Transistor Circuit Techniques: Discrete and Integrated, Third Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transistor Circuit Guidebook Byron Wels TAB BOOKSBLUE RIDGE SUMMIT, PA

TAB BOOKS No. 470 34.95 By Byron Wels TransistorCircuit GuidebookByronWels TABBLUE RIDGE BOOKS SUMMIT,PA. 17214 Preface beforemeIa supposepioneer (along the my withintransistor firstthe many field.experiencewith wasother Weknown. World were using WarUnlike solid-stateIIsolid-state GIs) today's asdevices somewhat experimen- receivers marks of FIRST EDITION devicester,ownFirst, withsemiconductors! youwith a choice swipedwhichor tank. ofto a sealed,Here'sexperiment, pairThen ofhow encapsulated, you earphones we carefullywe did had it: from totookand construct the veryonenearest exoticof our the THIRDSECONDFIRST PRINTING-SEPTEMBER PRINTING-AUGUST PRINTING-JANUARY 1972 1970 1968 plane,wasyouAnphonesantenna. emptywound strung jeep,apart After toiletfull outand ofclippingas paper wire,unwoundhigh closelyrollandthe servedascatchthe far spaced.wire offas as itfrom a thewouldsafetyThe thecoil remaining-pin,magnetreach-for form, you inside.which stuckwire the Copyright © 1968by TAB BOOKS coatedNext,it into youneeded,a hunkribbons of -ofwooda razor -steel, soblade.the but point Oh,aItblued was noneprojected placedblade of the -quenchat so fancy right the pointplastic-bluedangles.of -, Reproduction or publicationPrinted inof the ofAmerica the United content States in any manner, with- themindfoundphoneground pin you,the was couldserved right not wired contact lacquerspotas toa onground blade, it. theblued.blade'sAconnector, pin,bayonet bluing,and stuck antennaand you hilt thecould coil.-deep other actuallyIfin ear- youthe isoutherein. assumed express -

Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers

Chapter 7: Transistors, part 2 Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers The transistor amplifiers that we studied in the last chapter have some serious problems for use in AC signals. Their most serious shortcoming is that there is a “dead region” where small signals do not turn on the transistor. So, if your signal is smaller than 0.6 V, or if it is negative, the transistor does not conduct and the amplifier does not work. Design goals for an AC amplifier Before moving on to making a better AC amplifier, let’s define some useful terms. We define the output range to be the range of possible output voltages. We refer to the maximum and minimum output voltages as the rail voltages and the output swing is the difference between the rail voltages. The input range is the range of input voltages that produce outputs which are not at either rail voltage. Our goal in designing an AC amplifier is to get an input range and output range which is symmetric around zero and ensure that there is not a dead region. To do this we need make sure that the transistor is in conduction for all of our input range. How does this work? We do it by adding an offset voltage to the input to make sure the voltage presented to the transistor’s base with no input signal, the resting or quiescent voltage , is well above ground. In lab 6, the function generator provided the offset, in this chapter we will show how to design an amplifier which provides its own offset. -

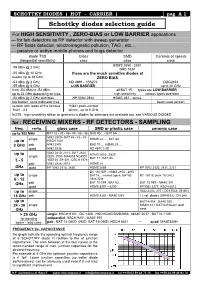

Schottky Diodes Selection Guide

SCHOTTKY DIODES ( HOT - CARRIER ) pag A 1 Schottky diodes selection guide For HIGH SENSITIVITY , ZERO-BIAS or LOW BARRIER applications --- for lab detectors as RF detector with sweep generator --- RF fields detector, electromagnetic pollution, TAG , etc… --- passive or active mobile phones and bugs detector diode TSS Glass SMD Ceramic or special (tangential sensitivity) case case case HSMS 2850 - 2851 -59 dBm @ 2 GHz SMS 7630 -55 dBm @ 10 GHz these are the much sensitive diodes at usable up to 18 GHz ZERO BIAS -53 dBm @ 2 GHz ND 4991 - 1SS276 DDC2353 -55 dBm @ 6 GHz LOW BARRIER up to 20 GHz from -54 dBm to -52 dBm all BAT 15… types are LOW BARRIER up to 24 GHz depending on type high sensitivity vatious types available -56 dBm @ 2 GHz with bias HP 5082-2824 HSMS.282…series low barrier, up to millimeter freq. beam lead version version with leads of the famous 1N821 point-contact 1N21 - 23 silicon , up to 5 GHz NOTE : high sensitivity silicon or germanium diodes for detectors are available too, see VARIOUS DIODES for : RECEIVING MIXERS - RF DETECTORS - SAMPLING freq. config. glass case SMD or plastic case ceramic case up to 500 MHz BAT 42 - 43 - 46 - 48 - 85 - 86 BAS 40-…- BAT 64-.... 5082.2800 - BAT 45 - 82 - 83 single HSMS 28.... , BAT 68 up to HSCH 1001 2 GHz pair 5082.2804 BAS 70... , HSMS 28... quad 5082.2836 ND 487C1-3R 5082.2810, 2811, 2817 2824, up to HSMS 2810 , 2820 single 2835, 2900, MA4853 ND4991 BAT 17 , BAT 68 3 - 5 1SS154 ,BA 481, QSCH 5374 pair 5082.2826, 2912 HSMS 28…. -

Special Diodes 2113

CHAPTER54 Learning Objectives ➣ Zener Diode SPECIAL ➣ Voltage Regulation ➣ Zener Diode as Peak Clipper DIODES ➣ Meter Protection ➣ Zener Diode as a Reference Element ➣ Tunneling Effect ➣ Tunnel Diode ➣ Tunnel Diode Oscillator ➣ Varactor Diode ➣ PIN Diode ➣ Schottky Diode ➣ Step Recovery Diode ➣ Gunn Diode ➣ IMPATT Diode Ç A major application for zener diodes is voltage regulation in dc power supplies. Zener diode maintains a nearly constant dc voltage under the proper operating conditions. 2112 Electrical Technology 54.1. Zener Diode It is a reverse-biased heavily-doped silicon (or germanium) P-N junction diode which is oper- ated in the breakdown region where current is limited by both external resistance and power dissipa- tion of the diode. Silicon is perferred to Ge because of its higher temperature and current capability. As seen from Art. 52.3, when a diode breaks down, both Zener and avalanche effects are present although usually one or the other predominates depending on the value of reverse voltage. At reverse voltages less than 6 V, Zener effect predominates whereas above 6 V, avalanche effect is predomi- nant. Strictly speaking, the first one should be called Zener diode and the second one as avalanche diode but the general practice is to call both types as Zener diodes. Zener breakdown occurs due to breaking of covalent bonds by the strong electric field set up in the depletion region by the reverse voltage. It produces an extremely large number of electrons and holes which constitute the reverse saturation current (now called Zener current, Iz) whose value is limited only by the external resistance in the circuit. -

Electronic Circuit Design and Component Selecjon

Electronic circuit design and component selec2on Nan-Wei Gong MIT Media Lab MAS.S63: Design for DIY Manufacturing Goal for today’s lecture • How to pick up components for your project • Rule of thumb for PCB design • SuggesMons for PCB layout and manufacturing • Soldering and de-soldering basics • Small - medium quanMty electronics project producMon • Homework : Design a PCB for your project with a BOM (bill of materials) and esMmate the cost for making 10 | 50 |100 (PCB manufacturing + assembly + components) Design Process Component Test Circuit Selec2on PCB Design Component PCB Placement Manufacturing Design Process Module Test Circuit Selec2on PCB Design Component PCB Placement Manufacturing Design Process • Test circuit – bread boarding/ buy development tools (breakout boards) / simulaon • Component Selecon– spec / size / availability (inventory! Need 10% more parts for pick and place machine) • PCB Design– power/ground, signal traces, trace width, test points / extra via, pads / mount holes, big before small • PCB Manufacturing – price-Mme trade-off/ • Place Components – first step (check power/ground) -- work flow Test Circuit Construc2on Breadboard + through hole components + Breakout boards Breakout boards, surcoards + hookup wires Surcoard : surface-mount to through hole Dual in-line (DIP) packaging hap://www.beldynsys.com/cc521.htm Source : hap://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Breadboard_counter.jpg Development Boards – good reference for circuit design and component selec2on SomeMmes, it can be cheaper to pair your design with a development -

Integrated Circuits

CHAPTER67 Learning Objectives ➣ What is an Integrated Circuit ? ➣ Advantages of ICs INTEGRATED ➣ Drawbacks of ICs ➣ Scale of Integration CIRCUITS ➣ Classification of ICs by Structure ➣ Comparison between Different ICs ➣ Classification of ICs by Function ➣ Linear Integrated Circuits (LICs) ➣ Manufacturer’s Designation of LICs ➣ Digital Integrated Circuits ➣ IC Terminology ➣ Semiconductors Used in Fabrication of ICs and Devices ➣ How ICs are Made? ➣ Material Preparation ➣ Crystal Growing and Wafer Preparation ➣ Wafer Fabrication ➣ Oxidation ➣ Etching ➣ Diffusion ➣ Ion Implantation ➣ Photomask Generation ➣ Photolithography ➣ Epitaxy Jack Kilby would justly be considered one of ➣ Metallization and Intercon- the greatest electrical engineers of all time nections for one invention; the monolithic integrated ➣ Testing, Bonding and circuit, or microchip. He went on to develop Packaging the first industrial, commercial and military ➣ Semiconductor Devices and applications for this integrated circuits- Integrated Circuit Formation including the first pocket calculator ➣ Popular Applications of ICs (pocketronic) and computer that used them 2472 Electrical Technology 67.1. Introduction Electronic circuitry has undergone tremendous changes since the invention of a triode by Lee De Forest in 1907. In those days, the active components (like triode) and passive components (like resistors, inductors and capacitors etc.) of the circuits were separate and distinct units connected by soldered leads. With the invention of the transistor in 1948 by W.H. Brattain and I. Bardeen, the electronic circuits became considerably reduced in size. It was due to the fact that a transistor was not only cheaper, more reliable and less power consuming but was also much smaller in size than an electron tube. To take advantage of small transistor size, the passive components too were greatly reduced in size thereby making the entire circuit very small. -

35402 Electronic Circuit R TG

Electricity and Electronics Electronic Circuit Repair Introduction The purpose of this video is to help you quickly learn the most common methods used to trou- bleshoot electronic circuits. Electronic troubleshooting skills are needed to diagnose and repair several types of devices. These devices include stereos, cameras, VCRs, and much more. As mentioned, the program will explain how to diagnose and repair different types of electronic com- ponents and circuits. Viewers will also learn how to use the specialized tools and instruments needed to test these particular types of circuits and components. If students plan to enter any type of electronics field, viewing this program will prove to be beneficial. The program is organized into major sections or topics. Each section covers one major segment of the subject. Graphic breaks are given between each section so that you can stop the video for class discussion, demonstrations, to answer questions, or to ask questions. This allows you to watch only a portion of the program each day, or to present it in its entirety. This program is part of the ten-part series Electricity and Electronics, which includes the following titles: • Electrical Principles • Electrical Circuits: Ohm's Law • Electrical Components Part I: Resistors/Batteries/Switches • Electrical Components Part II: Capacitors/Fuses/Flashers/Coils • Electrical Components Part III: Transformers/Relays/Motors • Electronic Components Part I: Semiconductors/Transistors/Diodes • Electronic Components Part II: Operation—Transistors/Diodes • Electronic Components Part III: Thyristors/Piezo Crystals/Solar Cells/Fiber Optics • Electrical Troubleshooting • Electronic Circuit Repair To order additional titles please see Additional Resources at www.filmsmediagroup.com at the end of this guide. -

Basic DC Motor Circuits

Basic DC Motor Circuits Living with the Lab Gerald Recktenwald Portland State University [email protected] DC Motor Learning Objectives • Explain the role of a snubber diode • Describe how PWM controls DC motor speed • Implement a transistor circuit and Arduino program for PWM control of the DC motor • Use a potentiometer as input to a program that controls fan speed LWTL: DC Motor 2 What is a snubber diode and why should I care? Simplest DC Motor Circuit Connect the motor to a DC power supply Switch open Switch closed +5V +5V I LWTL: DC Motor 4 Current continues after switch is opened Opening the switch does not immediately stop current in the motor windings. +5V – Inductive behavior of the I motor causes current to + continue to flow when the switch is opened suddenly. Charge builds up on what was the negative terminal of the motor. LWTL: DC Motor 5 Reverse current Charge build-up can cause damage +5V Reverse current surge – through the voltage supply I + Arc across the switch and discharge to ground LWTL: DC Motor 6 Motor Model Simple model of a DC motor: ❖ Windings have inductance and resistance ❖ Inductor stores electrical energy in the windings ❖ We need to provide a way to safely dissipate electrical energy when the switch is opened +5V +5V I LWTL: DC Motor 7 Flyback diode or snubber diode Adding a diode in parallel with the motor provides a path for dissipation of stored energy when the switch is opened +5V – The flyback diode allows charge to dissipate + without arcing across the switch, or without flowing back to ground through the +5V voltage supply. -

Full-Wave Electromagnetic Modeling of Electronic Device Parasitics for Terahertz Applications

Full-wave Electromagnetic Modeling of Electronic Device Parasitics for Terahertz Applications Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yasir Karisan, B.S., M.S. Graduate Program in Electrical and Computer Engineering The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Kubilay Sertel, Advisor Patrick Roblin Fernando L. Teixeira Gary Kennedy c Copyright by Yasir Karisan 2015 Abstract The unique spectroscopic utility and high spatial resolution of terahertz (THz) waves offer a new and vastly unexplored paradigm for novel sensing, imaging, and communication applications, varying from deep-space spectroscopy to security screen- ing, from biomedical imaging to remote non-destructive inspection, and from ma- terial characterization to multi-gigabit wireless indoor and outdoor communication networks. To date, the THz frequency range, lying between microwave and in- frared bands, has been the last underexploited part of the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum due to technical and economical limitations of classical electronics- and optics-based system implementations. However, thanks to recent advancements in nano-fabrication and epitaxial growth techniques, sources and sensors with cutoff frequencies reaching the submillimeter-wave (sub-mmW) band are now realizable. Such remarkable improvement in electronic device speeds has been achieved mainly through aggressive scaling of critical device features, such as the junction area for Schottky barrier diodes (SBDs), and the gate length in high electron mobility tran- sistors (HEMTs). Such aggressively-scaled and refined device topologies can signif- icantly enhance the intrinsic device capabilities, however, the overall device perfor- mance is still limited by the parasitic couplings associated with device interconnect metallization. -

Chapter 3: the MOS Transistor (Pdf)

chapter3.fm Page 43 Monday, September 6, 1999 1:50 PM CHAPTER 3 THE DEVICES Qualitative understanding of MOS devices n Simple component models for manual analysis n Detailed component models for SPICE n Impact of process variations 3.1 Introduction 3.3.3 Dynamic Behavior 3.2 The Diode 3.3.4 The Actual MOS Transistor—Some Secondary Effects 3.2.1 A First Glance at the Diode — The 3.3.5 SPICE Models for the MOS Transistor Depletion Region 3.2.2 Static Behavior 3.4 A Word on Process Variations 3.2.3 Dynamic, or Transient, Behavior 3.5 Perspective: Technology Scaling 3.2.4 The Actual Diode—Secondary Effects 3.2.5 The SPICE Diode Model 3.3 The MOS(FET) Transistor 3.3.1 A First Glance at the Device 3.3.2 The MOS Transistor under Static Conditions 43 chapter3.fm Page 44 Monday, September 6, 1999 1:50 PM 44 THE DEVICES Chapter 3 3.1Introduction It is a well-known premise in engineering that the conception of a complex construction without a prior understanding of the underlying building blocks is a sure road to failure. This surely holds for digital circuit design as well. The basic building blocks in today’s digital circuits are the silicon semiconductor devices, more specifically the MOS transis- tors and to a lesser degree the parasitic diodes, and the interconnect wires. The role of the semiconductor devices has been appreciated for a long time in the world of digital inte- grated circuits. On the other hand, interconnect wires have only recently started to play a dominant role as a result of the advanced scaling of the semiconductor technology. -

(Or Varicap) Diode

Radio and Electronics Cookbook 20 The varactor (or varicap) diode Introduction Many of the circuits for receivers and transmitters presented in this series rely upon the variable capacitor as a means of tuning. Another method of varying capacitance (without any moving parts) is provided by the varactor diode, sometimes called a varicap diode. This is a component which changes its capacitance as the voltage across it is varied. The details Figure 1 shows how a varactor diode might be connected to demonstrate its operation. Its symbol is that of an ordinary diode, with a capacitor symbol next to it. A variable voltage is applied across it in such a way that the diode is reverse-biased. This means that virtually no current passes through it – the positive voltage is applied to the cathode. Varactors are cheaper than variable capacitors, and they are tiny in comparison, very suitable for today’s miniature circuits. If A and B were connected across the tuning coil in a simple receiver (with a series capacitor to block the DC from the battery reaching the coil), the tuning operation would be accomplished by turning the knob on the 10 kilohm potentiometer. Varactors are available with different values, from less than 20 picofarad (pF) for VHF applications to 500 pF for medium-wave radios. They are Figure 1 The capacitance of the varicap diode (between A and B) increases as the voltage is reduced, using the variable resistor 64 A portable radio for medium waves tuned usually by voltages between 2 V and 9 V. For a real application of varactors, you should consult the circuit diagram of the Yearling 20 metre receiver, elsewhere in this book. -

J. W. Miller Company the Coil Forum March 1960

J. W. MILLER COMPANY-LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA-VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1 MARCH 1960 A TRANSISTOR FM RECEIVER With this issue, the J. W. Miller Company inaugurates a new publication devoted to the experimenter. Although coils, and their associated com ponents, are our business, we at Miller would like to supply our customers with timely information on circuits, theory to assist with your work or experiments, and data on how to select and use our coils wisely. We believe you will agree that THE COIL FORUM is indeed an appropriate nam~. www.SteamPoweredRadio.Com J. W. M I L L E R C O M P A N Y Recent advances in the state of the semiconductor from the collector back to the base through capacitor art have made it possible to construct a transistor Cl2 and the stage oscillates. Coil L3, along with the FM receiver which performs every bit as well as a tuning capacitor and circuit capacity, determines the vacuum tube version. VHF equipment places very frequency of oscillation, which is always 10. 7 me. strict demands on the transistors. They must be above the incoming signal frequency. Resistors R9 capable of constant amplification over the entire and Rl 1 provide bias and RIO is used for d.c. degener band being received, create a minimum of circuit ation. Transistor QlO and diode Xl are part of the drift, and provide maximum gain with a minimum automatic frequency control system and will be of stages. ' discussed later. All tuned circuits in the "front end" are tracked with a three-gang variable capacitor The excellent performance of the receiver to be (C3, 3-lOmmfd.) described is an outgrowth of the work done by Philco Corporation on their transistor "Safari" tele The i.f.