARI,LAKHIMPUR,Assam,787033 6000682491 30-09-1978 18-11-2020 2 Grade IV 101739 YASHMINA HUSSAIN MUZIBUL HUSSAIN WARD NO-14, TOWN BANTOW,NORTH LAKHIMPUR,KHELMATI,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 6002014868 08-07-1997 01-12-2020 3 Grade IV 102050 RAHUL LAMA BIKASH LAMA 191,VILL NO 2 DOLABARI,KALIABHOMORA,SONITPUR,ASSAM,784001 9678122171 01-10-1999 26-11-2020 4 Grade IV 102187 NIRUPAM NATH NIDHU BHUSAN NATH 98,MONTALI,MAHISHASAN,KARIMGANJ,ASSAM,788781 9854532604 03-01-2000 29-11-2020 5 Grade IV 102253 LAKHYA JYOTI HAZARIKA JATIN HAZARIKA NH-15,BRAHMAJAN,BRAHMAJAN,BISWANATH,ASSAM,784172 8638045134 26-10-1991 06-12-2020 6 Grade IV 102458 NABAJIT SAIKIA LATE CENIRAM SAIKIA PANIGAON,PANIGAON,PANIGAON,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787052 9127451770 31-12-1994 07-12-2020 7 Grade IV 102516 BABY MISSONG TANKESWAR MISSONG KAITONG,KAITONG ,KAITONG,DHEMAJI,ASSAM,787058 6001247428 04-10-2001 05-12-2020 8 Grade IV 103091 MADHYA MONI SAIKIA BOLURAM SAIKIA Near Gosaipukhuri Namghor,Gosaipukhuri,Adi alengi,Lakhimpur,Assam,787054 8011440485 01-01-1987 07-12-2020 9 Grade IV 103220 JAHAN IDRISH AHMED MUKSHED ALI HAZARIKA K B ROAD,KHUTAKATIA,JAPISAJIA,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 7002409259 01-01-1988 01-12-2020 10 Grade IV 103270 NIHARIKA KALITA ARABINDA KALITA 006,GUWAHATI,KAHILIPARA,KAMRUP -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Full Text: DOI

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Special Conference Issue (Vol. 12, No. 5, 2020. 1-11) from 1st Rupkatha International Open Conference on Recent Advances in Interdisciplinary Humanities (rioc.rupkatha.com) Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n5/rioc1s17n3.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n5.rioc1s17n3 Identity, Indigeneity and Excluded Region: In the Quest for an Intellectual History of Modern Assam Suranjana Barua1 & L. David Lal2 1Assistant Professor in Linguistics, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Information Technology Guwahati, Assam, India. Email: [email protected] 2Assistant Professor in Political Science, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Information Technology Guwahati, Assam, India. Email: [email protected] Abstract If Indian intellectual history focussed on the nature of the colonial and post-colonial state, its interaction with everyday politics, its emerging society and operation of its economy, then how much did/ does North- East appear in this process of doing intellectual history? North-East history in general and its intellectual history in particular is an unpeopled place. In Indian social science literature, North-East history for the last seventy years has mostly revolved around separatist movements, insurgencies, borderland issue and trans- national migration. However, it seldom focussed on the intellectuals who have articulated the voice of this place and constructed an intellectual history of this region. This paper attempts to explore the intellectual history of Assam through understanding the life history of three key socio-political figures – Gopinath Bordoloi, Bishnu Prasad Rabha and Chandraprabha Saikiani. -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

Chiipter I Introduction

. ---- -·--··· -··-·- ------ -·-- ·----. -- ---~--- -~----------------~~---- ~-----~--~-----~-·------------· CHIIPTER I INTRODUCTION A Brief Survey of Land and People of the Area Under Study T~e present district of Kamrup, created in 1983, is. bounded by Bhutan on the north~ districts of Pragjyoti~pur and Nagaon on the east, Goalpara and Nalbari on the west and the s t LJ t e of 11 e 9 hal a y a u n t 1'1 e s u u t h . l L tl d s d n d rea of 4695.7 sq.kms., and a population of 11'106861 . Be"fore 1983, Kamrup was comprised of four present districts viz., Kamrup, Nalbari, Barpeta and ~ragjyotispur with a total 2 area of 'l863 sq.kms. and a population of 28,54,183. The density of population was 289 per sq.km. It was then boun- ded by Bhutan on the north, districts of Darrang and Nagaon on the east, district of Goalpara on the west and the state of neghalaya on the south. Lying between 26°52'40n and 92°52'2" north latitude and '10°44'30" and '12°12'20~ east longitude, the great river Brahmaputra divides it into two halves viz., South Kamrup and North Kamrup. The northern 1 statistical Handbook of Assam, Government of Assam, 1987, p.6. 2 Census, 1971·· 2 . 3 portion is about twice the area of the southern port1on . All of the rivers and streams which intersect the district arise in the hills and mountains and flow into the Brahmaputra. The principal northern tributaries are the Manas, the Barnadi and the ?agladia which rise in the Himalaya mountains- These rivers have a tendency to change their course and wander away from the former channels because of the direct push from the Himalayas. -

Positioning of Assam As a Culturally Rich Destination: Potentialities and Prospects

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue 3 Ser. IV || Mar, 2020 || PP 34-37 Positioning Of Assam as a Culturally Rich Destination: Potentialities and Prospects Deepjoonalee Bhuyan ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 22-03-2020 Date of Acceptance: 08-04-2020 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. INTRODUCTION Cultural tourism has a special place in India because of its past civilisation. Among the various motivating factors governing travel in India, cultural tourism is undoubtedly the most important. For any foreigner, a visit to India must have a profound cultural impact and in its broader sense, tourism in India involves quite a large content of cultural content. It also plays a major role in increasing national as well as international good will and understanding. Thousands of archaeological and historical movements scattered throughout the country provide opportunites to learn about the ancient history and culture. India has been abundantly rich in its cultural heritage. Indian arts and crafts, music and dance, fairs and festivals, agriculture and forestry, astronomy and astrology, trade and transport, recreation and communication, monumental heritage, fauna and flora in wildlife and religion play a vital role in this type of tourism. Thus, it can be very well said that there remains a lot of potential for the progress of cultural tourism in India. Culturally, North East represents the Indian ethos of „unity in diversity‟ and „diversity in unity‟. It is a mini India where diverse ethnic and cultural groups of Aryans, Dravidians, Indo-Burmese, Indo Tibetan and other races have lived together since time immemorial. -

The TAI AHOM Movement in Northeast India: a Study of All Assam TAI AHOM Student Union

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 7, Ver. 10 (July. 2018) PP 45-50 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The TAI AHOM Movement in Northeast India: A Study of All Assam TAI AHOM Student Union Bornali Hati Boruah Research Scholar Dept. of Political science Assam University, Diphu campus, India Corresponding Author: Bornali Hati Boruah Abstract: The Ahoms, one of the foremost ethnic communities in the North East India are a branch of the Tai or Shan people. The Tai Ahoms entered the Brahmaputra valley from the east in the early part of the thirteenth century and their arrival heralded a new age for the people of the region. The ethnic group Tai Ahoms of Assam has been asserting their ethnic identity more than a century old today. The Ahoms who once ruled over Assam seek to maintain their distinct identity within the larger Assamese society. The Tai Ahoms of Assam faced a lot of problem after independence in different aspects. Moreover, though once Tai Ahoms ancestors were ruling race but today they have been squarely backward .They have been recognized as one of the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category. As a measure to solve their multifold and multifaceted demands, the ethnic group Tai Ahoms has been struggling through their organizations. In present time, All Tai Ahom Student Union (ATASU) has been very much concerned about the various problems of Tai Ahoms community. While struggling for the overall development of the Tai Ahom community, rightly or wrongly the All Tai Ahom Student Union has been raising political issues and thus got involved in the politics of the state despite being a non-political organization. -

•Eak-Tet Parenfe

- ■ r " www.inagicvallel l e y . c o m ^ ^ T h l e s b I •Sd cents-. ..........- ^Twin Falls, Idahiiho/98ih year, N o7 ^3 4 4 0 --■ ■■;■ --------------------- - Sanirday,, 1Dcccmbcr 6,'20(B3 ° - - - - T G o o b m o rNING.- n .... C( WKA'I'HKR o p s n :a b s u i s p e c it i n b ) a b y aI s s a u[ l it Today: > Sgt. George Erskine. - -^^o C f^ -Scattere■red rain ByRsbMcal»I M eany-;; “ 1 1 “ ------- - i &^H|jH|b tbday'ana n d : ■ Tlmes^owsrwriter w ' ' •' -Filerm an now ffaces^escape,-aufofotH eft cliafge.s—“ -CountySheriff’y-Departn ■ — to the father’s house Fridiiy] to a ' W ~ t o n i ^I t t, , h ig h in(iuire if he luid seen th • 0 “^ 50,Iowy 335. TWIN FALALLS - A Filer man sus- '• Jackman has been charjiirged \sith Johnson saidaid. Wearing handcuffs, t managed lo get oul of Johnson said. pccted of sasexually abusing a child oone coimt of lewd and 1.lascivious ' the suspect ti PPage A2 “Tile dad said. 'Yeah,, hhe's here,"' and then fle<fleeing from police after C'conduct with a m inor an dI o ne count the car, and Ja a police search failed to ' I his arrest WtWednesday was back in oof injuiy to a cliild, He; inow also locate him; Jolm son said. faces ciiarges of escape aiand grand Police saidnid Friday they learned ’Hie suspect \s-as hidirling bi'l'.iiid J , M a g i c V a i . -

Key Official Information

Key Official Information STD Code : 0361 Name & Designation Phone & Fax Mobile E_Mail ID 1 Shri Alok Kumar, IAS 2261403 [email protected] Chief Secretary 2261120 (R ) 2260900 (Fax) 4 Shri Mukesh Ch. Sahu, IAS 2231465 (O) 9435201234 [email protected] 2362104 (R ) Set up at Chief Electoral Officer for Election Management Name & Designation Phone & Fax Mobile E_Mail ID 1 Shri Nazrul Islam, IAS 70021-15511 [email protected] Secretary & Additional CEO, Assam 2 Shri Vibekananda Phookan, 94355-91346 ACS, Secy. & Addl. CEO, Assam 3 Shri Mohan Lal Sureka, 2262268 (O) 94014-54338 ACS, Joint Secy., and Jt. CEO, Assam 4 Shri Diganta Das, ACS 99577-22253 [email protected] Dy. Secy. & Jt. CEO, Assam 5 Shri Bishnu Dutta Sarma, 94351-86111 [email protected] ACS, Dy. Secy. & Jt. CEO, Assam 6 Shri Pranjal Choudhury, 84720-85480 [email protected] ACS, Dy. Secy. 7 Pankaj Chakraborty, ACS, 94351-11396 Deputy Secretary Home Department 1 Shri Kumar Sanjay Krishna 2237273 [email protected] , IAS Addl. Chief Secretary, Home 2 Shri Kuladhar Saikia, IPS 2526601 94350-49624 [email protected] Director General of Police [email protected] 3 Shri Mukesh Agarwal, IPS 2456971 94350-48633 [email protected] ADGP (L&)) and Nodal Police Officer, Elections State Nodal Officer STD Code - 0361 Sl. Name & Designation Nodal Officer Mobile E-mail ID No. of the Officers for No. Vibekananda Phukan, Office of the ACS, Secretary, Election 9435591346 [email protected] CEO 1 Department. State Police/ Co- 9435048633 Mukesh Agarwal, IPS, ordination with 2456971 [email protected] ADGP, Assam 2 CAPF & Security 2737711 Rakesh Kumar, IAS, State Excise Commissioner of Excise, 9101283447 [email protected] Department 3 Assam Subhrojyoti bhattacharjee, Income Tax IRS,Addl. -

Unit 6: Religious Traditions of Assam

Assamese Culture: Syncretism and Assimilation Unit 6 UNIT 6: RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS OF ASSAM UNIT STRUCTURE 6.1 Learning Objectives 6.2 Introduction 6.3 Religious Traditions of Assam 6.4 Saivism in Assam Saiva centres in Assam Saiva literature of Assam 6.5 Saktism in Assam Centres of Sakti worship in Assam Sakti literature of Assam 6.6 Buddhism in Assam Buddhist centres in Assam Buddhist literature of Assam 6.7 Vaisnavism in Assam Vaisnava centres in Assam Vaisnava literature of Assam 6.8 Let Us Sum Up 6.9 Answer To Check Your Progress 6.10 Further Reading 6.11 Model Questions 6.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you will be able to- know about the religious traditions in Assam and its historical past, discuss Saivism and its influence in Assam, discuss Saktism as a faith practised in Assam, describe the spread and impact on Buddhism on the general life of the people, Cultural History of Assam 95 Unit 6 Assamese Culture: Syncretism and Assimilation 6.2 INTRODUCTION Religion has a close relation with human life and man’s life-style. From the early period of human history, natural phenomena have always aroused our fear, curiosity, questions and a sense of enquiry among people. In the previous unit we have deliberated on the rich folk culture of Assam and its various aspects that have enriched the region. We have discussed the oral traditions, oral literature and the customs that have contributed to the Assamese culture and society. In this unit, we shall now discuss the religious traditions of Assam.